“Restricted: Language.” Meaning that what you are about to watch is not a silent film? No, a movie with a blue streak.

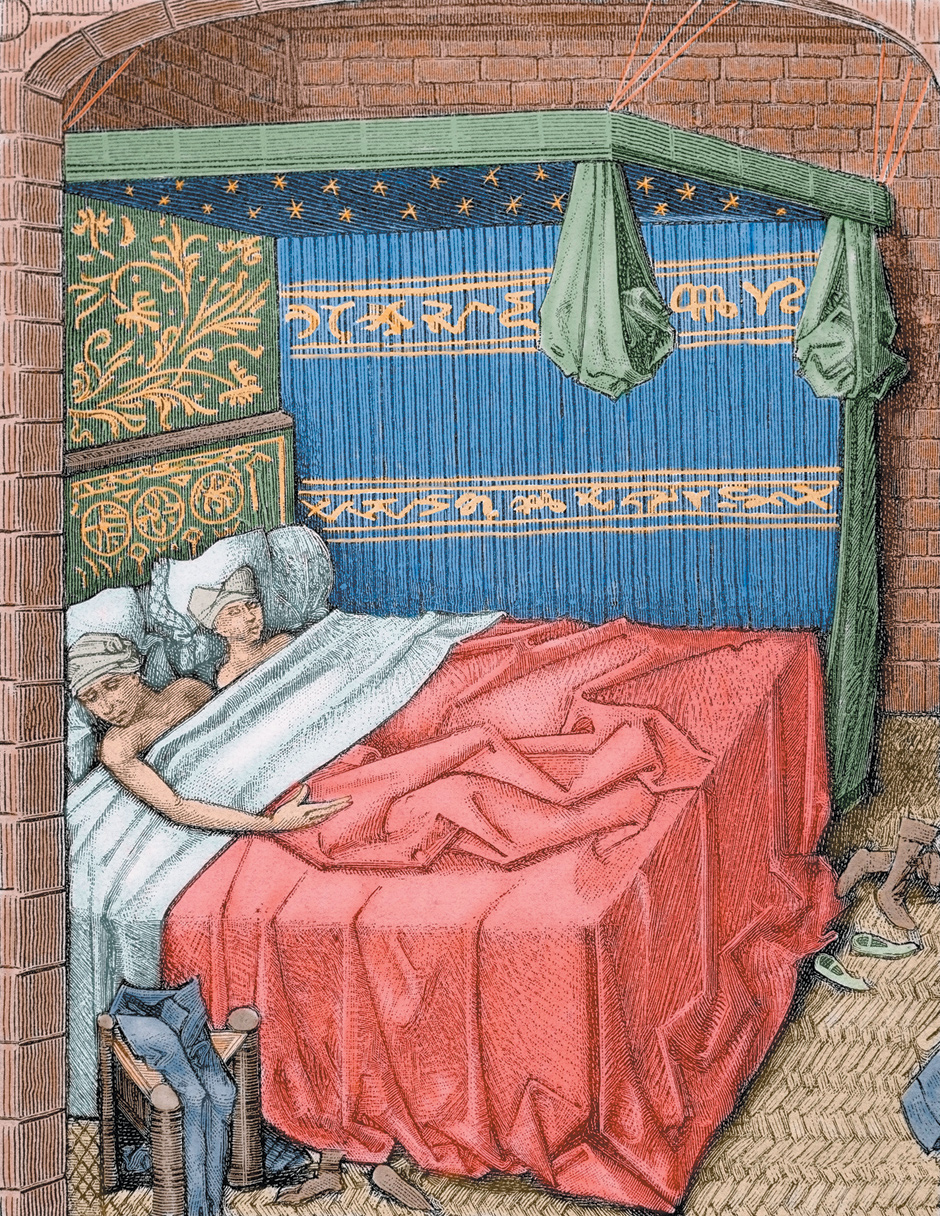

What is a fabliau, exactly? The French dictionary says simply that it is a medieval story in verse, “popular in character, most often satiric.” But “broadly” may be a fitter word than “exactly,” since the broad humor of the Old French fabliau calls a spade a spade. “The Cunt Made with a Spade” (Du con qui fu fait a la besche) can stand as Exhibit Number 1, being the very first of the fabliaux in this thousand-page, twelfth- to fourteenth-century compilation. Understood, as it is again (and again and again) when we encounter—to continue with the c-word—“The Cunt Blessed by a Bishop,” “The Knight Who Made Cunts Talk,” and “Trial by Cunt.” Enter “The Mourner Who Got Fucked at the Grave Site,” flanked by “The Fucker.”

Genitals are not blackballed: “Black Balls.” Scatology does its business: “Long Butthole Berengier”—likewise, “The Piece of Shit,” when the husband tucks in. But then the only person who can have his cake and eat it is the coprophage. Or, in the famous retort of the lavatory-cleaner, “It may be shit to you but it’s my bread and butter.” “The fabliau authors,” Nathaniel Dubin reminds us, invented metaphors and “enlarged on them in tasteless detail.”

True, we ought never to forget what Yeats remembered, that “Love has pitched his mansion in/The place of excrement” (“Crazy Jane Talks with the Bishop”), but then so has Lust, and Lust has a way of quickly becoming repetitious and very, very boring. Within the fabliaux, not finding any of this funny is found particularly funny, especially if it happens to be a woman who is uptight: “The Maiden Who Couldn’t Abide Lewd Language.” But then the fabliaux unremittingly have it in for women. “The Gelded Lady” has apparently asked for it, unlike the Female Eunuch.

The fabliau, then, is a short story that is a tall story. It combines a burly blurting of dirty words with a reveling in humiliations that are good unclean fun. A popular venture that is keen to paste—épater—everybody (not just the bourgeoisie), it is the art of the single entendre. Highly staged low life, it guffaws at the pious, the prudish, and the priggish. High cockalorum versus high decorum.

