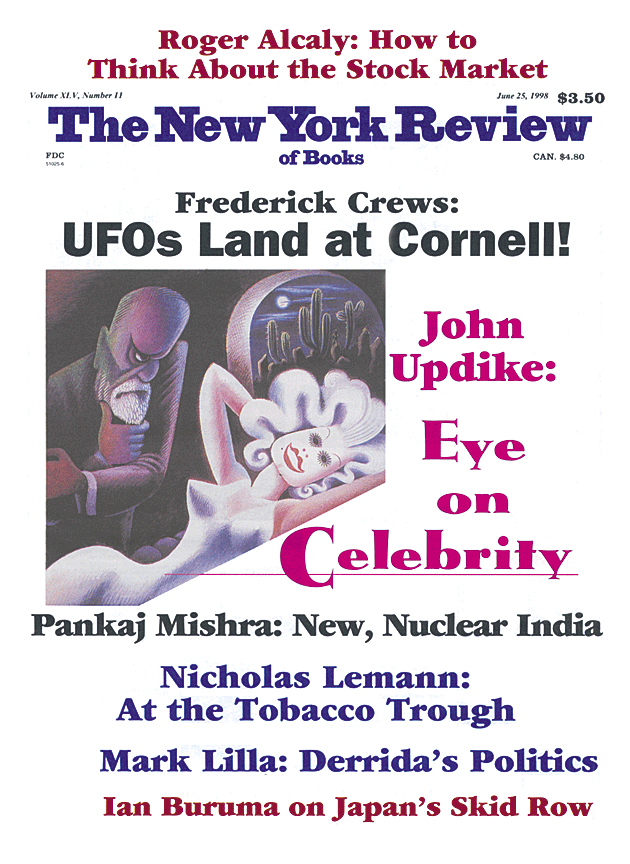

A caricature can be a beautiful thing; the ambitious, ingenious, and slightly anxious exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, Celebrity Caricature in America, emphasizes the sociology of celebrity, and mingles the remarkably beautiful work of Al Frueh, Miguel Covarrubias, Ralph Barton, and William Auerbach-Levy with that of a score of artists a shade or two less absolute to produce a plethora. Everything is done to make the show intelligible and appealing to the multitudes who never heard Caruso sing, followed Babe Ruth’s exploits, saw John Barrymore in a play or Mae West in a movie.

The first rooms are piped with jazzy, Astairish music from the entre-deux-guerres era, when celebrity is supposed to have ripened into its modern form; photographs of those caricatured are helpfully placed high on the walls; a corner of Sardi’s lined with framed caricatures is reconstructed; the back rooms are enlivened by some continuously running cartoons from the 1930s by the Disney and Warner Brothers studios, in which animated caricatures of film stars consort with the likes of Donald Duck and Bugs Bunny.

As a child who went to the movies with his parents at the age of three and was empowered to go alone to the neighborhood theater from the age of six, I found the cartoons—seen again after a gap of sixty years—a thrilling return of lost vistas. But my cultural horizon fell short of such early-twentieth-century theatrical figures as Donald Brian, Julia Marlowe, John Drew, and Raymond Hitchcock; nevertheless I could admire the beautiful economy of Al Frueh’s renderings of their once wildly recognized countenances. A celebration of celebrity turns out to be, with enough lapsed time, a demonstration of celebrity’s impermanence—a melancholy study in our essential obscurity. The subject of the caricature sooner or later melts away, leaving us, as with Tutankhamen or Ozymandias, or as with the judges drawn by Daumier and the cabaret performers caricatured by Toulouse-Lautrec, the art only. Art has the capacity to outlast fame, though the artist in life must bow to the famous.

