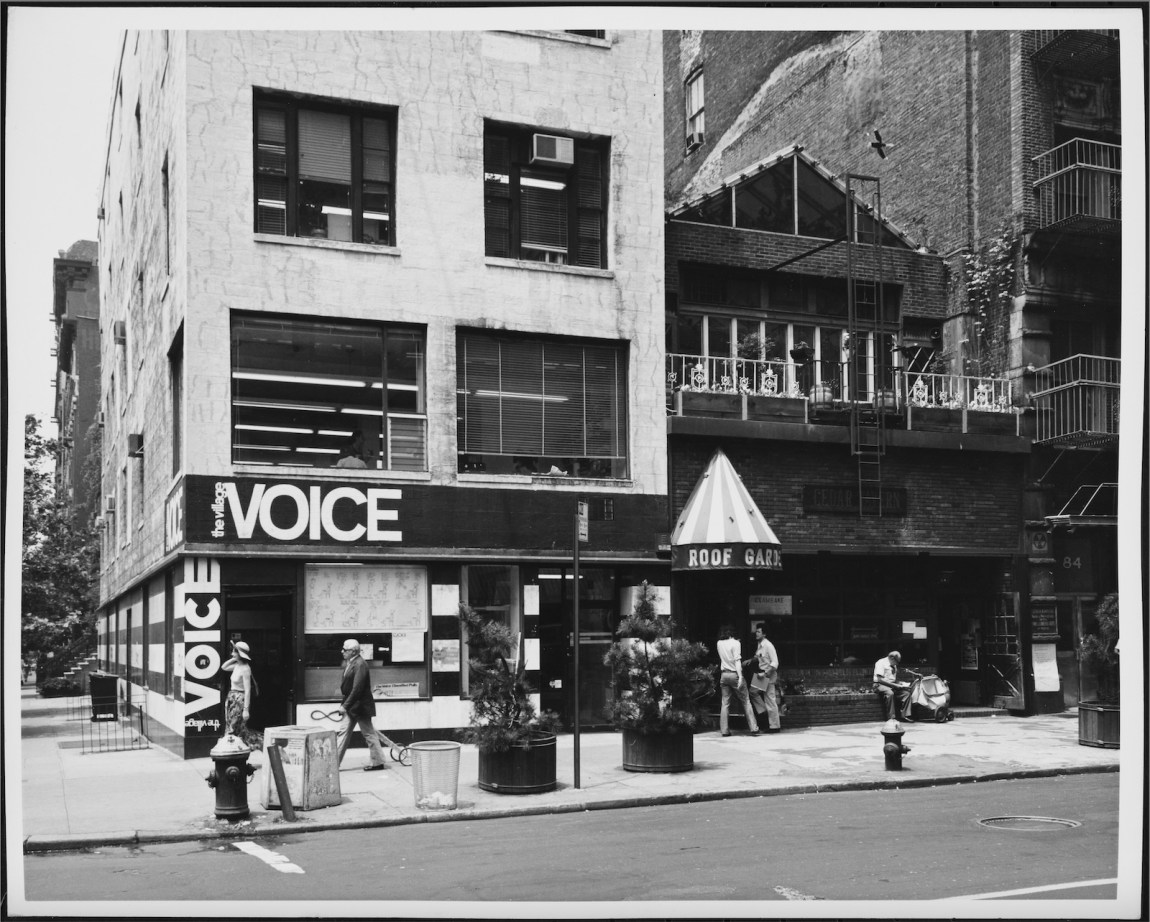

In December 2016 I was sitting in The Village Voice’s fluorescently lit office in New York City’s Financial District, waiting to interview for a job. There was a strange flutter in the air; big news had just arrived. My phone had buzzed on the elevator ride up with a push alert bearing a New York Times article: “The Village Voice Names a New Top Editor, Again.”

