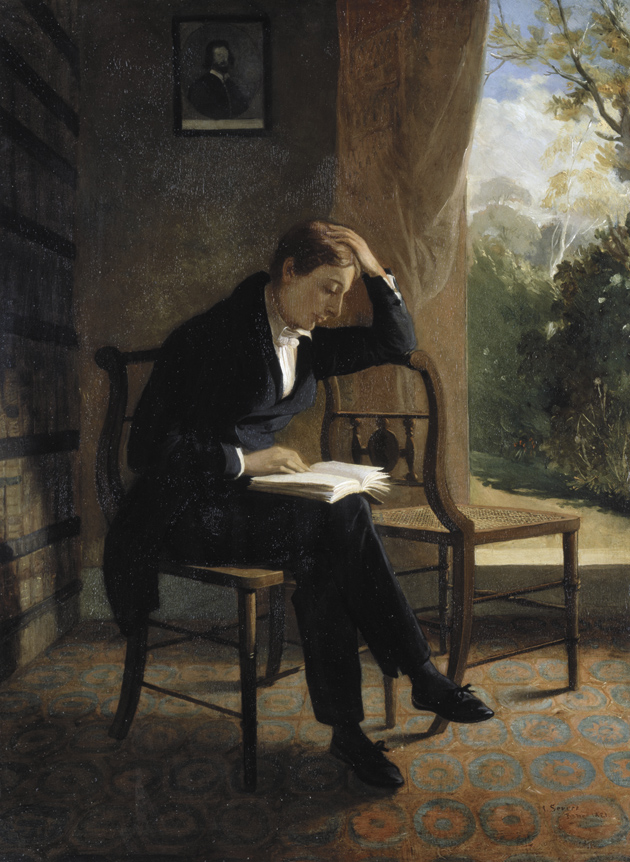

National Portrait Gallery, London/SuperStock

The poet John Keats, in a painting by his friend Joseph Severn, who nursed him in Rome until his death from tuberculosis in February 1821. Severn said of this portrait, ‘This was the time he first fell ill & had written the Ode to the Nightingale on the morning of my visit to Hampstead. I found him sitting with the two chairs as I have painted him & was struck with the first real symptoms of sadness in Keats so finely expressed in that poem.’

Rome, November 30, 1820. John Keats, who at the age of twenty-five has less than three months to live, is writing to his friend Charles Brown in England:

I have an habitual feeling of my real life having past, and that I am leading a posthumous existence. God knows how it would have been—but it appears to me—however, I will not speak of that subject.

The word that rotates, “but,” is rounded upon, in its turn, by the word “however.” Keats, with a courage that is something better than unflinching (for the unflinching may be not so much courageous as foolhardy), declines to speculate on what might have been his prospects in love and in art, and on what those prospects now are, here and hereafter. He makes deeply real, within real life, a line of thought that has become the shallowest of modern injunctions: Let’s not go there. His unwavering decision, painful and pained, is to treat his friend with the utmost, the uttermost, decorum.

He was leading a posthumous existence as he lay dying of consumption. It was proving to be “a long day’s dying to augment our pain” (Adam’s vision in Paradise Lost of what lay in store for mankind after the Fall). Our pain as well as his. A posthumous existence was a paradoxical thought at the time that Keats voiced it; it would soon (not, given his agony, all too soon) become no longer a paradox but a plain truth, when he entered upon the only kind of afterlife that he could continue to believe in. His belief contained an acknowledgment of the dark doubts about art’s worth that many great artists have found themselves suffering.

Moreover, for Keats, his had long been a hope at once firm and tentative: “I think I shall be among the English Poets after my death.” For it is I think that gives the asseveration such grace and dignity, so that a small but not insignificant wrong is done when (on a couple of occasions in Posthumous Keats) his precisely guarded hope is indurated into “his statement to his brother George, in 1818, that he would be among the English poets after his death,” within “a future that meant to place him ‘among the English poets.'”

Stanley Plumly’s profoundly humane evocation of Keats’s life and his immediate afterlife is better than magisterial, for it is masterly. Characteristic of the attentive powers is his pausing upon Keats’s word past: “my real life having past.” The last word does double duty and more than duty, this having passed into the past. The book is supremely well informed, by means not only of sheer information but of the larger—the Keatsian—sense of what it is to inform. Here is imaginative realization, with width as well as depth of sympathies. Even while Plumly knows that there is no substitute for knowledge, he knows that this is because there is no substitute for anything: for, say, conviction, sensibility, intelligence, honesty, curiosity such as does not kill but gives life, and love. While this “personal biography” never relinquishes its confidence that there are crucial assurances that can be both given and taken, it succeeds in holding such assurances in respectful balance with Keats’s complementary concept and precept, ” Negative Capability, that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason.”

