The day before Super Bowl LVIII, as I made my way to Las Vegas’s Mandalay Bay Convention Center for the “Super Bowl Experience,” a Toyota-sponsored sprawl of activities and exhibitions celebrating professional football, I was pleased to have finally encountered an intersection where pedestrians might conceivably cross the street. Along the Las Vegas Strip, I’d discovered, there are not so much intersections as there are walkways, erected some forty feet off the ground, over which one crosses not simply to the other side of the street but most often into a hotel or shopping center, inside of which an escalator might deposit you into a room of slot machines.

But here, where Mandalay Bay Road met Las Vegas Boulevard, and just steps from Harry Reid International Airport, was a crosswalk, where a group of men wearing cowboy hats and lily-white pants splattered with red paint was demonstrating against male circumcision. (“STOP CUTTING BABY PENIS,” one sign read. “I WANT MY FORESKIN BACK,” said another.) At last, I’d reached the end of an odyssey that had started at my hotel some four and a half miles north. Somewhere along the way, I’d asked to interview a pair of feathered showgirls who demanded $60 in return.

Once I’d crossed six lanes of traffic, offering the demonstrators the kind of ambivalent head nod that I hoped would leave the matter of my own foreskin unresolved, I met Jesse and Phyllis, two San Francisco 49ers fans, married and retired, who assured me that special teams—the third unit, after offense and defense, comprised of kickers, punters, long snappers, and return men—would decide the big game. If the Niners win, Jesse added, without elaboration, he’d go back to his old job selling baby clothes outside of abortion clinics. Then, as if to demonstrate the depths of his devotion, he pulled out a photo of himself at Candlestick Park on January 10, 1982, the day Joe Montana, rolling right, with three Dallas Cowboys defenders in his face, heaved the football up for Dwight Clark in the back of the endzone. This moment has since become known, in the triumphalist parlance of the NFL, as “The Catch.”

Inside the “Super Bowl Experience,” for which tickets cost $25 on Wednesday and $50 over the weekend, there was a similar sense of hagiography, of the NFL leveraging its glorious mythology as it charges headlong into an ever-more-profitable future. In the long line to see the Vince Lombardi Trophy—encased in glass and secured by a lady holding a hand towel and a bottle of Windex—a young boy, no more than ten years old, instructed his father in a call-and-response chant of the 49ers fight song. Nearby, a multigenerational group of Kansas City Chiefs fans, all wearing jerseys that read “BESTIES” in place of a player’s last name, appeared to be conducting a sort of rallying cry of their own for a local television crew.

Fans of the pitiable Las Vegas Raiders, merely content to be hosting a Super Bowl for the first time, showed up in droves, as did supporters of seemingly every franchise in the league whose season had already concluded. They wore jerseys, of course, but also NFL-branded beads and beanies and socks and tote bags and varsity jackets. Briefly, I lamented that I could not join them. My Baltimore Ravens jersey was sitting at the bottom of a laundry basket in my apartment in New York, where I had placed it, streaked with Coors Light, after we lost to the Kansas City Chiefs in the AFC Championship game two weeks earlier.

You see, my team, which was the best in the league this season by most measurable statistics, should have been here. It was supposed to be our year. So sure was I in this conviction that I’d returned home to Baltimore for the game, bought nosebleeds and a train ticket and a pair of purple camouflage pants, then texted everyone whose name I still remembered from high school to organize a tailgate in the stadium parking lot, where we could drink beer and smoke cigars together in expectation of our first Super Bowl berth in ten years.

I’d been struggling to get over the loss. Even friends who find my obsession with football strange and unseemly sent their condolences, to which I did not reply. But minutes after entering the “Super Bowl Experience,” I noticed a young boy, smiling wide, scaling the headless, life-sized figure of a Ravens player for a face-in-the-hole photo op. He would not have been alive the last time we won the Super Bowl, in 2013, and had never known that pinnacle of sports fandom. But nor had his enthusiasm been dulled by the methodical and exhaustive year-to-year toil of being a fan, the crushing sense, which I was still trying to forestall, that all this time and attention had led only to disappointment.

