One morning in 1740, a thin young man could be seen heading down the steep cobbled road leading from the Kashmir Gate of the Punjabi hilltown of Guler, and making for the banks of the fast-running river Ravi far below. Nainsukh was just short of thirty, with a slightly hesitant expression, buckteeth, and a downy mustache. He had just been appointed as court miniature painter at the neighboring Himalayan princedom of Jasrota, and in his baggage were the sketchbooks, albums, boxes of pens, squirrel hair brushes, and stone-based pigments such as lapis-blue and malachite-gray that Indian miniature painters used to create their dazzling colors.

It was in Jasrota that Nainsukh—“Delight of the Eye”—began producing the work that led to him today being generally regarded as the greatest of eighteenth-century Indian painters. Nainsukh brought together all the precision and technically exquisite detail of the Mughal tradition, the bright colors of Rajasthani painting, and the bold beauty of early Pahari art—the art of the Punjab hills. To all this he added a humor and a humanism, a refinement, and above all a precise, sharply observant eye that was entirely his own. He broke free from the formality of so much Indian court art to explore the quirky human reality, stripping down courtly conventions to create miniatures full of living and breathing individuals, portrayed somewhere on the boundary between portraiture and caricature, like an Indian Brueghel, only much more elegant and refined.

Even in his large crowd scenes, there are no stock figures: everyone—each courtier, each village beauty, each gardener—is shown in portrait form as a real person, with all their oddities and quirks. Nainsukh’s art—he first learned in the family atelier at Guler, apprenticed to his father Pandit Seu, and worked alongside his elder brother Manaku, then in Jasrota for his most discerning patron, Raja Balwant Singh—is for many of his admirers a summation and climax of the Indian miniature tradition.

But it was not just that Nainsukh was a brilliant miniaturist. His work gives a unique insight into the relationship between an Indian artist and his patron, between a court and a court painter. Raja Balwant Singh and Nainsukh seem to have had an unusually close relationship and must have been of roughly similar ages. The chronology of Nainsukh’s miniatures leads us from the family sketches and self-portraits of the artist’s own adolescence, through the move to Jasrota, his first commissions for Balwant’s father, Mian Zorawar Singh, and on to his first images of Balwant, his future patron. We see Balwant as a good-looking dandy of a young prince in all his silken finery, sitting back on a bolster in a gorgeously striped robe as he puffs away at his water pipe, his falcon glaring from his wrist. Sometimes he is shown as a handsome youth standing regally on a terrace, a sword in one hand, a sweet-smelling narcissus in the other.

Then Balwant succeeds to the throne and we follow the young men of the court on winter evening rides through mustard fields, serenaded by lovely singers; on hawking and lion- and tiger-hunting trips (see illustration on page 75); and to music evenings and dance performances. There are occasional images of quiet evenings where the raja, wrapped in a shawl, sits in front of a blazing fire with a glass of some warming beverage. We also see the painter standing, bowed in reverence behind his enthroned patron, as the connoisseur-prince carefully examines a new devotional painting; the court musicians and attendants look on to gauge his reaction. We even see such everyday yet oddly intimate scenes as Balwant Singh’s visit to the palace barber to have his beard trimmed.

Then, slowly, the story darkens. A group of villagers assemble, led by an aggressive-looking Brahmin. There is some sort of palace coup; the raja is seen standing alone on his battlements, isolated from all. Years of exile follow as Balwant Singh travels the hill country, sheltering in villages, as his court artist, his last confidant, shares his exile. Nainsukh paints him at night, warming his hands on a rustic bonfire among a group of villagers, or writing letters in his tent, careworn and half-naked in the summer heat of his day, with only one attendant left to him. Finally Nainsukh shows himself escorting his patron’s pot of ashes for immersion in the Ganges at Hardwar. It is a uniquely sad and intimate sequence that has no parallel in Indian art.

