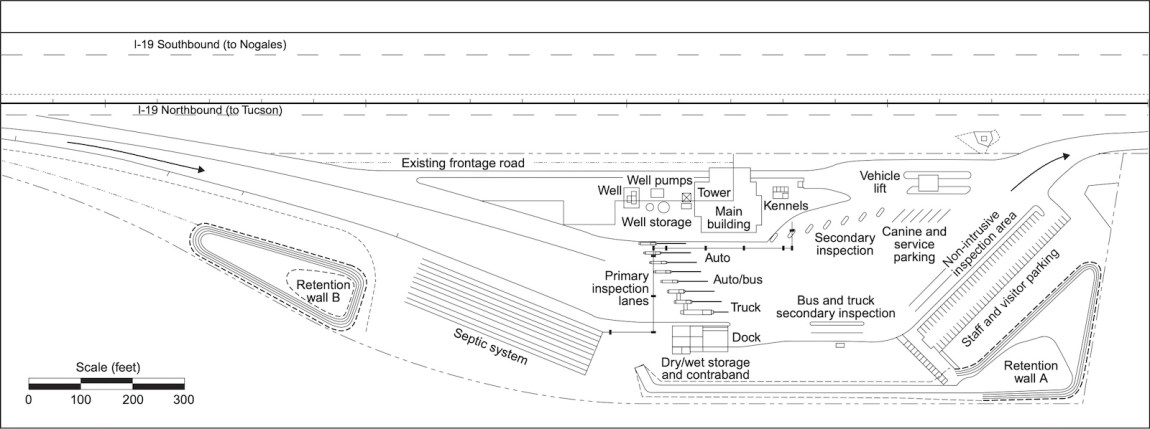

Judging from the architectural plans that the Border Patrol presented to Congress in 2009, the I-19 Border Patrol Checkpoint was supposed to be enormous. It was to be built in Tubac, Arizona, some twenty miles north of the conjoined border cities of so-called Ambos Nogales (“Both Nogales”). As freeway traffic approached, personal vehicles would be diverted into seven lanes with inspection booths. Later the engineers deemed the design insufficient: twenty-two lanes were needed. Passenger buses and commercial trucks would be directed to another inspection area, next to the parking lot built for the personal vehicles of the thirty-nine Border Patrol agents who would staff the checkpoint twenty-four hours a day. Elsewhere there would be kennels for drug-sniffing K-9s, a vehicle elevator for advanced searches, towers equipped with radar and other communication systems, a warehouse for seized contraband, a computer lab with access to databases of terrorists and organized crime organizations, and a detention center with space to house up to three hundred “illegal aliens.”

All of this was necessary, the Border Patrol claimed, because most undocumented migrants entered the country through southern Arizona. The Border Patrol has nine sectors spanning the US–Mexico border, but at the time that the plans were presented nearly half of borderland apprehensions took place in the Tucson Sector alone—241,673 of 540,865 in Fiscal Year 2009.

Today, however, the I-19 checkpoint is little more than a metal tent in the middle of the desert. The complex the engineers dreamed of was never built. In the mile leading up to the checkpoint, signs warn drivers to slow down. Then traffic cones appear, dividing the lanes of waiting cars. At the permanent checkpoints of Texas, no one passes without verbally affirming their citizenship or presenting documents to substantiate another form of legal presence. That obligatory question is often followed by additional inquiries into one’s activities. But in Arizona the agents often don’t even stop the cars. They just wave and keep the traffic flowing.

After fourteen years in the same location, the I-19 traffic stop is still legally considered temporary, making the Tucson sector—the one the authorities treated with such priority—the only sector along the US–Mexico border with no permanent checkpoint. (Across the other eight sectors, there are thirty-two.) This state of limbo has little to do with concern for the human right to free movement. The argument that managed to stop the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) came from one of the US’s most storied traditions: the defense of the value of one’s private property at all costs.

