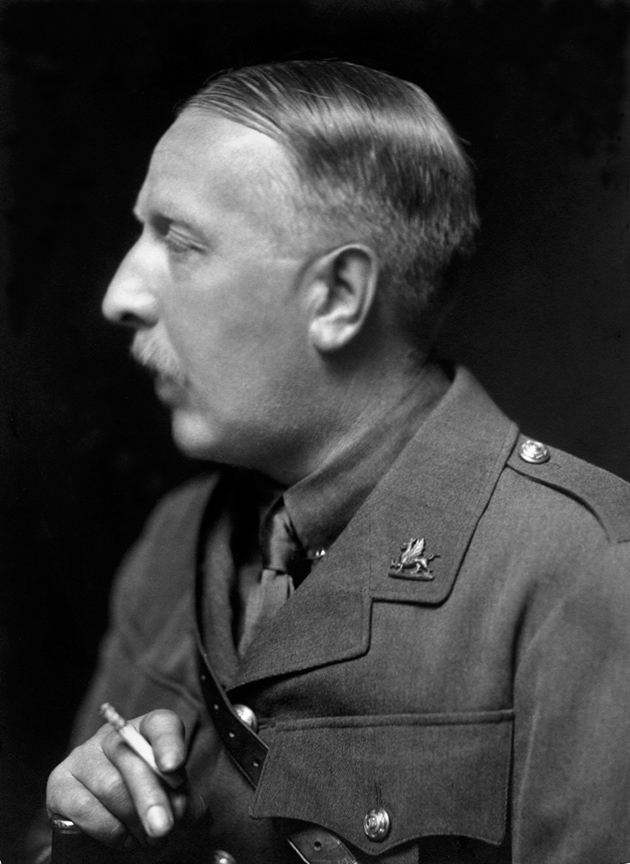

Ford Madox Ford was a man full of contradictions. His name sounded thoroughly English and he considered himself to be the last Tory; during World War I he said that he never felt so calm as when he wore the King’s uniform. In fact, however, his father was a German émigré, Francis Hueffer, and Ford himself was known as Ford Madox Hueffer until he changed his name to Ford Madox Ford by deed poll on June 4, 1919, as a way of downplaying his German origins. He was obsessed with ideas of what gentlemen do and do not do and he sometimes claimed that he was descended from German barons, but in fact his Münster family members were (and still are) publishers and printers.

He was an inveterate liar—or rather what the French call a mythomane, which suggests someone who exaggerates for the love of the legend and not for any direct personal gain. Or perhaps he “lied” only because he wrote so fast that he couldn’t recall what he’d already said about someone or an event. His politics were confusing. He wrote of “the true Toryism which is Socialism,” he opposed liberal democracy because it promoted plutocracy, and he had a sentimental, literary attachment to feudalism.

In many ways he can be seen artistically as the last and greatest heir to Henry James, who was a friend. Like James he often dictated all or part of his novels. He loved to play with point of view and the underlying motives of his narrator. His plots, like those of James, can sound melodramatic when summarized but in the actual telling they become so gauzy with subtlety that at moments the reader isn’t sure what exactly is going on. His characters, like James’s, are obsessed with jousting for position and often use sexual allure to gain the advantage, but they are just as likely to throw over everything out of excessive idealism.

The international theme, which fascinated James for the first half of his career, was also of great interest to Ford. After all, the narrator of Ford’s best novel, The Good Soldier, is an American who uses his American origins as an explanation of his not-quite-believable naiveté as he interacts with the wily English. There is a lot of dialogue in the fiction of both James and Ford and sometimes there are tense dramatic exchanges, full of sudden reversals, that sound scripted for the theater. One of Ford’s deepest regrets was that neither Conrad nor James, the two writers he most admired, had much respect for his work.

But if Ford is at the end of one tradition, the Jamesian, he is also at the beginning of another. As a poet he was an “imagist,” which meant that he often relied on free verse and direct sensory impressions presented in brief bursts, haiku-like, without interpretation. In prose he said he was an “impressionist,” which meant several things to Ford, though he and Joseph Conrad, who worked out their ideas together, believed that fiction is primarily a visual art and that the writer should be more concerned with the vividness of his remembered or invented images than with facts. Ford wrote:

Impressionism exists to render those queer effects of real life that are like so many views seen through bright glass—through glass so bright that whilst you perceive through it a landscape or a backyard, you are aware that, on its surface, it reflects a face of a person behind you.

