The years leading up to the 2008 election were not a promising time for a liberal politician or a liberal philosopher to seek common ground with conservatives. The country was split, according to the conventional image, between red and blue states, reflecting two hostile cultures and worldviews. In 2004, Karl Rove’s strategy of inflaming those divisions and thereby mobilizing the conservative base had succeeded in reelecting George Bush. It was also by stoking right-wing passions against liberalism that the most powerful voices in the conservative mass media—Rush Limbaugh, Bill O’Reilly, Sean Hannity, Ann Coulter—had built up their audiences. Constructive dialogue with liberals was the last thing on their minds.

Under the circumstances, most liberals weren’t interested in dialogue either. Impatient with the lofty aims and gracious defeats of so many Democrats, they were in a fighting mood, not a reflective one. A popular line of argument among Democratic strategists was that it was time to learn from the other side, get tough, and return fire. Ideas had their uses, to be sure, as weapons in the arsenal of partisan warfare, provided that they were packaged shrewdly—hence the interest in language, “framing,” and “narratives” by such writers as Drew Westen and George Lakoff—but serious debate was not in high demand. Like conservatives, liberals were preoccupied with one problem above all: how to win a majority, if only barely, in what was presumed to be a closely split and highly polarized electorate.

In fact, according to opinion surveys, the American public hadn’t actually become more deeply divided than in the previous several decades; issue by issue, most Americans continued to be bunched closer to the political center than the extremes.1 What had become polarized was the expression of political opinion. As a result of the defection of the white South from the Democrats and the conservative revolution inside the GOP, the two major parties were now more ideologically distinct and antagonistic. And with the rise of talk radio and cable television, partisan mass media had become more important in the news and in public controversy. But far from being happy with intensified partisanship, many voters were disgusted with it and yearned for leaders who could somehow rise above the daily crossfire.

It was part of the genius of Barack Obama’s campaign for the presidency that he was able to respond to this yearning without falling into a bland and muddled centrism, compromising the integrity and force of his own views. During the campaign, Obama blamed partisan quarreling for many of the nation’s troubles and said that neither of the major parties had faced up to its historic responsibilities; but it wasn’t as if his own positions lay somewhere vaguely between the two. His voting record and policy proposals were unmistakably liberal. Instead of adopting a combative position toward conservatives, however, he made a point of meeting with them, listening attentively without necessarily agreeing about what government ought to do. Appearing before large audiences at such venues as Reverend Rick Warren’s Saddleback Church, Obama tried to make it clear that he “got” their concerns, whether about race, religion, or welfare.

In his speeches Obama put much emphasis on the themes of personal responsibility and respect for tradition, as he did later in his inaugural address. But he could consistently hold both those views and also liberal positions on such matters as taxes, health care, civil liberties, and the environment. For years conservatives have attacked liberalism as culturally and morally alien from the world inhabited by most Americans; Obama was showing that he shared the moral concerns of a great many voters.

Yet in interpreting those principles, Dworkin doesn’t pretend to strike a balance between opposing perspectives. He observes at the outset that his own views are “a very deep shade of blue.” Accordingly, his second objective is to try to defend a liberal interpretation of Americans’ shared principles—or as he puts it, to present “a form of liberalism that is not simply negative but sets out a positive program firmly based in what I take to be common ground among Americans.”

Advertisement

Dworkin’s book is not a more general philosophical statement of Obama’s views, though they have some points of convergence on the importance of principles of equality and responsibility. What is most similar about their enterprises is the effort to plant liberalism on common moral ground together with conservatism and to take some of the bitterness out of the air of American public life. Both Obama and Dworkin pursue liberal aims within a vision of a wider democratic partnership that would include conservatives, even if conservatives refuse their overtures.

1.