It was the happy fate of several periodicals relatively early in the century, foremost the Vanity Fair that ceased publication in 1936, to publish caricatures of extraordinary merit. A very young Mexican, Miguel Covarrubias—who later went on to become a leading archaeologist, ethnologist, and folklorist in his native country, and to die young at fifty-three—lifted caricature, in the Vanity Fair of the Twenties and Thirties, onto a new plane, though of course he had predecessors and near-equal rivals. The Italian Paolo Garretto, cleverly using airbrush and paper cutouts, produced Vanity Fair covers and illustrations of arresting simplicity and stylistic daring; his exuberant 1934 gouache of Al Smith is the Washington show’s signature piece, and his streamlined representations of Thirties “strong men,” from Mussolini and Hitler to Gandhi and La Guardia, form a historical record of sorts. But compared to Covarrubias he is a mere toymaker; he had little of the Mexican’s painterly qualities or his curious primitive force. Ralph Barton, a very different but equally brilliant caricaturist, wrote that Covarrubias’s caricatures are “bald and crude and devoid of nonsense, like a mountain or a baby.” Crude, surely, only in the sense that perfectly realized images gain a certain starkness, but indeed combining a mountainous largeness with a tenderness, an innocence of vision that might be called infantile.

Covarrubias admired the murals of Orozco and had the advantage of a strong Mexican tradition of political, pamphleteering caricature. Reaves points out, in her catalog, that Covarrubias’s caricatures of American celebrities are much less savage and grotesque than those of his fellow country-men, Xavier Algara and José Juan Tablada. “Covarrubias had adapted to the Vanity Fair aura,” Reaves writes. “This was Mexican caricature in evening clothes…. For a lesser artist this emotional distancing and refinement could have resulted in amiable banality. For Covarrubias, it freed him to concentrate with cool detachment on likeness, line, and pattern.”

In black and white, Covarrubias favored a woodcut look, with a toothlike shading of short tapered lines. In his 1925 drawing of the young Irving Berlin, these lines round into prominence the great lidded eyes, with their oily-black irises. Douglas Fairbanks is reduced to a continuous arabesque of eyebrow, eyes as far apart as a frog’s, hair as slicked as a coat of paint, and a mustache and upper lip symmetrically working to bare a fine set of teeth; what startles us in 1998 is how effectively Covarrubias conveys in a few stylized lines Fairbank’s courtly thrust, a lower lip and cigarette-holding hand coming forward to assert a type of vanished, braying, charmingly formalized masculinity. The caricature of Paul Whiteman is graphically interesting in containing a little cubistic explosion in the center of the subject’s mostly empty ovoid face; this is one of the most abstract of Covarrubias’s American caricatures, and one of the less friendly, but a joy to ponder in its Art Deco elegance.

Advertisement

After 1930, when improvements in the Condé Nast presses and photoengraving processes made possible frequent use of color, Covarrubias displayed a lively palette, contrasting, in illustrations for Corey Ford’s “Impossible Interviews” series, a nude Sally Rand’s lovely skin tint, golden curls, and pink feather-fans with Martha Graham’s greenish flesh and angular red dress; and the Prince of Wales’s English tweeds and pallor with Clark Gable’s California white flannels, turtleneck, and tan. The Prince of Wales, as rendered in 1932, is a prophetic character study in shifty, spoiled-looking diffidence.

As far as my memory of celebrity went, Covarrubias’s likenesses seemed excellent, and where memory drew a blank, as with the caricature of Eva Le Gallienne, the sense of a real person was conveyed, not only in the tilt of the features but in a certain spiritual aura provided by the coloring and a usually vivacious pictorial dynamic. Covarrubias’s blend of witty linear likeness and painterly quality was uniquely his; Frueh, Barton, and Al Hirschfeld did linear caricature, and Will Cotton, a painter from Newport who broke into Vanity Fair when color came in and who was doing New Yorker covers up through the 1950s, did rich pastels whose satiric edge was benignly fuzzy—though he did the definitive rendering of Jed Harris’s five-o’clock shadow, and skewered Nicholas Murray Butler’s pink owlishness.

Of the artists I especially cherished in the show, Al Frueh was the oldest. Born in Lima, Ohio, in 1880, he came to caricature, he claimed, by way of trying to learn Pitman’s shorthand method, and elaborating the squiggles. His early newspaper work showed acquaintance with French and German caricaturists, and during travels in Europe in 1908 and 1909 he studied briefly with Matisse. His linear economy was marvelous. Alla Nazimova’s body becomes one thick line indented by hands and topped by a face (circa 1910-1912). He drew George M. Cohan without a face, as all stance and gesture, and Marie Dressler—the bulky comedienne of many silent films—as all face, wide and furious, mounted on a body of five curved lines.

