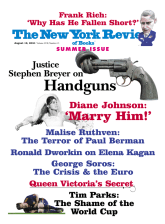

Reading the first three of these books about marriage, you might be tempted to reflect that there’s nothing new under the sun. Books of advice about finding love and keeping it have been around, offering formulas and nostrums to readers and believers, since the beginning of print, and so have statistics about the demise of marriage. But Committed and Marry Him, the two books by Elizabeth Gilbert and Lori Gottlieb, suggest that what is new is the mindset of the intended readers. What do we take from the new sensibilities of today’s authors and readers, the thirty-somethings weighing these age-old issues? Has anything really changed?

This reviewer should probably disclose at once that there is much in the day-to-day concerns of the mate-seeking world of today completely outside her experience, which is that of someone who has been married since her teens, and has many children and zero experience of relationship coaches, Internet matchmaking, speed dating, or the worlds of office work, therapy, singles bars, and biological clocks that are the new realities. I even took the very college course (required for incoming freshmen) with the very professor derided by Betty Friedan in The Feminine Mystique and mentioned here by Elizabeth Gilbert as epitomizing the era of unreconstructed females on the cusp of risen consciousness. (Of the class, “Marriage and the Family,” I remember only that when our group of inexperienced teenagers expressed reservations about male anatomy, Dr. Henry Bowman reassured us that, among other things, the penis was actually a lot cleaner than the vagina, being so much more often exposed to soap.)

It used to be that on a date, the boy would pay for a Pepsi and the movie; that was it. Lori Gottlieb, in Marry Him: The Case for Settling for Mr. Good Enough, estimates the cost to today’s woman of four months of dating, counting therapy afterward when it doesn’t work out, to be $3,600: online dating service, clothes, including expensive underwear, haircut, hair color, cosmetics, bikini wax, entertaining him, and gifts. Things have changed.

1.

First, some statistics to frame the discussion. Marriage is a “public, formal, lifelong commitment to share your life with another person,” as Andrew J. Cherlin defines it in The Marriage-Go-Round: The State of Marriage and the Family in America Today. In the American view, marriage remains the ideal state: only 10 percent of Americans endorse the idea that the institution is outdated, compared to, say, in France, where a third of people think it is. On the contrary, America is seeing a sort of Marriage Renaissance, the impetus for which comes in part from the gay marriage movement, which in itself reflects our reverence for weddings. All the usual explanations for the marrying nature of Americans seem good enough: marriage is seen as a haven in a rough world, an antidote to rootless anomie unneeded by people in smaller, more comfortable societies, and it developed in response to other historical factors including patterns of life and religion in Colonial America and on the frontier. Cherlin also says that marriage is not an innate biological impulse but a socially determined convenience for raising children.

By the time they’re forty, 84 percent of American women have been married, a higher percentage than in other Western nations; and more than half (54 percent) of marriages will have broken up within fifteen years. About the same percentage of “cohabiting relationships” will have broken up even sooner. Americans divorce more often than others do and have more partners, more children out of wedlock, and more abortions.

Along the way, a total of 90 percent of women, almost all of them, will have one partner or more during their lives, and some many, many more.1 If hypocrisy, as some suspect, is our most salient national quality, Cherlin finds lots of examples in the inconsistency of American religion and law, the one urging us with increasing shrillness to fidelity in sickness and health, the other extending legislation for no-fault divorce. No doubt American piety and reverence for marriage have their origins in our national psyche for religious and other reasons that Cherlin outlines—but in practice, religious communities often have a high rate of divorce. The Bible-belt state of Arkansas has the second highest in the nation, after Nevada. Fundamentalist Christians have a somewhat higher divorce rate and higher turnover of live-in partners, maybe because this group also tends to have less education and lower income. The divorce rate among college-educated people has actually fallen in the past two or three decades.

