Radio receives little critical attention. Of the various methods for communicating ideas and emotions—books, newspapers, visual art, music, film, television, the Web—radio may be the least discussed, debated, understood. This is likely because it serves largely as a transmission device, a way to take other art forms (songs, sermons) and spread them out into the world. Its other uses can be fairly pedestrian too: ball games and repetitive, if remarkably effective, right-wing commercial talk radio. Rush Limbaugh is the radio ratings champ; according to the industry’s trade journal he reaches 14.25 million listeners in an average week. Sean Hannity, working the same turf, trails him slightly.

But an equally large audience turns to the part of the dial where public radio in its various forms can be found. Public radio claims at least 5 percent of the radio market. National Public Radio’s flagship news programs, Morning Edition and All Things Considered, featuring news and commentary alongside in-depth reports and stories that can stretch over twenty minutes—are the second- and third-most-popular radio programs in the country, each drawing about 13 million unique listeners in the course of the week. These NPR shows have far larger audiences than the news on cable television; indeed, all four television broadcast networks combined only draw twice as large an audience for their evening newscasts. Morning Edition and All Things Considered are supplemented by well-regarded programs like The World, a BBC coproduction with Boston’s WGBH, and the business broadcast Marketplace—programming produced outside of NPR itself but within the larger world of public radio. In polls, public radio is rated as the most trusted source of news in the nation. The audience for most of its programs dwarfs the number of subscribers to the The New York Times or The New Yorker, or the number of people who read even the biggest best sellers.

About one in ten Americans tune in to public radio each week; if you landed in a spaceship someplace in America searching for thoughtful and nonpartisan culture, your first stop would be the public radio stations that usually show up below 92 on the FM dial. You’d find not just the big news shows but also a variety of call-in shows: national ones, like On Point, The Diane Rehm Show, or Talk of the Nation, with its much-loved Science Friday edition, but also a number of superb local talk programs, with hosts like Leonard Lopate and Brian Lehrer in New York, Michael Krasny in San Francisco, Steve Scher in Seattle, Larry Mantle in L.A.—the list is very long.

These differ from the commercial right-wing shows in that they daily feature guests from a wide spectrum of American political and cultural life: on the morning I’m writing this, for instance, Tom Ashbrook of On Point in Boston spent an hour discussing the rise of social gaming on Facebook, Krasny covered “the troubled construction industry,” and The Leonard Lopate Show examined the current state of the company Google. The sine qua non of these efforts is Terry Gross’s relentlessly intelligent interview show Fresh Air, which is based in Philadelphia, has been running for thirty-five years, is syndicated to more than 450 stations, and claims nearly 4.5 million listeners.

And yet very little gets written about public radio. We have no equivalent of the late and lamented British magazine The Listener, which combined independent commentary with essays and features that had originally been broadcast as radio pieces; even NPR’s own (excellent) journalism forum, On the Media, usually concentrates on television or print. There’s no well-known radio equivalent of the Emmys or the Grammys or the Oscars (or even the Tonys). In a sense, I think, this reflects public radio’s smooth professionalism—it’s gotten so good at its basic task that it’s taken for granted, a kind of information utility.1

A Few of the Broadcasts Worth Listening To:

- This American Life

- Sound Opinions

- Planet Money

- Re:sound

- Too Much Information

- Radiolab

- Studio 360

- Fresh Air

- 360documentaries, with the best from the Australian Broadcasting Corporation

- Wiretap, from the CBC

- Transom podcast

- On the Media

- BBC Radio 4

- The Sound of Young America

- Q podcast

- Vocalo

- The Takeaway

- To the Best of Our Knowledge

I talked recently with Robert Krulwich, who first joined the NPR network just a few years after All Things Considered went on the air in the Nixon era and now cohosts the public radio program Radiolab, and he remembers those days as filled with invention:

Radio was dead—it was top 40. All the smarties were at the Times or The Washington Post, or if you didn’t want to be Woodward and Bernstein you went to work for Walter Cronkite at the Tiffany network. This group of nutty people wandered in and said, let’s do radio. We’ll reinvent it. Jump thirty-five or forty years ahead and where is Walter Cronkite? What happened to The Washington Post? And guess what, the nutty radio people have suddenly emerged as the focus for a huge audience. And now they have a little of the swagger of the Timesmen.

