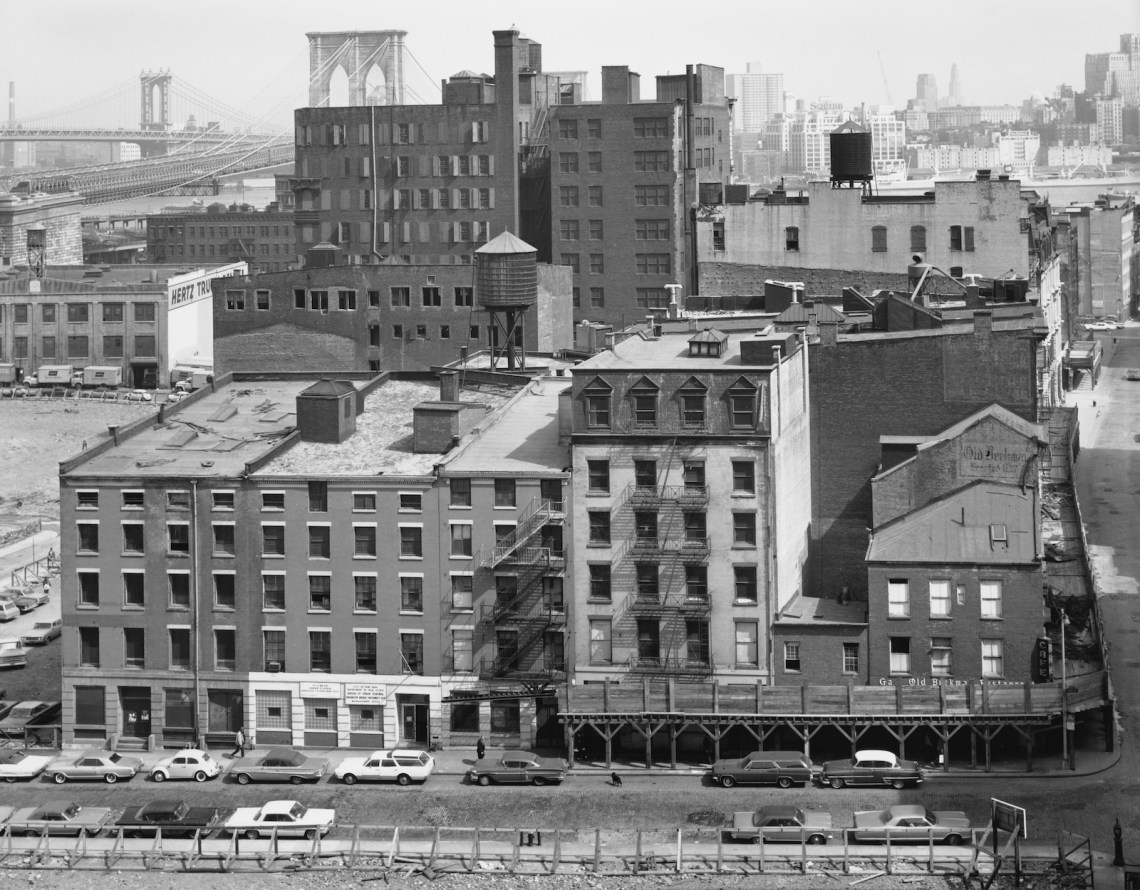

In the fall of 1966, when I was twenty-four, I returned to New York. I was finally completing the journey home I had begun when I left New Orleans in the winter of 1964. My friend, the sculptor Mark di Suvero, lived in a building on the corner of Fulton and Front Streets; I looked for a loft nearby. At the time very few people lived in Lower Manhattan. The financial district at the bottom of the island was filled with large office buildings; the place was deserted by five in the evening. Since hardly anyone lived there, there were no grocery stores or restaurants to speak of. Many streets were lined with four-story nineteenth-century commercial structures. The lofts above their street-level stores, previously used for storage, were often empty.

Artists rented them. I found mine a few blocks from Mark, a fourth-floor walkup above a jewelry store at the southeast corner of Beekman and William Streets. The rent was eighty dollars. It was what was called a commercial space, about four hundred square feet, with large dirty windows facing north and west, and illegal for living, the only amenity being a toilet. A painter I had meet at Max’s Kansas City, a kid named Tex, partitioned off a corner with sheetrock and two-by-fours, into which I put the darkroom table I’d dragged from New Orleans and then from Chicago. I traded him a few prints for the work. I found an overstuffed chair in the street, got it to the loft in Mark’s truck, and convinced Mark to help me wrestle it up the four flights of stairs. I found a desk out on the street. Other than that there were a couple of wooden Indonesian tea boxes I had taken from the port in New Orleans.

I had no idea what to do. I thought of myself as a photographer of people, but other than a few artists down near the water, there were very few people on the narrow streets where I now lived. I wondered what the story was, what wasn’t in the papers yet, what I could discover and make public.