Advertisement

I resolved to be a better sport and braved the line for the forty-yard dash, where parents passed their phones and wallets off to staffers and stretched out their hamstrings to compete against their children. This was just one of several attractions offering fans who scanned a barcode and downloaded an app the chance to partake in something resembling organized football. There were also the two-minute drill, the QB scramble, the obstacle course, the extra point kick, the FedEx Air Challenge, the FedEx Ground Challenge, and a full-fledged eleven-on-eleven flag football game in which a rotation of dutiful adult volunteers played quarterback, imposing order on an unruly squad of child receivers. There was a pickleball court, too, for no better observable reason than that the convention center had 700,000 square feet of space to fill.

But the “Super Bowl Experience” is not just about wholesome fun or family bonding or children cosplaying as football players. It is also about corporate sponsors and the NFL’s pursuit of interminable, international growth. Over the last decade, the league has brought regular season football to Frankfurt, London, Munich, and Mexico City, and in 2024 a game will be played in São Paulo. The NFL seems to have big plans for China, too, having recently awarded marketing rights in the country to the Los Angeles Rams. Appropriately, then, there was a twenty-foot-long paper dragon being paraded around the convention center by a small cavalry of volunteers to mark the Chinese Lunar New Year. Elsewhere on the grounds, you could sign up for a new Visa credit card with your team’s logo on it, or “test your grip strength” with the health insurance giant Cigna, or “pick your starting wineup” with Barefoot Wines, or throw a football through the “O” in the Lowe’s hardware logo, or watch your child throw themselves into a ball pit of Toyota-red nerf footballs. In this windowless football theme park that bore all the sensory trappings of a casino, you could imagine why the NFL has finally brought the Super Bowl to Vegas.

*

Among the things one could bet on at this year’s Super Bowl: the color of the Gatorade dumped on the winning team’s coach; the number of times the telecast would show Taylor Swift; whether or not Travis Kelce would propose to her; the song with which Usher would open the halftime Show; whether Ludacris would feature in it; whether a field goal attempt would hit the upright and/or crossbar; who would win the opening coin toss; whether any one scoring drive would be shorter than Reba McIntire’s rendition of the national anthem; and if that rendition would bring any players to tears. And these were just the novelty props, offered on any number of unregulated offshore betting sites, though they made for cheerful conversation on ESPN’s hours-long pregame telecast.

Until recently, the NFL was precious about commingling with Vegas. In 1992 President George H. W. Bush signed the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA) into law, effectively banning sports betting outside Nevada. Testifying for the bill’s passage before Congress, then–NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue made a full-throated appeal to the league’s upstanding “character,” fearing that, in a world of legalized sports gambling, pro football was becoming synonymous with “the fast buck, the quick fix, the desire to get something for nothing.”

Any association with Vegas ran counter to these pieties: in 2003 the NFL prohibited Super Bowl telecasts from airing an ad spot with the slogan “What Happens Here, Stays Here,” devised by a local ad agency that was looking to lean into the city’s reputation as an adults-only playground. Ten years later, in a declaration opposing the state of New Jersey’s attempts to overturn PASPA, the current NFL commissioner, Roger Goodell, echoed his predecessor’s concerns, warning of “the harm sports gambling poses to the goodwill, character and integrity of NFL football and to the fundamental bonds of loyalty and devotion between fans and team.”

The league was historically punitive toward its own, too. In 1963 it suspended two superstars—the Packers’ Paul Hornung and the Lions’ Alex Karras—for the entire season for wagering on football. More recently, in the gray market days of 2015, even former Dallas Cowboys quarterback Tony Romo, now the lead color analyst for CBS Football, was banned from hosting a fantasy football convention at the Venetian.

But when the Supreme Court overturned PASPA in 2018, the NFL made an about-face and embraced the fresh revenue streams that emerged from the ensuing explosion of online gambling—to the tune of an estimated $2.3 billion a year. On DraftKings, FanDuel, Caesars, WynnBET, BetMGM, and PointsBet—just six of the sportsbooks with which the NFL has signed official partnerships since the Supreme Court decision—the sport is gamified down to its rudiments, with few if any possibilities unaccounted for. This year, you won big if you bet on the game going into overtime (at 11:1 odds), and even bigger if you thought a player other than a quarterback would throw a touchdown pass (at 35:1). The morning after the game, the Nevada Gaming Control Board reported $185 million in wagers for Super Bowl LVIII, up $32 million from last year’s game, while FanDuel announced a total handle of $307 million, a 40 percent increase from 2023. BetMGM, meanwhile, saw a 51 percent increase in female bettors, an uptick most reports enthusiastically attributed to Swift, who, as it turned out, was not proposed to (and was only shown on screen for a total of fifty-four seconds, far less than what was feared by those who suspected her appearance was an elaborate plot by the Biden administration, but far more than the betting line—28.5 seconds).