Yet the obvious snag rises at once: Is it any longer possible, these days, to thrill to indecorum, given the fact that decorum has long since vacated the field? When I was young or younger, there were jokes that didn’t just seem to me to be funny, they were funny. Their worth depended on their coming on as anti-chameleons, figures that delighted in taking on the color opposite to that of the orthodox ground upon which they were now being themselves. Many of these jokes had only a schlock-value, but at least their line (Lenny Bruce–wise, when, hard upon the heels of a truly outrageous remark, he would add, “Hope I’m not out of line”) could be the worthwhile one of counteracting the genteel, the self-righteous, and the sanctimonious. A wife deplores her husband’s having been, on occasion, crude, whereupon he proceeds to catalog his inclinations and his clubman’s courtesies, finally clinching it all with “So what’s all this ‘crude’ shit?”

Scarcely to be lamented, the current unworkability of a very limited joke like that one. But what about this one? Two friends at Heathrow, one of them spotting the Archbishop of Canterbury, or so the man believes. The other says: “Nothing like him.” Counter-insistence. “All right, then, go and ask him.” The exchange, watched across the lobby, the air of puzzlement, then the return to his friend. “Well?” “He was noncommittal.” “What do you mean, he was noncommittal?” “Well, I asked him if he was the Archbishop of Canterbury and he said ‘Fuck off.’”

Never explain a joke, they say, but one can try to identify what prompts such gratitude as one may have. It is noncommittal that does it. No synonym would even begin to do this trick. A fictive anecdote like this is a compacted fabliau, happy at what indecorum can felicitously bring about—but this only within a world that knows or remembers what decorum is. But in our day it is no longer inconceivable that we might actually find ourselves landed with an Archbishop of Canterbury who saw it as his duty to, you know, reach out, demotically, democratically. Inside every Primate there is, after all, a primate. And one remembers William Empson’s praise of the Church of England for having kept Christianity at bay.