The last decade had not been kind to the Voice. The paper had been hollowed out by its previous owner, the New Times newspaper chain. As the journalist Tricia Romano remembered, during the “years that New Times ran the paper, it was death by a thousand cuts, as they slowly fired everyone.” Among those forced out were staffers who had worked there for decades, including Robert Christgau, J. Hoberman, Nat Hentoff, and Lynn Yaeger. In 2015 the paper’s ownership changed hands again, this time to a billionaire named Peter Barbey. Observers treated the acquisition with cautious optimism. “It is one of America’s great newspaper brands in terms of potential by the pound,” Barbey said. In the year that followed, he replaced the Voice’s editor three times.

That day in December I was shuttled from the waiting room into a windowless back office. I remember the whispers and the tense atmosphere: the journalists here were used to upheaval. After this latest announcement, they were clearly imagining more bad headlines to come.

I had begun my career in the media a year earlier, at the music website Pitchfork. I thought I’d be in graduate school by then, but meeting deadlines and getting free tickets to concerts was more exciting; the idea of writing for the public was a happy accident. It would have been gratifying to work at the local paper I had read growing up: free copies of the Voice, piled up in those red boxes, kept me company as a teen in the far reaches of Queens. My interview did not go well: everyone (me, the editors I talked to, all the people nervously shuffling around the office) seemed worried about the institution’s health. When I left the office, I didn’t expect to hear from them; I went back to my desk at Pitchfork later that afternoon and wondered if I had dodged a bullet. Maybe things would be safer at Condé Nast.

*

Eight months later, in the summer of 2017, another bad headline did follow. “After 62 Years and Many Battles, Village Voice Will End Print Publication,” the Times announced. Barbey hadn’t just run the paper into the ground; he had killed it.

It was a year filled with similar news. In digital media, the “pivot to video,” a social media–fueled shift in strategy from written content to short videos made on the cheap, had wiped out dozens of jobs from Vice to MTV News. The previous year Dan Fierman, of ESPN’s Grantland, having been hired as publisher to revamp MTV’s editorial arm, had gone on a hiring spree of name-brand writers. When layoffs were announced, the company explained that it was “shifting resources into short-form video content more in line with young people’s media consumption habits.”

As for print media, this latest blow to The Village Voice seemed sadly inevitable. Years of declining ad revenue—funneled, now, into Craigslist and Google and Facebook—had shuttered or diminished many papers around the country, especially local alt-weeklies, the format the Voice helped invent. Fewer than two years after I interviewed at the Voice, its editorial operations were shut down and most of its staff was laid off.

At the end of 2020 Brian Calle, a media executive from Los Angeles, bought the paper and announced plans to revive its website and restart its print edition as a quarterly. The news was met with alarm. In 2017, after Calle acquired LA Weekly, a sister publication of the Voice, he proceeded to ruthlessly gut it, showing most of the newsroom the door. There was no staff left for him to fire at the Voice (in fact he hired a former editor at the paper named Bob Baker), but its ramshackle website and hard-to-find print edition give the impression of a ghost ship. Pitchfork, too, has become a husk of what it was: earlier this year, Condé Nast executives decided to merge the site into GQ, firing more than half of the full-time editorial staff in the process.

To work in American media in the twenty-first century is to live as if the end is near. Your job, your publication, and your lifestyle are always on the verge of crumbling. It’s easy to wax nostalgic about a time when journalism was a more esteemed profession, or at least a more stable and better compensated one. But dread was the prevailing mood even when publications were thicker with ads and paid classifieds. In 1978 Kevin Michael McAuliffe wrote a history of The Village Voice called The Great American Newspaper. By then, he declared, the publication was already in decline: the paper’s pluck and lively spirit were destined to wither away as it faced its first crisis of succession, brought on by a series of new owners—first the patrician society man Carter Burden, then Clay Felker, editor of crosstown rival New York, and finally, worst of all, Rupert Murdoch.

Advertisement

“It would survive somehow,” McAuliffe wrote. “But the magic and the glory that had been there would never return.” The Voice, from this point of view, might be seen as the canary in the coal mine, a preview of what was to come for the industry: bitter divides between management and labor that necessitated the creation of a union; the inability to overcome the economic headwinds brought on by the ruthless logic of the Internet; the mad, misbegotten hope that some new, more benevolent owner might save the place. But the paper’s story can’t be reduced to a death foretold. There’s much to learn from the life of the Voice.