For Ford experience was rarely ordered or hierarchical. It was all a jumble and the function of literature was to reproduce that confusion, though in a fashion that was clear and intentional, never random. Simultaneity was one of his artistic strategies, which is most clearly seen in Parade’s End.

Ford could be airily dismissive of factual accuracy, which he considered “pedantic,” but he remained scrupulously faithful to recording his exact sense memories. His inaccuracies got him into trouble with the literal-minded, especially since he wrote several different versions of the same events in his various memoirs. As he said in the introduction to his first volume of reminiscences, Ancient Lights: “This book, in short, is full of inaccuracies as to facts, but its accuracy as to impressions is absolute.” Further on he adds: “I don’t really deal in facts, I have for facts a most profound contempt.”

He wrote easily, sometimes fatally so, and he turned out more than eighty books, including a mammoth March of Literature late in life. He wrote book-length studies of Henry James, Conrad (with whom he coauthored three novels), Rossetti, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, his grandfather the painter Ford Madox Brown, and Hans Holbein, two books about New York, literary reminiscences (including It Was the Nightingale, about Paris in the 1920s), a suffragette pamphlet in 1915 (Monstrous Regiment of Women), books about Provence, books about London, books about the English character, two World War I (fairly mild) propaganda attacks on the German character, collections of poetry, literary critical essays, anthologies he edited—and of course his great and not-so-great novels.

Advertisement

Ford thought of himself as an experimentalist, and as an editor he championed the avant-garde, though he always feared he was older than most of his modernist friends and was being outstripped by them. In the 1920s in Paris he founded the transatlantic review, which published Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, E.E. Cummings, Jean Rhys (his lover for a while), E rnest Hemingway (who worked as his assistant editor), Gertrude Stein, Basil Bunting, and many others—so many Americans that he later claimed that more than 50 percent of his contributors were from the Midwest or West (including Pound, Stein, Eliot, and Hemingway). He published James Joyce, who, Ford said, made “little jokes, told simple stories and talked about his work very enlighteningly.” Throughout his career Ford was so generous to other writers that Pound remarked that when someone else wrote a good book in London there was only one person, Ford, who was genuinely happy about it, “one man with a passion for good writing.”

Early on in Pound’s career, before World War I, Ford had played a decisive part. Ford was living in a village in Germany and Pound came to visit with his first real book of poems, Canzoni. Pound was twenty-five and arrived in Giessen wearing a green shirt with glass buttons. Ford was thirty-eight. The older man couldn’t bear the artificiality and pretentiousness of Pound’s poetic diction. As Hugh Kenner puts it in The Pound Era:

The summer was the hottest since 1453. And into these quarters marched jocund Ezra Pound, tendering his new book that chaunted of “sprays [to rhyme with ‘praise’ and ‘rays’] of eglantine above clear waters,” and employed such diction as “hight the microcline.” Ford saw that it would not do. The Incense, the Angels, elicited an ultimate kinesthetic demonstration. By way of emphasizing their hopelessness he threw headlong his considerable frame and rolled on the floor. “That roll,” Pound would one day assert, “saved me three years.”

Ford fervently believed—and persuaded Pound—that a writer should write “nothing, nothing, that you couldn’t in some circumstance, in the stress of some emotion, actually say.” Indeed Ford’s prose, more than that of any other writer of his period, sounds spoken. As he said in 1938 about his much earlier collaboration with Conrad, he tried to evolve for himself “a vernacular of an extreme quietness that would suggest someone of some refinement talking in a low voice near the ear of someone else he liked a good deal.” This could just as easily be a Jamesian precept and in our own day Colm Tóibín (especially in The Master and Brooklyn) seems to be subscribing to this hypnotic practice.

Ford was born in 1873 in Merton, Surrey, now part of London. His German-born but fiercely pro-British father, the music critic for the Times, died when Ford was just fifteen years old. The boy went to live with his maternal grandfather, the Pre-Raphaelite painter Ford Madox Brown. When he was eighteen he published his first book, The Brown Owl, a fairy tale for children; when the very shy Ford was introduced to Thomas Hardy, the great, much older writer thought it must be a nature book, questioned the musicality of the title, and reduced Ford to stammering silence.