Cherlin believes that the fragility of the American family is the result of an evolution—an “upheaval”—since the late 1950s, from earlier traditions governing property, progeny, prestige, duty, and God, to a new view that marriage is a “right” on the path to personal fulfillment: “It is about personal growth, getting in touch with your feelings, and expressing your needs. It emphasizes the continuing development of your sense of self throughout your life.” He links this changed view to the civil rights movement and Vietnam, and to the “prosperity and progress of the 1950s.” He also mentions, but probably seriously underestimates, the liberating effect of the pill. Better contraception seems enough in itself to explain the mutation in women’s attitudes. Once liberated by family planning to enter the job market, they gained, along with the ability to earn money, the independence to leave marriages that were run on terms that no longer seemed acceptable. It must also affect marriage rates by removing one incentive for marriage—unplanned pregnancy.

Advertisement

Cherlin, a professor of sociology and public policy at Johns Hopkins, is mainly concerned to study the impact on children of divorce and serial partnering; fully 40 percent of American children will “experience the dissolution of their parents’ intimate partnership” by the time they’re fifteen, a higher figure than in other Western countries except New Zealand.

Cherlin wants to make the point that children of divorced parents are just as well off with one lone but stable parent, but are far less well off when the custodial parent—usually the mother—has a series of temporary partners, or, more surprisingly, even if she remarries, given the likelihood that that marriage will break up too. He believes that efforts to reenergize traditional marriage aren’t going to work because the notion of marriage has changed. From an arrangement meant to foster the rearing of children it has come to be seen as “a private relationship centered on the needs of adults for love and companionship.” In drawing some inferences for public policy, he suggests exploring ways of helping single parents financially, but he acknowledges the difficulty in today’s moralistic legislative climate of doing this without seeming to commend unwed parenthood.

2.

How do single people find partners in our fluid, urban world? One way, used by millions, is to sign up for one of the many matchmaking sites on the Internet (eHarmony.com, Match .com, Chemistry.com, JDate, Spark, and dozens of others). With many of them, you take a test, list your requirements, describe yourself, and of course pay. While some rely on your basic demographic data like age and whereabouts, others give you a personality test, and the questionnaires designed to match you up with other people are the work of such consultants as Dr. Helen Fisher, a research professor of anthropology at Rutgers, author of self-help books, including Why Him? Why Her?, aimed at helping people understand their own basic personalities and predict the types of people they’ll get along with.

Her analyses of academic studies and nearly 40,000 responses on Chemistry .com to a questionnaire she reprints in this book have led Fisher to propose a set of four fundamental personality types she calls Explorer, Builder, Director, and Negotiator, distinctions that resemble those in many other morphological systems we’ve all heard of: introverts and extroverts; Types A and B; the Humors—still used in homeo-pathy—Sanguine, Bilious, Lymphatic, and Nervous; endo-, ecto-, and mesomorphs; the classic Air, Earth, Fire, and Water; Ayurveda; the Chinese 5 Elements; the zodiac; and many others reaching back to the mists of time, referring to body types, psychological tendencies, character, or fate. The most influential modern personality inventories usually rely on a well-established one, the MBTI, developed to help with personnel placement during World War II, by Katherine Cook Briggs and Isabel Briggs Myers, who in turn relied on C.G. Jung’s typological system of introverted or (Jung’s spelling) “extraverted” thinking, feeling, sensing, and intuiting personalities.2 Fisher relies on them too—as do many modern personnel departments, and even the Pentagon.

These systems propose that each of us has a predominance of traits assigned to one of the categories, with an admixture of others, and according to our basic “type”—really temperament or personality—we’re advised that we’ll get along with some categories of people better than with others. For instance, Builders have a lower divorce rate when married to other Builders than to other types. Fisher finds some evidence, too, that our basic types are determined in utero by the hormonal influences of testosterone, estrogen, dopamine, or serotonin, and extrapolates from other physical traits, for instance the crypts and furrows of the iris: “People with more furrows are more impulsive…. Individuals with more crypts…are more trustworthy, warmhearted, and tender.”

