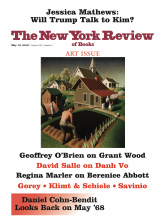

The art of Danh Vo is popular and politically engaged, though it’s the opposite of agitprop. Vo is too canny and too much of an aesthete for that. He’s like Prospero and Ariel both, light on his feet, and his art manifests images and pulls in references from disparate places; it feels in transit, as if it just alighted here. The work can be profane, caustic, irreverent, or elegiac, often in combination. It can be beautiful or visually negligible. Occasionally it can be dull. Vo is already widely celebrated in Europe, but the retrospective “Danh Vo: Take My Breath Away” at the Guggenheim Museum is his first major show in this country.

Vo makes art by taking objects from the world—a washing machine, a chandelier, a car engine, a pen nib—and bringing them, sometimes with minimal alteration or none at all, into the museum. As an idea, this is certainly not new, but to assume that Vo’s work has anything to do with Marcel Duchamp’s readymades strikes me as wrong. The impulse is different. Duchamp’s snow shovel and bottle rack are anonymous and semi-ironic, idiotic even, in that amusing Dada way. Vo’s objects are, for the most part, highly specific; they are the visual equivalent of poetry’s “objective correlative.” Everything in Vo’s art comes with a story; his objects point to the way that things close to us—a signet ring, a marriage contract, or very ordinary things, like a cardboard box—are embedded in a web of connections with the larger world.

For example, Das Beste oder Nichts (The Best or Nothing, 2010) is a car engine, a hunk of soot- and rust-stained metal, albeit with an interesting, faintly intestinal or bestial form, until you learn that it was exhumed from the Mercedes taxi that belonged to Vo’s father, which symbolized for him, as for many other immigrants, having made it in the West. If you were just to hear about the piece, it might sound sophomoric. But on the floor of the Guggenheim the engine is strangely arresting; it looks like the carcass of an animal, something prehistoric, perhaps a deep-sea creature that has become petrified. Like a lot of Vo’s work, it has a How did that get here? quality. It doesn’t happen every time, but there is an aesthetic transference that can occur at the level of display. His best work refers to more than one thing, and even though transparent by design, still retains some mystery that can’t be easily explained.

Vo has a remarkable personal history, and it has given him a rich vein of material. He was born in South Vietnam in 1975, shortly after the end of the Vietnam War. In 1979, he and his family fled the country in an unseaworthy boat, somehow hoping to get to the US. They were picked up by a Danish freighter in the South China Sea, and after a layover in a refugee camp, they eventually made their way to Denmark. Vo went to Danish schools and was admitted to the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, where he was discouraged by the faculty from painting. A visiting professor, Rirkrit Tiravanija, a well-regarded practitioner of a type of conceptual art known as relational aesthetics, noticed him and arranged for him to attend the more happening Städelschule in Frankfurt.

Vo was a quick study, and seems always to have had the knack of attracting mentors and supporters. Something about “the way we make art now” aligned with how his mind works, and the new freedoms in art—the permission to take anything from anywhere, to make out of any object or circumstance a kind of thought bubble—opened up a space for his personal complexities to land. Like most artists, Vo is an amalgam of several different impulses and skills distilled into one sensibility: the archivist and scribe, the designer/arranger, the fashion stylist, the cultural critic, the megalomaniac and artful dodger.

Some of Vo’s themes are personal, like the Asian refugee and emigrant, the good son and gay man; and others are global: postcolonialism, the dislocations of war and the technocratic arrogance of which it is the result, religion, capitalist imperialism, and the law of unintended consequences. In some of Vo’s work the themes are refracted, one inside another; the micro in the macro. At times the ideas are overmatched to their correlative; the work can feel a little top-heavy.

In the Guggenheim, with the rhythm of its bays and the concentrated engagement they encourage, Vo’s tableaux and objects from life, and his elegant and precisely executed deconstructions and recombinings of sculptural artifacts from different times and cultures, have the aura of sophisticated stage design. The experience of seeing his work is like being in the theater for a much-anticipated production when the curtain first goes up—there is some of the same hushed expectation.

Advertisement

One of Vo’s best-known sculptures (16:32, 26.05, from 2009) involves three nineteenth-century crystal chandeliers that originally hung in the ballroom of the Hotel Majestic in Paris. The largest one was left intact and hangs from the ceiling. One is largely dismantled; its strings of lights and crystals are spread out on the floor, and it makes a ghostly, mournful image. A third, smaller chandelier hangs inside a wooden shipping container, looking disconsolate in its confinement.