Always a lover and caricaturist of the stage, Frueh moved from the old Life to The New Yorker when it started up in 1925, and kept his place on the theater page until the 1960s, when the fashion for caricatures had long passed. He scattered his uncannily concise likenesses in a rectangle of rather arbitrary space, and worked, I remember learning with astonishment, entirely from memory, after seeing the performance. It is one thing to remember, say, that Katharine Cornell had a wide face and long eyes, but to do justice to her nostrils, and fit them to her upper lip, is quite another. The Fruehs on exhibit, mostly gifts from his children, favor the early works, produced on brown-tinted board with ink and white highlights; they were originally not reproduced but displayed, in Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 gallery. Frueh’s gift for a concise linear likeness displays one aspect of the caricaturist’s art at its peak, as fluent as handwriting.

Hirschfeld, still miraculously practicing into his nineties, is Frueh’s prime heir, and a titan of his trade. However, in his wiry pen-and-ink drawings the line becomes abstractly active in a way Frueh’s did not, with a consequent flattening, sometimes, of our impression. Spiraling eyes, ears containing x’s, and hair containing a trio of NINA’s weaken our sense that this antic penmanship is holding a real person up to the light. A 1950 black-and-white caricature of Walter Winchell shows Hirschfeld still with some bite, and a 1956 cover of Edward R. Murrow for TV Guide—one of the last magazines to foreground caricature—reveals how handsomely he could function in color and three dimensions.

Ralph Barton had no third dimension, but in the two he used he was an angel of invention, ease, and effrontery. His wandering line was simultaneously precise and carefree; and it was apparently tireless. Examine any of his famous composites—the reproduction of the massive curtain full of celebrated theatergoers he designed for the stage of the Chauve-Souris, or “Bat Theater”; the huge composite of Hollywood celebrities dining at the Cocoanut Grove; the slightly less numerous groups he did for Vanity Fair—and every face bears scrutiny; each is alive and individual.

His theater cartoons for Judge, Life, and the young New Yorker marry the extravagant with the exquisite; I stood before his drawing of Ed Wynn and Richard B. Harrison and marveled at one of the long curves, a fine charcoal-pencil line drawn freehand with the precision of a machine. Barton’s control over the implements of his trade had a betranced finesse; though he was overwhelmed by magazine commissions, often working around the clock, there was never a loose line or a carelessly applied spot of wash. A splendid caricature of Leopold Stokowski, of 1931, uses an encircling wet on wet dark wash to define the conductor’s sphere of fuzzy white hair; his impossibly supple and slender Billie Burke wears a tint of wash as even as it is delicate. And how definitively he captures her celebrated simpering profile, spotlit in long-darkened Broadway shows but still visible in the guise of the good witch Glinda, in the movie of The Wizard of Oz. Leaning into a Barton drawing, we feel acrobatic ourselves, involved in breathtaking acts of balance and daredevil swoop.

Advertisement

A Francophile and depressive, needing always to travel or change apartments, Barton tried to break out of two dimensions, writing theater notices and two small books, one of light verse and the other a travesty history of the United States. Their critical reception was cool; unlike Beerbohm, he was a graphic artist purely. His depression deepened; his behavior became as erratic as his perspective. At the end he felt he was still hopelessly in love with his third wife, who had become Eugene O’Neill’s third wife. In 1931, just short of his fortieth birthday, he shot himself in the head, leaving behind a suicide note diagnosing himself as a manic-depressive and saying that for three years he had not been “getting anything like the full value out of my talent.” Relatively few of the hundreds and hundreds of his drawings exist as originals; they were submitted to the reproduction processes of the time, which could not do justice to his beautifully graded washes, and then destroyed. Such was the common fate of commercial art in the age of metal photoengraving; it was never thought to be headed for museum walls. So museums display what they have.

William Auerbach-Levy, born in Russia, preferred to work with a brush and to draw from the life, during visits his subjects paid to his studio. He wrote a delightful book, Is That Me?, describing the process whereby he caught the likenesses of such as Jimmy Durante, Ring Lardner, and Eugene O’Neill. He was capable of great simplification; he drew Lardner without a nose and O’Neill without eyes, and several of his drawings—of Mencken, Alexander Woollcott, George Gershwin, Franklin P. Adams—became virtual trademarks, succinct images in black and white sturdy enough to serve on stationery, napkins, the backs of playing cards, and the like for their celebrity subjects. The show includes some of these much-reproduced heads, and it is interesting to see how much whiteout he used to adjust, say, the few stark lines of the Adams drawing—only the final reproduced image looked effortless and inevitable.

