1.

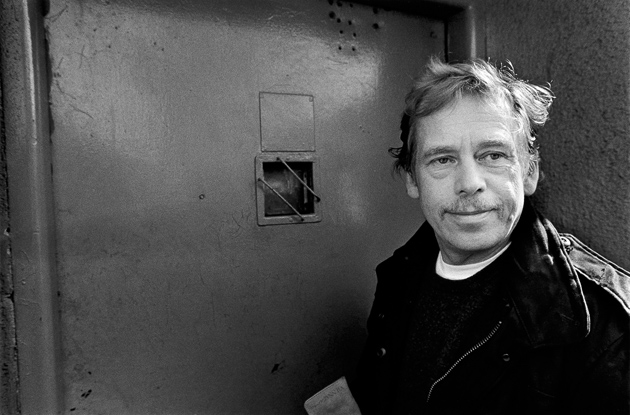

The five days following Václav Havel’s death on Sunday, December 18, at his country house, Hrádeček (“the little castle”), were unique in modern Czech history. Almost as soon as the news broke, people began gathering spontaneously in public places, not just to pay their respects, but to talk about what it was they had just lost in the passing of this modest, complex, and courageous man who had been their first post-Communist president.

In villages and small towns, the local church was often the gathering place of choice; in larger towns, it was the public squares; in Prague, locales associated with Havel—the plaque on Národní Třída honoring the demonstrators of November 17, 1989, who had set off the Velvet Revolution; Havel’s post-presidential office two blocks away; his villa on Dělostřelecká Street not far from the Prague Castle; the castle itself—became candle-lit shrines. But it was in Wenceslas Square—the locus of so many joyful and tragic events that shook this country over the past centuries—that the largest crowds gathered to lay a sea of flowers and flags and handwritten thank-you notes and votive candles at the foot of the equestrian statue of Saint Wenceslas (Svatý Václav in Czech, the “good king” of the Christmas carol who is also Havel’s namesake).

The mourners—if that’s the proper word to describe them, for there were few displays of outright grief—were of all ages and backgrounds and everyone brought memories of their own. The elderly could look around them and perhaps recall the grim prelude to World War II as, in March 1939, columns of Nazi troops and motorized brigades occupied this very same square, and then the country, when Havel was the two-and-a-half-year-old son of a wealthy Czech property developer. The middle-aged could recall August 1968, when Soviet tanks rumbled through the square, crushing the Prague Spring in which Havel, now a prominent young writer, had been a gadfly to the reformers.

And almost everyone over thirty could remember Wenceslas Square during the events of 1989, which began in January with clashes between protesters and police (when Havel, the dissident, and others had been arrested and imprisoned) and ended in the jubilant November demonstrations that toppled the Communist regime, and thrust this same man into the forefront and, ultimately, into the post of president where he remained, first as head of Czechoslovakia, and then of the Czech Republic, for almost thirteen years.

Since then, on the rocky road to democracy and a working market economy, Havel had been with the Czechs, sometimes an inspiring figure, sometimes an annoying scold, articulating his vision for the country, for Europe, and for the world. It was a vision based on a democratic politics underpinned by a strong civil society and rooted in common decency, morality, and respect for the rule of law and human rights; a politics that sought to transcend racial, cultural, and religious differences by articulating a “moral minimum” that Havel believed existed at the heart of most faiths and cultures and that would provide a basis for agreement and cooperation without sacrificing the unique gifts that each person, each culture, and each “sphere of civilization” could bring to enrich modern life.

His vision held great appeal in the world at large. But in the rough and tumble of domestic politics, Havel’s words, once powerful enough to shake the foundations of the totalitarian state, sometimes seemed helpless to stem the rise of racism and corruption, or to slow the inflation that plagued so many who lived on fixed incomes or pensions, helpless to halt the headlong rush to separation from Slovakia that tore the country apart in 1993.