Crystals strung along broad, sweeping catenaries, chandeliers in art are usually meant to signify fragility and opulence, like a spray of champagne suspended in the air. Vo’s chandeliers are not especially graceful or pristine; their brass arabesques droop; they look a bit tired. What distinguishes them is their supporting role in a painful grotesquerie of history. The Hotel Majestic was the setting for the Paris Peace Talks, which ground on from 1968 to 1973 and were ill-fated from the start. It is well known now, indeed was known then, that neither the American, the South Vietnamese, nor the North Vietnamese delegation was negotiating in good faith. In the news photographs, one can clearly see the glass behemoths hovering over the negotiating table. Through luck and pluck Vo managed to acquire the chandeliers and now, roughly forty-five years after the signing of the sham treaty, the tableau of lights and cut glass on the floor, seen behind a translucent white scrim, can make you weep if you dwell on it.

Vo is a tenacious and resourceful investigator. He follows a line of inquiry to the point where it can be encapsulated in a specific object—the pen nib, the seat cushion, the room key—that becomes a synecdoche, a stand-in for a whole swath of history, either global or personal, or both.

One of the most haunting pieces in the exhibition, Lot 20. Two Kennedy Administration Cabinet Room Chairs (2013), involved Vo buying at auction two Chippendale-style chairs that were used in the White House Cabinet Room by Defense Secretary Robert McNamara and President John F. Kennedy—the very chairs in which they sat when they made the decision to commit to military involvement in Vietnam. I don’t know if McNamara continued to use the chairs in the years when he wrestled with increasingly grave doubts about the war’s viability or purpose yet continued to advise President Johnson to escalate the destruction, but the history is there. Vo has stripped these classics of American design down to their core structure, yielding several separate sculptures in the process.

In my favorite, the horsehair stuffing from the two seat cushions and backs—thick brown pads of tightly packed fiber, like collapsed beds of shredded wheat or giant, rusting scouring pads—are stacked on a low plinth, their pleasingly rectilinear forms softened and smushed together. Random bits of horsehair fall here and there, like charred pixie dust. It takes but a second for the devastating joke to sink in: a literal deconstruction of the seat of power. As with much of Vo’s work, the sculpture is like a religious relic, and also formally elegant in an Arte Povera way, succinct and tart and faintly ridiculous. It’s a work that says: All of your hubris and your grand designs—all of your power: this is what it has come to. Bricks of matted hair.

Much of Vo’s work operates on a similar principle: an everyday object is the endpoint of a long journey of diminution, of winding down, the bang of history and the resultant whimper. Aside from the obvious symbolism of the seat cushions, the work also seems to be about the childlike desire to break things apart. Who hasn’t wanted to rip all the stuffing out of a cushion, or bust up a piece of furniture, just for the destructive glee of it? Vo has kept alive in himself the reckless impulse that most of us pass through, and the resultant remnants or accumulations of material are in sync with the overall loosening of sculptural conventions that has been going on since the late 1950s. A sculptural form is simply a material that has been acted upon, sometimes just by gravity.

In Vo’s elegant, restrained presentations, the spirit of synecdoche is everywhere. The talismanic object (the hotel room key, the crucifix from his grandmother’s grave, the ordinary cardboard box, now adorned with gold leaf) is in almost inverse proportion to the magnitude of the historical or emotional upheaval it represents. In Vo’s work, it’s as if the pea not only stands for the parable of the touchy princess, but also for the whole system that established the monarchy in the first place and that now keeps those dubious royals propped up. It’s asking a lot of a pea.

Advertisement

In the nineteenth century, an aspiring sculptor would be required to come up with a show-stopper, usually an equestrian statue of enormous size, proving to potential patrons that he could handle big themes and heroic scale. Artists are still at it, especially in the international curated group shows that take themselves as seriously as any summit conference. The piece that put Vo on the map is a full-size replica of the Statue of Liberty, titled We the People (2011–2016). Made from hammered copper mounted on wood and metal supports, it is broken up into roughly three hundred fragments—a giant thumb, a nose, a segment of drapery. Most of the chunks are exhibited in the round, so you can see the scaffolding to which the copper is attached.

The pieces are meant to be distributed to museums and other public spaces throughout the world, and several are included in the Guggenheim show. Two large fragments comprise Lady Liberty’s left hand, split in two, inside and outside, the two halves spaced some distance from each other. The inside of the hand, the palm side, rests horizontally, like an odalisque, on a palette of wood, the four fingers cupped inward, minus the thumb, which is to be found in an adjacent bay. This sculpture, which I think is the best thing in the show, gives the complex experience of seeing the form nearly intact, and also with a view toward the wood and metal scaffolding inside. It’s like turning the stage scenery part way around, exposing the back, which makes the painted illusion all the more poignant. The enormous copper hand, beautifully detailed with rivets and seams, is secured in its cradle of four-by-fours—like something from antiquity. You can imagine it on a barge, floating down the Nile. Wood braces bisect the hand here and there, from forefinger to wrist, and give it somber, Brobdingnagian overtones. Placed near the top of the Guggenheim’s spiral, it’s a striking image: stage décor awaiting its Greek tragedy.