Plumly’s is a generous book, avowedly grateful to what he calls “the great 1960s biographies” of Keats, that by Walter Jackson Bate, which I’d characterize as the most cognitive; by Aileen Ward, the most touching; and by Robert Gittings, the most practical. Plumly pays justified tribute to the fine editors, too, notably Hyder Edward Rollins, for Keats’s letters as well as all the papers of the Keats circle, and John Barnard, for the poems. These debts are honored; for his architectonics, Plumly is in debt to no one. Thanks to acts of arbitration that are not simply arbitrary, he is able to exercise to the full his own shaping spirit of imagination, and to have each chapter be “formed from a single image, theme, or object relative to Keats’s vulnerabilities as an individual and his strengths as an artist.” The happy result, sensitive to the darkest unhappinesses, is a work that is markedly personal, while never becoming self-conscious, idiosyncratic, or eccentric.

Advertisement

At the center of Posthumous Keats is the journey deathward. A threefold image is constituted of how Keats was pictured, of how he was treated medically (the art that was practiced both upon him and by him when younger), and of how he loved and was loved. In illuminating all of these for us, Plumly is acute in what he notices and in how he notes it down. He writes with lucid tact and with apt implication. Here is Keats in the summer of 1820, at his rooms in Kentish Town:

He lay there on the floor of the second story in the heat, with the rust taste of blood in his mouth, for most of the rest of the day, late afternoon and the closeness of the humidity and the weight of the ceiling pressing down on him.

There is nothing ostentatious about this, but Plumly’s being a poet animates his prose. Not rusty but rust, as more brutal of sense and as more tellingly continuous of sound: rust taste… most… rest (the turning of rust to rest), with closeness as both atmosphere and proximity, and then with ceiling pressing as giving the noun ceiling the weight of a further participle.

This is a style that is alive to undercurrents, as when “Here lies one whose name was writ in water” moves a little later into “Keats’s undercurrent of guilt about leaving his brother.” There is deft evocation, whether of a portrait (“Keats’s firm fist anchored at the cheek”), of a benign transition (Keats, having spoken of “a cold hill,” soon “warms to the sight”), of a shudder at the weather (“the chilblain climate of coastal Scotland”), of cautiously precarious physical movement (“the loose gravel” that is “making traction to the unwary tricky”), of a horrible fluency (“coughing blood consistently—that is, phlegm flecked with blood”), or even of a simple preposition— into —and how it can bring home a haunting pun (“he has pored his eyes into books”). Of the Eternal City, where Keats entered into eternity, Plumly writes with lapidary power: “The eternal is history, piled, or plied, against time. It is not ethereal, but stone, whatever form it has fallen to.”

This excellent prose is yet more evidence, if more were needed, that Plumly has read Keats to very good effect, has been appreciative of Keats’s effects. Here is wording to trust, not least in the way in which it is willing to risk being misunderstood in the service of such courage as Keats himself could evince in confronting what he had to endure. Charles Brown averted his eyes and his mind from the medical horror (with what Plumly sympathetically calls “an understatement of hope in the face of fact”) when he reported Keats as having “a slight inflammation in the throat.” Plumly is right to catch this, in a figure of speech that could have been corporeally maladroit, as “both stiff upper lip and dangerous denial.” The biographer’s suggestive vigilance attends to the same quality in Keats, as when Plumly draws out the double sense of the word before (place and time) in Keats’s scorn of poetasters in “The Fall of Hyperion”:

Though I breathe death with them it will be life

To see them sprawl before me into graves.

The biographer is at one with his subject in all such fine fidelity of phrasing. So it was that Keats made serious play with give up, when he moved from announcing that he had “given up Hyperion“—the first version, which he abandoned—to “I wish to give myself up to other sensations.” The poet in Keats informs his being a prose writer of genius, as when he delights in the word vale (which appears in the opening line of Hyperion):

There is a cool pleasure in the very sound of vale. The English word is of the happiest chance. Milton has put vales in heaven and hell with the very utter affection and yearning of a great Poet.