Advertisement

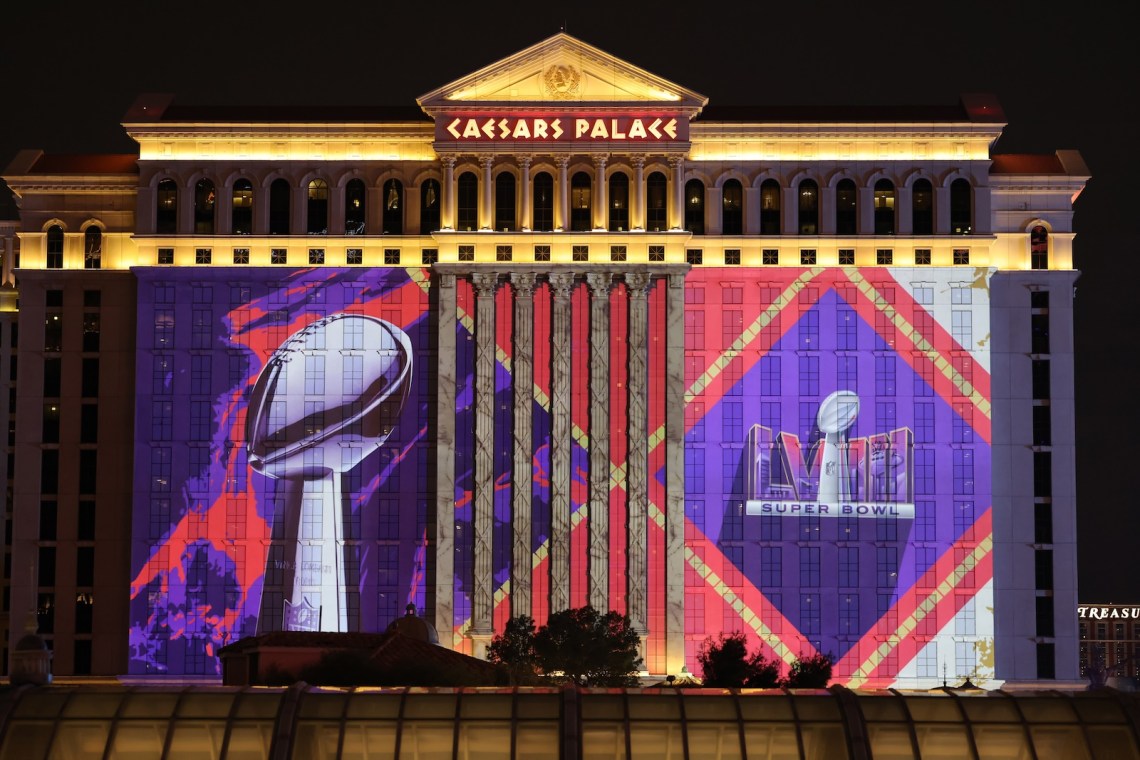

The Super Bowl in Vegas was as obvious a marriage as it was verboten. As early as 2017 the league had been priming fans for its Sin City immersion, first by relocating the Oakland Raiders to Las Vegas, and then by granting the city host duties for the 2022 NFL Draft and the 2022 Pro Bowl, which was held in the brand-new, jet-black $1.9 billion Allegiant Stadium (located just off the Strip and funded in part publicly, as most NFL stadiums are). Over Super Bowl weekend, the locals I talked to seemed to regard the league’s imprimatur with a kind of polite indifference. Construction was extravagant, they said, and it took longer to drive to work. But the NFL’s citywide siege was exciting.

The morning of the game, while crushing a bushel of mint leaves for the super-sized frozen mojitos that a group of Niners fans had ordered at the Purple Zebra Daiquiri Bar, Eric Douglas noted how much had changed since he began bartending in the city forty years ago. “What I loved about Vegas was the simplicity of the town,” he said. “When I first moved here, there wasn’t even a West Side.” Now, he added, “it’s becoming a lot like Los Angeles,” though he was looking forward to the recently approved relocation of the MLB’s Oakland Athletics to Vegas. It appears likely that an NBA expansion franchise will soon come to town, too. “Everything makes its way to Vegas at some point,” said Amber Barkley, a Nevada native. “We’re a sports city now.”