Decorum and indecorum are symbiotic, they are the fungoid and algoid that constitute lichen (Beckett’s crucial symbiosis, down there and up there with Dives and Lazarus). The first sentence of R. Howard Bloch’s introduction to The Fabliaux emphasizes that these poems were “opposed to the official culture and high-minded teachings of the Church.” But since our own all-but-official culture is in the habit of bowing its knee to low-mindedness, this must raise the question of how we can now be expected to find low-mouthedness duly outrageous. This, I’m afraid, even on the occasions when bowing the knee to low-mindedness does have something to be said for it. As with the cover of Private Eye and its speech-bubble exchange between a reporter and President Clinton. “Did you ask the witness to lie?” “No Sir. Just kneel.” Or, for the Maiden Who Couldn’t Abide Lewinsky Language and who prefers it when—as Edward Gibbon put it—“all licentious passages are left in the obscurity of a learned language,” mea gulpa.

Advertisement

Although it is not the same as altogether recognizing the problem, The Fabliaux does nod toward the difficulty, here in our un-outrageable world, when it comes to these “outrageously obscene, anticlerical, misogynistic fabliaux, which wildly violate any notion of bourgeois respectability.” Not any notion, for there soon has to be a wistful concession:

Yet there are limits to their daring. When we consider what is missing, for example, even the sexually explicit fabliaux strike us as almost prudish by today’s standards. The man is invariably on top but for one comic exception, oral sex is entirely absent, and the rare instances of same-sex relations are all misunderstandings.

Just as satire comes to nothing in a world in which there is scarcely any place any longer for panegyric (yet the one is the other’s flying buttress), so the fabliau can live happily only within a world in which its counterkind is alive and well: romance. The introduction here, like the translator’s note, tells well the story of the comic tales, anonymous for the most part, usually two or three hundred lines long, of which about 160 exist. (The translator decided that the best end was with number 69.) The illuminating entry on the fabliau by Sarah Kay in The New Oxford Companion to Literature in French

1 convincingly brought into play the romances, for without them there could be no game and nothing gamey:

A major turning-point in fabliaux scholarship came with the realization that many of them are burlesques of courtly texts, and that their obsession with what goes on below the belt results not from lower-class philistinism, but from carefully targeted parody (Nykrog, 1957). Fabliaux and romances might, it became apparent, be enjoyed by the same audiences; they might even be composed for them by the same authors.

Parody, even when carefully targeted, is perfectly compatible with philistinism, but the larger point is that those of us who do not know the medieval romances may be unable to find much pleasure in a fabliau that banters or ridicules them. Even Don Quixote suffers from our ignorance of the romances that were not the blank foe of Cervantes but the condition of his humor. When an English literary historian remarked in 1823 that “some of the Fabliaux very nearly approach the romances of chivalry” (this is The Oxford English Dictionary’s second citation for “fabliau,” the first being 1804), we need to understand this “approach” in two senses. First, that some of the fabliaux were of a romantic, not a cynical, nature; and second, more tellingly, that the coarse ones (which really made the running, and which more than dominate The Fabliaux) always stood in need of the abutting company of the romances, bringing about the counterthrust that gave both parties a reason for existing. The ludic lewdster was always in collusive collision with the straight or straitlaced man.

“The wit and linguistic sophistication of these texts have been increasingly demonstrated,” wrote Sarah Kay, no doubt truly, but most of us are just going to have to take her word for it. The fabliaux may represent “a world in which the ingenious triumph over the unimaginative,” but all too often the tale proper is too predictable to be a triumph of anything over anything. “Almost without exception”—a dispiriting turn of phrase, this—“the fabliaux present us with lecherous priests, self-serving and none-too-courageous knights, coarse and lazy peasants, and deceitful women…. They didn’t idealize their world; they accepted it as it was” (Dubin). But the world is everything that is the case. Only a coarse and lazy poetry is in the habit of pretending otherwise.