*

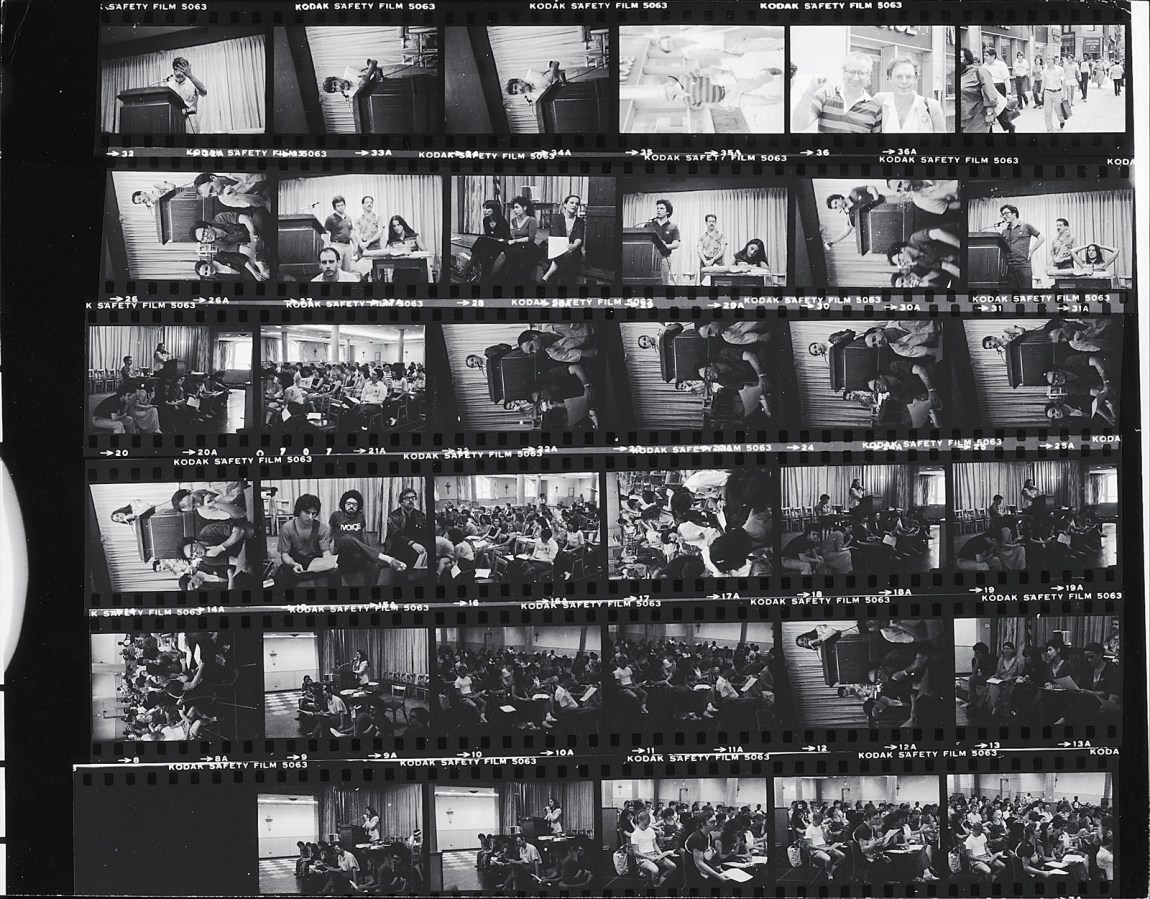

Romano is the author of a new book about the paper, The Freaks Came Out to Write. It’s a door-stopping, decades-spanning oral history stitched together from more than two hundred interviews she conducted as well as materials drawn from the oral history archive at Columbia University and other secondary sources: podcasts, books written by staffers, the like. Romano is well suited to chronicle the paper’s rise and fall. A former nightlife columnist and reporter at the Voice in the 2000s, she was also a witness to its twenty-first-century decline.

