“The only works of art America has given are her plumbing and her bridges.”1 The line dates from 1917: it concluded Marcel Duchamp’s riposte to the New York exhibition committee that had turned down Fountain, his submission of a signed urinal. The objection that his alter ego “Mr. Mutt” had plagiarized the work of sanitary engineers was “absurd,” Duchamp protested in a little review he edited. Introducing his new art of the “readymade,” he claimed that it lay in choosing “an ordinary article of life” and creating “a new thought for that object”; and in later glosses, added that he had opted for an object as “ordinary” as possible, the better to effect that mental transformation.

Yet his statement’s closing quip makes it clear that his choice of item was carefully attuned to its moment. The exhibition in question would be New York’s biggest international art display since 1913’s famous Armory Show: there would be great expectations of Duchamp, as the painter of that show’s runaway success, Nude Descending a Staircase. How could he most wittily escape the inanity of any such public role? Through a taunting, backhanded salute to his host nation’s “only” art—its sublimely nonaesthetic engineering.

The streamlined, the sleek and sinuous: these, for several generations of Europeans, formed a look associated with America, the history-free land. The instincts guiding Duchamp when he purchased his shiny new plumbing ancestrally relate to those of the French state saluting its fellow republic when it shipped Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi’s clean-planed, blandly imperturbable Statue of Liberty across the Atlantic in 1885. The most poetic expression of those instincts, however, would come some seven decades later from a peculiarly obsessive disciple of Duchamp’s. During the late 1950s the British artist Richard Hamilton devised a succession of four-foot-high panels with half-playful, half-programmatic titles such as Hommage à Chrysler Corp. and $he.

This body of work brought together eros and Eisenhower-era modern design in a rapturous, spooky dream. In Hommage, a D-cupped showroom-window divinity caresses chrome bodywork; in $he, a similarly curvaceous presence revels in the embrace of an opened refrigerator. Hamilton conjured up these archetypes of advertising with vanishingly fine contours on the cream of his panels, adding a finicky modeling of hot pink and metal-gray washes. Also, with a shorthand use of collage: where the face of the sales goddess might appear in each, there is pasted here merely a pair of luscious lips, there a holographic winking eye.

These works of Hamilton’s, so fastidiously constructed and so devoutly attentive to the psychology of Madison Avenue, convey an almost adolescent fascination with American culture at its zenith of self-assurance. “Perfect weather for a streamlined world…. What a glorious time to be free” sang Donald Fagen in a 1980s hit wryly recalling the early days of the space age, and Hamilton’s set of panels—which include a 1962 collage of Kennedy gazing skyward from within an astronaut’s helmet—witness that now remote boom time. America’s engineering is truly sublime, the pictures proclaim, whether it dreams up the headlamp hoods of a 1957 Plymouth or the conical cups of an “Exquisite Form” brassiere: What else can you do but worship such marvels of modern imagination?

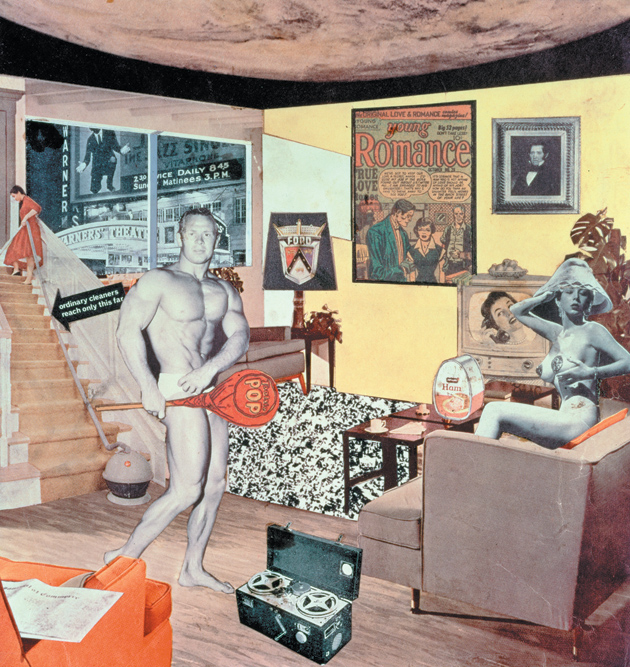

Yet “dreams” remains the operative word. Streamlining is a slave—or a master—to consumer desire, rather than to functionality, and creatures of desire such as the faceless sex symbol threaten to slide into nightmare. The pictures are not exactly satirical: nor does Hamilton hint in them that there could be any waking alternative to the reveries of capitalism. But their spare whiteness is almost as claustrophobic as the interior clutter in the most reproduced of all the artist’s images—a little ten-inch collage from 1956, entitled Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?, that presents a muscly hunk and busty bombshell trapped in a gilded cage of gadgetry.