The word “pornographic” was enlisted by Kay, “pornographic, in the sense that their narratives revolve quite blatantly around the size and suitability of sexual organs, and the quantity or frequency of sexual performance.” Revolve is good, and yet the characterizing is less so. Obscene, the fabliaux often are; pornographic, never. “The Ring That Controlled Erections” never has to control any in its readers. Rather, the fabliaux inhabit the world that the Honorable John M. Woolsey in 1933 mistakenly judged to be the world of Joyce’s Ulysses. “In Ulysses, in spite of its unusual frankness, I do not detect anywhere the leer of the sensualist. I hold, therefore, that it is not pornographic.” Rather the reverse: “whilst in many places the effect of Ulysses on the reader undoubtedly is somewhat emetic, nowhere does it tend to be an aphrodisiac. Ulysses may, therefore, be admitted into the United States.” (But what about us aphrodisiacs? cry the oysters and the Spanish flies. Why can’t we be admitted into the United States?)

Advertisement

In the early twentieth century, wrote Kay, “fabliaux were regarded as a marginal genre, and were certainly not considered suitable for students; an early student anthology (edited by Johnston and Owen, 1957) complains that ‘half of the total violate modern susceptibilities to a serious extent,’ and confines itself to exemplars that are ‘reasonably acceptable.’” But modern susceptibilities—a delicate way of putting it—have now changed in ways that are doubly unfortunate for the fabliau. On the one hand, outrage at bad language or at scatology—Norman O. Brown’s excremental vision, or “Here’s mud in your eye”—has long found itself evacuated. As for outrage at anti-clericalism (“I’ll tell the Vicar”—“I am the Vicar”), forget it, for it would now be pro-clericalism that would outrage your average student of literature.

On the other hand, outrage does still have its field day—but at the very place where the fabliau pitches its mansion. A bland editorial hand is therefore called for and called upon. So misogyny may find itself mollified into “a certain antifeminism,” and even when the contemptuous hatred of women is called by its true name, there will somehow be an air, not of excuse me, but of excuse them. “Misogyny, rape, severe beatings, mockery of the disabled, et cetera, did not disturb them as it does us.”

My sweet old etcetera. The historian, as so often, is not sure quite how to put it, and wonders whether to plead extenuating circumstances or to chivvy us along. Did not disturb them as it does us. (Father Kenelm Foster on eternal torment: “As a medieval Christian Dante was not in the least disposed, as modern readers may be, to find the very idea of damnation unacceptable. His robust faith could take the idea for granted.” Robustly put.)

Get your wife used to thrashings, say

two or three or four times a day

on the first of the week, or ten

or twelves times every fortnight; then

whether she’s fasting or is not,

she’ll grow in value quite a lot.

Rhythmically, this seems to me a nonstarter, though Howard Bloch praises Dubin’s translation very highly indeed:

These letter-perfect renderings of the original, honed to the highest philological standard, chime marvelously with the light tone and lively pace of the rhymed Old French octosyllabic couplet.

I must acknowledge that I have no Old French, so I can’t tell whether the translation above fails to do justice to such merits as the original has, there on the facing page:

Qui acoustume fame a batre

.ii. foiz le jor ou .iii. ou .iiii.

au premier jor de la semaine,

.x. foiz ou .xii. la quinsaine,

ou ele jeünast ou non,

ele n’en vaudroit se mieus non.

“Not until the present translation has a significant body of the fabliaux been available in a modern anthology—in French, English, or any language—for the general reader.” But will the general reader really want to stump up for the five hundred of these thousand pages that are in Old French? True, The Word Exchange: Anglo-Saxon Poems in Translation has recently proved both a critical and a business success, but The Word Exchange consisted of poems of very many different kinds, and it marshaled a very fine team of translators.2 The Fabliaux, honorably presenting all the Old French, will either encompass two readerships or it will fall between two stools. The poems themselves disappoint this general reader, or at any rate the translations do, their rhythms in particular. Here is the opening of “The Beaten Path” (Le Sentier batu):

It’s foolish to speak scornfully

and talk of things that patently

will make others feel shamed and slighted.