*

I was silly enough to think that, on what would be the single most profitable day of the year for Vegas sportsbooks, I could arrive at Circa Resort & Casino three and a half hours before kickoff and still get a seat in the hotel’s sportsbook, which became the city’s largest by a considerable margin when it opened in 2020. It takes up three stories and holds a thousand people, 350 of whom can reserve reclining seats in the “stadium,” in front of which looms a thirty-eight-foot-tall, 118-foot-wide, 78-million-pixel video screen, itself comprising more than a dozen smaller screens set to hockey, soccer, college basketball, and various Super Bowl pregame telecasts. These screens are flanked, on the left and right, by a constantly updating odds board and a running stream of the @CircaSports Twitter feed, which at 12:47 Pacific Time the day of the big game was sharing news about the Philadelphia Phillies’ acquisition of a once highly touted but now mediocre pitcher. A hostess told me that the three remaining single seats in the stadium were going for $400 each. I elected to stand.

Just beneath the electronic odds board is the Sports Gambling Hall of Fame, whose inaugural class had been fêted with a black-tie ceremony at Circa the summer before. Now, their names and specific contributions are inscribed on gold plaques. There was, of course, one for Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal, the Vegas kingpin immortalized by Robert De Niro in Martin Scorsese’s Casino. But the names of lesser-known people who were crucial to the expansion of the gambling industry were listed, too, like Billy Walters (“known for being the greatest sports bettor of all time,” read his plaque, and “contributing as a philanthropist to many causes”) and Jack Franzi (“he knew the value of credible information & how to maximize that information”).

The whole operation made the New York Stock Exchange look woefully old-fashioned. And there, at least to my knowledge, you can’t smoke cigarettes or eat chicken wings or hock a loogie right onto the carpet with impunity, as I witnessed a man carrying an oxygen tank and wearing a Nick Bosa jersey do twice. Most people, though, were lined up at one of several kiosks waiting to place their bets, or otherwise studiously analyzing the seven-page, double-sided packet of betting lines and game props, printed on legal paper and strewn around the premises. Prop packets, though slightly less extensive, were also available for the 2024 Kentucky Derby, in three months’ time, and a women’s tennis event taking place in Qatar later that week. I had planned to put down a parlay: two touchdowns for Christian McCaffrey, plus the over on George Kittle receiving yards, plus the under on Patrick Mahomes rushing yards. (In order to win on such a bet, all three events must happen, which makes parlays catnip for the fan who prefers his attention and loyalties manically divided.) But—fortunately, it turns out, since none of them happened—I did not have the patience or wherewithal to wager at the sportsbook, where lines were long and online betting sites like FanDuel and DraftKings are forbidden. Circa Sportsbook was not for casual gamblers like me, the ones who’d only begun wagering when the reversal on the federal ban allowed us to do so from our phones, on handsome, user-friendly apps with easily navigable interfaces. This was for old hands and high rollers, the kind of people who’d reserved their “stadium” seats months in advance.

It was easy to tell who those people were. Hours before kickoff, they were already seated comfortably in leather recliners, marking up their packets with number two pencils as each television gradually changed over to CBS, turning the 78-million-pixel video screen into a giant mosaic of fresh green grass. They did not announce their loyalties with anything as gauche as a football jersey. They worshiped instead at the altar of statistics and good luck.

Renee, sitting in a stadium seat beside his wife, told me he’d been betting on football for thirty-five years. “All of my adulthood, we didn’t have legalized gambling much in Texas, so we had to come to other places,” he said. “You know, some men do things for adrenaline, climb mountains or race cars, and I do this.” It would not be long, he predicted, before Las Vegas entered the rotation of regular Super Bowl host cities alongside Miami and New Orleans. “The NFL…dictates everything, if you really look at it,” he explained. “What shows on TV, when you watch, what you watch, what time things are open.” He did not offer much in the way of gambling strategy except to say that “Vegas doesn’t get it wrong.” Indeed, the total points line for Super Bowl LVIII had been set at 47.5. The Chiefs won 25–22, much to the chagrin of those who had bet the over.