All that success has tended to wash out some of the distinctiveness. Another All Things Considered veteran, former senior editor Brooke Gladstone, who now cohosts On the Media, put it like this:

Advertisement

As they become the primary news source for more and more Americans, public radio newsmagazines are restricting their own ability to move listeners. Like physicians in medieval times they seek to balance the four humors (so as not be too choleric, sanguine, phlegmatic, or melancholy) by blood-letting. Public radio newsmagazines are looking a little pallid these days, because the passion has been drained off.2

In the rest of the public radio world, however, there’s invention underway at an unprecedented pace. Those who restrict their listening to Morning Edition and All Things Considered are well informed—there’s no better news operation in English-language broadcasting. But they are missing a quite different world, one that’s never been richer or, thanks to the Internet, easier to access.

The most important name in that other world is Ira Glass, the inventor of the show This American Life. He learned his craft at the big NPR news shows and slowly developed a powerful style that centered on storytelling. There was a group of others—like Davia Nelson and Nikki Silva (known as the Kitchen Sisters), David Isay, and Jay Allison—who had long been producing remarkable programs, including segments for the flagship news shows, extended features, ranging from quirky accounts of family kitchen rituals to politically minded portraits of juvenile prisoners. The best ones came to be called “driveway moments,” because listeners were so hooked that they would linger in their cars to hear the end of a piece even once they’d gotten home. In fact, NPR now packages CD collections of these beloved pieces.

But Glass figured out that he could make a weekly hour entirely of this kind of radio, dispensing with traditional news and talk; and since 1995, under the wing of Chicago station WBEZ, that’s what he’s done in This American Life. “During the early days, Ira would always say, ‘I just put a piece on our show that was rejected by All Things Considered.’ He was really proud of that,” recalls Torey Malatia, president of WBEZ. The pieces were often long—sometimes one would fill an entire hour. And they sounded odd: Glass himself doesn’t exactly have a Bob Edwards radio voice, but some of the people who joined his ensemble (the wonderful Sarah Vowell, Joe Richman, Scott Carrier, and others) wouldn’t even have gotten an interview at the smallest commercial radio station. What they shared, besides wit and intelligence, was a commitment to covering the 330 degrees of life that didn’t show up on the newscasts. It’s about life the way most of us experience it, where heartbreak or lunch is as important as stock prices or distant revolutions.

In Robert Krulwich’s account, “Ira comes along and says, ‘Why don’t I cover things that don’t involve governors?'” In its first year This American Life did shows on themes like “Simulated Worlds,” which included a nineteen-minute segment where Glass took the University of Chicago medievalist Michael Camille to dinner at a restaurant in a fake castle called Medieval Times, where you ate with your hands and watched jousting contests. (Camille concludes, with the generous spirit that usually marks the show, that “despite inaccuracies the restaurant captures something essential and interesting about the Middle Ages.”) Right from the start, word spread quickly, especially since the launch of the program more or less coincided with the ability of the Internet to spread audio files, albeit slowly and clunkily at first. The program shows no sign of weariness fifteen years later. This past season has a classic hour-long report on the life of a rest stop along the New York State Thruway and an account of a Chinese man who spends every weekend talking suicides off a high bridge near Nanjing. “It turned a lot of people my age and younger on to radio,” I was told by a prominent young producer. “Now young people come to the radio with the idea that it’s cool. ‘Cool’ and ‘radio’ in the same sentence is a whole new phenomenon.”

Glass himself is more modest, but he does note that a generation has grown up listening to the show, which means that when new interns arrive it no longer takes a year to train them. “Now they get it right away,” Glass told me. “They understand it’s unlike the old public radio reporting where characters weren’t characters. They get that we need arc, emotions. That’s now not a crazy thing.”

The years since have seen a cascade of new work emerging, some of it confined to a single radio station but all of it available quite easily via podcast. You can hear much of the best on shows like Studio 360 (which covers culture from Iranian rock and roll to novelist Gary Shteyngart to a convention of black banjo players in rural North Carolina) or Hearing Voices (tour a mosque, visit the Crow Reservation), or in NPR features like Radio Diaries, or in documentaries from Homelands Productions about the daily grind of work for people ranging from a thirteen-year-old Bangladeshi in a shipbreaking yard to a low-end Bulgarian nightclub singer.