It’s heretical to say it, but Vo could have stopped with one hand. We the People is the anti-synecdoche—it expresses a reluctance to let the part stand for the whole. The startling effect is meant to be amplified by the knowledge that what we are seeing links up with what people are seeing in hundreds of other locations across the globe: we the people. Connectedness is a priori good, as they say at Facebook. But there’s only so much baggage a visual metaphor can carry. It’s merely weighed down, and its own excess purposefulness starts to feel like a burden. In conceptual art, it’s the completing of the task, in this case the distribution of all the constituent parts, that validates the gesture as art; completion as spectacle.

There is not much formal invention in Vo’s work, and I can imagine that he doesn’t particularly value it. Why bother when the world already gives you so much? In this regard, he joins a legion of artists, panning for gold in the sluice of history, who largely eschew invention in favor of presentation. In Vo’s work there is replication and appropriation, finely tuned display, and semi-perverse deconstruction. There is also a “leaving things as they are” quality to his use of materials, by which I mean people, ideas, personal histories, etc. Of course sophisticated people know that presentation is also making, that leaving things as you found them is also shaping a work. But in our hearts, is there really no difference?

Vo’s radicality, the way his work feels transgressive and exciting, has been to take appropriation one step further, to finally acknowledge the utter lawlessness of the artist’s lack of boundaries, to assume that whatever exists in the world is somehow his. In an admiring New Yorker profile by Calvin Tomkins, Vo is quoted as saying, regarding a trove of photographs taken by a man, Joseph Carrier, who befriended him early on and gave him access to his photo archive, “I never thought the material belonged to Joe. I thought it belonged equally to me, so I had no guilt.” That mindset—the fluidity and porousness, the belief that everything belongs to whoever makes imaginative claim on it—is at the center of Vo’s appeal. It calls to mind a remark attributed to Picasso: “A good artist borrows, a great artist steals.”

Once you get acclimated to the level of appropriation—once the brazenness settles down—you can start to look at what Vo has made from a stylistic point of view. Not stylistic in the sense of whether the things are well arranged, but in terms of a work’s vibration, what it aligns with in the work of other artists who have made things that look different from what Vo has made.

For example, a piece from 2009 involves a tattered and stained American flag with thirteen stars, on top of which are applied various military accessories: a bugle, hat, satchel, bayonet, etc. They belonged to a kit made in the late nineteenth century, as part of the US centennial celebration. Vo bought the artifacts at auction and arranged them as they had been shown in the catalog. This piece is taken to mean all the usual things about history and America’s march toward hegemony, but its communicative energy, its affect, is closer to Iced Coffee, a 1966 painting by Fairfield Porter that depicts the poet James Schuyler and a young woman sitting on the porch of Porter’s house in Maine. Both are at a similar remove from their subject, but the Porter looks fresher. Vo’s sculpture, which has the title She was more like a beauty queen from a movie scene, is heavy on presentation. There’s nothing encoded in what he has made that hasn’t already been agreed on.

Some of Vo’s most successful works are a group of freestanding sculptures that join fragments of a French Gothic oak sculpture of the Madonna and Child with pieces of Roman marble torsos and drapery. Chunks of relatively equal visual weight are joined together at a precisely sawn edge, the wooden portion sometimes gently cantilevered over the marble and held in place by a thin brass plate. These are Vo’s most traditional-looking, sculpture-like objects, and their elements, both visual and historical, are in perfect equipoise. They’re not just illustrations of an idea. I like how brazen they are: You’re cutting up the antique sculpture? They’re elegant and also funny and provocative and a tiny bit sad. You can tell that Vo really loves and responds to the original source material and is having a good time fitting the elements together. Who doesn’t love a carved wooden figure whose surface is so worn down that the grain splits apart? And fragments of Roman torsos—do we even have to ask? The profane titles (Your mother sucks cocks in Hell, 2015, for example) come from lines of dialogue in the camp classic The Exorcist, and form the third point in a triad of juxtaposition.