*

An interior border checkpoint is an oxymoron. How can you conduct a border check in the country’s interior? The answer, according to Customs and Border Protection (CBP), is simple. The border is not a line but a wide zone of enforcement that extends a hundred miles from the perimeter of the country inland. Inside that zone of exception—which includes two-thirds of the US’s population, since the country’s perimeter includes the coasts—the government grants CBP officers the unique right to detain, interrogate, and arrest individuals without a warrant.

From another point of view, however, the US–Mexico border needs to be as thin as possible. Thirty years ago the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect, enabling US companies to move their manufacturing to Mexico without protectionist tariffs, and offering large new consumer markets to producers of commodities like corn and pork. Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton promised that the deal would benefit both US businesses and workers. Mexican presidents Miguel de la Madrid and Carlos Salinas de Gortari saw loosening protectionist measures as a way to achieve economic parity with the rest of North America. Under the new regime, goods were to move back and forth across the international boundary without friction.

How do you reconcile the “control” of border control with the “free” of North American Free Trade? The answer, according to the Border Patrol, is again simple: you build larger and larger checkpoints. Interior checkpoints are one part of a surveillance strategy that the Border Patrol calls “defense in depth.” That strategy consists of three geographically distinct layers, each one further from the border. The first is “line watching,” or observing the border line itself. The second are roving patrols—small groups of agents that move throughout the areas where they believe migrants are likely to be traveling. The third are interior checkpoints. “You can’t stop everything at the border, so what you do is close the exit routes,” an agency spokesperson told me.

The history of interior checkpoints predates the 1924 creation of the Border Patrol. During the 1930s, they were used as tools in Great Depression–era deportation drives. After the Bracero Program, which brought Mexican workers to the United States during World War II, ended in 1965, their use started increasing again, as many people crossed the border undocumented to return to the jobs they had previously held with authorization.

Advertisement

The legal basis for the checkpoints was codified in a 1976 Supreme Court case called United States v. Martinez-Fuerte. Amado Martinez-Fuerte, a legal resident of the US, was stopped at a checkpoint in San Clemente, California, with two passengers who had crossed the San Ysidro port of entry using false papers. He was charged with two counts of violating the US’s law against “bringing in and harboring certain aliens.” When he contested the charges on the grounds that they violated the fourth amendment’s protection against unreasonable search and seizure, the Supreme Court determined that the Border Patrol’s checkpoints were permissible under the amendment and that agents could refer individuals to secondary inspection on grounds that would not justify other types of police searches—including suspicion based on racial profiling.

*

In principle, inland checkpoints were meant to take advantage of the element of surprise. So-called “tactical” checkpoints changed their location each week, which meant that migrants and their guides wouldn’t know where to expect them. The problem was that the Border Patrol had to obtain new permits from the state highway department with each change. Since this was an onerous bureaucratic process, the agency decided to make their checkpoints permanent.

The exception was Tucson. In 1999, with the support of Representative Jim Kolbe, then a Republican, a clause was introduced into the year’s Omnibus Consolidated and Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act: “No funds shall be available for the site acquisition, design, or construction of any Border Patrol checkpoint in the Tucson sector.” He considered the permanent checkpoints to be bad strategy: guides and smugglers could simply learn to avoid them.1 “We already have a permanent checkpoint—it’s our border,” he told the conservative Washington Times in 2003. Congress renewed Kolbe’s stipulation every year until 2006. An additional clause approved in 2003, after other sectors’ checkpoints had been constructed, required the Border Patrol to move the Tucson checkpoint every two weeks.

