In response to:

A Bad Deal that May Not Work from the November 30, 1972 issue

To the Editors:

I returned from North Vietnam in mid-November puzzled to find so many antiwar activists, especially intellectuals, expressing the cynicism summarized by I. F. Stone in your November 30 issue.

Stone’s great power lies in uncovering facts unpleasant to the Pentagon and Administration; he rarely attempts to analyze the revolutionary process, or the climate of questioning, that give his facts their relevance. It is typical that he approaches the Vietnam question within the framework of the very “great power” assumptions he rightly despises. The draft Peace Agreement between the US and North Vietnam is seen as a “bad deal” resulting from a “tight squeeze” on Hanoi due to the “détente” between Washington, Moscow, and Peking. It would be more realistic and balanced to view the Peace Agreement within the framework of the situation in Vietnam itself, assuming that the concrete realities there are more important than any relationships between the “great powers.” Viewed this way, the Agreement is a compromise, part of a long process of eliminating the US grip on Saigon. Since it is not possible to physically drive the US out of Vietnam (as the carriers and Thailand bases prove), the question is whether the Peace Agreement is a favorable step forward for the Vietnamese resistance against the US policy of intervention.

Stone is unconvincing in his claim that the Peace Agreement is a regression from the 1954 Geneva Accords and from what the Vietnamese would have obtained through Nixon’s “Eight Points” of February, 1972. The Geneva Agreement did not fix a date for elections as Stone claims; it only specified that elections should come no later than June, 1956. The present Agreement calls for elections “within three months after the ceasefire comes into effect.” Neither was Geneva any clearer about political prisoners: it provided for their release within thirty days while the present Agreement, no matter how Kissinger interprets it, specifies that “all captured and detained personnel” shall be released during the proposed sixty-day US troop withdrawal. Where the current Agreement is a decided improvement on Geneva is in its recognition of the Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG) as a legitimate administration with a right to maintain armed forces on its territory. Geneva did not recognize the Vietminh as a political entity in South Vietnam and forced the regroupment of its military forces north of the 17th Parallel, thus leaving millions of South Vietnamese defenseless against the Diem reign of terror (1955-1959).

The Peace Agreement is an improvement over Nixon’s February offer for much the same reasons. Nixon’s prior proposal claimed legitimacy for the “constitutional” process of Saigon, aimed at maintaining that legitimacy in all areas of South Vietnam, would have reduced PRG personnel into the category of “political forces,” demanded a withdrawal of North Vietnamese troops from the South, and promised American military withdrawal within six months of an agreement (thus American troops would have remained during the election process). The new Agreement accepts the PRG as a legitimate administration, allows its troops to remain in position, creates a three-part administration (not a coalition government but more than Nixon’s vague “electoral commission”) to carry out elections. Most important, American bombing and shelling would end, and American troops would be withdrawn before the new elections to set up a southern government.

Thus the Agreement seems far more favorable to North Vietnam and the PRG than Stone notices. But Western words on paper, as he rightly notes, are hardly ever carried out in Indochina. One would think that the Vietnamese revolutionaries, with their history of betrayed peace agreements, would know this better than anyone, and would hardly need it pointed out by I. F. Stone. The question Stone should ask is: why do the Vietnamese, who after all drafted the Agreement themselves, think it is favorable? Apart from the principles of US military withdrawal and self-determination for South Vietnam, the answer lies in an estimate of the balance of forces in Vietnam itself.

Since April 30 the Vietnamese have been waging what they call an offensive on three fronts: military, political, and diplomatic. The Peace Agreement has to be viewed as the diplomatic front of this offensive, not as a last-ditch proposal arising out of failures on the battlefield. The aim of the offensive has been to destroy the option of “Vietnamization” and make the US accept a negotiated withdrawal. This offensive has succeeded militarily, with the collapse of most of Saigon’s conventional army, and politically, with the increasing isolation of Thieu and economic disaster in Saigon. Their diplomatic initiative has given the PRG and North Vietnamese the political advantage of standing for peace, probably the most passionate desire of the South Vietnamese in cities under Thieu’s control. The Agreement thus becomes a political-diplomatic instrument in the struggle to overthrow Thieu’s military regime.

As Pham Van Dong told Newsweek in the first hint at the Agreement (October 30): “Thieu has been overtaken by events. And events are now following their own course.”

It was prophetic of the New York Times’s Craig Whitney to have written on September 24, in summarizing the military results of the offensive, that a ceasefire would only be possible through a US “concession of large parts of occupied territory” to the other side. This Whitney did not expect because “if the North Vietnamese and NLF offered such a device, it would be out of self-confidence not out of weakness….” Whitney’s article pointed out that Saigon’s army was half-shattered, beginning with the Third Division at Quang Tri, the Twenty-second (Kontum), Fifth (An Loc), Twenty-first (Highway 13), First (Hue), and Second (Que Son). Since then, the only remaining combat-seasoned divisions, one paratrooper and one marine, have taken casualties ranging as high as 300 dead per week in futile sweeps through Quang Tri. According to Whitney, one million refugees have been created in the fighting since May, destroying the “pacification” and other “security” programs of the US-Saigon administration. And, according to the Kennedy Senate subcommittee, many of these refugees are returning to their ancestral homes in PRG-controlled areas.

