The painter Charles Burchfield kept a journal for most of his life, from 1909, when he was sixteen, to 1966, a year before his death. He filled some ten thousand pages—seventy-two notebooks containing an assortment of newspaper clippings, sketches, doodles, and notations alongside written reflections on his daily life and the natural world. Still, looking back over the dozens of journals in December 1966, he felt that painting was his primary mode of expression: “I would say that one good picture is worth more than all the journals put together.”

Burchfield is best known for his ecstatic watercolors of intimate landscapes—“an unrepentant, gnostic vision,” as the critic Dave Hickey once put it—inspired by his surroundings in rural Ohio and Erie County, New York, near Buffalo. His paintings most frequently depict nature: all kinds of weather, times of day, and seasons; local flora and bird life; and the inexhaustible variation of the sky. “There is nothing in nature that will ever fail to interest me,” he wrote in his journal on March 25, 1911, the first entry in The Sphinx and the Milky Way, a selection of Burchfield’s journals edited by the poet Ben Estes and introduced by the preeminent Burchfield scholar Nancy Weekly.1

Burchfield may have prioritized visual expression, but writing ran in tandem to his artmaking. In 1943, he began reworking and enlarging certain earlier paintings. Around the central watercolor, he added strips of paper, beveling the edges so that the different sections fit together seamlessly, which allowed him to expand the original scene to express a more transcendental vista. In an interview in 1959, he explained this process in writerly terms:

I like to be able to advance and retreat just like a man writing a book. I doubt that very few of them ever sit down and leave a paragraph as it first comes into their head…. I have to find out where the idea wants to go.

As a young man, Burchfield thought he might become a nature writer and imagined adding his own illustrations as complements to his paragraphs. Realizing that his “outlook was visual rather than otherwise,” he pursued painting but kept writing close at hand, even, in early works, recording his feelings about a picture on its reverse side. The August North (1917) depicts a small peaked-roof house tucked back amid ominous woods and white petunias gaping like little mouths. On the back of the painting Burchfield described the gothic scene: “As the darkness settles down the pulsating chorus of night insects commences, swelling louder and louder until it resembles the heart-like beat of the interior of a black closet.”

Across the diaries, Burchfield attends to the smallest sights, sounds, and smells. The call of the veery, he writes in 1936, “will belong forever to rank green glades in June, hot garish sunlight, flowering Raspberry, and the smell of citronella.” Out on a drive near East Otto, New York, in 1965, he encounters a spectacular thunderstorm:

These were not the river-like bolts ordinarily seen in great masses of cloud, but complete wavy bars of blinding lightning, cold blue across a sky of hot saffron yellows, or yellow saturated dark clouds—unattached to the earth or the sky—existing free in space…

Like the otherworldly hues in his paintings, color in his written descriptions is feverish and wild: “A hot violet haze…combines with the hot green of the trees to reproduce shimmering blackish forms that quiver against the hot salmon-white and pale blue sky.”

At its best, writing about the visible world is itself a sensory endeavor—language that not only elicits a picture but that can itself be felt and seen. Burchfield admired the writing of contemporary naturalists such as Harold Borland and Edwin Way Teale, and Audubon’s Labrador journals were a revelation. He delighted in their record of “what I most want to know about the country—its weather, etc. as revealed in little things.” He read a host of nineteenth-century Scandinavian and Russian writers, as well as Willa Cather, Zona Gale, Emerson, Thoreau, and childhood favorites such as Kenneth Grahame’s paean to the natural world, The Wind in the Willows. In the 1959 interview, Burchfield recited a passage from his well-penciled copy of Sun and Storm, the 1939 novel by the Finnish writer Unto Seppänen:

Cuckoos were calling from everywhere as the sun sank to rest. All day long there had been a kind of yellow haze above the pine trees. The pollen from their blossoms even stained with saffron the surface of the lake. The swallows dipped so low in their flight that it seemed they were trying to nip the last of the evening wind from the tips of the grass blades.

Burchfield’s journals are filled with similar moments prolonged by pleasure:

Advertisement

But most delightful of all, it seemed, was to watch the sun-stars dancing on the tiny wavelets formed by an intermittent wind…. Far down the long pond we could see hundreds of glittering stars begin to dance, and then sweep up toward us in a bewildering wave on wave of glittering profusion, until the whole surface of the water in front of us was chopped by the brilliant tiny suns. Almost as if they could be heard.