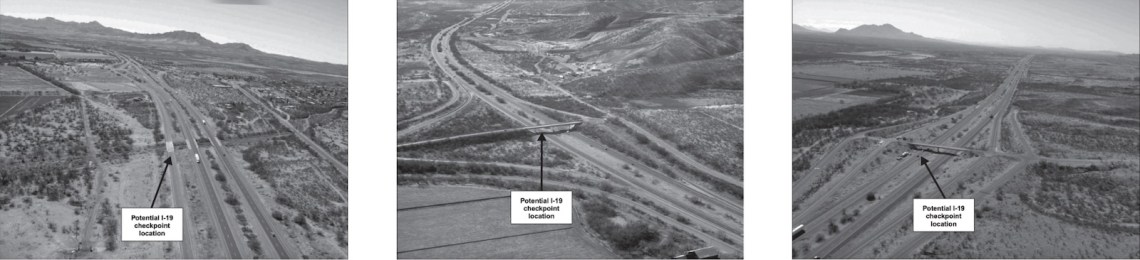

By 2007 Kolbe had retired. The Border Patrol seized their opportunity to fix the location of I-19’s nomadic checkpoint and started making plans to transform it into a permanent facility. The agency’s facility design guide directed them to place checkpoints at sites with good visibility and few escape routes. They selected such a location north of the town of Tubac and, as though really sticking it to Kolbe, designed the most ambitious checkpoint in history.

Checkpoints were not new, but the idea of making them massive, permanent installations was the result of two crucial events: NAFTA and September 11. In the aftermath of NAFTA’s January 1, 1994 inauguration, both truck traffic and migration increased. By 2000 imports from Mexico had risen 170 percent. At the same time, millions of so-called “NAFTA refugees” migrated north, leaving areas of rural Mexico that had seen their local economies eviscerated by the import of US commodities. The physical footprint and symbolic weight of the interior checkpoints ballooned because of a tension central to the agreement: NAFTA promoted the free movement of capital and goods, two of the three components of the classic neoliberal conception of free trade, but didn’t extend the same liberty to the third, the workforce. In the free-trade era, checkpoints had to facilitate the movement of semi-trailers full of merchandise and stop people whose lives had been upended by economic destabilization.

In 2003, in response to the attack on the Twin Towers, President George W. Bush created Customs and Border Protection as an agency of the newly formed DHS, providing the border agency with funds and a directive to fight terrorism. (The Border Patrol’s annual budget has increased tenfold since 1994, and CBP’s threefold since 2003.) With this change, the checkpoints took on another symbolic meaning: they contributed to the obsession with security that dominated US policy during the War on Terror. That’s when they really started to look like fortresses.

For the I-19 plans, the engineers based their design on a recently constructed checkpoint on I-35 north of Laredo, Texas: a slab of asphalt chiseled out of thick green forest that on its completion in 2006 was the largest checkpoint in the country. But Tucson sector officials at the time determined that even the Laredo checkpoint’s fifteen acres weren’t sufficient for operating the X-ray scanner they planned to install, or for “safe truck maneuvering.” The I-19 checkpoint would need eighteen acres.

Before construction could start, the law required the Border Patrol to publish an announcement in local newspapers soliciting public comment for a thirty-day period. In Laredo they didn’t receive a single public comment, so the response in Tubac took them by surprise. The town’s one thousand inhabitants worried that the checkpoint would have negative consequences for the boutique hotels, art galleries, and golf resorts that made up the local economy. It could, they feared, damage the real estate market of Tubac and of the nearby communities of Green Valley and Sahuarita, both growing suburbs of Tucson. The owner of one local business printed posters that read “SECURE THE BORDER AT THE BORDER,” along with an outline of the United States filled in with stars and stripes. Local residents took the posters to protests. On one occasion, a dozen demonstrators taped them to the back windows of their cars and drove through the checkpoint en masse, over and over again, for hours.

Advertisement

The group that led opposition to the checkpoint was called the Santa Cruz Valley Citizens’ Council. It had been founded in the 1980s with the intention of bringing together the interests of the area’s homeowners’ associations. The director of sales of the real estate agency Brasher Realty—one of the founding members of the citizens’ council—told a local paper that many buyers had rescinded their offers when they learned that they would have to pass through the checkpoint every day. The plans, he said, had already caused more than five million dollars in losses.

In response to the protests, Representative Gabrielle Giffords introduced a clause in the 2009 appropriations bill that prohibited DHS from finalizing its plans to build a permanent checkpoint in the Tucson sector until the Government Accountability Office (GAO) had completed a review of all the permanent checkpoints in the Southwest. The checkpoint’s opponents calculated that this would delay construction two or three years. Instead, fourteen years later, the planned facilities have never been constructed.