Yet for all his singularity, Nainsukh was not unique: he was instead painting at a time when the Punjab hill states of the Himalayan foothills in the late eighteenth century were going through a period of astonishing creativity. This great blossoming took place soon after the puritanical Mughal emperor Aurangzeb had withdrawn his patronage from the great Mughal atelier in Delhi toward the end of his reign, on the grounds that depicting the human form was forbidden in Islamic law. As the spirit of austere orthodoxy took root across the Mughal dominions, some of the finest painters, dancers, and musicians in the capital were forced to migrate, looking for patronage in the regional courts that had sprung up to fill the void left by the declining empire. Many of the greatest Mughal painters seem to have come originally from Kashmir and the Punjab hills; as work ran out in Delhi, they returned home to courts like Guler and Jasrota in search of employment. As a result, small remote mountain fortresses suddenly blossomed with artists trained with metropolitan skills, each family of painters competing with and inspiring each other in a manner comparable to the rival city-states of Renaissance Italy. In this scenario Guler and Jasrota can be compared to San Gimignano and Urbino, small but wealthy hill towns ruled by a court with an unusual interest in the arts.

Advertisement

Yet while the greatest artists of Italy had their lives recorded by Vasari, and the biographies of even the most minor ones have long been the subject of research by art historians, the situation in India is much more obscure. The simple fact is that most Indian paintings are still anonymous. Nainsukh remains today the only Indian miniature painter to be the subject of a full-length study. The reconstruction of his life, and those of other Indian masters, has taken place surprisingly recently.

Over the last forty years, a small group of scholars of Indian art has been closely analyzing signatures and inscriptions on miniatures, as well as other sources such as palace archives and land registers. In this way they have recovered the names and in some cases tantalizing fragments of biography for dozens of painters, many of whom formed dynasties of artists working for successive generations of sultans, rajas, and emperors—the human story behind the stylistic history of Indian painting.

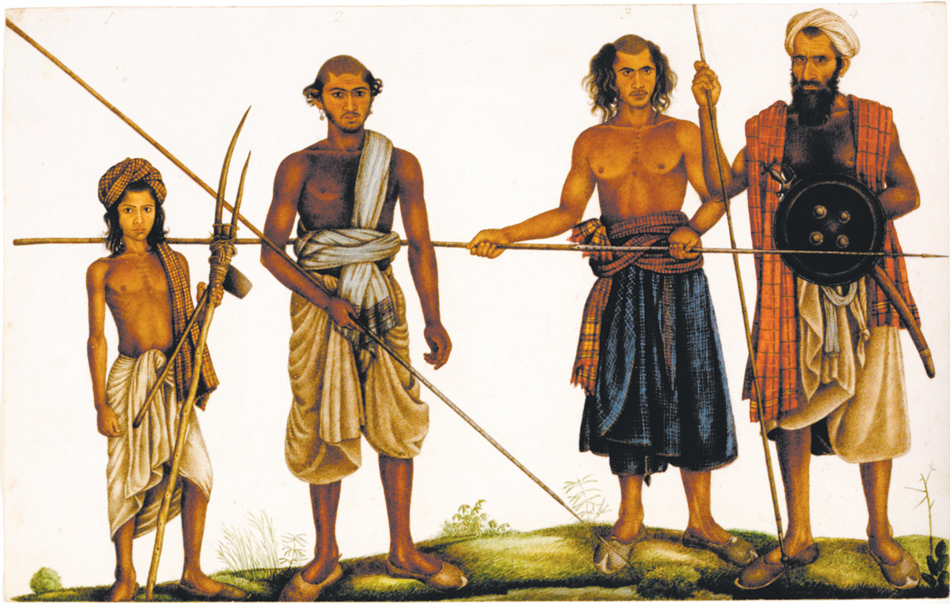

The difficulty of such art-historical sleuthing is compounded by the fact that many Indian painters came from the relatively humble carpenter’s caste and seem to have regarded their work as part of a long craft tradition; indeed in ancient India painters were ranked alongside lowly musicians and dancing girls. Few perceived themselves as great artists, though from the seventeenth century onward there is evidence that the greatest masters were highly mobile and the subject of bidding wars between rival patrons in competing courts across the region.

The man who has probably done more than anyone to bring the Indian masters back from anonymity is India’s preeminent art historian, Professor B.N. Goswamy of the University of Chandigarh. In 1968, he wrote a groundbreaking article, “Pahari Paint- ing: The Family as the Basis of Style.” Employing a combination of remarkable detective work, intuition, and connoisseurship, Goswamy managed to bring together the evidence from inscriptions on miniatures with innovative new sources.