Since then, the diminished Czech political scene had been dominated by Václav Klaus, a man with a different view of what democracy meant. Freedom, in Klaus’s view, was something bestowed upon the people by their governors and guaranteed by their elected representatives. Citizenship meant voting once every four years and then leaving civic and economic matters for government and the marketplace to sort out. It was a view that to many, including Havel, seemed suspiciously like the old centrist regime dressed up in new, market-minded, quasi-populist rhetoric.

The conflict between these two men and their competing visions dragged on, unresolved, for many years, casting a pall over domestic politics that neither man seemed willing, or able, to dispel. Havel’s second term as Czech president—from 1998 to 2003—was marred by health problems, by scurrilous personal attacks on him and his second wife, Dagmar, and by political missteps that made him seem tired and out of touch. When his mandate ended in 2003, despite his enormous achievements—most notably bringing the Czech Republic into NATO and preparing the ground for its successful entry into the EU—he left office with little fanfare, and few public displays of affection or gratitude.

Advertisement

Thus the crowds that spontaneously filled the streets when he died—the largest since the Velvet Revolution—were all the more astonishing. It was as though the Czechs had only belatedly begun to grasp the magnitude of their loss, and the greatness of the man who had unobtrusively slipped out of their lives.

2.

Toward the end of To the Castle and Back, his unconventional presidential memoir, in a section datelined “Hrádeček, December 5, 2005,” Havel confronts the question of his own death. “I’m running away,” he writes.

What I’m running away from is writing. But it’s more than that. I’m running away from the public, from politics, from people. Perhaps I’m even running away from the woman who saved my life. Above all, I’m probably running away from myself.

He finds himself constantly fretting about the tidiness of the house, as though he were expecting a visit from someone “who will really appreciate that everything is in its proper place and properly aligned.” Why this obsession with order?

“I have only one explanation,” he says.

I am constantly preparing for the last judgment, for the highest court from which nothing can be hidden, which will appreciate everything that should be appreciated, and which will, of course, notice anything that is not in its place. I’m obviously assuming that the supreme judge is a stickler like me. But why does this final evaluation matter so much to me? After all, at that point, I shouldn’t care. But I do care, because I’m convinced that my existence—like everything that has ever happened—has ruffled the surface of Being, and that after my little ripple, however marginal, insignificant and ephemeral it may have been, Being is and always will be different from what it was before.

“All my life,” he went on,

I have simply believed that what is once done can never be undone and that, in fact, everything remains forever. In short, Being has a memory. And thus, even my insignificance—as a bourgeois child, a laboratory assistant, a soldier, a stagehand, a playwright, a dissident, a prisoner, a president, a pensioner, a public phenomenon, and a hermit, an alleged hero but secretly a bundle of nerves—will remain here forever, or rather not here, but somewhere. But not, however, elsewhere. Somewhere here.

Havel died peacefully in his sleep in the presence of Sister Veritas, one of a small team of nursing nuns—“sisters of mercy”—who took turns looking after him in the final months of his life. Like so many of those who had worked closely with Havel, Sister Veritas had nothing but praise and admiration for the man she was caring for. She told a Czech Web newspaper, Aktuálně.cz, that he was reconciled to being near death, and was determined to die at home. “He’d spent long periods in hospitals,” Sister Veritas explained, “and that environment bothered him. He liked his own things, his own order, his own people around him. He liked flowers and regularly bought gladiolas that he was fond of looking at. They reassured him that he was being well looked after. He wanted some control over his own destiny, and he had that to the very end.”

The day before he died, Havel, ever the stage manager, made elaborate plans to celebrate Christmas at Hrádeček. He went to bed, but had trouble sleeping, and Sister Veritas spoke to him several times during the night. In the morning, they spoke again shortly after 7:00 AM. “The last words I heard him say were: ‘I want to sleep a little longer. Come back in an hour or so.'” About 9:30, Sister Veritas returned to his room and noticed that his breathing had become shallower. “Suddenly, between 9:45 and 9:50 AM, the moment came when he no longer took a breath. It was like a candle going out, so silent.”