Fisher tells us that she herself is an EXPLORER/Negotiator, and you can find your own type, on the basis of her fifty-six item test that begins, “I find unpredictable situations exhilarating. Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Agree, Strongly Agree,” and includes such statements as “Regardless of what is logical, I generally listen to my heart when making important decisions,” “I have a vivid imagination,” and “I have more energy than most people.” The basic flaw or weak point of such instruments hardly needs pointing out: they all rest on the assumption that we ourselves are good judges of how we behave and feel, and are sensitive to the degree we feel it: very strongly, strongly, somewhat, only a little, not at all? My “only a little” may be what someone else would call “strongly.”

Advertisement

Luckily for us, my husband and I hadn’t taken the test forty years ago, for we wouldn’t have progressed beyond the initial e-mail; Directors (John) and Explorers (me) have a bad record together. Using Internet psychometrics as tools for really deciding whom to marry seems haphazard, even silly, and Fisher’s advice banal and obvious: “Know and like thyself,” “Seek a partner with whom you can be naturally compatible,” “Build connections with a new partner in natural ways,” and so on. Still, Internet dating does provide an occasion, a name or two, and a procedure for getting to know distant people who wouldn’t come your way in real life. Unfortunately if my tentative attempt on eHarmony is typical—I filled in the questionnaire and took it up to the moment I’d have to pay—all I had to show for it were a few e-mail addresses and a blizzard of spam.

While Fisher’s credibility as an academic researcher may be a little undercut by the pop-psych format of her book, and by clumsy or obvious sentences—like “Nature has played her primordial melody, and this new person in your life has slipped easily through your funnel of cultural and biological criteria”—the appendix and notes are more convincing, as is a compendious bibliography of academic work in the field of matchmaking. It’s too bad that she doesn’t include the data from her own analysis of the Internet responses on which she bases her system, which she says she’s writing up for publication later. Regardless of intellectual rigor, or lack thereof, Fisher’s research, and similar work, are in wide practical use, so we must hope they have at least an intuitive relevance.

This is important because, according to the Pew Research Center, “among the relatively small and active cohort of 10 million internet users who say they are currently single and looking for romantic partners, 74 percent say they have used the internet…to further their romantic interests.”3 Nearly a third of American adults say they know someone who has used a dating Web site (many of which make no use of personality tests, simply allowing members to post profiles that others can use to contact them), and about thirty million people say they know “someone who has been in a long-term relationship or married someone they met online.” Though sites like Chemistry.com are a far cry from being a substitute for the intuitive community-based figures who bring together Indian couples, for example, the Web is a social tool that has to be taken seriously.

3.

Lori Gottlieb is a single mother whose article in The Atlantic magazine (March 2008), with the same title as her book—Marry Him: The Case for Settling for Mr. Good Enough)—“went viral” on the Internet. “It’s hard to recall an article that generated so much attention (read: rage) so quickly,” wrote Glynnis MacNicol in Mediaite .com. Gottlieb’s underlying assumption is that every girl wants to get married; and the statistic that 90 percent of American women do get married at some point—a higher percentage than in any other country—supports this.

The audience for Gottlieb’s reflections was vast because about half of American women over fifteen are single, dramatically more than in earlier decades. To take another statistic, whereas in 1975, 90 percent of women were married by the time they were thirty, in 2004 “only a little more than half were,” suggesting a huge audience of unmarried people who may be interested in her views about giving up on the idea of a perfect mate and settling for Mr. Good Enough, someone whose personal qualities aren’t quite up to your original specs but who may turn out to more than compensate with good points you’d overlooked.