Inspired by the picture of Nainsukh escorting the ashes of Raja Balwant Singh to Hardwar, he looked into the eighteenth-century pilgrim records kept at the holy town where the Ganges leaves the Himalayas and flows into the plains. There he found vital details of genealogy that allowed him to reconstruct the entire family network of Pandit Seu, Nainsukh, and Manaku, and their many miniaturist grandchildren and cousins. He showed how the family shared a common artistic style, but their mobility between different centers of patronage effectively made nonsense of the existing system of categorizing miniatures by schools or workshops and centers of production. What was important, Goswamy showed, was not where a particular miniature painting was produced, or even who the patron was, but instead which artist, or family of artists, was holding the brush. Court styles could vary hugely, depending on who was at work; but different families shared common training and techniques and stylistic idiosyncrasies.

By 1990 Goswamy had extended his research techniques to include all the other masters of Pahari painting—the great artists of the Punjab hills. Along with the Swiss art historian Eberhardt Fischer, the director of the Rietberg in Zurich, he produced a major show that completely rewrote the history of the art of the Punjab hills, recategorizing it by family and individuals, rather than courts. Finally, last year, Goswamy and Fischer, aided by the former director of the Freer Gallery in Washington and great specialist in Mughal painting Milo Beach, extended their work to encompass the entire history of the Indian miniature tradition.

This epic project culminated in “Wonder of the Age,” one of the largest and most spectacular exhibitions of Indian painting ever put on show, which traveled from Zurich to the Metropolitan Museum in New York, along with which was published an extensive two-volume catalog, the work of thirty scholars, entitled Masters of Indian Painting. The result was a complete revelation, and a dramatic and encyclopedic reevaluation of the human reality behind Indian painting. What Nainsukh had done for the patrons of his day, Masters does for the painters. Suddenly a gallery opens up before us that is filled with real living individuals, each rendered in silhouette, yet full of life and vitality, and each capable of independent thought and action.

Advertisement

From literary sources it is clear that ancient India had a highly developed tradition of painting and portraiture, which continued to flourish until the end of the first millennium AD; indeed an entire manual survives holding forth on the art of landscape painting. But with the exception of the Ajanta caves frescoes, inland from modern Bombay, dating from the sixth century, and the wall paintings of the remote thirteenth-century Buddhist monastery of Alchi in Ladakh, on the borders of Tibet, and a few other fragments—at Sigriya, in Sri Lanka, and at Ellora, Bagh, and Tanjore—almost nothing of these riches has survived.

Yet these scattered fragments are more than enough to indicate the quality and sophistication of what has been lost. The paintings at Ajanta—telling the Jataka stories of the Lives of the Buddha, painted onto the walls of a chain of Buddhist caves excavated in a remote horseshoe of cliffs—are of such supreme elegance and grace that they clearly represent a last fragment of a lost golden age. They use chiaroscuro and foreshortening, and are fresh and spontaneous, yet full of grace, beauty, and equilibrium. They show a mastery of composition, bodily modeling, and color harmony, while reveling in action and drama. They also subtly explore a wide variety of human emotions.

Although the images were presumably intended for a monastic audience, interspersed with the occasional passing pilgrim, what is striking to the modern viewer is the unexpected yet heady mixture of the sacred with the sensual. The Buddha tends to be shown not just in his monastic milieu, after his Enlightenment, but in the courtly environment in which he grew up. Here among handsome princes and nobles, dark-skinned princesses languish lovelorn, while heavy-breasted dancing girls and courtesans are shown nude but for their jewels and girdles, draped temptingly amid palace gardens and court buildings. These women conform closely to the ideas of feminine beauty propagated by the great fifth-century Gupta-era playwright Kalidasa, who writes of men pining over portraits of their lovers, while straining to find the correct metaphors to describe them:

I recognize…your expression in the eyes of a frightened gazelle; the beauty of your face in that of the moon, your tresses in the plumage of peacocks; and the play of your eyebrows in the faint ripple of flowing water…alas! Timid friend—no one object compares to you.

The astonishing beauty of the Ajanta frescoes makes the losses all the more tragic. The great Buddhist monasteries of India were renowned for their multistoried libraries, with their vast holdings of illustrated manuscripts; today not only is the name of every single painter forgotten, but almost every last fragment of Indian painting on bark and palm-leaf manuscripts dating from this period has been destroyed. Practically everything was eradicated in the cultural holocaust that accompanied the first Turkic invasions of northern India in the thirteenth century. In these conquests an enormous corpus of Buddhist knowledge was lost through Islamic iconoclasm in an orgy of wreckage comparable to the burning of the Alexandrian Library, or the destruction of the centers of learning in Persia by Genghis Khan’s Mongol hordes.