The next year Ford converted to Catholicism to please his German relatives, though he seems to have been interested in the church more as a force for order than as an invitation to religious ardor. By 1898 Ford was married to Elsie Martindale, a childhood sweetheart, and was collaborating with Joseph Conrad, with whom he co-authored three novels, The Inheritors, Romance, and The Nature of a Crime. In letters to friends Conrad could be catty about the much younger Ford, but Conrad—who was always broke, often blocked, and terrified of missing serialization deadlines—needed the ever fluent Ford. Not many novelists before Conrad and Ford had collaborated (one thinks of the Goncourt Brothers and Dickens and Wilkie Collins, but few other pairs of literary authors come to mind), and indeed their work together produced nothing memorable beyond their theorizing about the novel, though each of them did extraordinary independent work during their years of collaboration.

Conrad wrote, among other things, Nostromo and Ford wrote a trilogy of historical novels about Henry VIII and Katherine Howard, The Fifth Queen, Privy Seal, and The Fifth Queen Crowned. Conrad praised him for leading the historical novel to its apotheosis, but the trilogy suffers from the usual Monty Python–sounding “period” dialogue: “Ignoble, ignoble, to twit a man with that Eton villainy,” or “Oh moody and suspicious artificer. Afflavit deus! The wind hath blown dead against Calais shore this ten days.” Nevertheless the trilogy is often counted as one of Ford’s (few) enduring works.

Advertisement

Although Ford was physically awkward and wheezed and was obese and looked like a seal with his limp blond hair and mustache and liquid eyes, he was a successful womanizer and moved from Elsie to her sister to Violet Hunt, an ex-lover of H.G. Wells, and on to half a dozen other women, and each time he was convinced he was in love. Elsie, his first and only wife, refused to divorce him; if she had done so Ford would surely have married at least two of his subsequent loves. For the most part his women were writers, often of note. He was usually nearly penniless and living on the cheap in falling-down cottages in the English countryside, and once he even declared bankruptcy. The Good Soldier went into a second printing but earned only £67. Nevertheless he traveled extensively, to America and to his beloved Provence in particular, and appeared to be cheerfully bohemian in his values.

In 1915 he wrote The Good Soldier. Although in the same year he published two books of war propaganda, The Good Soldier, despite its title, is distinctly about the privileged pre-war world of rootless invalids, real or imaginary, visiting Continental spas and entering into dangerous amorous intrigues. A case can be made that Ford was dramatizing in this novel if not the events at least the tensions underlying his own messy love life. The plot undergoes so many surprising reversals that halfway through the reader can’t imagine what possibly could come next—and is he or she surprised!

Ford had a very difficult war. He was forty-one when he volunteered in July 1915 and not in good shape. He was under fire for ten days during the Battle of the Somme and was so traumatized that he lost his memory for a long period—an infirmity he ascribes to his principal character, Christopher Tietjens, in his tetralogy about the war, Parade’s End, written in the 1920s. Even during the war Ford was very cynical about how it would be perceived afterward. As he said to Wyndham Lewis:

One month after it’s ended, it will be forgotten. Everybody will want to forget it—it will be bad form to mention it. Within a year disbanded “heroes” will be selling matches in the gutter.

When Ford recovered he moved to France, alternating between Provence and Paris, where he edited the transatlantic review. Curiously enough Ford ended his long and restless life as writer- and critic-in-residence at the tiny Olivet College in Michigan, where he organized the first writers’ conferences ever held anywhere. He must have liked the admiration of undergrads, since as Stella Bowen, one of his mistresses, said, he needed “more reassurance than anyone I have ever met. That was one reason why it was so necessary for him to surround himself with disciples.” He had intense friendships with older and younger men, all of a literary sort. He died in 1939 (at Deauville in France) and was thus spared the second great war.

Although Ford wrote some excellent, rather prosy poetry, his heart was given over to fiction. Even in praising Pound’s great Cathay poems, Ford wrote words that only a novelist could have penned: “Beauty…is the most valuable thing in life; but the power to express emotion so that it shall communicate itself intact and exactly is almost more valuable.”