Dworkin rests his analysis on the claim that there is a broad moral consensus in the United States in favor of two principles of human dignity. According to the principle of the “intrinsic value of human life,” when a life has begun, it matters objectively whether it goes well. “It is good when that life succeeds and its potential is realized and bad when it fails and its potential is wasted.” And according to the principle of “personal responsibility,” each of us has special responsibility for making a success of our lives; we are responsible for finding value in life and deciding what kind of life to lead.

Many people would guess a philosopher to be a conservative if all they knew about him was that his two fundamental tenets concern the intrinsic value of human life and the importance of personal responsibility. But Dworkin has long maintained that these principles underlie his own egalitarian liberalism; at the beginning of his 2000 book Sovereign Virtue, which incorporates more than two decades of his work on the moral foundations of politics, he presents the two principles in almost identical language.2 But although that book and his new one share the same point of departure, they proceed in different directions. Dworkin’s central purpose in Sovereign Virtue is to develop his theory of equality, uphold it against liberal alternatives, and show that, when understood as he proposes, equality is consistent with liberty and other democratic values.

He particularly distinguishes his version of liberal theory from those of Isaiah Berlin and John Rawls. Berlin claims that choices between competing values are inescapable in politics and that equality, in particular, inevitably clashes with liberty, whereas Dworkin argues that equality and liberty should each be conceived in a way that takes the other into account, so that anybody who is committed to one would cherish the other no less. And whereas Rawls, in his formulation of “political liberalism,” seeks to establish a basis for government that does not depend on any comprehensive moral agreement, Dworkin roots his political theory in fundamental moral principles that he claims are widely shared.

Of the three, Dworkin’s approach is, in some respects, the most ambitious. Berlin says that liberal values such as equality and liberty cannot be harmonized, while Rawls says politics and comprehensive moral theories must be insulated from one another. Dworkin, in contrast, puts forward a unified theory of political morality as a plausible goal. And this promise of intellectual and moral coherence has been one of the principal attractions of his work.

While Sovereign Virtue is a densely argued contribution to philosophical debate, Is Democracy Possible Here? is a shorter, more accessible book addressed to conservative challenges in public life. The perspective that Dworkin is defending is the same, but the arguments he wants to overcome are different. From the outset, however, he stipulates that the two principles of human dignity are shared by conservatives and liberals alike.

To be sure, others might frame those principles differently or hold other moral principles equally important, but while Dworkin challenges his readers to come up with alternatives, he doesn’t consider any. For example, the only form of responsibility he considers is individual; there is no discussion here of environmental issues such as global warming or of collective responsibility to future generations. Taking up a series of contentious public issues—terrorism and human rights, the public role of religion, taxation and legitimacy, and the corrosion of democracy—he uses the twin principles of human dignity as his criteria, asking how, for each issue, they should be interpreted and applied. He aims to show what liberalism now stands for and requires.

To some readers, life’s intrinsic value and personal responsibility may seem too abstract to yield definitive conclusions or to claim a moral consensus of any significance, especially since liberals and conservatives differ sharply about their meaning. But just as it matters for law and politics that Americans share a constitution even though they disagree about how to interpret it, so the recognition of common moral principles may help in clarifying and even resolving political disagreements. Rights, Dworkin argues, have a foundation beneath the law, in the conditions of human dignity, and to find the basis of public values in personal dignity rather than, say, in utilitarian principles of collective welfare is a choice of some consequence.

The principles qualify each other. The obligations that the right to equal concern imposes on government depend on the principle of personal responsibility. Although people are not responsible for circumstances beyond their control, they are responsible for their choices, and respect for personal responsibility therefore sets limits on how far government ought to go in pursuing equality. Dworkin’s conception of personal responsibility rules out efforts to compensate people for choices that turn out badly.

Advertisement

Conversely, individual liberty depends on the principle that each life has equal and intrinsic value. Dworkin defines liberty as the right to do what you want with what is “rightfully yours.” But what is rightfully yours cannot be determined independently of all the laws—the property laws, labor laws, tax laws, and so on—that make up what he calls the “political settlement.” And that political settlement must reflect the state’s obligation to show equal concern to individuals under its power. So although Dworkin denies that equality and liberty conflict, he conceives of them in tension with each other. Or to put the point another way, equality and liberty are like simultaneous equations that can only be solved together.