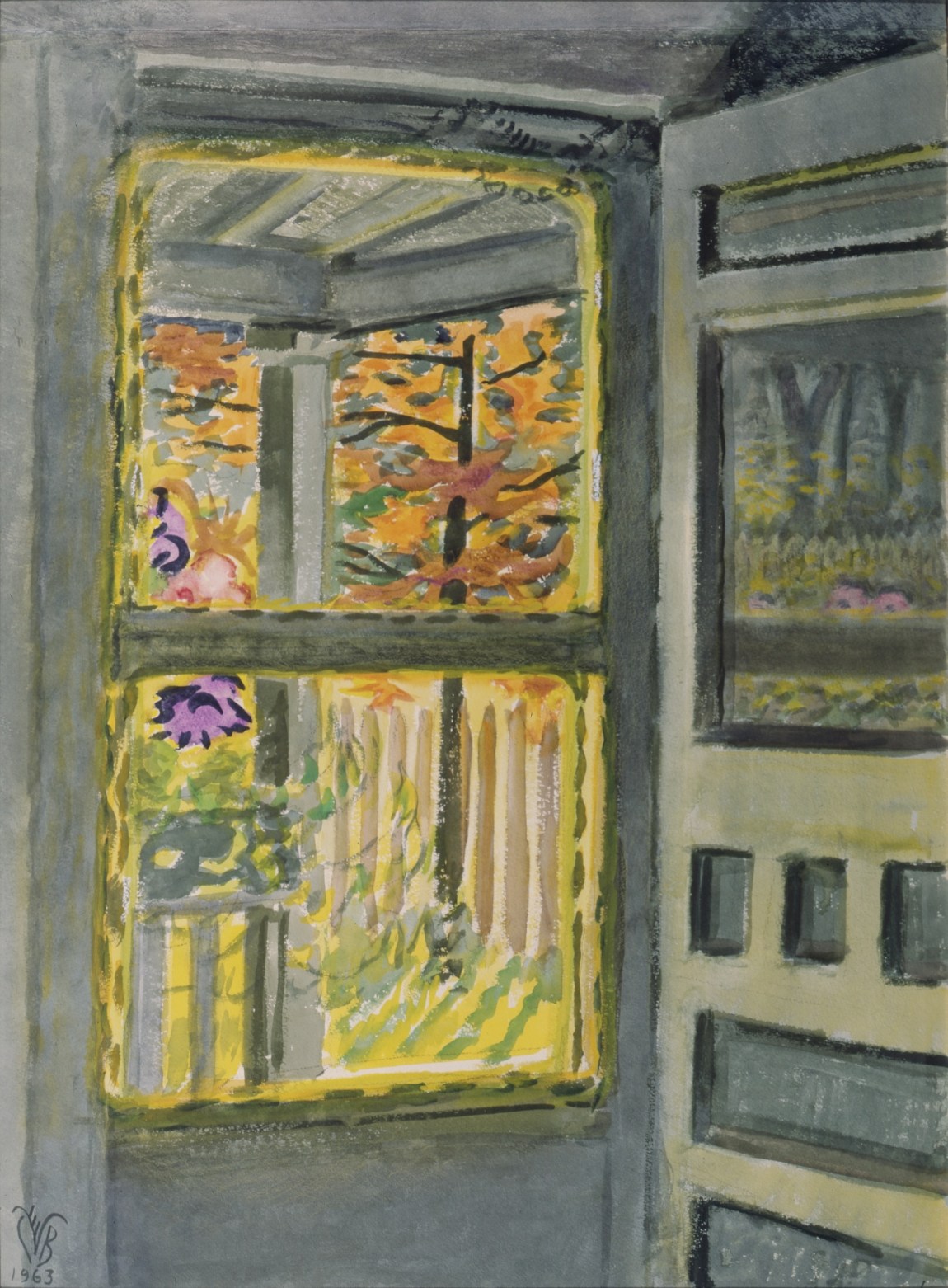

In his art he transforms these “little things” into cathedrals in the air. A late painting, October Outside (1963), offers a view of the yard just beyond the screen door of his studio. The gray-white interior comes alive with the reflected vibrance of the green grass, autumn foliage, and amethyst petunias framed by the door like a picture. The painting suggests both longing and gratitude—an Eden so close to hand. In his journal, when he spies a paperboy at work with a transistor radio slung around his neck, he is aggrieved on the boy’s behalf: “How can he hear the wind in the tree-tops? Or the song of a bird?”