Many examples can be cited

that offer cogent proof of this.

It’s wrong to joke about what is

for real. It’s said and truly known

that you shall reap as you have sown:

The butt of scorn and calumny

will find an opportunity

to strike back. Evil tongues have found

that what goes around comes around.

I cannot hear this.

As the general reader knows, it is in two works by Chaucer that the fabliau achieved its possibilities for us: The Miller’s Tale and The Reeve’s Tale. In her superb edition of The Canterbury Tales, Jill Mann does all that one could ask.3 Take The Miller’s Tale. Kiss me, then, the lover calls up to the window:

The window she undoth, and that in haste.

“Have do,” quod she, “com of, and speed thee faste,

Lest that oure neighebores thee espye.”

This Absolon gan wipe his mouth ful drye.

Derk was the night as pich or as the cole,

And at the window out she putte hir hole,

And Absolon, him fil no bet ne wers,

But with his mouth he kiste hir naked ers

Full savourly, er he were war of this.

Abak he sterte, and thoghte it was amis,

For wel he wiste a womman hath no berd.

He felte a thing al rogh and long yherd,

And seide, “Fy, allas! what have I do?”

“Tehee!” quod she, and clapte the window to,

And Absolon gooth forth a sory paas. “A berd, a berd!”* quod hende Nicholas,

“By Goddes corpus, this gooth faire and wel!”

*A berd, a berd: Since Nicholas [the lodger who is sleeping with Alison, his landlord’s wife] has no way of knowing Absolon’s reaction to Alison’s pubic hair…, A.C. Baugh suggested that his mocking comment alludes to the expression “to make (someone’s) beard,” meaning “to outwit someone.”… J.D. Burnley argues, however, that “the centrality of the narrative events” here displaces psychological realism—that is, the characters are assumed to possess the same knowledge as the reader.

Not, in that case, a bourgeois realist text. Good. And so is Jill Mann’s word gratuitous when we get wind of a later humiliation:

This Nicholas was risen for to pisse,

And thoughte he wolde amenden al the jape:

He sholde kisse his ers, er that he scape.

And up the window dide he hastily,

And out his ers he putteth prively,

Over the buttok, to the haunche-bon.

And therwith spak this clerk, this Absolon:

“Spek, swete brid; I noot noght wher thow art.”

This Nicholas anoon leet fle a fart,*

As greet as it hadde been a thonder-dent,

That with the strook he was almoost yblent.

*The fart is not just a gratuitous obscenity, but a deliberate answer to Absolon’s “speak.” Classical and medieval grammarians defined speech (vox) in two ways: (1) in its physical aspect as “broken air”…(2) in its intellectual aspect as “a sound which signifies according to a convention.” Nicholas’s fart represents the purely physical element of speech, divorced from signification; it answers Absolon’s flowery verbiage with no more than “hot air.”

Howard Bloch says that “the fabliaux make the body speak, and Ned Dubin’s translation makes them speak English.” But not as pungently as does Chaucer’s genius. I remember an exhibition that was called “Safe Art.” Say what?

The body often speaks within fabliaux, where private parts go public, or are thought to:

Women ben full of Ragerie,

Yet swinken not sans secresie.

Thilke Moral shall ye understond,

From Schoole-boy’s Tale of fayre Irelond:

Which to the Fennes hath him betake,

To filch the gray Ducke fro the Lake.

Right then, there passen by the Way

His Aunt, and eke her Daughters tway

Ducke in his Trowses hath he hent,

Not to be spied of Ladies gent.