Sister Veritas and Havel’s wife, Dagmar, took turns sitting with him until the next morning. A death mask was arranged, and then his body was put in a modest wooden coffin and driven to Prague, where it was placed in a church in Prague’s Old Town that the Havels had renovated as a performance and exhibition space and renamed Prague Crossroads. Here it lay from Monday to Wednesday, the coffin bare and flagless, while an honor guard of friends and colleagues, along with his faithful “pistoleers”—as he called his bodyguards—stood watch as thousands filed by, over two days and two nights, to pay their respects. There was not a whiff of officialdom or high ceremony about this part of the leave-taking. People were saying good-bye to Havel the dissident, the writer, the bon viveur, the friend, the ex-con and ex-president, Havel the man.

Advertisement

All that changed on Wednesday morning, when the casket was transferred to a hearse and slowly driven through the bitterly cold streets, followed first by Dagmar Havlová and her daughter, then Havel’s brother Ivan and his wife, and then by tens of thousands, a crowd so large the central Prague cell-phone network temporarily crashed. The procession wound out of the Old Town, across the Charles Bridge, and up the hill to a square not far from the Prague Castle, where official protocol took over. It was now about Havel the president, Havel the hero, Havel the warrior for human rights, Havel the statesman. The coffin was draped in a large Czech tricolor and placed on the same gun carriage that had borne Czechoslovakia’s first president, Tomáš G. Masaryk, to his grave in September 1937. Then it moved, slowly and ceremonially, drawn by six jet-black horses through the gates and courtyards of the castle to Vladislav Hall, where Havel had first been sworn in as Czechoslovak president twenty-two years before. It was set on a high catafalque, no longer the modest casket, with a uniformed honor guard and surrounded by a sea of large wreathes.

It was here that President Klaus delivered the first of two eulogies, much anticipated because people were genuinely curious about what Havel’s arch rival, who had scarcely uttered a good word about him in the past, would now say over his dead body.

Several people I talked to thought that Klaus’s speech was generous, and indeed, Klaus did say most of the right things. He recognized Havel’s courage, his willingness to suffer for his ideas, his service to the state, the way he had enhanced the country’s image abroad, and he called upon Czechs to follow his example. But later, when I studied his remarks more closely, there was something curious about them too. Klaus frequently referred to Havel’s achievements in the passive voice, as though what Havel had accomplished had somehow just happened, without any volition on his part. “His life reflects and expresses a large part of the very complex and problematic twentieth century,” Klaus said. “The war, the postwar period, the arrival of communism, the thaw of the 1960s, normalization, the fall of communism, the building of a new democracy, the collapse of the federation, and the inclusion into the European integrational structures. His life reflected all of this.”

Klaus’s account of Havel’s significance to the Velvet Revolution was even odder: “Václav Havel became a symbol of the beginning of the transformation,” Klaus said, “and people projected their hopes onto him. He also played an important role through the concrete steps he took so consciously and decisively to support those of us who did not see in 1989 simply another 1968 or another attempt to create socialism with a human face.” It was as though Klaus, aware of the momentousness of the occasion, were reserving a top spot for himself in an eventual rewriting of history. In that sense, he was true to form.

3.

The official requiem mass for Václav Havel, held in Prague’s largest cathedral, St. Vitus, in the presence of representatives and heads of forty-two different countries (with the conspicuous absence of anyone from the Kremlin) and a thousand invited guests, was a masterpiece of last-minute logistics. Klaus’s office, as his chief of protocol, Jindřich Forejt, later admitted, had absolutely no plans in place for a state funeral, despite the fact that Havel had been in palliative care for several weeks before his death. No matter: they got down to business, and in four short days pulled together a beautifully orchestrated two-hour ritual send-off that I imagine Havel himself could have admired and perhaps even enjoyed, complete with the Dies Irae from Dvořák’s Requiem, Handel’s Hallelujah chorus, a high mass, and a dozen small personal touches that softened the hard liturgical edge of the proceedings. The archbishop of Prague, Monsignor Dominik Duka, who had spent fifteen months in the same prison as Havel in the 1980s for his activities in the underground church, recalled the chess tournaments he’d played with Havel in jail. Havel had organized them, he said, not because he was particularly fond of chess, but to provide Duka cover for his secret prison masses—yet another example of Havel’s dramaturgical skills and generosity of spirit.