Advertisement

It’s not all about or by newly minted hipster urbanites. Wisconsin Public Radio has for many years produced and syndicated the low-key and in-depth To the Best of Our Knowledge, and from Alaska comes the remarkable Encounters, which is mostly just nature writer Richard Nelson out in the Alaskan wild with a microphone. Radio Open Source features the passionate radio veteran Christopher Lydon in conversation with a variety of contemporary intellectuals, among them David Bromwich, Nicholas Carr, and the psychologist Paul Bloom.3 “There’s a small world of heartfelt passionate people trying to do big work,” says Julie Shapiro, who runs the Third Coast International Audio Festival, a yearly gathering of the audio tribe in Chicago. Her Third Coast colleague Gwen Macsai hosts Re:sound, an ear-opening weekly show of the best material from around the English-speaking world: a recent show on “water,” for instance, featured the story of an Adriatic ocean liner turned into a Toronto restaurant and an “audio composition featuring bell buoys recorded while kayaking in Portland Harbor.” You can listen to people starting out at Transom.org, a website designed to teach newcomers and showcase their work, and if your local radio station doesn’t air much of this material, you can assemble your own listening schedule quite easily at PRX.org, the Public Radio Exchange, which serves as a middleman for independent producers and local stations. The sheer abundance of programming will stun you—dozens of new shows are uploaded every day, most of them owing at least a little to the aesthetic unleashed by This American Life.

If there’s a next Ira Glass, it might well be Jad Abumrad, who has teamed with the veteran reporter Robert Krulwich to produce what may be the most- talked-about show of the moment, Radiolab. In an almost comic attempt to make their job hard, the duo take only the most difficult subjects from science and philosophy: “Time,” “Morality,” “Memory and Forgetting,” “Limits.” They’ll usually interview a few experts, but the beauty of the show is the interplay between the hosts, separated by several decades and by sensibility. A musician by background, Abumrad plays with the sound of voices to underscore points, to circle back, to undercut assumptions. “Jad uses a layered, jazzlike metric,” says Krulwich, “creating breadths and spaces and layers of sound that are new. Not new to Tchaikovsky or John Cage, but new to radio.”

Meticulously engineered, the soundtrack often repeats, stutters, returns. The recent show on “Numbers,” for instance, begins with Johnny Cash’s famous song about the last twenty-five minutes of a condemned man’s life and proceeds to an interview of sorts with a thirty-six-day-old baby and a Parisian neuroscientist who has demonstrated the early age at which children acquire numeracy. You can hear how infant brainwaves respond to a picture of eight ducks—and what happens when sixteen suddenly appear. “I remember when the show began, I’d get this comment all the time: ‘I really can’t wash the dishes when I listen to you guys,'” says Abumrad.

Meaning, there’s an expectation that when the radio is on you’re only using a quarter of your brain. But now that we’ve got podcasting, people will put it on iPods or whatever. People will listen to it many times, will appreciate the layers and the details. Before it was hard for us to justify the amount of labor we put into it. Because it was disposable, just out there in the world and then gone.

Tough as the show’s topics are, and demanding as the sound can be, it’s also remarkably intimate because of the interplay between Krulwich and Abumrad. “We knew we could make the material interesting to each other, and that if we did it in duet form and showed our affection to each other, it would be kind of a warm place,” says Krulwich. “That’s intentional, because the subjects are kind of cool. So we thought the mood should be warm and seductive. We’re not afraid to say ‘this is hard and we don’t get it either.'” Despite or because of the difficulty, the show clearly works. It’s already on about a third of NPR stations, and more than a million people a month download the podcast.

So in one sense this is the perfect moment to be a young radiohead. It’s like 1960s and 1970s cinema, with auteurs rewriting the rules. New technology lets you make radio programs cheaply: Pro Tools sound-editing software has now replaced much of the equipment used in big, expensive studios. Listening is even cheaper: the iTunes store has thousands of podcasts, including all the ones described here, available for free download in a matter of seconds. “It’s a transformative and exciting moment, a huge revolution,” says Sue Schardt, executive director of the Association of Independents in Radio.

But there’s one problem, and that’s the economics of this new world. Radio is now cheap to make, true, but the people who make it still need to live. And it’s very hard to get paid anything at all; in the early weeks of the fiscal downturn two years ago, NPR canceled two of the shows—Weekend America and Day to Day—that were consistently airing the work of new independent producers. Up-and-coming broadcasters are increasingly left to make their own way. Consider, say, Benjamen Walker, whose show Too Much Information airs weekly on New York’s independent radio station WFMU. It absolutely crackles—an hour-long mix of “interviews with real people, stories about fake people, monologue, radio drama.” It’s good enough that 240,000 people have downloaded some of the twenty episodes he’s made so far. That’s a lot of people, but it’s zero money, since podcasts, like most websites, are by custom given away for free. Walker’s previous show, a similar effort called Theory of Everything, was widely promoted on the Public Radio Exchange, and six public radio stations across the country actually paid for and ran it. “I think I made $80,” he says. “If I thought about it too hard, I would just quit. It’s much better not to think about it.”