Some of Vo’s art has a tinge of the funereal. A related group of works from 2008–2009 came about when Vo bought a medieval wood carving of Saint Joseph in Amsterdam and realized he had no easy way of getting it back to Berlin, where he lived at the time. Vo did the expedient thing: he sawed the sculpture into pieces exactly fitting into various airline carry-on bags. I can imagine that making that first cut must have been an exhilarating moment, and once accomplished, there was no turning back. Now anything that could be bought could be cut up, for art’s sake. It’s impossible to peer into the bags and see the cleanly sawn chunks of wood and not think of the work of the hit man—the dismembered body in a suitcase—which is not a bad metaphor for an artist.

The fifty-year project known as Conceptual Art, the umbrella term for all the varieties of art-making, from the hermetic to the populist, that are independent of painting and sculpture, has now, in its third, fourth, and even fifth generations, congealed into a more or less predictable formal language. It includes works that use objects or images, and works that primarily depend on actions, with some artists, perhaps most, working with some amalgam of the two. What binds these diverse forms of expression together, and accounts for the genre’s surprisingly durable popularity with museumgoers, is their embrace of the story.

Narrative is used to generate a work’s structure and also to provide the key for its decoding. It’s the kind of contract between viewer and artist that was sought after, futilely so, during the reign of abstract painting. Why won’t the artist tell us what it means? Now one has only to read. We learn the story behind Vo’s objects, and its relationship to his themes and concerns, from the copious wall texts, which are to the art as “leading the witness” would be in a court of law. The texts almost become another object alongside the art. The object has an object; it’s as if the moon had its own moon.

Most of the conversation around Vo centers on his biography, his personal intersection with history and with his far-reaching themes. But Vo’s affect as an artist—a measure of the emotional, intellectual, and stylistic frequencies that his work gives off—cycles through a few different stops on the map: an almost Dada-like disregard for pieties surrounding objects from the past (everything is material); decorative minimalism; the gumption to overturn rocks unseen by others; and a faint whiff of “See if I care.” To paraphrase Sybille Bedford, Vo acts as though he expects the world to have the faith in him that he has in himself.

If you’re in a receptive frame of mind, Vo’s constructions, undergirded by their expansive connect-the-dots wall texts, can induce a little gasp, that “Ohhh” of recognition. The dismantled chandelier is a stand-in for the collapse of overweening, hubristic ambition and the destruction it wrought. The story’s all there, it’s not pretty, and we’re mostly all complicit, one way or another.

But halfway down the Guggenheim’s ramp, the effect starts to pall. The work starts to lose steam because of a sameness. Vo has only so many arrows in his quiver, only so many stylistic moves at his disposal. The themes recycle (true for most artists), and so do the visual tropes (also true for most artists). Another mash-up of two kinds of statuary, another appliance or manufactured object, and yet another set of rusted tools dangling from the ceiling. All very stylish and conceptually interesting, but without a lot of inside energy.

A retrospective is a brutal test. With relatively little formal invention to vary his presentations, Vo’s relationships to his subjects are all at the same latitude.* In this kind of art, how the artist structures our attention is vital. So much of comprehending it is completed offsite, as it were—all that external connection-making, egged on by the wall lables—that if not done right it tends to snap your attention away from the work, not toward it. It’s like an orchestra conductor bringing the woodwinds in too early.

Vo’s sleek art may be a new hybrid form, part literary and part visual. The impulses to memorialize, criticize, and eroticize are all mixed together, and sometimes the result has the focused, compressed clarity of an epiphany, as in the deconstructed chairs; other times there is a feeling of something being stretched too thin. Vo seems to want to be the visual equivalent of a writer like W.G. Sebald, in whose work the accumulation of neutrally observed details, some personal, others historical, creates a devastating critique of the victor’s narrative, one that reverberates across nationalities. But to be that kind of artist Vo might have to be more than an arranger, as well as show less preciousness.

Vo makes forms speak, but just as in the world of the theater, it takes a large institutional apparatus, with many behind-the-scenes workers, to make the voice audible. This is not a criticism, but I think we should at least acknowledge that the idea of the autonomous art object, which perhaps never existed except as an ideal, has now been left behind. Today’s art is a group project. In a way, Vo is the epitome of the new kind of artist for whom institutions, along with the people who run them, are but one more material—perhaps the real clay—to be shaped.

It’s easy to see why Vo’s work has been taken up by a certain segment of the curator class. It rests squarely in the middle of the zeitgeist and the art vocabulary of the moment. It is also elegant and spare and easy on the eyes. It remains to be seen of course how it will look in the future, to eyes not already primed to read the overdetermined wall texts, or to minds not preoccupied with issues of today. In time, the last words from Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost might apply to Vo’s art and its reception: “You that way; we this way.” Or not.

-

*

I borrow the phrase from Laura Kipnis, writing recently in these pages about the novelist Lynne Tillman. ↩