*

Burchfield spent most of his life in rural areas or on the outskirts of cities. He was born in 1893 in Ashtabula Harbor, Ohio, about sixty miles from Cleveland. After his father’s death in 1898, the family moved south to Salem, near the border with Pennsylvania. Having graduated from the Cleveland School of Art in 1916, he won a scholarship to the National Academy of Design in New York but fled the “agony” of the city after just one day. Back in the countryside, his imagination took flight; his art was transformed. “Memories of my boyhood crowded in upon me to make that time also a dream world of the imagination,” he later wrote about 1917, which he called his “Golden Year.”

Throughout the 1920s, he worked as a wallpaper designer at M. H. Birge & Sons, living in Buffalo and then in Gardenville, New York, with his wife, Bertha, and five children. In 1929 he joined the Frank K. M. Rehn Galleries in New York (another client was Edward Hopper, whom Burchfield befriended around 1928, when Hopper wrote an admiring article about his work) and quit his job on the cusp of the Great Depression to paint full-time. The risk paid off. The Museum of Modern Art exhibited his early watercolors the next year—the museum’s first solo exhibition of an American artist—which helped launch Burchfield’s career. He showed his work regularly over the next three decades, mainly in the Northeast and Ohio, as well as in Paris and London, culminating, in his lifetime, in a six-venue survey that began at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1956. Burchfield was prolific even as his health began to fail. In 1966, a month before he died, he saw the inauguration of the Charles Burchfield Center, at the State University College at Buffalo.

In the 1930s, critics gathered Burchfield’s paintings under the umbrella of “American Scene painting” or “regionalism”—labels he detested, partly for their implied lack of sophistication. He preferred to be known as a “romantic-realist.” “It is the romantic side of the real world that I portray,” he wrote in a letter from 1940. “My things are poems—(I hope).” So, too, his writing: “What do trees feel like under this wind & storm & frost, sunlight, decay, leaf-falling and rain? Is that why they look so startled? Is that why houses are frightened?”

But nature offered Burchfield far more than painterly inspiration. It was the center of an informal belief system. As Weekly notes, he was a pantheist who, as he said, “worshipped nature with a capital letter.” His paternal grandfather had been an evangelical Methodist minister, but Burchfield was, through his atheist father, skeptical of organized religion. He reports in his journal that while on a walk with his then-fiancée, Alice, in 1915, “I asked her if any knew just what a prayer was, and declared that if I stopped to admire or sketch a tree, it was more of a prayer than meaningless phrases mumbled in a church.” His place of worship was amid the wind and sky and birds. Recalling his boyhood belief in goodness, he wrote in his journal that “then there was a sacredness to a sun-topped cloud seen in my June Saturday rambles; to the first soft downy hepaticas that pushed up thru the dry leaves; to the glint of cold light on the windblown hayfields of late June.”

He found a society in the natural world—the sustaining atmosphere that Whitman celebrated in Leaves of Grass—and frequently wrote about his own moods in relation to the outdoors. In 1915, while employed in the cost department of a metal manufacturer, he felt his intimacy with nature dissipating and testified in his journal about his reawakening: “I renewed my acquaintance with the beauty of an old-fashioned pink rose tonight.” He also describes his emotions through the metaphor of invented landscapes. At art school in Cleveland he complains of feeling depressed: “I have never longed for solitude as much as I do now. Strange phantom lands, in which I wander as a half-insane carefree being, loom up in my mind. I see enormous moonlit cliffs with water roaring at their bases.”