*

It was, on the whole, an engaging game, at first for those who appreciate the pleasant swarm of a well-coached defense and, later, for fans of quick, high-pressure scoring. But it began nervously, with two fumbles in the first quarter halting long, would-be touchdown drives for either team. Scoring was low and tensions were high. Travis Kelce, angry at having been taken off the field during an early push into Niners territory, grabbed the arm of Chiefs head coach Andy Reid, nearly knocking the sixty-five-year-old over. Niners linebacker Dre Greenlaw was loaded onto the injury cart after freakishly tearing his Achilles tendon while jogging onto the field. One couldn’t help but speculate on the quality of the grass, imported from a sod farm in California, that had been rolled up, shipped, moisturized, rolled out again, and finally installed in Allegiant Stadium, only to be covered over in a tarp and trampled by rehearsals for the halftime show.

Niners placekicker Jake Moody drilled a fifty-five-yard field goal. Christian McCaffrey scored a touchdown, which was all but certain: a $10 wager on it would only have yielded you $4.26. And Mahomes, lying in wait, orchestrated a game-winning drive in overtime, having hung around long enough for the tired and outwitted Niners to yield to the seeming inevitability that he and his offense would eventually start to gel.

To watch all of this transpire at Circa Sportsbook was to see vast sums of money changing hands in real time. The outcome suddenly meant as much to someone like Renee as it did to the die-hard Niners and Chiefs fans who watched in alternating states of rapture and disbelief. But did it, really? The stakes, in some cases, had been manufactured, such that you might find yourself hoping for both teams to score, if you took the over on total points, or neither, or one in the first quarter and the other in the fourth. Slumped at the one slot machine I’d found with an unobstructed view of the main screen, it was easy to see the games within the games, all the various modes of investment football could engage at once. That I found one more sacred than the others was entirely beside the point; the NFL enjoyed the spoils regardless.

The league is bigger than ever, entering a sort of imperial era in which its gestures to family and capital, to progressivism and traditional values, to Nickelodeon and Ancient Rome, all sit side-by-side. The NFL logo, a red, white, and blue shield, was an apt metaphor for its seeming immunity to prevailing national currents of institutional distrust. Here was the world’s biggest sports league, with its arsenal of controversies and contradictions, holding us captive once again, turning the Super Bowl into event television for factions as dissimilar as football freaks, sport agnostics, gambling addicts, Swifties, data analysts, beer enthusiasts, advertising agents, and anyone who suspected Beyoncé might leverage the occasion to announce a new album.

That the NFL was peaking now struck me as somewhat improbable, since at various points in my football-watching life the league had seemed to be in decline, reeling from wounds both external and self-inflicted. There was the tyranny of its ownership class, a group of mostly octogenarian billionaires whose politics of self-enrichment were increasingly transparent, and the mutiny of its players, who are now, at the behest of a new collective bargaining agreement, playing more games than ever but are still expected not to pass judgment on league officiating or political affairs. And there was, of course, the matter of traumatic brain injuries, which we know incontrovertibly to be a consequence of playing football. Parents are signing their kids up to play in high school and middle school at far lower rates. Former players suffer in private and pledge to donate their brains to science—or they fight the league for just medical compensation and are met with denial and, later, brigades of lawyers. As all this became common knowledge, the notion took hold that football was in danger and that we, the viewing public, were increasingly complicit in the damages it had wrought.

But 123.4 million of us, to be exact, watched the Super Bowl, the largest audience for an American television event since the moon landing. And I personally had watched more football this season than ever: every game involving my own team and then, I’d estimate, another two or three each week. Of course, not all of them held equal weight. Some took a real psychic toll, while others were merely an opportunity to turn $10 into a couple hundred, provided various things took place, concurrently, exactly as I’d hoped. And others still I’d watched passively, lulled into a fugue by the immersive choreography of the game and the familiar rhythms of its high-def presentation. The spiritual and economic arrangements binding us to football are not unlike those that might compel someone to go to Las Vegas, that most improvident of American cities, where luck pervades the air and consequence is kept out of sight.

The 2023 NFL season was officially over, but Chiefs and Niners fans were onto the next game, shrouding the slot machines and craps tables in a sea of their respective reds. Awaiting me in my hotel room was the Vince Lombardi Trophy, rendered in milk chocolate and plated with other shiny, football-themed chocolates, the kind of on-theme parting gift that may or may not be typical of Vegas hotels hosting visiting sports writers. It was small enough to hold, or even hoist victoriously, but far too big to actually eat, so it sat there like a curio or a poker chip, luring me already with the prospect of another season, another hand.