The book’s short, episodic chapters detail important events in the paper’s history—from its founding in 1955, with the help of Norman Mailer, to its reporting on Stonewall and the AIDS crisis—and survey the forms of writing it pioneered, including personal essays and cultural criticism about emerging genres like graffiti and rap. The Freaks Came Out to Write presents the Voice as a colorful and often fractious institution, with much screaming, performing, and brawling, both in its pages and in the hallways of its office. More than once the jazz critic Stanley Crouch came close to physical altercations with coworkers over disagreements both editorial and musical.

In 1962 Dan Wolf, who cofounded the paper and served as its first editor, described the Voice’s mission as an attempt to open a newspaper’s pages not only to trained journalists but also to people who had something to say:

The Village Voice was originally conceived as a living, breathing attempt to demolish the notion that one needs to be a professional to accomplish something in a field as purportedly technical as journalism. It was a philosophical position. We wanted to jam the gears of creeping automatism.

Staffers told McAuliffe that as an editor Wolf did not handle “copy” so much as “people.” What this meant, Louis Menand wrote in a 2008 essay on the Voice for the New Yorker, is that the paper “had to be prepared to publish what writers wanted to write. So, on the one hand, the Voice was under-edited; but, on the other hand, it got material that no other publication did, because no other publication would have attracted it or known what to do with it.” Among the writers whom Wolfe and his coeditors—notably Jerry Talmer, who went on to found the Obies—recruited in the paper’s first decade and a half were Vivian Gornick, who was hired to cover culture and second-wave feminism; Jonas Mekas, avant-garde film’s great evangelist; and Mary Perot Nichols, a Village housewife-turned-muckraker who showed up at the Voice’s offices complaining that they had overlooked Robert Moses’s proposal to ram an expressway through the middle of their neighborhood.

“A lot of the people [we] hired,” the longtime Voice editor Richard Goldstein told Romano, “were effectively amateurs as writers but had amazingly interesting sensibilities and were totally attuned to the subjects they wrote about.” The staff writer Lucian K. Truscott IV underscores the point:

You could read a Village Voice story, and not only were you learning what was going on in the world, whatever the person was writing about; you were also reading about the person that wrote it, so you were getting a sense of who this person is, and where he or she is coming from. When Susan Brownmiller, Claudia Dreifus, and Vivian Gornick and those women were writing about their lives as women in the early days of feminism, that was what feminism was. It was who they were, and why they were like that, and they were willing to tell you, out loud, in print, who they were, and why they felt the way they felt.

The result, he concludes, was a sense of intimacy “between Village Voice writers and Village Voice readers.” By the end of the 1960s, McAuliffe discovered, those readers were on average not denizens of New York’s underground but rather affluent thirtysomething professionals. Menand summarized his findings:

Advertisement

Almost ninety per cent of Voice readers had gone to college; forty per cent had done postgraduate work. Most had charge accounts at major department stores, such as Bloomingdale’s. Most owned stock. Twenty per cent were New Yorker readers. The Voice was the medium through which a mainstream middle-class readership stayed in touch with its inner bohemian.

One wonders why this demographic remained committed to the paper. Perhaps they valued the its variegated and idiosyncratic contents: Jill Johnston’s all-lowercase lesbian separatist personal essays, Jules Feiffer’s dyspeptic cartoons of modern life’s indignities (dating, crumbling infrastructure, the problem of Dick Nixon). Or it could be that they were drawn to the back of the book—the cultural reporting and criticism that, for many readers in New York and elsewhere, defined what was tasteful and cool.

*

The Voice was designed to evolve with the city it called home. It began as an idealistic, almost anti-ideological beatnik paper focused on the Village and its coffeehouse-frequenting inhabitants. By the end of the 1950s it had developed a reputation for picking fights with local power brokers. “Its first crusade,” Richard Goldstein told Romano, “was overthrowing the boss of Greenwich Village, Carmine DeSapio, and replacing him with a young Reform upstart named Ed Koch.” In the paper’s early years Nichols was “pounding away at Moses,” as Fancher puts it, “week after week.” The Voice receptionist Diane Fisher recalled that “Mary may be the only layman in the whole world who read the capital budget from the first item to the last.” Later, when Robert Caro was struggling to write The Power Broker, Nichols helped him secure carbon copies of Moses’s papers hidden in a Parks Department garage.