Advertisement

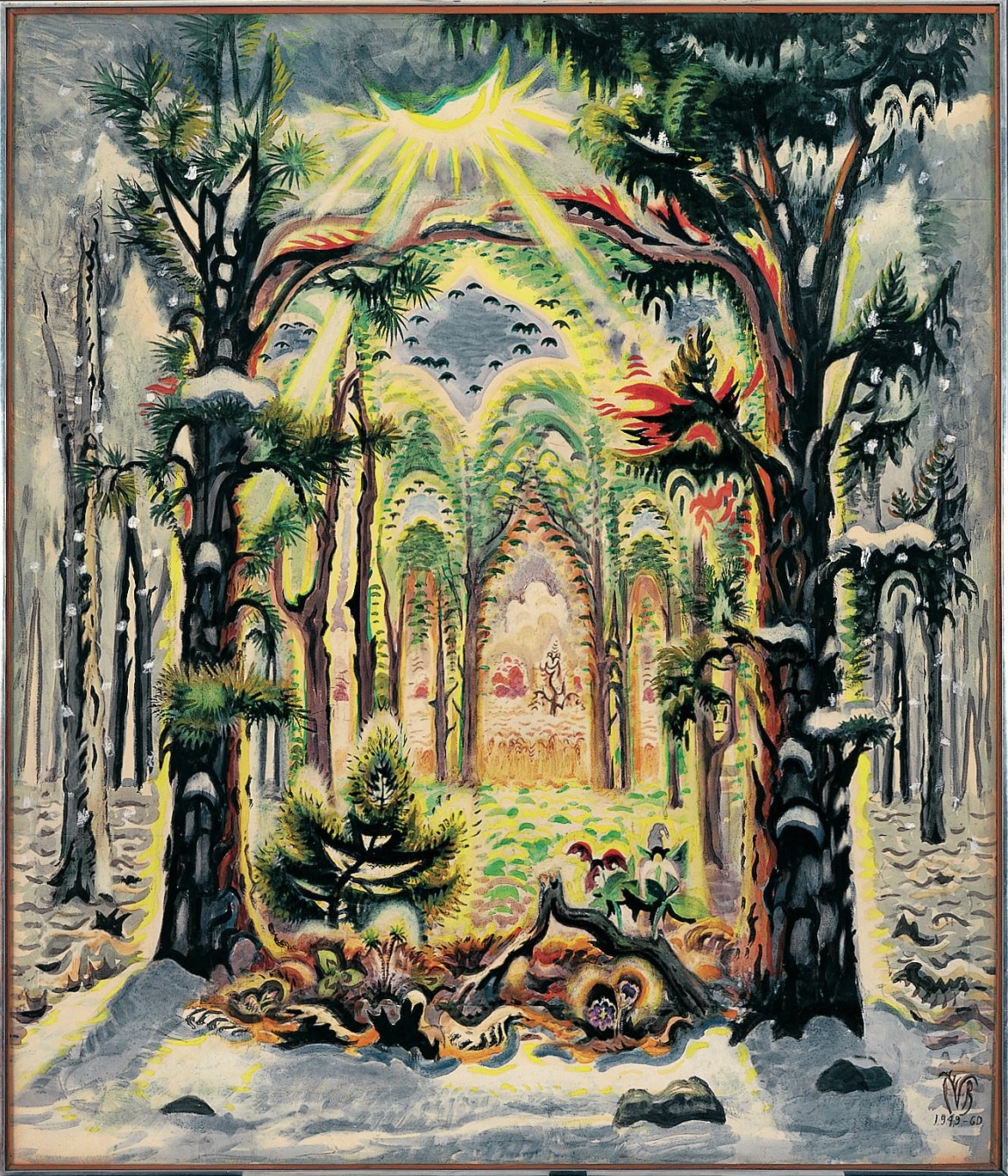

The Four Seasons (1949–60), one of a selection of works reproduced in The Sphinx and the Milky Way, echoes the architecture of a church. To look at the painting is to gaze down the nave of the forest—the wintry transepts demarcated by a pair of towering evergreens—leading to the distant apse, a modest dome shaped by the treetops. The scene is bathed in the sun’s golds and oranges as though refracted through a stained-glass window. Burchfield’s rendering here and in other paintings is attention taken to its highest degree; it is a particular kind of devotion that recalls Dickinson: “Some keep the Sabbath going to Church –/I keep it, staying at Home –/With a Bobolink for a Chorister –/And an Orchard, for a Dome –.”