“But ho! our Nephew,” (crieth one)

“Ho!” quoth another, “Cozen John;”

And stoppen, and lough, and callen out,—

This sely Clerk full low doth lout:

They asken that, and talken this,

“Lo here is Coz, and here is Miss.”

But, as he glozeth with Speeches soote,

The Ducke sore tickleth his Erse- roote:

Fore-piece and buttons all-to-brest,

Forth thrust a white neck, and red crest.

“Te-he,” cry’d Ladies; Clerke nought spake:

Miss star’d; and gray Ducke crieth Quake.

“O Moder, Moder,” (quoth the Daughter)

“Be thilke same thing Maids longer a’ter?

“Bette is to pyne on coals and chalke,

“Than trust on Mon, whose yerde can talke.”

“‘Tehee!’ quod she, and clapte the window to.” “‘Te-he,’ cry’d Ladies.” But, this time, who he? Chaucer, “lately found in an old manuscript”? No, the poet who praised Chaucer as “a master of manners, of description, and the first tale-teller in the true enlivened natural way”: Alexander Pope.

The fabliau was alive in Chaucer, assuredly. And then? “The fabliaux live on in the comic tradition of the West,” we are reminded, and are “the ancestors of the modern short story, especially of the drôle type, those of Balzac, O. Henry, Mark Twain, or Maupassant.” But those are stories at the high end, and it is at the low end that the essential spirit of the fabliau must flourish if at all.

The twentieth century was to enjoy the art, the low art, of Donald McGill, whose comic postcards prompted one of George Orwell’s best feats of cultural criticism. The repertoire was that of the fabliau: crude jokes about sex, marriage, obesity, drink, lavatories. Orwell wrote:

It will not do to condemn them on the ground that they are vulgar and ugly. That is exactly what they are meant to be. Their whole meaning and virtue is in their unredeemed lowness, not only in the sense of obscenity, but lowness of outlook in every direction whatever.

But the art of Donald McGill has long gone. Even the recent teeming exhibition “The Postcard Age” at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, with its capacious catalog, fails to accord a place to such coarse-featured caricatures, though the misogyny that takes pleasure in imagining physical muzzles on women’s faces is hatefully present.4

Where did the spirit of the fabliau manage to live on? In the genius of some particular writers, notably and notoriously Terry Southern, and not only in Candy. And in the genius of a particular form, the limerick. The fabliau had always been more of a situation than of a story, and the limerick contracts the fabliau down to nothing but situation. So the heir to Geoffrey Chaucer, and to his gifted younger brother Dan Chaucer, is Jeff Chaucer, author of A Garden of Erses.5 Anti-clericalism, anyone?

THE MODERN CHURCH

We’re all of us very much struck

By the way our new dean bellows “Fuck!”

It’s his yelling it when

We’re expecting “amen”

That singles him out from the ruck.

(Compare the Archbishop of Canterbury, above.) Or scatology and anticlericalism?

The Cardinal-Bishop of Gaeta

Was a truly phenomenal shiter.

If it’s proof that you want,

He could fill up the font

And still have some left for his mitre.

Misogyny?

I was told by a tycoon who’d known her

Of a girl in Red Gulch, Arizona,

The inside of whose twat

Was so blazingly hot

That it lit his Corona-Corona.

Good perhaps for a laugh (one), but—like all fabliaux—quick to pall.

-

1

Edited by Peter France, 1995. (Crossword clue: 5, 6. But it was not he who said L’état, c’est moi.) ↩

-

2

Edited by Greg Delanty and Michael Matto (Norton, 2011). See my review in these pages, “Mixing Mystery and Ingenuity,” June 9, 2011. ↩

-

3

Penguin, 2005. I must declare an interest; as general editor, I stand to gain a good many cents when a copy is sold. ↩

-

4

Lynda Klich and Benjamin Weiss, The Postcard Age: Selections from the Leonard A. Lauder Collection (MFA Publications, 2012). ↩

-

5

With an introduction by Robert Conquest (Orchises, 2010). ↩