Gottlieb thinks that she and other unmarried women in their thirties or older have gotten unrealistic notions of life and men, and are just too picky. Besides requiring that a guy be tall, have intelligence, education, kindness, a good income, and hair, he has to have an instant spark and avoid off-putting quirks like the wrong taste in TV programs or clothes. Her view that women have to learn to look for the good qualities of men who may not fit with their exigent dream lists, but with whom they know they get along, is exactly the advice mothers have always given daughters, but was somehow not transmitted to Gottlieb’s generation.

Young women’s ideas, incomes, and role models (conspicuously, the characters in the television series Sex and the City) have led them to demand too much in a marriage partner, just as risky for remaining unmarried now as it was in the days of Jane Austen or Fanny Burney. (Does Sex and the City reflect reality or create it? Another blogger, Meg Hemphill in The Huffington Post, called one of its writers, Michael Patrick King, “the premiere social documentarian of our time.”) Gottlieb and her readers do seem a lot like Carrie, Miranda, Charlotte, and Samantha, mistaking a life of great clothes and consequence-free sex for the real world. The viewers seem not to notice that the four TV heroines experience the same forms of anguish as did Elizabeth Bennet in the nineteenth century, or anyone in high school in any era. Will he call? Is my dress okay?

Carrie Bradshaw and her friends, like Lori Gottlieb and her friends, seem to talk about men the way men have been accused of talking about women: as tens or hotties or nerds rather than as individual, imperfect mixtures of qualities, needs, wants. One could add that though there’s lots of sex in the television series, there isn’t much about it in any of these books, especially when compared to the marriage manuals of the 1970s and 1980s, when it was thought that sexual compatibility was the first key to saving a marriage. Then, it was all whipped cream and maid’s uniforms and discussions about clitoral, vaginal, and simultaneous orgasms, things that hardly come up here, maybe because “good” sex didn’t prove the whole answer, or maybe it’s now a given. Certainly any man watching Sex and the City will have learned a few discomfiting things about what women think about male performance, whether size matters, and much else. But the message, as in Jane Austen, is that to be single is to be humiliated and that, above all, you mustn’t end up alone. It’s Pride and Prejudice meets Debbie Does Dallas.

Like Carrie and her friends, Gottlieb has the new candor and a dash of cynicism: “Marriage isn’t a passion-fest; it’s more like a partnership formed to run a very small, mundane, and often boring nonprofit business. And I mean this in a good way.” “So what if Will and Grace weren’t having sex with each other? How many long-married couples are having much sex anyway?” Gottlieb includes herself among those who have made the error of being too choosy. Readers who have followed her career through her other pieces in The Atlantic will also know that she had a sperm-bank baby:

Each time I read about single women having babies on their own and thriving instead of settling for Mr. Wrong and hiring a divorce lawyer, I felt all jazzed and ready to go. At the time, I truly believed, “I can have it all—a baby now, my soul mate later!”

Ever a perfectionist, she gets a bikini wax for her implantation appointment at the fertility clinic.

In another issue she investigated and reported in depth on Internet dating, including the work of Helen Fisher, of Why Him? Why Her?, who explained her ideas about compatibility to Gottlieb as

a constellation of factors…. Sex drive, for instance, is associated with the hormone testosterone in both men and women. Romantic love is associated with elevated activity of the neurotransmitter dopamine and probably also another one, norepinephrine. And attachment is associated with the hormones oxytocin and vasopressin. “It turns out,” [Fisher] said, “that seminal fluid has all of these chemicals in it. So I tell my students, ‘Don’t have sex if you don’t want to fall in love.'”

It seems worth noting that Gottlieb’s injunction to take a second look at people you might have dismissed at a younger age contradicts the third of Fisher’s key advice points: “Be confident about your first impressions.”

She gives lots of examples of her regretful friends, one of whom, Jocelyn, is typical of the exigent new woman. Jocelyn tells her,

I know that life is imperfect. But I just know that I require a certain emotional depth and insight in a guy, and if I can’t be with someone who truly appreciates my nuances, I’m not going to be interested in the long-term.