It is interesting, too, to compare Auerbach-Levy’s head of Mencken with the much more innocent and contrived image Hirschfeld produced for the cover of Collier’s in 1949. By then Mencken, with his cigar and central parting, had become a harmless icon, a famous old fogey, but Auerbach-Levy in 1925 brought out the man’s strength and menace—the ominous weight of his head, and the dangerous sneer on his lips. One can see on the original of the Woollcott that the hair and the curve of the head had been sketched but not inked in; the few lines of the face, with the incompleted circles of the glasses, are far more effective in disembodied isolation.

The good caricaturist has the rare gift of bringing forth from the face’s knit of flesh-knots, and the spaces between them, the live spark of a unique identity. In the making of a succinct but convincing likeness, with resonances beyond the comic, Auerbach-Levy was unequaled. He had another mode, in which the caricatural element was minimized to the point of a straight portrait. A yellow-faced Noel Coward seen by a red-curtained window giving on the Brooklyn Bridge, the Shubert brothers as comic and tragic masks—in these the brush declares itself in halftones and small flourishes, and we are near the end of caricature as an audacious simplification. Few besides me remember, I suppose, Auerbach-Levy’s weekly portraits, in wartime Collier’s, of our allies and collaborators in World War II, following after Sam Berryman’s hideous and hilarious series of our atrocious and absurd enemies. It was a task that now would be entrusted to photographs, even cloudy ones.

Reaves in prefacing her catalog says, “Caricature did not vanish after World War II, but this form of it—focused on personality and fame rather than social and political satire—diminished or changed its emphasis.” One can theorize considerably on the nature of celebrity and personality and the kind of artistic attention they receive. Did Fifties conformity dampen caricature? Had the triumph of photography made us impatient with any other sort of representational image? Did the decline of the Hollywood studio system, of celebrity-driven radio, of Broadway, of café society deprive us of the fixed firmament of stars caricature had thrived on?

Vanity Fair, the grand sponsor of the art, was ingloriously folded into Vogue in 1936, and has been reborn as a glossy scandal mag. What do we make of that? Well, it does seem that on the largest, grandest scale what we admire in other human beings undergoes a gradual shift. Saints and kings and nobles were once highly esteemed, for their touch of the divine. The nineteenth century made celebrities of clergymen, millionaires, humanitarians, and opera singers. A conflux of media—radio and movies and a still-thriving popular press—created the array of theater types, with additions from sports, the arts, and academia, that forms the basis of Celebrity Caricature. This pantheon was loved so much in its imaginary assembly that a cloth manufacturer made a silk print of Barton’s Cocoanut Grove tableau and at least one young flapper fashioned it into a dress, which is displayed with its (to me invisible) party stains still on it. What has happened since? Rock stars, who are already caricatures, and television and film performers with more than a tinge of the interchangeable. Easier to caricature Clark Gable than Brad Pitt, or so it seems.

Of course, caricature, like light verse, goes on. Al Hirschfeld goes on, and readers of this journal for thirty years have been entertained and enlightened by David Levine’s cross-hatched homunculi. There is Gerald Scarfe, for those who like to see a lot of ink spilled. What happened to caricature between 1910 and 1950 was perhaps as simple—and as tautological—as the presence of a market for it, as long as the magazine world thrived. And modern art happened to it. The fin-de-siècle impulse of a new liveliness came out of Paris. Cubism and muralistic expressionism inspired Covarrubias; expressionistic distortion and surrealistic playfulness loosened up Barton. An audience able to appreciate subtle and dashing work existed. The Twenties’ culture consumers were light-hearted but not empty-headed. Certain formal principles still haunted the popular expectations of art; anatomy and perspective were still taught in art schools and valued by art editors. The appetite for aesthetically intricate caricature and the artists who could satisfy it rose and faded together. People are dimmer than they used to be.

This Issue

June 25, 1998