In the following decades the paper became a hub for exposés on the city’s most corrupt and powerful. It ran dogged early reports on Donald Trump’s real estate grifts, the symbiotic relationship between New York City’s cops and criminals, and backroom deals and gladhanding at city hall. The standard-bearers for this reporting were Jack Newfield—inventor of the Voice’s famous annual front-of-the-book “10 Worst Landlords” list—and Wayne Barrett, who tussled with Koch and Trump. In other respects the Voice could be nakedly partisan. Its relationship with Koch was at first particularly cozy. The paper was integral to his rise: it threw its weight behind him and his group, the Village Independent Democrats; tipped him off to the excesses of his rivals; and even hired him briefly as its lawyer. Then, when he became mayor in the late 1970s and cultivated a robust patronage system, the Voice turned on him: “Newfield decided he was like the Antichrist,” as someone put it to Romano.

Meanwhile, by the end of the 1960s the paper had also evolved into an important organ for the city’s social movements. One of Gornick’s first reports on women’s liberation arrived in November 1969. “The fact is that women have no special capacities for love,” she wrote,

and when a culture reaches a level where its women have nothing to do but “love” (as occurred in the Victorian upper classes and as is occurring now in the American middle classes), they prove to be very bad at it.… The woman who must love for a living, the woman who has no self, no objective external reality to take her own measure by, no work to discipline her, no goal to provide the illusion of progress, no internal resources, no separate mental existence, is constitutionally incapable of the emotional distance that is one of the real requirements of love. She cannot separate herself from her husband and children because all the passionate and multiple needs of her being are centered on them. That’s why women “Take everything personally.” It’s all they’ve got to take.

A decade later, Ellen Willis was reflecting on motherhood and its place in the left: “The institution of the family, and the people who enforce its rules and uphold its values, define the lives of both married and single people, just as capitalism defines the lives of workers and dropouts alike.” Abortion was among the paper’s concerns from early on. Throughout the 1960s, writers like Susan Brownmiller and Marlene Nadle offered sympathetic portraits of abortion providers and defended a woman’s right to determine her own reproductive health. But the paper’s desire to remain somewhat neutral—its refusal to, as one contributor put it to Romano, “become ‘the voice’ of any faction”—also allowed an anti-feminist, anti-abortion stance to develop in its pages. Nat Hentoff, originally a jazz critic, became one of the leading liberal voices for the pro-life movement.

The paper’s coverage of LGBTQ affairs got off to a bad start, too: one of its first stories on the riot at Stonewall called the protesters “the forces of faggotry.” But the editors were open to criticism and agreed when protestors from the Gay Liberation Front demanded they no longer use the slur. By the start of the 1980s the paper’s coverage of gay life in New York stood out, from its annual queer issue—edited by Goldstein—to its dedicated coverage of the AIDS crisis.

McAuliffe implied that the Voice might become more mainstream and conventional as it entered the 1980s. Instead its staff came to include writers and editors who could cover race, class, and popular culture with authority: Greg Tate, Thulani Davis, Nelson George, Hilton Als, Joe Wood. Tate’s 1989 essay “Jean-Michel Basquiat, Flyboy in the Buttermilk” remains among the most influential pieces of criticism the Voice ever published: not just an assessment of the painter a year after his death but a broader consideration of the price Black artists paid to be included in the avant-garde and the need for critics and artists of color to sketch out an aesthetic space outside what their white peers could imagine. About his own newspaper’s art coverage, he implied that much work remained to be done: “It is easier for a rich white man to enter the kingdom of heaven than for a Black abstract and/or Conceptual artist to get a one-woman show in lower Manhattan, or a feature in the pages of Artforum, Art in America, or The Village Voice.”

Throughout his history of the Voice, McAuliffe argues that it was uniquely a writer’s paper as opposed to an editor’s paper, a place where talent could be nurtured and cultivated. He was wrong about what would eventually kill it—going mainstream was a small problem compared to the ones the paper had to confront when the industry’s economic model changed. But he was right about the writing. Each generation that passed through the Voice created its own idiom, its own way of seeing the city.