Klaus delivered a second eulogy, and the former US secretary of state Madeleine Albright gave a short encomium to Havel in fluent Czech. But for many of Havel’s old friends, the high point was a brief address by the current Czech foreign minister and President Havel’s former chancellor, Karel Schwarzenberg, who is thought to be a front-runner in the Czech presidential elections next year, when Klaus’s term is up.

Schwarzenberg directed his remarks to those who were not in the cathedral, those, he said, whom protocol had forgotten, who had stood by Havel in the hard times, the

students, who were the backbone of the Civic Forum…citizens in Brno, in Pilsen, in Ostrava or in Česke Budějovice who believed in him and created democracy in this country.

He went on to mention the absent Slovaks for whom Havel had been president for more than two years. And he gestured to the underground musicians who called Havel their “Chief,” an expression that in Czech evokes images of Geronimo or Crazy Horse. Havel had no need of high office for his leadership to be recognized, Schwarzenberg said. “He was a chief by his very nature. It was enough for him to be present in the room.”

When the requiem was over, the coffin, still draped in the flag, was carried out of the cathedral and taken to the Strašnice crematorium, where close friends of Havel said their final farewells. That evening, the Lucerna entertainment complex on Wenceslas Square, built almost a century ago by Havel’s grandfather, was filled with revelers of all ages, who came for a huge wake, sponsored by his brother Ivan, who is part owner of the place, to celebrate their “rock’n’roll president.” It was a joyous occasion. Bands and musicians who had had strong connections with Havel were invited to perform, and actors performed a shortened version of his very first play, The Garden Party.

For me, the highlight of the evening was a performance by the Plastic People of the Universe, a band I had once played with, and whom Havel had championed back in the 1970s when they were on trial for disrupting the social order. Havel was one of the first of his circle to recognize the importance of the Plastic People’s refusal to be shut down, and the alliance forged between the dissident intellectuals and the musical underground led directly to the formation of Charter 77 and the Committee to Defend the Unjustly Prosecuted, for which Havel spent over four years in prison. That the Plastic People were still playing thirty-five years later was only one of many apparently miraculous things that could be traced directly back to the man who was no longer there.

4.

In a week in which the Czech newsstands were flooded with special commemorative editions of magazines and newspapers devoted to Havel’s passing, there was scarcely an aspect of his life and ideas that was not mulled over and parsed for deeper meaning, or recalled in pictures. The most iconic of those pictures—a shot of Havel with his back to the camera, walking toward the ocean—was turned into a poster and widely displayed around Prague, along with a quotation expressing one of Havel’s most deeply held beliefs: “Hope is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out.”

A ringing statement, but it was not quite in focus. What Havel meant by “something”—as his other formulations of the same belief make clear—was action. All his life, Havel lived by the belief that if you wanted something to happen, you had to do something to make it happen, and damn the consequences, including arrest and prison, and possibly even death. Speaking about the early days of the post-Stalin thaw, he once said: “The more we did, the more we were able to do, and the more we were able to do, the more we did.” It is a fine summary of his attitude, and, in a sense, his legacy. Havel was continually pushing the boundaries of the possible, and in doing so, he was able to create space for others to follow.

This quality is what, quite properly, put him in the same league as Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King Jr. But what put him in a league of his own is the corollary: you act not to achieve a certain outcome; you act because it is the right thing to do. That is what he meant by “living in truth,” a notion he explores in some depth in his most radical and enduring work: The Power of the Powerless.

Like many great Czechs before him, Havel insisted on the importance of truth, but with a difference. “Truth and love,” he was fond of saying, “must prevail over lies and hatred.” He was often ridiculed for what seemed like a Hallmark sentiment (“Why love?” people asked), but he defended the slogan by referring to one of his greatest insights: truth, by itself, is a malleable concept that depends for its truthfulness on who utters it, to whom it is said, and under what circumstances. As a playwright, Havel turned this insight into a dramatic device: in most of his plays, the main characters constantly lie to one another and to themselves, using words that, in other circumstances, would be perfectly truthful. Truth by itself is not enough: it needs a guarantor, someone to stand behind it. It must be uttered with no thought for gain, that is, in Havel’s words, with a love that seeks nothing for itself and everything for others.