As complex as this formulation is, it effectively anticipates a common line of attack on liberalism by both conservatives and communitarians who claim that liberals focus solely on rights to the exclusion of responsibilities. On the contrary, personal responsibility implies rights, and rights to equality must take personal responsibility into account. But what of the claim that Dworkin’s approach is wholly individualistic, neglecting the values of community and tradition? The principles of human dignity, he points out, are individualistic only in the sense that “they attach value to and impose responsibility on individual people one by one.” They do not imply that an individual can achieve or even conceive success “independently of the success of some community or tradition” to which that person belongs. While individuals must be responsible for their choices, Dworkin says that those who voluntarily defer to traditions or religious leaders are exercising that responsibility. It’s only when communities coerce individuals that they violate the principle of responsible choice.

2.

When Dworkin turns to specific contemporary controversies, his general strategy is to give the argument between the red and blue political cultures a “structure,” as he puts it, by identifying a fundamental theoretical divide underlying the issues in dispute. In evaluating antiterrorism measures, for example, he observes that the usual formulation in assessing legislative and electoral policies is whether there is a “balance” to be struck between rights and security. Conservatives generally say that the government must balance rights against security, and some liberals disagree only in giving more weight to rights. Dworkin’s position, in contrast, is that certain kinds of rights—human rights—cannot be traded off for any possible gain in security, lest their violation (say, through torture) compromise our commitment to the basic conditions of human dignity.

What lends Dworkin’s analysis interest is less the positions that he takes on specific issues than how he arrives at them. In discussing the role of religion in public life, he avoids any suggestion that conservatives are intolerant and instead identifies the central divide as a choice between conceiving of America as a “tolerant religious society” or as a “tolerant secular society.” The first model views the nation as “collectively committed to the values of faith and worship, but with tolerance for religious minorities, including nonbelievers,” while the second sees the nation as “committed to thoroughly secular government but with tolerance and accommodation for people of religious faith.” From the first standpoint, though government cannot favor any particular religion, it can endorse religious belief in general by providing for ecumenical prayer in public schools, incorporating references to God in public ceremonies, oaths, and justifications of public decisions, and punishing practices such as homosexuality that the religious majority sees as violating God’s will.

By contrast, the second standpoint insists, as Dworkin conceives it, on the principle of personal responsibility, which requires the state to afford individuals the ethical freedom to define value in their own lives. That requirement prevents the state from using its power to favor faith over nonbelief or to punish practices of a minority on the basis of religious convictions. He argues unequivocally that those who celebrate the traditions of marriage and family life should not deny the accumulated experience and benefits of those traditions to homosexuals who want to marry.

Dworkin’s theory of taxation is derived from his core principles of equality and responsibility. Some radical egalitarians believe that government should seek to equalize wealth or satisfaction, but Dworkin rejects any kind of equality of outcomes on the grounds that individuals should be responsible for their choices. According to Rawls, justice requires arrangements that make members of the worst-off group as well off as possible; but Dworkin rejects that position too because it fails to distinguish between those who are poor by virtue of their circumstances and those who are poor by virtue of their choices and therefore also “cuts the connection between personal choice and personal fate that the principle of personal responsibility requires.”

Instead, Dworkin proposes as an ideal that “a community treats citizens with equal concern when its economic system allows them genuinely equal opportunities to design a life according to their own values.” On that theory, government should seek a certain level of ” ex ante equality” of resources, that is, law and policy should put people on equal footing prior to the decisions that they make about work versus leisure, investments, or other matters in which they have some choice.