The effect on Saigon is devastating. The roads to and from the food-growing areas are under guerrilla control more than ever. The economy, spiralling downward as US personnel leave with their dollars, is in “paralysis” due to the saving and hoarding taking place during the offensive (Washington Post, September 3). A crucial effect on army morale, according to the October 20 Chicago Daily News: “Since talk of peace began two months ago, desertions in the South Vietnamese army increased 50 percent. Presently, 20,000 soldiers are going each month.”

During the presumed period of secret talks between Kissinger and the Vietnamese this fall, the offensive never faltered. In fact, the highest US intelligence experts were reported in the September 12 Times as acknowledging that “Hanoi can sustain the fighting in South Vietnam at the present rate for another two years.” The same source cited the “highest number of regular troops in the Mekong Delta…since the start of the war,” nearly all appearing there since the start of the 1972 offensive.

Seen as part of the offensive, the Peace Agreement makes sense. It is possible to modify the form of what is proposed for the South from an immediate coalition government to one of dual administrations leading to a new government, because Thieu and “Vietnamization” are a significantly weakened threat to the peace. The strategic defeat of “Vietnamization” means that the Saigon army has been proven incompetent, and is only propped up by the unprecedented bombing and shelling which the Peace Agreements would end. Once the Agreements are signed, Thieu’s army will be no match for its revolutionary adversaries. The US cannot have what it has wanted: US withdrawal plus Vietnamization, a Korea-type solution to the Vietnam question. The US can only have withdrawal plus a second-class Vietnamization: a face-saving “peace with honor.”

For the Vietnamese the Agreement is very important for two further reasons: First, it suggests political struggle as the only method for “winning” the cities where over three million people of mixed political sympathies reside. Not only would military force be useless in winning such a battle, but experience has shown that attacks on cities are met by saturation bombing. Political insurrections are nearly impossible in cities also as long as Thieu’s police, backed by the full commitment of the US, can crush the slightest activity. But what will be the morale of these police when the US leaves? Temporary savagery at most (which is why Americans must show immediate concern at the plight of political prisoners in Thieu’s jails), but certain disintegration if they provoke their enemies at Saigon’s borders.

Of course, the war can continue. I share I. F. Stone’s absolute skepticism toward the US willingness to sign the present Agreements or implement them later. But here is the second reason the Agreement is so important to the Vietnamese: it not only would end the present American killing for the moment, but would also put the US on weaker political and military ground than ever before. The US can supply Saigon and send in “civilian advisers” by the thousands but this is not 1955. How are the Saigon army and US “advisers” going to be more successful than 500,000 American ground troops, 200 B-52s, 50 destroyers, and seven aircraft carriers? And if the US chooses to re-escalate with more bombing in the future, it can do so but only at a greater disadvantage than now. If not destined to be the basis of final peace, then the Agreement will be a strong political basis for continued struggle by the Vietnamese for peace and self-determination in the future.

And what of the “great powers”? They are part of this context but in a way quite different from the world of I. F. Stone. Suppose that by inviting Nixon to a summit, China diverted attention from the PRG’s Seven Point Peace Proposal of July, 1971, by raising hopes of a settlement in Peking. Suppose further that in accepting Nixon this May, Moscow assured his reelection and permitted the bombing escalation to go unchecked. Even if both are true, these “great power” moves did not prevent Vietnam from carrying out its longest offensive of the war and continuing to receive material aid from both the Soviet Union and China.

What Stone underestimates is how much Kissinger’s attempt to play Godfather has failed. It has not been without a great degree of success, perhaps most notably in confusing the American public, but it has not triumphed over Vietnam. What the Vietnamese are fighting for is just as universal as the empire Kissinger is trying to extend by his manipulations: the Vietnamese believe this is the age when small countries and cultures can make revolution and have independence essentially through their own efforts. While Kissinger was tripping to Moscow and Peking, the PRG was being seated at the conference of sixty Non-Aligned Nations in Guyana this summer: one international event highly publicized here, the other invisible but perhaps more important in the long run.

The principles for which the Vietnamese stand surely will not triumph by some automatic process of history. They are shedding their blood this very minute to make these principles a reality. Instead of being cynical about the outcome, we in America should realize that our interests too are violated by Kissinger’s concept of empire. It is a system of open space for expanding corporations, for covert military operations against revolutionary and nationalist movements, and in the end it takes away our power to affect foreign policy or use our taxes for anything but military-related purposes. To continue the antiwar movement is to continue a struggle for our own independence against a system which destroys as ably with deceit as it does with bombs. We should be pressuring for the Agreement to be signed and implemented, working in a closer way with the people of Indochina (through programs such as Medical Aid to Indochina), learning and teaching others the lessons of this war so as to be ready to resist future re-intervention in Vietnam or new Vietnams elsewhere in the world.

Tom Hayden

Roros, Norway

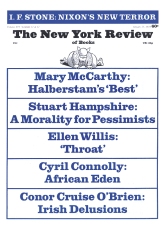

This Issue

January 25, 1973