Of course we know that Jocelyn is doomed to solitude. “I require” is the kind of phrase that in fairy tales bad queens and stepsisters are punished for using, and “my nuances” is a phrase that has no female literary equivalent that I can think of.

Gottlieb and her friends are experts in self-definition, veterans of encounter groups, dating counselors, and those Internet questionnaires. She tries Internet dating, matchmakers, date counselors, and more, but she and her friends can’t quite give up their bottom line requirements. Maybe they should simply be encouraged to redefine female success, decoupling it from marriage.

Gottlieb’s story so far has no happy ending. She quotes Goethe: “A confusion of the real with the ideal never goes unpunished.” But you have to wonder whether, at some level, Carrie and Samantha, Lori and Jocelyn prize more than they know the independence that lets them run their own lives.

4.

Elizabeth Gilbert’s Committed: A Skeptic Makes Peace with Marriage has to be read in the context of her earlier book, a mega-best-seller entitled Eat, Pray, Love: One Woman’s Search for Everything Across Italy, India and Indonesia, an almost parodic version of a classic spiritual autobiography, in which she prays about what to do about her unhappy marriage, passes through dark nights of the soul, and comes out stronger and more affirmative, though she never has cause for doubt, as her occasional petitions directly to God are answered promptly and positively. Her first prayer begins: “Hello, God. How are you? I’m Liz. It’s nice to meet you…. Please tell me what to do,” and is answered with instructions: for now go back to bed.

That Eat, Pray, Love was such an enormous success suggests the readerly appeal of a quirky free spirit with a direct and often funny writing style, but mostly of the escapist charm of her adventurous life as an unapologetic seeker to fulfill her somewhat omnivorous needs—to start over; learn Italian in Rome while eating all the gelato she wants; develop some spiritual resources with a guru in India; mess about in Bali; and fall in love. In that she doesn’t seem to be weighed down by money problems or too rigorous a sense of time, and is clear about never wanting children or to marry again, thereby removing realities that may mar most women’s fantasies. She is a sort of superwoman enacting the ideal escape from reality.

However, at the end of that book she Meets Someone, rather as in the final episode of a television series, prefiguring a season to come. Now, in Committed: A Skeptic Makes Peace with Marriage, we pick up where the earlier book left off. Their marriage plans are impeded by her Brazilian fiancé Felipe’s immigration problems, so she has new reasons for exotic travel—waiting in Bali for the US to give him a visa—and also the repose in which to write an intelligent history of marriage, summarizing its paradoxes, beginning with her grandmother’s remark that “the happiest decision of her life was giving up everything for her husband and children.”

It doesn’t escape her that Grandma then says “—in the very next breath—that she doesn’t want me making the same choice.” Similarly her mother, young in the 1950s, talking about her happier, recent empty-nest years, adds, “There are times when I refuse to even let myself think about the early years of my marriage and all that I had to give up.” The fact that marriage is better for men than for women is called by sociologists the Marriage Benefit Imbalance, the well-known “freakishly doleful conclusion” that married women don’t live as long, accumulate as much wealth, thrive professionally, or remain as healthy as unmarried women, and are more likely to die a violent death. Under those conditions, who would want to get married?

After reviewing the disadvantages of marriage and its somber history, Gilbert decides to give it another try, but on her own terms:

Felipe and I have one of the most easygoing relationships you could possibly imagine, but please do not be fooled: I have utterly claimed this man as my own, and I have therefore fenced him off from the rest of the herd. His energies (sexual, emotional, creative) belong in large part to me, not to anybody else—not even entirely to himself anymore. He owes me things like information, explanations, fidelity, constancy, and details about the most mundane little aspects of his life. It’s not like I keep the man in a radio collar, but make no mistake about it—he belongs to me now. And I belong to him, in exactly the same measure. Which does not mean that I cannot go to Cambodia by myself.