In 1917, he began a painting that he would enlarge in 1952 called Song of the Telegraph, in which a row of quavering telegraph poles disappears into the distance beyond a stand of trees whose boughs join up in undulating peaks, like the steeple of a chapel. Crows drift by above, ghost riders in the sky. An entry from August 4, 1914, predicts the composition:

Listen long to the singing of the telephone poles. It sounds more weird & beautiful by moonlight. This is a solo played by the arch music master, the wind, as he draws his bow—a shaft of moonlight—across the wires.

Each pole has a distinct tone. A steady throbbing sound—the poles, once trees, still are full of life, which is expressed in this pulsating sound.Seems a voice from the centre of the earth.

Burchfield said that he was perhaps most influenced by music: Beethoven, Mozart, Hayden, and Vivaldi. (He also listened to Russian operas and Ukrainian folk music.) Sibelius ranked among his favorites. “All the torture of barrenness and indecision that this autumn assailed me are dissolved in this elemental music,” he writes in 1930 about Sibelius’s Symphony no. 2. “Pictures and ideas pour in upon me—my joy is almost too great to be borne.”

*

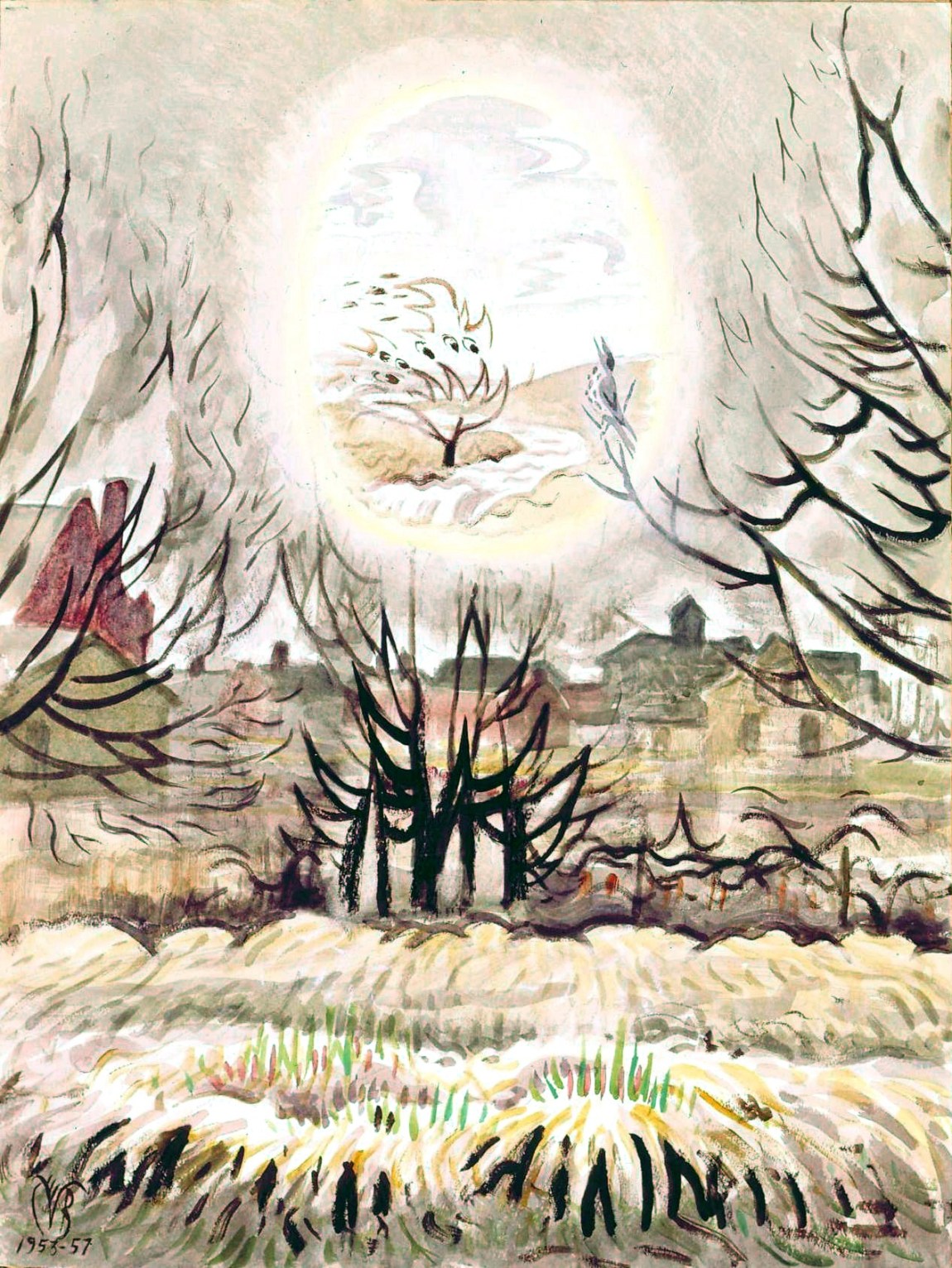

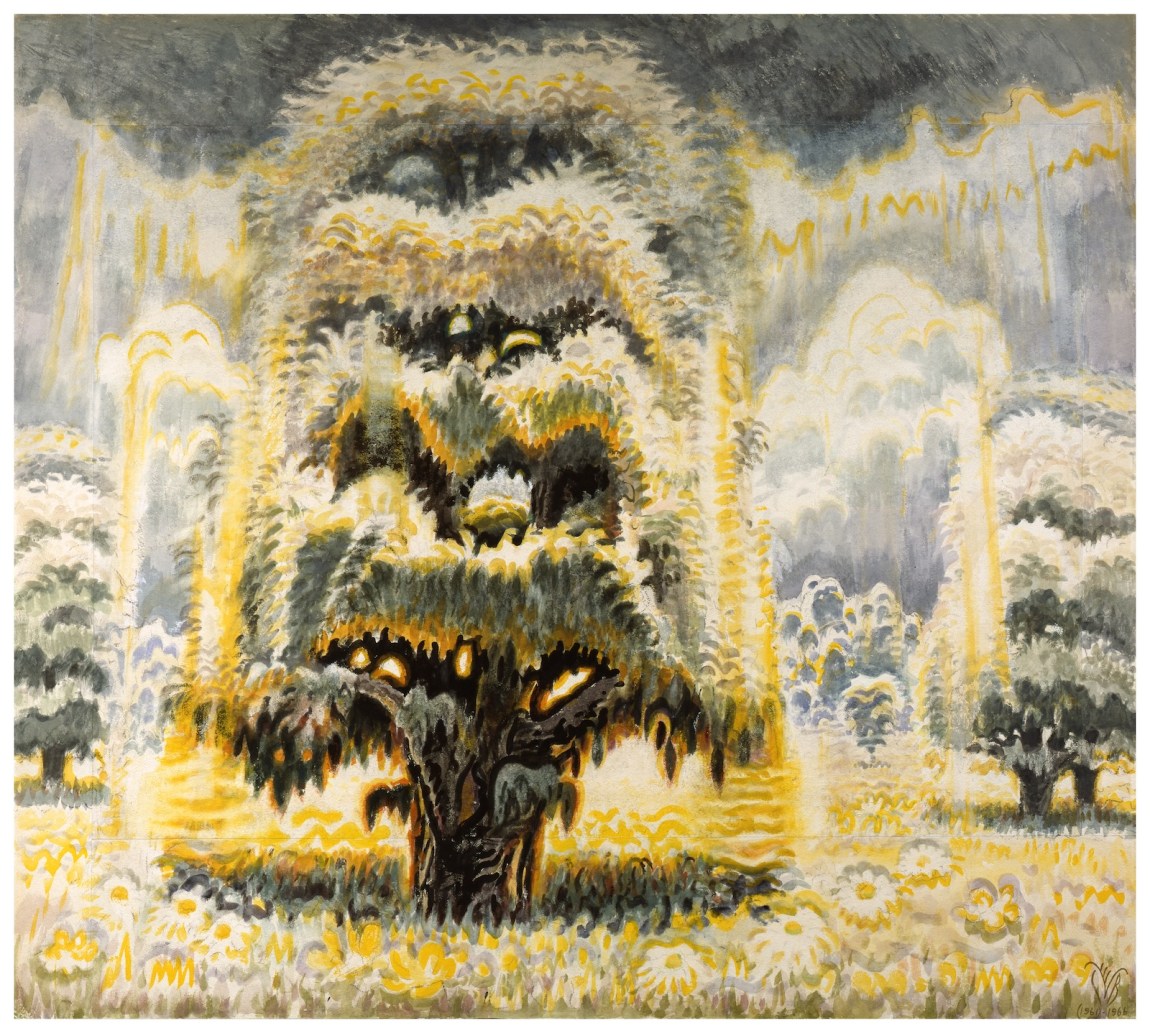

Particularly in the latter half of his career, Burchfield’s paintings seem to emerge from visions of some other place—infinity glimpsed in the strands of a spiderweb or in the eye of a sunflower. A giant, tiered chestnut dominates Summer Solstice (In Memory of the American Chestnut Tree) (1961–66), rising skyward from a meadow hazy with white and yellow flowers. Arrayed in an aura of golden light on the solstice, the tree is possessed of godhead. In the subdued gray-green Landscape with Vision (1953–57), the viewer faces a scrum of trees beyond which the roofs of a town are visible. An oval carves into the empty air