This is not half-formed poetry, it is fully formed prose, finding a cool pleasure not only in the one word and in Milton’s surprising us (“Milton has put vales in heaven and hell “) but in the rhythm of Milton, the English heroic line that is audible in Keats’s cadence, “The English word is of the happiest chance.” Plumly has an eye and an ear for words and their curiosity. After quoting a description of Keats as an invalid, he adds: “Curious word that ‘invalid,’ because it refers not only to the disabled but to the non-valid as well,” given a poet “whose name deserves to be disappeared.”

Advertisement

The manner of the whole book is one that can accommodate the tentativeness that is so Keatsian: “To night I am all in a mist; I scarcely know what’s what.” Plumly remarks of the great odes, with tenderness, that they are “poems that scarcely know what is what, and that thrive in that ‘scarcely.'” Braced against such delicacy is a Keatsian counter-quality, robustness. As when Plumly immediately follows Hyder Edward Rollins’s description of Keats’s friend Charles Brown with a straightfaced laconicism: “‘Brown was a strange mixture of coarseness, kindliness, cold-bloodedness, and calculation.’ He was a Scot, and…”

The tragic medical story has always been told with great feeling. To this honorable tradition Posthumous Keats contributes a saddened acumen. That Keats’s Hampstead was known as “the lungs of London.” That when Keats writes of the ill health of his friend James Rice, he is thinking of his brother Tom—not ignoring Rice and thinking only of Tom but thinking of Tom too. That though bloodletting is now known to be a misguided treatment, Keats himself had been a practitioner of it. That it was not until the 1840s that “consumption and the symptoms of tuberculosis became synonymous, though the tubercle bacillus itself was not identified until 1882.” And that Keats’s friends and his doctors, all of them, clung to the belief that it was not his lungs but his stomach or his mind that was at the root of his illness, and that this belief was clung to even by Keats himself, against his better knowledge of how much worse his condition was, how fatal. (It is an admirably level epithet for the medical men that Plumly comes up with: “however much he wanted to believe his deficient doctors.”)

It was as late as March 1820 that Brown believed that he could offer an assurance, even offer it twice within the one letter: “Keats is so well as to be out of danger”; “I consider him perfectly out of danger, & no pulmonary affection, no organic defect whatsoever,—the disease is on his mind….” The pincer jaws converge, the two possibilities that are equally but differently excruciating: the tragic if only, and the no less tragic conviction that there had never been any hope.

Plumly points out the unexpected turn, verging on a malapropism, in Brown’s preposition: the disease is on his mind, not in it. One might add that when Joseph Severn, the friend who nursed Keats during his dying days in Rome, said that “his mind was most certainly killing him,” there is again something of a flicker: most certainly his mind, or most certainly killing?

One of the strengths of this book is its not yielding to indignation, and particularly not to a very insidious form of it, on behalf of another. Keats, though, had a perfect right to indignation, directed not at how death in life was treating him, for there is no sense in indignation at such anguish, but at how he was finding himself treated by the enemies (the hostile reviewers) and by the condescenders (for instance, his publishers). The Publisher’s Advertisement within his 1820 volume concluded by saying of “the unfinished poem Hyperion “: “The poem was intended to have been of equal length with Endymion, but the reception given to that work discouraged the author from proceeding.” In Plumly’s account, we witness Keats’s retort:

In one of the book’s gift copies he strikes out the entire paragraph with cross-hatching and writes at the top of the page that “This is none of my doing—I was ill at the time,” then, for emphasis, right under the Endymion part of the sentence, adds, “This is a lie.”

The lie, which soon became an untruth (for people came genuinely to believe this ungenuine account), was that Keats’s sensibility, his sensitivity, the thinness of his skin, and the coagulatory thickening within his troubled mind were responsible first for his abdication, so discouraged was he by the reception of his poems, and then for his death. The seal was notoriously set on this by Byron’s glazed wit:

John Keats, who was killed off by one critique,

Just as he really promised something great,

If not intelligible,—without Greek

Contrived to talk about the Gods of late,

Much as they might have been supposed to speak.

Poor fellow! His was an untoward fate:—

‘Tis strange the mind, that very fiery particle,

Should let itself be snuffed out by an Article.1

The trouble, or rather one aspect of the turbid trouble, was that Keats’s friends and admirers came to concur with the misrepresentations. The nameless marble tombstone that was set up in 1823 had been contested among his friends but it stood sturdy in its insistences:

This Grave

contains all that was Mortal

of a

YOUNG ENGLISH POET

Who

on his Death Bed

in the Bitterness of his Heart

at the Malicious Power of his Enemies

Desired

these Words to be engraven on his Tomb Stone

“Here lies One

Whose Name was writ in Water”

Feb 24th 1821.