What angle, then, were these visions of Americana seen from? As of 1962, the forty-year-old Hamilton had never as yet crossed the Atlantic. One might suppose that this son of a London truck driver was simply looking west for cultural excitement in the way that most of urban working- and lower-middle-class Britain has done ever since the advent of Hollywood. One well-known consequence of that trade pattern was that myths about the music of Memphis and Chicago, mutating in the backrooms of British pubs, ricocheted spectacularly on the United States during the Beatles-led pop “invasion” of 1964. Arguably, affairs in the art world worked in a comparable fashion: seven years before that, it was Hamilton in London who first started talking of “Pop Art”—a tag that would only be picked up in Manhattan when Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein made their public arrival in 1962. With his own versions of the images of Marilyn Monroe and Mick Jagger, with his artwork for the Beatles’ White Album, and with his denim jacket and John Lennon cap, Hamilton remained, alongside David Hockney and Peter Blake, Britain’s best-known face of the movement for the rest of that decade.

Advertisement

In its original sense, however, the “Pop Art” coinage had more to do with the campus than with the street. Hamilton had entered the art world as a teenage drawing prodigy: during his twenties, he had made his way working as an engineering draftsman; by 1957, he was teaching in an art school and talking his way around London’s various clusters of modernist architects and critics. During the previous four years he and several of these colleagues had put on ambitious multimedia exhibitions organized around abstract themes—biological form; mechanical motion; images in relation to perception.

Work on the last led Hamilton to think about the ways that the media and mass audiences operated in the postwar world. What might it be like, he put it to his highbrow associates, if activity in their own world—art school art—were likewise to reach out to those masses? Such a “Pop Art” might, he said, be “Transient… Young… Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky, Glamorous, Big business.” The proposal nonplussed his interlocutors. “It went down like a stone,” he later remarked. Yet it would emerge as his most prophetic move. For of course Hamilton’s wish list signaled where so much art, from Warhol down to Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, would head for the rest of the century, soon leaving all coherent definitions of modernism behind.

There is a parallel way to track how art moved on from that juncture: to see it as following, belatedly, the signpost erected by Duchamp back in 1917, when he bypassed traditional notions of skill with his readymade, his art of the “new thought.” Hamilton discovered Duchamp in the late 1940s, a point at which the Frenchman was still something of a secret. Drawn to his arch and intricate intellectual schemes—to his imperious facetiousness, one might say—Hamilton became his most ardent acolyte: he would translate his writings and would be authorized, before Duchamp’s death in 1968, to reconstruct the Large Glass2 for London’s Tate.

And yet his own response to Duchamp, as one artist to another, has set him in a singular, even contrary historical position, sideways to the currents of conceptualism and outsourced fabrication. Hamilton reasoned that since his icon had himself been an iconoclast, the truest way to respect him must be in some sense to reject him. Duchamp had persistently disparaged the optical (or what he called the “retinal”) pleasures of painting: that being so, Hamilton would honor them. Duchamp jumped art onto a new set of tracks, away from the well-worn mainline of studio skills: for his own part, Hamilton would—returning irony on the ironist—switch the points back again.

Hamilton’s reasoning was tailored to his temperament. What has most identified his output, from the exquisite illustrations to Ulysses he drew in 1949—Joyce being another of his father figures—to Unorthodox Rendition, an image of the imprisoned Israeli whistleblower Mordechai Vanunu painted within the past year, has been an assiduous fine craftsmanship. Much of his studio time over the intervening six decades has been given over to printmaking, translating a relatively small stock of chosen images into a plethora of variously tweaked impressions. Mannerly and cautious in his handiwork, Hamilton has been, if anything, the artist of the steadymade.

Meanwhile his choice of images, largely derived from photographs, has been stimulated by an argument with the abstraction that was dominant in his youth. Modernists in those days loved to talk about “the picture plane,” the surface whose flatness the painter ought frankly to assert. Hamilton countered their doctrine by insisting that “perspective is the dominant clue in our interpretation of any image.” By one means or another, his work has continued to tease away at those opposing propositions. Sometimes he taunts viewers with the suggested recessions of some chic interior or panoramic view, then denies access to that space by studding the picture surface with stout clots of paint or affixed bas-relief. In those turn-of-the-1960s panels, feminine curves took on an almost metaphysical import: What is a mere line, that it should weigh so on the male consumer’s mind?

“Pop Art,” then, was a transient label for the artist’s larger program—to revisit the various genres opened up by the old masters, from landscape to the nude, but with post-Duchampian hindsight and drawing on the “great visual matrix that now surrounds us” in the age of mass communication. Hamilton’s articulation of that agenda has the lofty authorial swagger that often surfaces in his texts. It comes through, for instance, when he writes of a large, foreboding interior painted during his sixties: “I have been moved to say that Lobby is an old man’s picture…. It is a metaphor for purgatory, the limbo in which we await transit to another condition.” Here, then, is a painter with his own poetic passions; one, moreover, rich in technical expertise, able to design a hi-fi system as well as to keep step with each new generation of computers; a reconfigured portraitist, still-lifer, and so on; in many ways, one might say, a model of the rounded artist and, at eighty-eight, an exemplar to his juniors.