above and admits a view onto a different scene, of windblown clouds in a pale blue sky and a tree and river amid rolling hills—a portal to a sunnier realm. These are visions born from the depth and quality of Burchfield’s looking. “It is as difficult to take in all the glory of the dandelion, as it is to take in a mountain, or a thunderstorm,” he writes in 1945. If the places in his paintings resemble views of another world—or as he once put it, “the eternal lands of the Spirit”—it is because he looked at his own with thoughtful intensity.

Burchfield’s interest lay more in nature than in human civilization, but he also painted the latter, primarily in the 1930s. End of the Day (1938) shows a handful of industrial workers trudging up an icy street from the factory to a row of ramshackle houses. Burchfield thought that though their situation might appear bleak, they are resolute, “and so they attain a rugged dignity that compels our admiration.” It’s no surprise that he defended Hopper’s depictions of small towns and cities against readings of them as irony or satire. Hopper wasn’t being sentimental either. Burchfield could recognize that he was painting the conflict between one’s inner life and the atomizing force of contemporary American society. Hopper saw a similar range in his friend’s paintings, writing in The Arts in 1928 that Burchfield’s work

is most decidedly founded, not on art, but on life, and the life that he knows and loves best. From what is to the mediocre artist and unseeing layman the boredom of everyday existence in a provincial community, he has extracted a quality that we may call poetic, romantic, lyric, or what you will. By sympathy with the particular he has made it epic and universal. No mood has been so mean as to seem unworthy of interpretation.