Plumly rightly makes a concession but not to Shelley, who was of no help and perhaps did not really mean to be: “The rumor [that he had been killed by venomous reviews] was in the air, easy to believe, and too few of his friends disbelieved it. But it is one thing to speak an opinion or note it in a diary; it is another to publish it, which Shelley did, to incalculable effect—once Keats was dead—in his Preface to Adonais.”

The circumstances of the closing scene of poor Keats’s life were not made known to me until the Elegy was ready for the press. I am given to understand that the wound which his sensitive spirit had received from the criticism of Endymion was exasperated by the bitter sense of unrequited benefits; the poor fellow seems to have been hooted from the stage of life, no less by those on whom he had wasted the promise of his genius, than those on whom he had lavished his fortune and his care.

One central impulse of Posthumous Keats is its scrupulously pertinacious determination to set the record straight. This means the demonstration, in detail that is often subtle and sometimes stark, of the misrepresentations of Keats in the wake of his death. There are the visual representations, his portraiture, his gravestone, all the ancillary figurings of him, and there are those in words, some of them as poems or as biographical reminiscences, some of them taken up within the funerary images, as epitaph, as brief life, or as rebuke.

Brown’s pencil drawing (1819) “stands alone against the beautification of Keats that would compromise later renderings by professional artists.” But it is Joseph Severn’s deathly portrait (January 1821) that here moves Plumly to a superb evocation, extended even as Severn’s powers as an artist had been extended by his tending of the suffering Keats:

The event of his death has been so long in coming, as if it had been postponed as a test, that here at the last, in what seems the final, incremental hour, it feels wholly internal, invisible, mysterious, like a state between life and death. The intimacy, the silence, the imperceptibility of the corporeal crossover, the secrecy with which the breath, the spirit, escapes the body—all of this unspoken and unspeakable quality enters into Severn’s deathbed portrait. And it is as graphic as it is lyric—the night sweats, the dampness of the bedding, the way Keats’s dark hair drapes his forehead.

Although he does not say so, Severn must have made the drawing in part because he did not know what else to do that night and in part because art was his first—for better or worse—language. He claims he drew the picture in order “to keep me awake.” The source of light in the cell-like bedroom is of course a candle off to the left, leaving the artist in shadow, like a witness. The peace on Keats’s face is both fatal exhaustion and acceptance. And though death, on February 23, is still three weeks away, he looks, after his terrible literal and figurative journey, to have arrived, even disappeared into arrival. The artist in Severn creates a large black sun to relieve the face against in order to emphasize the angle of the resting, lifted three-quarters profile. This circular backdrop is massive in its animation, dramatic in its contrast. Sleeping or dead, Keats seems to be dreaming.

This, at once sublime and touching, is a triumph worthy of Severn’s masterpiece. Plumly respects the coincidings that both shadow and enlighten a man’s days, and his word graphic makes it all cohere: “ministering to the daily graphic needs of a sick and dying man, Severn grew in the same role that Keats himself had filled in his service to his brother Tom just three years earlier.” Plumly even risks—successfully—a locution that could have been shockingly insensitive: “Severn, as luck would have it, will die in Rome at eighty-six, his iron constitution unalloyed to the last.”

The portraiture of Keats, though, was not unalloyed: “Any resemblance once captured by Haydon or Brown or even Severn becomes not only diluted through imitation and time but distorted by assumption.” Of course Plumly is aware that he too, like all of us, is at once assisted and impeded by assumptions. He rightly sees the respects in which all of Keats’s friends on occasion propose something that is self-serving, an epithet that comes several times but not censoriously and not self-exculpatorily (for Plumly’s enterprise, too, has a self to serve). But he takes not only the right line but the right tone, as when he regrets the “imposed Victorianized idea of what a poet should look like” and the circumstances in which “the reality of the poet becomes compromised by a good many things.” Oscar Wilde judges the medallion portrait of Keats to be “a very terrible lie and misrepresentation,” but largely on the grounds that it does not show Keats as lovely enough. W.B. Yeats patronizes Keats in a dozen lines of verse that manage to invoke “almost every cliché associated with John Keats of a century before.”