Advertisement

One might also note that if Hamilton had never existed, art historians would have found it necessary to invent him. My awareness of the themes uniting his diverse oeuvre has been much enhanced by the new October Files volume Richard Hamilton, edited by Hal Foster. As well as an interview with the artist and various texts by him, the book includes essays of formidable erudition by Stephen Bann, David Mellor, and Sarat Maharaj. Delighted to converge on a contemporary who shares their own iconographical canniness (how satisfying to discover that the hunk and bombshell in that little 1956 collage are supposed, typologically, to stand for Adam and Eve!), these professors laud his ingenuity in ornate cadenzas. Mellor, for instance, on Hommage à Chrysler Corp.:

Thus the sightless, disembodied girl, her lips like a bicellular organism from [the biologist D’Arcy] Thompson, her breast a geometrically contoured target, the glamorous prop of the glamorous motor showroom, caresses the car-monster with, in the words of the contemporary Doris Day song, “A Woman’s Touch,” affirming and displaying this carnival mix of death and the maiden.

Or Maharaj, wrapping phrases from Duchamp around a panel from the same era:

The “fat, lubricious Bachelor- Machine,” well-oiled, heavy-breathing, throbbing, stands poised to perform in AAH! (1962) …[but] turns out to be little more than a flaccid penis, the inferno of passion the weak flicker of a cigarette lighter: the consumerist myth fizzles out as a “comically-dribbled sigh of ecstasy.”

For his part, Bann, noting how this sardonic drift in Hamilton sometimes turns scatological, arrives—rather wonderfully—at: “The turd still sounds the warning bell.” There is comedy, then, as well as learning to be had from this parade of rococo academese. And yet such touches are almost unavoidable: everything in Hamilton’s art rises up to elicit them, and each of these authors is simply responding with an on-cue exegesis.

Is that the agenda of the collection’s editor, Hal Foster, who in the same orotund spirit salutes the Chrysler picture by invoking “the fetishistic chiasmus of this tabulation”? Foster has long been a fixture of October, the bracingly theoretical New York art quarterly under whose aegis the book appears, a home for leftist suspicions of the art market and of the medium of painting in particular. Within that context, however, he has stood up for the value of a historically nuanced political awareness. And thus in Hamilton Foster finds something rare, a contemporary painter he can warm to. The artist, who once demurely explained that “my political inclination is to the left,” began increasingly from his middle age to devise images in sorrow and in anger. The high spirits with which he had embraced American design subsided, as he confronted events such as the Kent State shootings of 1970, the troubles in Northern Ireland, and the wars with Iraq in 1990 and 2003. The Vanunu painting is the most recent addition to a body of work that, in Foster’s view, reanimates another old fixture of the European tradition, the genre of “history painting.”

In the stimulating essay that concludes the volume, Foster considers what such an updated art of public life entails: “Hamilton is concerned to capture less the political event than its mediation—how it is produced for us precisely as an image—and it is this mediation that he both elaborates and exposes.” Pictures such as War Games (1991–1992), with its scanachrome print of a TV set displaying toy tanks in a sandpit model of the Gulf while blood leaks out from it onto the shelving beneath, open up the paradox of the private citizen’s “distant intimacy” with the contemporary “military-entertainment complex”—how we are at once immediately present, in there with the breaking news of bomb blasts and casualties, and also entirely, comfortably remote.

A recent exhibition of Hamilton’s politically oriented work at London’s Serpentine Gallery offered a chance to check these claims. It did indeed open up a paradox: for when one confronts these pictures firsthand, they remain almost exactly as distant as when one sees them in reproduction. They are devoid of visceral impact. The overall pattern of marks in each canvas or print is scrupulously deliberate; for instance, whatever was out of focus in a source photograph has been blurred with patient, sable-brushed care; but there is never a glimmer of expressive excitement. One is reminded that this onetime technical draftsman confesses to a distaste for the messiness of oil paint. Surely his primary allegiance remains to the thought-dominated art advocated by Duchamp. Surely his reengagement with the pleasures of “retinal” painting has been tentative, at most.

And yet art that could as well sit in another room as be present in this one is not necessarily for that reason ineffectual. As one moves away from it, the immediate inertia experienced before its listless surfaces might recompose as a metaphorical inertia, a register of the public affectlessness that concerns Hal Foster. Works of art come alive not just as facts but as intentions, and as a set of intentions, Hamilton’s oeuvre abounds in ambition, invention, wit, and fundamental political decency. I just feel that before academics fall in with its yearning to be paraphrased, they should take a longer view of the pantomime they’re being prompted to enact. They might note that this old enragé who dreams up a TV set leaking blood can hardly conform, at root, to any of their campus notions of philosophically informed irony. Why not take his own word for it? “In spite of their contrived sophistication my paintings are, for me, curiously ingenuous (like Marilyn Monroe).”

This Issue

August 19, 2010

The Crisis & the Euro