One cold winter day Shirley Fisher, a PhD candidate I knew at the University of Chicago, brought over some peyote buttons. We ate them in the morning with cereal to cover the strong taste. Then we went out for a walk down near the Sailors’ Home, on the East River, near the tip of Manhattan. I had my Rolleiflex over my arm. A few blocks past Mark’s on Front Street we passed a building that was being demolished. I climbed inside to find that the door and roof had been removed to expose the old wooden beams. I turned the camera on its side, with the beams slicing across my square frame at a diagonal, lit by the bright sunlight coming in from the sky. It was an artsy picture, the kind I normally hated. Being stoned lowered my standards. Loading a Rolleiflex is a challenge for the sober. On peyote it was a nightmare. I sat in the corner of the snow-covered rubble and repeatedly tried to slip the paper of new roll into the slot of the roller. My fingers felt as if they were made of wood. It took a while.

The next morning I looked out my large soot-covered windows, north across Beekman. Glancing to the west I saw the missing buildings across the street. Buildings were being demolished all along my walk down to Mark’s place on Front. Fulton Street was a demolition zone. There were wooden barriers up on the south side of Beekman. Gray wooden police barriers stood before many of the buildings; others had all their windows tinned up. A light went on inside my skull: the story here was not about people. The Destruction of Lower Manhattan popped out whole from my peyote-fogged brain.

This was a historic place. The city had begun within a mile of where I lived and had grown north from there. Alexander Hamilton went to school at Kings College just a few blocks west, on the banks of the Hudson. His funeral passed under my window. Melville used the area for Redburn and “Bartleby, the Scrivener.” Suddenly the fields of broken bricks, the dust, the grime, the empty streets, and the tinned-up storefronts appeared the site of a historic event. They were demolishing Lower Manhattan. That was my story. All I had to do was make a picture of every building standing before they knocked it down.

*

Now and then during these months I would go up to the Magnum Photos office on West 47th Street, where Inge Bondi encouraged me to apply for funding to the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA). I had never received any grant for my photography, and I was still convinced that if what I did was any kind of assignment—if I was paid to do it—it wouldn’t be my own. Nevertheless I went to see Inge’s friend, Allon Schoener, a friendly middle-aged man who sat behind a large desk in a small office in Midtown. I suggested he fund me to ride my motorcycle around the city, photographing mirror shops. He was mute. How about me photographing the Lower East Side, or taking color pictures of the subway? Nothing. Then I finally said, “How about the destruction of Lower Manhattan? They’re knocking all the buildings down.”

Advertisement

“How much money do you want?” he asked.

True to his word, Allon secured me a small NYSCA grant. I believe it was the first year they funded individual artists. I got $4,000. My workhorses until then had been my 35mm Nikon F Reflexes, an awesome camera for photographing people, especially people in motion. But these were buildings. All they did was stand there. From what the curator Hugh Edwards had showed me at the Art Institute of Chicago, I was aware of large-format cameras. I was also a great admirer of Walker Evans, much of whose work was of architecture.

I heard that Oldens, the big camera center up on 32nd Street, was trading equipment for prints. I picked the least expensive view camera they sold, a Calumet, with a four-by-five-inch glass plate in the back. The front had a plate to slide in a lens. I traded some of my prints from my series The Bikeriders for two of the lenses. The first was 75mm, the second a little shorter, for interiors.

The very first exposure I made with a camera that I knew almost nothing about would appear as plate sixty-six in The Destruction of Lower Manhattan. It was of 100 Gold Street, sitting on a sea of rubble, with the new skeleton of the ramp to the Brooklyn Bridge behind it. The demolition men used jackhammers to destroy it and torches to cut the rebar. Most of the commercial brick buildings could be taken down in four or five days. 100 Gold Street, the former FBI building, made from hand-mixed reinforced concrete, took six months.

I used to head over to the building on weekends, climb over a wooden barrier, walk across the rubble, and then climb in through a window. With my Rolleiflex on an aluminum tripod, I would sit on the empty windowsills of the upper stories, where snow had blown in onto the floors, taking pictures of myself looking out at the ruins below.

I had crossed paths with the demolition men a few times and soon learned to keep my distance. When I reached the tenth floor of 100 Gold that first Sunday, I knew I didn’t belong there. This was their place. Coffee cups, sandwich wrappers, and some old soda cans lay on the cement floor. Since the two stories above had been removed, the floor I had reached was now the roof. Next to a pile of snow was a small bulldozer, a Cat. I was afraid to go in their headquarters, which I could see from my loft.

Eventually I got bored photographing buildings and empty rooms and wanted to do what I did best, photograph people—in this case the men who tore the buildings apart. The guy I was most afraid of was the foreman of the East Side crew, an ex-marine named Dominic. That was Dominic’s Cat bulldozer up at 100 Gold Street, his coffee cups. During the months it took him to demolish the building, it broke his arm.