But how far should government go in trying to achieve this kind of equality? Here drawing on an insurance model, Dworkin argues that government policies should compensate for disadvantage to the extent that rational individuals would have insured themselves against risks of bad luck, had they been equally capable of doing so. (“Bad luck” in this context includes bad genetic luck such as not having marketable talent.) The insurance metaphor has its rhetorical advantages, but it introduces a complex hypothetical procedure. In thinking about taxes, Dworkin says, we should ask

what level of insurance of different kinds we can safely assume that most reasonable people would have bought if the wealth of the community had been equally divided among them and if, though everyone knew the overall odds of different forms of bad luck, no one had any reason to think that he himself had already had that bad luck or had better or worse odds of suffering it than anyone else.

As a philosophical device to suggest what choices people would make behind a “veil of ignorance,” the insurance device offers a useful and provocative way of thinking about taxes. But we have no way of determining and cannot “safely assume” how much insurance at what cost, even at a minimum level, individuals would buy under these imaginary conditions. Public finance experts, confronted with Dworkin’s questions about the level of insurance people might buy, could not determine whether our taxes are too high or too low. Dworkin’s own inference is that because the insurance would be expensive, “buyers would try to keep the real cost of the premiums—the impact of paying the premiums on their expected well-being—as low as possible.” Although buyers could limit that impact by paying premiums through a progressive income tax, the implication is that the system would not be overgenerous. Indeed, Dworkin observes, “the insurance device is a safety-net device,” albeit “a principled safety net.”

But safety-net policies may be guided by another moral principle, the alleviation of suffering. American social policy distinguishes insurance programs like Social Security, which operate more or less on the logic that Dworkin proposes, from safety-net programs, like welfare, which provide a minimum level of assistance to people even if the cause of their adversity is their own bad choices. A split system of this kind could remedy the failure in Dworkin’s approach to provide a backstop for people whose poverty is the result of their own irresponsibility.

3.

Most contemporary poverty in America, in Dworkin’s view, is the result not of the irresponsibility of low-income people, but of circumstances and policies beyond their control. Indeed, as he sees it, the failure of the government to show equal concern for the poor is so serious that it threatens the legitimacy of American democracy. At the beginning of Is Democracy Possible Here?, the title seems to ask whether Americans can have the kind of public argument that democracy requires. But later the question takes on an even darker meaning: Is the United States failing to meet the minimum moral standards of democracy?

Again, Dworkin identifies a central conceptual divide, this time between a “majoritarian” and a “partnership” conception of democracy. The first sees democracy as majority rule pure and simple, while the second envisions a political enterprise in which all citizens, including those in the minority, are full partners. Hardly anyone who writes about democracy would disagree that it requires not just elections, but also protections of basic civil and political rights such as freedom of speech. Without those guarantees the public would lack the independent capacity to assess political issues and to hold government accountable. But Dworkin’s conception of partnership democracy goes further, insisting that the decisions of the majority are not democratic if they steadily ignore “the interests of some minority or other group” or fail to cultivate the mutual respect that a democratic partnership requires.

The crux of the problem is that the majority in a democracy may not accept the obligations—to pay taxes, for example—that come with Dworkin’s twin moral principles. It would be inappropriate, he acknowledges, to expect individuals in their private lives to show all members of a society equal concern; people legitimately show more concern for their family and others who are close to them. But what about the moment when these same people vote?

Although Dworkin never addresses the problem directly in his new book, he is explicit about it in Sovereign Virtue:

A political community that exercises dominion over its own citizens…must take up an impartial, objective attitude toward them all, and each of its citizens must vote, and its officials must enact laws and form governmental policies, with that responsibility in mind.3

But to expect voters to be “impartial” and “objective” is plainly unrealistic. Dworkin needs some other source of legitimate authority to protect the interests in equal concern, and he assigns that role to judges. The judiciary, however, cannot levy taxes, nor can it intervene in all the political decisions that affect distributive justice without overburdening the courts and provoking a political backlash. Dworkin may be right about the limitations of majority rule; the voters aren’t always wise, much less impartial. But if a political philosophy cannot command a majority in elections, it will ultimately lose sway over the courts too. Majority rule is not all there is to democracy, but it cannot be dismissed.