The GAO published its review in August 2009. The researchers admitted that the checkpoints seemed to contribute to the Border Patrol’s mission but ultimately concluded that the agency had been so negligent in tracking legally required data that evaluating the checkpoints was practically impossible. At one checkpoint, agents had counted all apprehensions within a 2.5-mile radius as apprehensions at the checkpoint. At another, instead of submitting the number of apprehended people who were referred to federal law enforcement—an estimate of the checkpoints’ efficacy for combating terrorism—they had counted the number referred to any type of law enforcement, including local police. Meanwhile the Tucson sector officials refused to share their statistics regarding apprehensions and seizures of contraband, on the grounds that doing so could benefit the migrants and guides seeking to evade the checkpoint.

In 2012, a study by the Udall Institute of Public Policy at the University of Arizona concluded that the tubaqueños were right: the checkpoint had indeed negatively affected the local real estate market. “There’s no way it cannot have affected our business since they made it permanent,” Garry Hembree, former president of the Tubac Chamber of Commerce, told the Associated Press. “I don’t know how they put that up without considering that.” The report was, it seems, the nail in the coffin for the Border Patrol’s plans.

*

Today the largest interior checkpoint in the United States sits on Highway 281 near Falfurrias, Texas, sixty miles north of the border town of McAllen. Falfurrias became infamous in 2012 as an epicenter of migrant death in the borderlands precisely because of the checkpoint, which people died trying to circumvent. Despite news coverage of the crisis and activism against it, DHS decided to continue with its plans to expand the checkpoint, arguing that it had to grow to accommodate the increasing number of trucks ferrying cargo north from the maquiladoras (foreign-owned factories operating under free trade policies) in Mexico’s border zone.

The Falfurrias checkpoint, which cost thirty million dollars, was inaugurated in May 2019. It has eight inspection lanes, K-9 kennels, and a technology called “Z portals” that can take an X-ray of a car from six simultaneous perspectives, which had previously only been used at ports of entry on the border itself. Its shifts are the bane of local agents. One former Falfurrias agent wrote on a Border Patrol forum that those assigned to the town call it “Falcatrazz”: “Nearly every Agent i have met there hates their life there…What sucks the life out of Agents is the mega huge multilane highway checkpoint that they are sent to nearly every day they work.”

Susan Kibbe, president of the South Texas Private Property Rights Association, told me that local landowners didn’t protest the construction of the Falfurrias checkpoint. They would prefer if the Border Patrol stuck to patrolling the border, she explained, but by now they are used to the structure. They weren’t concerned about real estate prices because most of the properties surrounding the checkpoint “are large ranches that aren’t going to be sold; they’re passed down within families over multiple generations.” Still, Kibbe added, it bothers her and others that only two or three of the eight lanes are staffed, even though DHS spent millions of dollars to build the checkpoint. The rest remain closed.

In the past thirty years, the border between the US and Mexico has become louder, more violent, and more paved-over. The construction of roads and warehouses has caused the widespread loss of wildlife habitat; the increased truck traffic has contributed to high rates of asthma among children in the Rio Grande Valley. The specter of undocumented migration has provoked the continual expansion of surveillance and police facilities, which multiply even as their efficacy remains unclear. The metallic shell that spans I-19 near Tubac could be just as effective, or ineffective, as the gigantic checkpoint of Falfurrias. We’ll never know: there’s no way to ascertain how many people pass through the borderlands undetected, or what quantity of drugs are smuggled in the holds of trucks. We do know that checkpoints account for just 2 percent of Border Patrol apprehensions, and that 40 percent of these are seizures of small amounts of marijuana from US citizens.

Then again, American border policy, at least in recent years, has been determined not based on evidence but to stoke fear and paranoia. The US–Mexico border is no exception. Walls—and the infrastructure that supports them, like checkpoints—offer a sense of security even as they “fail,” in the words of the political theorist Wendy Brown, “to block or repel the transnational and clandestine flows of people, goods, and terror.” No matter the size of a country’s wall or its checkpoints, human migration and the trafficking of goods continue. The spectacle of the restriction of movement is less impressive from up close.