One day I got up my courage and walked into the demolition men’s headquarters to show them my permission letter from the NYSCA. Huey, one of the foremen, took a look at it. Then I showed it to Dominic, saying I was making pictures of the buildings. He looked right at me and said, “I don’t give a shit what your letter says. If you come near one of my buildings I’m going to drop a wall on you.” He also wanted to know why I had a “fuckin’ camera over my shoulder and not a gun.”

Eventually, by giving out pictures, I befriended him. Dominic was a World War II veteran who had been at the Battle of Tarawa. Intelligence had said the tide would be high enough for the landing crafts to approach the island, but it was so low that many of the boats got stuck on the coral far from shore. The Japanese defenders raked the poor men with machine guns and artillery. A thousand marines were killed there in a few hours. Dominic’s brother died in his arms.

Advertisement

*

In my darkroom I would remove a plate from the film holder, place a single sheet of four-by-five-inch Tri-X film inside, replace the plate, flip the holder over, and repeat the process on the other side. Out in the field, in the middle of the street or a lot strewn with broken red brick, I would set up my aluminum tripod. Then I would use what was called “the asshole screw” to set the camera onto a plate on top. I would pull a black cloth over my head, weighted so that the wind didn’t blow it, at which point I would see, upside down and reversed, the image of the building. Then there was the parallax error. Because I was standing before a high structure, the top of the building looked narrower than the base. To correct this, I’d adjust the tilts on either side of the lens, which moved the lens in relation to the film plate in the back. Then I’d remove the plate that covered the film, release the shutter with a short cable, and replace the plate. I was done. I’d made a photograph.

Any dust or dirt inside the holder would show up as big black dots on the negative. My locations—uncleaned for years, missing windows—could not have been dirtier; I was covered in filth every day. My arms, pants, shirt, face, and beard looked like I’d just returned from employment as a chimney sweep. After myriad errors I mastered the technique of loading my four-by-five film holders and marched out each day, wearing my black sheet like a cloak, my camera and tripod over my shoulder like a gun.

I tried to make a decent picture of each building. Back in my loft I put up my small eight-by-ten prints of the buildings in a line, to recreate an entire block. A second vast demolition site existed on the West Side, including the future site of the World Trade Center (eight acres) and all of Washington Market (four times larger). West Street, at the very edge of Manhattan, ran beneath what was left of the West Side Highway, which was also being demolished block-by-block.

Sunday mornings were a good time to work, with the least traffic, which gave me the longest intervals, since I often made my pictures from the middle of the street. If I saw a car approaching I had to grab the tripod and camera and jump out of the way. I took almost all the pictures on weekends and holidays. I didn’t want cars parked in the streets because they obstructed my view of the buildings and destroyed the pretense that my pictures were made in the nineteenth century. One time I set up on the narrow walkway of the Manhattan Bridge, which at the time had almost no pedestrians. Every now and then someone would lean out the window of a passing car and yell, “Go ahead, jump!”

The condemned buildings were city property. They were maintained by men in green uniforms from the Department of Urban Renewal, practically all of them either African American or Puerto Rican. I made portraits of them and gave them prints. In return they gave me the key to the same padlock used on all the buildings. “Just make sure you take the lock inside with you,” one of them said. Now I no longer had to climb in through missing or broken windows. In the nineteenth century commercial buildings were linked. Once you were inside one, you could go up the stairs, if it had stairs, then climb out onto the roof and climb down into the next building, and enter every building on the block.

The buildings were full of things abandoned by the tenants as they rushed to leave. On the west side I entered what was once known as “Printers Row.” Inside one printer’s loft I picked up off the floor a small blue leather-bound book with blank pages. I also fell through the stairs that same day. I know this because, back in my loft, I wrote about it on the blank pages of the printer’s book, which became my first diary, a habit I would keep up for decades.

One afternoon the NYPD interrupted me as I was making a self-portrait inside the abandoned Susquehanna Hotel downtown, on West Street. The room I was in had a bed, bureau, mirror, and dishes out on a counter, all covered by a thick layer of soot and plaster. The roof was falling into the kitchen. I was sitting there wearing my black shroud, staring at my Calumet on its tripod, when a police officer walked by my room, looked in, and said, “What? You live there?”

The truth is that the buildings that were in the process of being demolished were extremely dangerous to be inside. Walls had holes, doors were missing, stairs had no planks across them, and I was walking around them on the weekends. If I fell through to the floors below, no one would even know about it until Monday, when the demo guys returned to pull apart the rest of the structure. Or no one would come at all.

Allon Schoener had given me the money because he liked to do photo exhibits. (In 1969 he would go on to create the ill-fated exhibition Harlem on my Mind at the Metropolitan Museum.) Two years after I made them, he insisted on exhibiting my pictures inside an abandoned brick-walled storefront in the fish market, kitty-corner from the north side of Mark’s building. Outside the “gallery” they hung a huge banner that read THE DESTRUCTION OF LOWER MANHATTAN. Visiting Mark one day, he took me to his windows and sat down on a ledge looking north to the fish market. “You see that?” he said with great seriousness, pointing towards the banner. I did. “You ruined the neighborhood.”