Max Saunders, Ford’s splendid biographer (Ford Madox Ford: A Dual Life in two volumes), is one of the editors of a new four-volume edition of Parade’s End. The first (rather expensive) volume, Some Do Not…has now appeared. It comes with Saunders’s very useful introduction and copious notes giving variants as well as explanations of now obscure references. Saunders has also reconstructed Ford’s dramatic original ending. The second volume has also appeared, edited by Joseph Wiesenfarth. The final two volumes will be edited by two other editors.

Published in four parts between 1924 and 1928, Parade’s End leads its bumbling Tory of a hero, Christopher Tietjens, into the war—and presents a parallel struggle between him and his beautiful, rich, aristocratic bitch of a wife, Sylvia. She may well be one of the most monstrous women in fiction. She tries to subvert Christopher at every point, even on the battlefield with his commanding officer. When an American woman cuts down the centuries-old tree on her husband’s estate, she condones it; Groby Great Tree has long symbolized the strength of rural England. She beats a pet dog to death. She cheats on Christopher constantly (his son and heir is another man’s child), yet she is fiercely jealous of Christopher’s (entirely pure and innocent) love for a penniless girl, Valentine Wannop, and does everything to ridicule and undermine it. Sylvia even tries, unsuccessfully, to convince Christopher’s brother Mark that Christopher is a cad and should have his allowance cut off.

There is nothing Sylvia will not do to humiliate her long-suffering, virtuous husband. Since he does not believe in divorce, he is powerless against her. In any event his ideas about what an English gentleman will and will not do prevent him from striking back. I suppose today we’d say she is a sadist and he a masochist, though such terms flatten out the complex moral subtlety of these characters. Sylvia has contempt and respect for her husband’s unassailable goodness in almost equal measure.

Rather than narrating long sweeps of history (as Flaubert does in Sentimental Education) through short scenes, one after another in chronological order, Ford sets up shop in a key moment and thoroughly explores it (somewhat as Edward St. Aubyn more recently does in his dark, fascinating trilogy, Some Hope). Then months or years go by and another crucial moment is presented in slow motion. In Some Do Not…, the first volume of Parade’s End, several years pass between Part I and Part II, for instance. The slowness of the storytelling gives Ford room for his famous impressionism. He has the space for giving Tietjens’s thoughts, for rendering bits and pieces of overheard dialogue, for describing the scene (a perfectly appointed Edwardian train compartment in the opening pages; later, a sumptuous English breakfast interrupted by the appearance of the mad host; still later, a ride through the countryside all night long through a pea-soup fog).

This fog-bound night is one of the most striking moments in the whole book and the one scene I remembered thirty years after an initial reading. Madly in love with Valentine and yet scientifically observant of the light effects produced by the silvery fog, Tietjens goes through a night at once ecstatic and calm. Although nearly medieval in his devotion to Valentine, Tietjens is also a lightning calculator and a repository of so much knowledge, trivial and grand, that he spends his off hours mentally correcting the Encyclopedia Britannica.

One of Ford’s best friends, Arthur Marwood, had this same breadth of knowledge. He was a descendant of a king and the first cousin of Lewis Carroll. Ford considered Marwood to be at once his double and his opposite, and as the embodiment of a type, “the heavy Yorkshire squire with his dark hair startlingly silver in places, his keen blue eyes, his florid complexion, his immense, expressive hands and his great shapelessness.” After Marwood died an early death from tuberculosis, Ford based many of his aristocratic characters on him, especially Tietjens. As Max Saunders summarizes, Marwood’s “traits can be glimpsed in characters from most of Ford’s novels after 1905.” These include, among others, Henry VIII in The Fifth Queen trilogy; Dudley Leicester in A Call; Mr. Luscombe in The Simple Life Limited; both the Duke of Kintyre and Lord Aldington in The New Humpty-Dumpty; Ashburnham in The Good Soldier; George Heimann in The Marsden Case; and Hugh Monckton in The Rash Act and Henry for Hugh. Of course Tietjens is the most extended portrait. In real life Ford even began to impersonate many of Marwood’s peculiarities. The whole of Parade’s End can be read as a homage to this larger-than-life quixotic figure and to Ford’s obsession with him.