What are we hearing here? The free spirit has suddenly begun to sound a bit like Medea, or at least like a traditional husband. Have women finally achieved unisex consciousness? But this is the moment when, if Elizabeth Gilbert were a heroine of fiction, we wouldn’t find her sympathetic. Readers would complain that she was self-centered and riding for a fall, for fiction is slow to abandon the codes embedded in our literary traditions even when they may have changed in life. We are conditioned to read haughty phrases like “he owes me” and “he belongs to me” as predicting misfortune. But fiction always totters belatedly after life, and life must lead the way with courageous spokeswomen like Gilbert—candid, modern in her expression of her “needs” and her enjoyment of perfect freedom. Still, we’ll see how things work out.

In Marriage and Other Acts of Charity, Kate Braestrup, a widowed and recently remarried, youngish Unitarian minister, is enthusiastic about the institution of marriage and gives what we can take as a traditional defense, together with personal anecdotes and tasteful biblical citations—the very book to give to a newlywed, Christian-leaning couple: marriage isn’t easy but can lead to personal growth. Gone are injunctions we might have expected from earlier religious counselors—patience, altruism, self-sacrifice.

Looking back on a rough patch in her first marriage, Braestrup writes:

In retrospect it’s hard to see how Drew [her first husband] had earned my putatively feminist scorn. He did half the housework. He spent virtually all of his nonworking hours with his children, while his working hours, however interesting and “fulfilling” the job was, could be both exhausting and hazardous.

Yet she wants a divorce, he joins a men’s group to talk about anger issues, they “work” on the marriage, ultimately arriving at a traditional definition: marriage is “a relationship of sexual and reproductive exclusivity, companionship, and affection…undergirded by old rules and venerable social conventions, one that confers practical strength and well-being” and is also “peculiarly equipped to promote spiritual growth”—this last observation linking her to her generation in seeing the enterprise in part as fostering the individual’s personal fulfillment. A diminishing number of women are following Braestrup’s conventional marital path, but she is like the renegades in her expectations; self-expression has, it seems, been incorporated into even the most traditional views.

One is stuck by the similarity of the voices in the four of these books written by women: Braestrup, Fisher, Gottlieb, and Gilbert. All four use personal examples about themselves, their moms, or friends, or distant Hmong wives, with what seems to be a publisher-ordained relentlessness, instead of more colorless, but perhaps more demanding, plain old-fashioned expository prose. The new rhetoric of self-disclosure and interaction, the Oprah mode, uses the word “I” or puts a rhetorical question in nearly every sentence so that you the reader are implicitly invited or hectored to have a response: “I know, I know—I ruled out a guy because he’s too attractive. Could I be any pickier?” asks Gottlieb. “So, how do I square this?” “But how do I know for certain that I will never again become infatuated with anybody else?” asks Gilbert. “Do you see a pattern here?” Her passages of self-analysis are presented with a sense of authority that would have startled, say, Simone de Beauvoir, who remarked in a more impersonally general way that “women who know how to create a free relation with their partners are in truth rare; they themselves forge the chains with which men do not wish to burden them.”4

The relentless use of “I” suggests that what may have been lost in the solipsism of recent American culture is an elementary sense of others, male or female. But it’s also possible that this is merely a correction, and that a touch of egotism and sense of entitlement, too lacking in poor, plain Jane Eyre, represents a healthy rebalance, egotism to be apportioned equally between the two sexes.

In overviews of the twentieth century, will we be able to pinpoint a date or event that definitively symbolizes the huge change in at least Western female psychology, from relative comfort in traditional marriage-oriented and dependent roles—though these are always under discussion and redefinition—to today’s transitional and conflicted, egalitarian or even masculinized ideas about breadwinning, career, independence, and self-determination: Mom works, and Dad helps change diapers? If today the object of marriage has become self-fulfillment, a change from earlier models of convenience, sacrifice, and reproduction, Gilbert finesses the reality checks on women’s psychological evolution imposed by having children, a conflict she discusses sensitively and, recognizing the sacrifices of motherhood, resolves for herself by deciding not to have any.