So, besides relying on judges, Dworkin also wants to reform the political process, which in his view has become thoroughly debased. Money has corrupted elections, commercials have degraded them, and studies show that many Americans lack rudimentary information about national issues. On the majoritarian view, he says, the “degraded state of our political argument” does not count as a serious problem, but on the partnership view it does count “because mutual attention and respect are the essence of partnership.”

In addition to limits on campaign spending, he calls for high school courses on political philosophy, “two special public broadcasting channels” —both with equal-time requirements for major candidates—“to offer continuous election coverage during each presidential election,” and regulations of private broadcast stations requiring that ads for candidates be at least three minutes long with the candidate “speaking directly to the camera” for two minutes. Serious high school courses in political ideas—not just in “civics”—might eventually have useful effects on American politics if schools would adopt them. But have we had a shortage of election coverage that justifies two (why two?) dedicated public channels? In the age of cable and the Internet, would those channels or regulations on the length of ads make much of a difference?

Of course, a critical factor in 2008 was the intelligence and tone that Obama brought to the campaign. Americans, it turned out, would respond to a candidate who talked to them thoughtfully. (When she withdrew from the campaign, Clinton also rose to a very high level, giving a speech of genuine distinction.)

One crucial aspect of the tone that Obama set was a kind of rhetorical nonviolence, a spirit of comity and calm reason that he displayed in the face of attacks and when he addressed conservatives. In setting a higher standard for public argument, emphasizing common moral ground, and holding to his liberal convictions, Obama reflected the same impulses that move Dworkin. But as a political leader, he was able to do something that philosophers generally cannot expect to accomplish, translating those impulses into a successful majoritarian politics.

The qualities Obama displayed in the campaign have become all the more important now that he has become president at a time of national crisis. In the early days of his administration, his efforts to appeal across party lines were quickly pronounced a failure when no Republicans in the House and just three in the Senate supported his stimulus plan. But Obama’s success in reaching across the red–blue divide should not be measured in congressional votes. Early in their presidencies, both of his immediate predecessors became the objects not merely of opposition but of contempt, and that kind of virulence could be even more threatening to the country as economic stress increases. If Obama can hold on to the respect of the opposition and encourage many others to keep an open mind, he will have done more than Bill Clinton or George W. Bush did. Despite the lack of Republican support for most of his program, the President’s interest in giving his administration a bipartisan cast seems undiminished. In quick succession in May and June, he named prominent Republicans to be secretary of the Army, ambassador to China, and chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The realistic aim of efforts to transcend partisan divisions is not to win over the likes of Rush Limbaugh and Sean Hannity, but to isolate them, and ultimately to persuade enough Republicans that playing to their hard-core base is a strategy for making their own party irrelevant. Liberals have a stake in the kind of conservatism that flourishes in America—they need to make it more open to persuasion and partnership. Republicans will vote against Obama’s major proposals, but he may nonetheless persuade them gradually not only to change their tone but to seek out common ground as well. If they have any inclination to think about that common ground philosophically, they might consider the moral principles Dworkin proposes as a useful ground for creative disagreement.

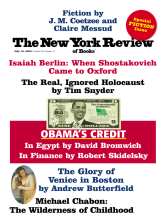

This Issue

July 16, 2009

Advice to the Prince

-

1

See Morris P. Fiorina, with Samuel J. Abrams and Jeremy C. Pope, Culture War?: The Myth of a Polarized America (Pearson Longman, 2005; second edition, 2006). ↩

-

2

Ronald Dworkin, Sovereign Virtue: The Theory and Practice of Equality (Harvard University Press, 2000), p. 8. ↩

-

3

Sovereign Virtue, p. 6 (italics added). ↩