In the last volume of the tetralogy, The Last Post, the entire action takes place in just two days. Tietjens’s brother Mark is dying and is nearly speechless, either from a stroke or from choice. The war is over and the family is living in reduced circumstances since Christopher Tietjens has decided not to draw on his family’s money. Mark is married to a Frenchwoman; Christopher is living “in sin” with his beloved Valentine and she is very pregnant, about to give birth to their child. He is earning a living selling old furniture; his partner is an American who refuses to pay Christopher his due. Groby, the family estate, has been rented out to an insufferable American woman who claims to be descended from Louis XIV’s mistress (and later wife), Madame de Maintenon.

Almost as in a Cubist painting our final notion of Tietjens is built up through different points of view. We are privy to Valentine’s thoughts and to Mark’s and to those of Mark’s wife and of Sylvia, who has had a change of heart and becomes a more benign presence. Valentine is afraid of losing her baby at the last moment or of having its life cursed by Sylvia’s presence (Valentine sees her as a huge, beautiful statue). The Americans come off very badly—grasping and dishonest and besotted with European titles and old things they’re not willing to pay for.

Mark is almost a caricature of the English gentleman—more rigid and considerably less intelligent than Christopher but just as decent. In an earlier volume Sylvia has started the rumor on the battlefield that Christopher wants to be Christlike—an idea that shocks and appalls his general. As Mark thinks:

That had seemed horrible to the general, but Mark did not see that it was horrible, per se…. He doubted, however, whether Christ would have refused to manage Groby had it been his job. Christ was a sort of an Englishman and Englishmen did not as a rule refuse to do their jobs….

A few pages later Mark is identified with the ultimate English gentleman’s credo:

Mark’s horror came from the fact that Christopher proposed to eschew comfort. An Englishman’s duty is to secure for himself for ever, reasonable clothing, a clean shirt a day, a couple of mutton chops grilled without condiments, two floury potatoes, an apple pie with a piece of Stilton and pulled bread, a pint of Club médoc, a clean room, in the winter a good fire in the grate, a comfortable armchair, a comfortable woman to see that all these were prepared for you, and to keep you warm in bed and to brush your bowler and fold your umbrella in the morning. When you had that secure for life you could do what you liked provided that what you did never endangered that security. What was to be said against that?

If Ford can enter into this absurdity so thoroughly it’s partly because he believes it or at least can appreciate it. He was an outsider and half German, just as for most of his life he was poor and living outside England and outside marriage with various artistic women. But at the same time he admired Marwood and emulated him, revered his German father’s notions of being an English gentleman, embraced Catholicism and his identity as a Tory. In this way he was like the half-Jewish Proust, who devoted huge amounts of energy to studying the French aristocracy and memorizing its eccentricities.

But Proust was not only an apostle of snobbism but also its most observant and fervent critic. Perhaps Proust’s disappointments in love and friendship made him lose his faith in the values he’d once embraced. Certainly the Dreyfus Affair thoroughly disillusioned him and his sexuality further alienated him, as did his bad health.

Ford was less hysterically and more genuinely sociable than Proust. He was a robust survivor. He was much more casual about controlling the quality of his oeuvre than Proust, though Ford took a justifiable pride in The Good Soldier and Parade’s End. Since, unlike Proust, Ford does not have a narrator who hovers over the entire book, there is much less attempt at “wisdom” in Parade’s End, and all the thoughts and aperçus can be ascribed to particular characters in unique dramatic moments. Proust contrasted family love (the only genuine form of love) with the illusions of romance; nothing comparably bleak appears in Ford. Proust saw in the Great War the collapse of all social values; Ford did not go so far. Tietjens is an emblem of all that was great about the old pre-war England and at no point does Ford suggest that he must be downgraded in the reader’s esteem. Because Ford was a complex and divided personality, his look at the English character is always shaded, if never disillusioned.

If Parade’s End is due for a revival it’s not for its large historical or philosophical truths but because it is panoramic and beautifully written. It is a condemnation of the brutal senselessness and stupid waste of war. Through its fascinating scenic technique it paints detailed, intimate pictures of tents on the French battlefield, spa towns in Germany, the Inns of Court in the City, and English country estates, and it peoples these places with convincing characters who stay in the mind, especially Sylvia and Christopher Tietjens.

This Issue

March 24, 2011