On the whole, the subject of motherhood is either beyond the scope of the above books or secondary to their concerns about marriage and self- fulfillment. Gottlieb, who has chosen single motherhood, has doubtless discovered the relative lack in America of child care for working mothers, a situation that improved during the 1990s and is now suffering with the budget cuts imposed on many states, causing low-paid women to lose badly needed jobs because they can’t afford child care during the day. Andrew Cherlin implicitly endorses child care in the interest of helping single mothers avoid unfortunate choices of a partner. Child care not only helps working mothers but can be seen as supporting child development, with benefits for the society as a whole—possibly a way of looking at the issue without invoking the implicit censoriousness with which working mothers are still often regarded in some societies, especially Germany, the UK, and the US.5

Despite herself, Elizabeth Gilbert gets married in the old-fashioned way, with friends and her mom around, and with toasts, vows, hopes. Like Braestrup she reflects that “marriage is not an act of private prayer. Instead, it is both a public and a private concern, with real-world consequences.” In her earlier Eat, Pray, Love she had thought

about the woman I have become lately, about the life that I am now living, and about how much I always wanted to be this person and live this life, liberated from the farce of pretending to be anyone other than myself…. The younger me was the acorn full of potential, but it was the older me, the already-existent oak, who was saying the whole time: “Yes—grow! Change! Evolve!”

That evolution brought her closer to a traditional understanding of marriage but had not altered in her the changes, from women defining themselves as daughters or partners to experiencing themselves as autonomous individuals who may be someone’s partner and someone’s parent, on terms they themselves are responsible for choosing, the way, presumably, men are used to doing. Who knows if this is a permanent alteration? Collective sensibilities see cyclical changes, the bolder flappers of the Twenties retiring into the docile Fifties generation, forward to the experimental Sixties, and on; weddings and birthrates fluctuating according to the mysterious drives of history. Enabled principally (most think) by better education and contraception, the direction for women has been steadily toward more autonomy, self-confidence, skills, and income, while some individuals are caught in the confusion.

This Issue

August 19, 2010

The Crisis & the Euro

-

1

See M.D. Bramlett and W.D. Mosher, “Cohabitation, Marriage, Divorce, and Remarriage in the United States,” Vital and Health Statistics, Series 23, No. 22 (July 2002). (84 percent, according to Cherlin.) These rates are drawn from the National Survey for Family Growth, part of the National Division for Health Statistics, but include only women from ages fifteen to forty-four years. We can assume the somewhat higher figure by including older age groups among whom marriage is common—or perhaps around 90 percent. Lori Gottlieb quotes the US Census figure that “one-third of men and one-fourth of women between 30 and 34 have never been married,” a number four times higher than in 1970 and a number possibly more germane to her subject. In general, because of differences in the populations sampled, it’s hard to get reliable overall figures, hence the generally used 50 percent divorce rate which may be lower for, say, white urban dwellers than for African-Americans, and is declining, as noted, among the college-educated. ↩

-

2

John Beebe, Analytical Psychology: Contemporary Perspectives in Jungian Analysis, edited by Joseph Cambray and Linda Carter (Brunner Routledge, 2004), pp. 83–115. ↩

-

3

See Mary Madden and Amanda Lenhart, “Online Dating,” Pew Internet and American Life Project, March 5, 2006. ↩

-

4

The Second Sex, p. 751. Beauvoir’s masterpiece is at last available in an unabridged edition in English: The Second Sex, translated by Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier (Knopf, 2010). ↩

-

5

See Peter S. Goodman, “Cuts to Child Care Subsidy Thwart More Job Seekers,” The New York Times, May 23, 2010. For a discussion of European child care policies, see Linda Hantrais and Marie-Thérèse Letablier, Families and Family Policies in Europe (Longman, 1996). ↩