Even with a big radio station behind you, the going can be slow. WBEZ in Chicago, home to This American Life, also produces a show called Sound Opinions, which has been airing weekly for more than a decade. It’s a show about popular music, in the vein of Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert’s At the Movies, but much better. The hosts, Greg Kot and Jim DeRogatis, are the longtime music critics at the Chicago Tribune and Sun-Times (though DeRogatis has just left the Sun-Times for a job at a Chicago website), and they began the program on a commercial station in Chicago.

The first time you hear it you think: Why haven’t there always been programs like this on the radio? Intelligent and funny discussion about music, interviews with articulate musicians who play on the air, long and careful dissections of classic albums. A show will begin with five minutes about the greater significance of current teenybop sensation Justin Bieber and proceed to a half-hour analysis of London Calling, the great Clash album that helped mark the punk era of the early 1980s. “When people hear it, what they hear is two excitable guys who are almost nerds about their music and aren’t afraid to let it show,” says Kot. Much of the pleasure is the interplay between the hosts, Kot understated and DeRogatis over the top—there’s an element of dorm room conversation carried on at the very highest level. And every week, for almost every listener, there’s the pleasure of discovering new sounds you didn’t know were out there. Their annual trip to Austin for the South by Southwest music festival shows you just what cultural reporting should really sound like, full of bias and brio and the joy of discovery. The show’s audience is almost as fanatic as Glass’s—its weekly podcast is one of iTunes’ most popular downloads.

And yet making it work economically has been a struggle. Its budget, which covers everything from a pair of producers to track down audio clips to the engineering required for regular live performances, is only $350,000 a year (for a weekly hour, with two hosts: you couldn’t do a single episode of network TV at that price), but Torey Malatia hasn’t yet been able to convince enough stations around the country to carry it to break even. “Stations get charged by their size. The very biggest would pay $4,000 a year to run it every week,” he says. “But we normally cut the price down. We usually let them run it for a year for free, just to get it before audiences. Once it’s on the air, program directors begin to understand how audiences are connecting.”

Malatia’s accounting underlines what may be the biggest problem for innovation on the radio—the role of program directors at all the public radio stations around the country. They are the gatekeepers for what gets on the air—and their default mode is clearly to say no. “I’m not a radio veteran,” says Kot, “but in my experience, program directors are conservative, afraid to rock the boat.” They depend on their listeners to ante up about half a station’s budget at pledge time, and local underwriters such as restaurants and bookstores to provide most of the rest, so they don’t want to do anything that might offend them.

But the result is all too often flaccid radio, and listeners who have no idea what else is out there that they might enjoy. There are public radio stations so hidebound that they run the not-that-hilarious Car Talk twice each week. It’s a waste of the precious hours in the broadcast day to repeat the program, and it’s not a good sign for the future that program directors aren’t taking more chances. If they’re not careful, NPR could wind up without a farm team of experienced new program makers, and with the same demographic problem now crippling public television (to see what I mean, check out your public TV pledge drive and try to imagine what age group they’re appealing to with overweight doo-wop groups squeezing into sequined suits). Sound Opinions is as good a barometer as any; if your local public radio station isn’t airing it, they’re not trying very hard.

Other countries solve this problem with one centralized, publicly financed, more or less independent service like, say, BBC’s Radio 4 or the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Radio National, where headquarters in London and Sydney simply lay down the law about what their local affiliates will carry. New programs appear regularly and for limited runs. It’s worth listening in on the Internet to get a sense of how literate and engaged the programming is, almost every hour.

But that outcome seems unlikely in a system as decentralized as ours. A better agent of change would be more program directors like Malatia, who takes real chances despite the fact that at WBEZ he has a huge station to care for. “You don’t want to experiment to the point where you put the entire thing in jeopardy,” he says. “But you can budget for a certain amount of risk, and to recover from that risk. The audience is forgiving of that, I think—maybe even admires it.”