Burchfield’s paintings are empathetic whether he was picturing what he called the “humblest form” of buildings and workers or the uncanny respite of nature. “I hate the wallpaper factory,” he wrote of his job in 1923. “I long for more real human experiences—not personal, but belonging to all of humanity.” Nature, meanwhile, belonged to everyone and no one in particular.

Burchfield chastised writers who judged natural phenomena through the prism of their own feelings, reading their own melancholy into “otherwise joyful days” or projecting sadness onto “gray skies.” He thought that “an artist must paint, not what he sees in Nature, but what is there”—a distinction so fine that it may be impossible to detect; who we are always has an effect on how we see. Burchfield was no different. He wrote generously and tenderly of nature’s beauty in and for itself, but his paintings were, to him, more real than reality. He wrote in the foreword to a 1945 volume of his work that “when working directly from nature…not only am I trying to recapture the first vision or impression that attracted me (and which is all that is worth going after) but also the distillation of all previous similar experiences.” Derek Jarman, another acutely sensitive writer of nature, described this sort of untamed synthesis as “a landscape of past endeavors”—the new sitting right alongside the old.

In an entry from 1911, Burchfield ruminates on what he should record in his journals. At first he thinks only basic facts are fitting. Then he decides to fill out those bare bones with descriptions of his feelings about what he sees. Finally, he resolves to include his “imaginings, for they are a part of a person’s life.” This combination in writing supported his artmaking, which in turn nourished his sense of self. In 1938 he testified in his journal, “I like to think of myself—as an artist—as being in a nondescript swamp, alone, up to my knees in mire, painting that vital beauty I see there, in my own way, not caring a damn about tradition, or anyone’s opinion.”