Differently sad is the understandable but dismaying contention among Keats’s friends about how best to remember him and to memorialize him, whatever the medium. This was “a falling out of friends that would obscure and delay a true picture or an accurate portrait of a poet unknown outside their small imperfect circle.” Severn wrote to Brown about “how singular” it was that they could not agree upon Keats’s epitaph. Good word, singular, given the plurality of dissenting opinions. Fortunately there are truly comic aspects to the whole tragic business, and Plumly is at his best when he finds himself able duly to relax (without ever relaxing his intelligence) as he comes to investigate Keats’s brief encounter with Coleridge: “There are three versions of this one-and-only meeting between the obscure young poet and the established, renowned figure.” We should put our money not on either of Coleridge’s confections, but on Keats’s catching of Coleridge’s cascades of speech:

I walked with him at his alderman-after dinner pace for near two miles I suppose In those two Miles he broached a thousand things—let me see if I can give you a list—Nightingales, Poetry—on Poetical sensation—Metaphysics—Different genera and species of Dreams—Nightmare—a dream accompanied by a sense of touch—single and double touch—A dream related—First and second consciousness—the difference explained between will and Volition….

“Almost every friend or acquaintance within the Keats circle would sooner or later propose a Keatsian monograph, memoir, or biography”—and Plumly lists eight of them. “Once Keats, as a unifying figure, is gone, his friends will find any number of things to disagree about.” One of them is money, about which Plumly is characteristically sane: “Money, when it relates to families, is not only a complexity but an opacity, and no one and everyone is usually to blame.” It is the word blame (as again in the observation that Brown blames everyone except himself) that made me realize why a great formulation by T.S. Eliot had been coming to mind in praise of Posthumous Keats. Of the novelist Charles-Louis Phillippe, Eliot said, “He is both compassionate and dispassionate,” going on immediately, “in his book we blame no one, we blame not even a ‘social system.'”

It is a mark of this biography’s distinction that there is so much that I for one (and not alone) would wish to address in gratitude. There would be the relation of its findings to the wider context of Samantha Matthews’s remarkable book, Poetical Remains: Poets’ Graves, Bodies, and Books in the Nineteenth Century,2 with its passionately precise chapter on Keats and Shelley. There is the further range that might follow from adducing Michael Millgate on the afterlife of Tennyson, Hardy, and Henry James, in his fascinating study Testamentary Act.3 There would be all the considerations that bring Samuel Beckett to mind when attending to Keats: “deathwards progressing/To no death was that visage.” And when Keats asks his doctor “How long is this posthumous life of mine to last” (Severn gives no question mark), I am moved to weigh the words of Bishop Butler in The Analogy of Religion:

So that our posthumous life, whatever there may be in it additional to our present, yet may not be entirely beginning anew; but going on. Death may, in some sort, and in some respects, answer to our birth.

But the person with whom to end may be she of whom Keats, suffering more than one kind of pain, could not but think to the very end. Plumly is singularly fair-minded and full-hearted in his apprehending of Fanny Brawne, with whom Keats had fallen in love in 1818. She was to keep the memory of Keats not green but dark, keeping him a secret from her husband. So my praise of this personal biography of Keats ends upon the note of a poem, published this year, that imagines a personal autobiography of Fanny Brawne—or rather Fanny Lindon. The poem of fifty-four lines by Debora Greger4 is a store of felt life and afterlife, addressing the reticences, memories, and family circumstances of Mrs. Lindon. Here is how and where it opens:

HER POSTHUMOUS LIFE

How long is this posthumous life of mine to last?

—Keats to his doctor, Rome, 1820

I remember where I am,

for the light of London enters the room,

grimy as a chimney sweep.He is here, too, in the corner

he has taken for his own, just a shade

in the shadow of the curtains.He whispers his name,

which was to have been mine as well,

and I find myself possessedof that lost girlishness

he claimed would slay him. But did Death call

at Wentworth Place?No, Death booked passage

from Gravesend to Naples, then shared a carriage

on the Roman road.

“Her Posthumous Life,” alive to the vanishing of Fanny Brawne, draws to its respectful close:

Who knows how long

I have nursed this ghost? In a moth-eaten redingote

long out of style,he dictates to me

his latest, an ode. I do not like it, though

I do not appear.To Darkness , it begins, and then goes on. Goes on into darkness,

knowing the weight of earth.

Keats had written to Brown as he set sail for Rome: “The thought of leaving Miss Brawne is beyond every thing horrible—the sense of darkness coming over me—I eternally see her figure eternally vanishing.”