*

The Voice owed its financial success to good timing, canny marketing, and sheer luck. The luck came in the form of two newspaper strikes, in 1962 and 1965, which allowed the paper to expand in the brief absence of competition: Menand reports that, after the 1962 strike, “circulation jumped from seventeen thousand to forty thousand.” (Another byproduct of the 1962 strike was the creation of The New York Review.) After 1965, he continues, they “consolidated that gain, and the Voice became a Manhattan weekly,” swelling with apartment listings, classifieds, and ads.

Those profits weren’t exactly shared with the staff. As the paper’s profile grew and its business stabilized, Wolf and Fancher became wealthy men, but they still relied on freelancers who were either poorly paid or worked for free. They published stuff other papers wouldn’t, but they didn’t pay the same rates as other papers, either. Only when Rupert Murdoch bought the Voice in 1977, three years after Fancher and Wolf were pushed out amid the paper’s brief merger with New York, did freelancers and staffers unionize, finally securing living wages. (A pioneering aspect of the Voice contract was that it gave even freelance contributors vacation days and other benefits.)

What killed the Voice, according to Romano and all the paper’s other eulogists, was the Internet. It is relatively easy to draw a straight line from the invention of Craigslist to the beginning of the Voice’s decline. Leonard Stern, the paper’s owner from the 1980s until the early 2000s, told Romano that he heard about the listings site from his son, who used it to hire an au pair. In that moment, he said, he knew the Voice was never going to be profitable again.

In the mid-1990s Stern made the paper free, abandoning the subscription business for a model that relied on sheer scale. (In part, the paper’s management worried about the growth of rival publications, like the free alt-weekly New York Press.) Many writers at the time bemoaned the move. Laurie Stone, a critic and columnist, told Romano it “undermined the idea that this was something of value to pay for.” Not charging a dime for the paper, she suggests, was part of a larger trend of devaluing the labor of writers altogether. Critics of the press have long warned about the corrupting influence of the fourth estate’s profit motive: A. J. Liebling once proclaimed that “the function of the press in society is to inform, but its role is to make money”—two forces that will always be at odds. But from our present vantage point it’s hard to disagree with Stone:

You don’t pay writers now because the culture has determined that intellectual contributions, aesthetic contributions are something that someone can do on the side, like a hobby. And see what happens to a culture who treats its artists and its intellectuals that way? Not good.

Changes in the city’s demographics also influenced the paper’s long-term prospects. In the view of Michael Tomasky, who wrote for the Voice in the 1990s, “the community of people who supported the Voice” had died by 1995, before it went free, because gentrification and real estate speculation had killed the soul of New York. “The whole idea of these rent-controlled flops that people could live in for cheap in the Village—that was all really disappearing by 1990,” he told Romano. It became difficult for the writers and artists who filled the paper’s pages, because “you started to need to be rich to live in the Village.”

Today writing as a profession can no longer promise even a hint of stability. Last year more than three thousand workers lost their jobs across broadcast, print, and digital news media. This past January alone, 538 more layoffs followed. The Internet must take part of the blame: if Facebook, Google, and Twitter hadn’t gobbled up ad revenue, the media business might not be on such unstable ground. But the industry was also forced into decline by broader economic pressures, as the American labor market grew increasingly subject to the demands of shortsighted investors and venture capitalists.

One of Menand’s insights about the Voice is that its “own success made it irresistible to buyers who imagined that they could do better with a business plan than its founders had done from desperation and instinct.” There is a kernel of optimism in his acknowledgment that sensibility is a crucial ingredient in a publication’s success—a fact that many buyers, especially the meddlesome ones, fail to understand. The Voice won loyal readers by cultivating a community-minded, risk-taking identity, opening its pages to engaged citizens, and letting its writers run wild. Its legacy can perhaps best be seen in the current wave of worker-owned publications—like the New York City–focused news outlet Hell Gate and the irreverent sports and culture site Defector—staffed by people jilted by corporate media. Outlets like these are betting on an idea for which the Voice long stood: that the making of a publication need not be optimized.