We are close to religious territory here, and indeed, in the week of leave-taking in Prague, I heard many discussions about Havel’s true beliefs. Was he a Catholic and, if not, was the high mass in St. Vitus’s Cathedral the right way to send him off? Yes, replied some, he had been raised a Catholic and been confirmed as a young man. Sister Veritas said she felt that Havel was “with God” more profoundly than many observant Catholics, but she admitted that he had neither asked for nor received the last rites before he died. One of his last conversations was with the Dalai Lama, whom he considered a spiritual guru. But in the circumstances, such questions seemed inconsequential, even scholastic. Havel was a deeply spiritual man who expressed his spirituality, if that is the right word, almost entirely through his actions in the world.

Not all of those actions stand up to closer scrutiny. Havel’s endorsement of the invasion of Iraq, nuanced though it was,* angered many of his supporters. Tony Judt, in a September 2006 article in the London Review of Books, lumped Václav Havel and Adam Michnik in with “America’s liberal armchair warriors”—a group in which he included people like Christopher Hitchens and Michael Ignatieff and whom he called Bush’s “‘useful idiots’ of the War on Terror.” The term must have been particularly stinging to Havel since it was originally applied to Western intellectuals who supported Stalin without really understanding the implications of that support. When he was asked by the Czech weekly Respekt to respond to the criticism, he replied that despite the bogus justification and the questionable outcome of the invasion, he was glad to see Saddam Hussein gone. It was not a persuasive answer, but then Havel was never one to back down from a position once taken, and he never took a position on anything simply because he thought it would play well with the public.

A case in point was his position on the expulsion of almost three million Czech Germans from the country after World War II. Havel had always considered this expulsion both morally wrong and politically disastrous, because it was an inhuman act carried out on dubious legal and moral grounds, and because it established a precedent that he felt had prepared the way for the Communist putsch in 1948. And though he later claimed that he had not, as president, offered any formal apologies to the Germans, he certainly believed that some sort of compensation was in order for those expelled, perhaps in the form of Czech citizenship. His position caused an uproar at home that has still not entirely died down, but he stuck to his guns.

Havel’s generosity toward Sudeten Germans points to one of his finest, and most radical, qualities: his capacity for forgiveness. “So many horrible things have happened to this little nation in its relatively short history,” someone told me recently, “and Havel knew that the only way to break out of that lethal cycle of hatred and vengeance was to forgive those who have wronged us. If,” he added, “they ask to be forgiven.” During the Velvet Revolution, Havel, contrary to the position later taken by Václav Klaus, had spoken out strongly for reconciliation with Communists who were willing to step out of their ideological straitjackets and embrace the new democracy. On the other hand, as president—again, unlike Klaus—he refused to have anything to do with the Communist Party because, he said, it had never apologized for its forty years of terrible misrule.

While in Prague for Havel’s funeral, I became convinced of something that I had, in fact, always known: that the true measure of Havel’s greatness was not the respect he could command from the powerful and the famous, but the affection he inspired in so-called “ordinary people” whose lives he had touched and enhanced: people like Sister Veritas or former staff members, or the policemen who had once been assigned to follow him around. In the end, Havel will be remembered by those who came within his orbit for his unfailing decency and politeness, qualities still sadly lacking in Czech political culture. Havel instinctively understood that the old system thrived by stripping people of their dignity, by systematically humiliating them in a thousand little ways that rendered them powerless. His way of treating others, even former opponents, with civility helped to restore that dignity and that power, and it was through thousands of such small acts, as much as through his writing and his towering example, that he brought his society closer to healing.

—January 10, 2012

This Issue

February 9, 2012

The Wrong Leonardo?

The Republican Nightmare

-

*

See my article “A Wonderful Life,” The New York Review, April 10, 2003. ↩