You can, Malatia suggests, train an audience to be a little more daring, just as you can train them to be staid. “He’s never lost his enthusiasm for constantly pushing forward,” says Kot. “I think he wants to put in radio shows that a person like him would be proud to listen to. And he thinks everyone is like him.” He is, in other words, like a great film producer, book publisher, or magazine editor, and the country’s culture is richer for having him. But willingness to push the envelope, to try things that could fail—that, from the experience many recounted to me, doesn’t seem impossibly hard. Any station manager could do at least a little of it, and if they did then the prospects for new radio would be much better.

It seems churlish to criticize even mildly the flagship public radio news shows—their reliable excellence deserves lavish praise. In recent years, though, it’s started becoming clearer that, for all their polish, the big shows like All Things Considered suffer from some of the same constraints that plague other parts of elite American journalism. They aim for a careful political balance—one academic study found their list of guests slightly to the right of The Washington Post and “approximately equal to those of Time, Newsweek, and US News and World Report.” That’s not a particularly interesting place to be, and it may explain why, especially in the Bush years, many left-of-center listeners defected to Amy Goodman’s Democracy Now!, a highly professional but ideologically engaged daily hour on the Pacifica network.Others—particularly young listeners—are listening to The Takeaway, a morning news show that pairs veteran public radio voice John Hockenberry with Celeste Headlee. It takes stories one after another, and gives each a few serious but fast-paced minutes. It feels electric, alive—Web-paced journalism, purposely not as polished as Morning Edition but every bit as intelligent. “There ought to be something in the public radio idiom that delivers information live,” says Hockenberry.

The most stinging critique of the big NPR shows, of course, is the same one that you could make of our other national media. For the most part All Things Considered, just like the Times or CNN, managed to miss the biggest stories of the last decade: the errors of going to war in Iraq and the endlessly inflating economic bubble that eventually laid us low. In fact, the first account of that bubble and one of the best came from This American Life, which has the financial resources (it’s carried on virtually every public radio station, and at decent rates) to let Glass put a reporter on a story for three or four months, something unheard of anymore outside the Times, The New Yorker, Rolling Stone, and a very few other outlets. Two reporters, in fact: Adam Davidson and Alex Blumberg, who in May 2008 (i.e., months before Lehman Brothers crashed) produced a truly startling account called “The Giant Pool of Money.”

It tried to answer the question that everyone else should have been asking: “Why are they lending money to people who can’t afford to pay it back?” Davidson and Blumberg tracked down Nevada mortgage brokers and Wall Street technicians and many other people who could actually provide some clues. “It’s just brute force reporting, going through so many guys till you meet someone who will be honest with you,” Glass told me. The show won the Peabody, Polk, and duPont-Columbia awards, and it awed almost everyone who heard it (like everything else I’m describing, if you own a computer you can listen to it today, free of charge and without the slightest hassle). They’ve done several such shows on the economy since, and more importantly spun off a podcast called Planet Money that manages to make economics, and our current ongoing financial anemia, sound clever and comprehensible.

This American Life has given the same treatment in the months since to the health care debate and the failure to deal with Haiti. It’s as if, like the Radiolab guys, Glass is choosing the very hardest topics, the ones that make you want to switch off the radio. But you don’t, because you know how compulsively listenable it will be. “Broadcast journalism could be remade with a different aesthetics,” Glass told me. “It’s kind of antique. If someone would do a daily news show with the cheerful casualness and with the seriousness the Planet Money guys bring to it—that’s a thing that’s waiting to be made.” Indeed.

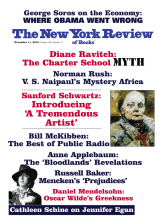

This Issue

November 11, 2010

-

1

Taken for granted, but not always understood. Though listeners often refer to their “NPR station,” in fact public radio licenses are usually held by a college. The individual stations buy programming from a variety of sources, including National Public Radio, Public Radio International, and other smaller consortiums. Most of the funding for public radio comes from individual listeners and local business underwriters; 10 percent comes from the federal government, through the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, a percentage that has declined sharply over the last four decades. ↩

-

2

Quoted in an essay in a new book from Duke’s Center for Documentary Studies: Reality Radio: Telling True Stories in Sound, edited by John Biewen and Alexa Dilworth (University of North Carolina Press, 2010). ↩

-

3

I should note that as the author of thirteen books I’ve appeared on many of the shows described here; that indeed they’ve been the intellectual oases amid the desert that is a book tour. ↩