Through these ashes, however, emerged the first shoots of Indo-Islamic art, tendrils that would later blossom into a harvest of great richness. The Muslims brought with them the technology of papermaking, and by the fourteenth century, many of the new sultanates that had sprung up in northern and central India had flourishing centers of manuscript illustration. The styles of some of these early works were provincial echoes of the great work then being produced by Persian master artists like Bihzad in Timurid Persia and Afghanistan.

Such was the style used in the Central Indian hill fortress of Mandu where illustrations were made to accompany the Ni’matnama, “The Book of Delights,” the royal recipe book of Sultan Ghiyath Shahi (1469–1500). The illustrations show his favorite recipes not just for food and drink but also for perfumes, betel chews, and aphrodisiacs. At the same time other sultanate manuscripts began to fuse imported Timurid styles with indigenous Indian techniques. You can see the beginnings of this in another Central Indian manuscript where the Persian epic, the Shahnama, is illustrated in a style that borrows many elements from the Jain manuscripts then still being painted in the temples and monasteries of Gujarat.

This process of fusion and syncretism was hugely accelerated by the arrival from Central Asia of the Mughal dynasty in India in 1560, and an extraordinary commission made by the third of the Mughal emperors, Akbar (1452–1605). He ordered his court artists to produce a series of large-scale cloth-panel illustrations, which would be held up as visual aids during the recitation of his favorite epic, the Hamzanama. This is a rollicking action-filled Persian miscellany of folk tales, legends, religious discourses, and entertaining fireside yarns similar in spirit to the yarns of The One Thousand and One Nights, which over time had come to gather around the epic story of the travels of the hero Hamza ibn Abdul-Muttalib, the father-in-law of the Prophet.

Before these illustrations were commissioned, the Mughal miniature painting atelier contained only two known artists—there may have been more. These were Mir Sayyid Ali and Abdus Samad—two of the first names of artists we know in the history of Indian art—whom Akbar’s father, the emperor Humayun, had lured to India from Persia. Since their arrival, they had between them produced a few entirely Persianate pictures in Agra. Akbar changed the nature of the Mughal atelier forever by commissioning no fewer than 1,400 large-scale panel illustrations to the Hamzanama—the largest single commission in Mughal history. The project forced the atelier to train more than one hundred Indian artists—many of them, it seems, Hindu and Jain painters from Gujarat—in the Persian style, as well as troops of poets, gilders, bookbinders, and calligraphers. The resulting volumes took more than fifteen years to produce and in the process gave birth to an independent Mughal miniature tradition. In these can be seen a wonderful combination of Persian, Central Asian, and Indian styles, and a revolutionary leap forward from all the work that preceded it.

While the Hamzanama paintings were relatively large images designed to be seen from a distance as a visual aid to the recitation of the epic, most of the images subsequently produced in Mughal workshops were small-scale rectangles of intensely painted manuscript, gemlike in their detail and color, and designed to be looked at in an album, passed from hand to hand. It is a private and intimate art, produced in the court atelier by a group of skilled artists that seems to have moved from fort to fort, camp to camp, along with the court and emperor. There are several images of the painters at work that show the setting from which the images came. “An ustad [master]” is “in complete control,” writes Goswamy, “as pupils ply their brushes under his stern eyes, workmen burnish sheets of paper, calligraphers [pore] over their texts, attendants stand about as if waiting for commands….”

The Mughal studios seem to have been busy places where order reigned: master artists laid down rules; the consciousness of hierarchies was in everyone’s minds; painters of different extractions, drawn sometimes from different parts of the country or outside, worked or at least sat together; commissions were handed down and scrupulously carried out.

Yet real stars of the atelier were by virtue of their talent distinguished figures at court and as such free agents. As Akbar’s biographer, Abu’l Fazl, wrote in the A’in-i Akbari (his record of the emperor’s court):

More than a hundred painters have become famous masters of the art, whilst the number of those who approach perfection, or those who are middling, is very large…. It would take too long to describe the excellence of each. My intention is “to pluck a flower from every meadow, an ear from every sheaf.”

Over the last thirty years, scholars have shown how master artists of the court could follow their own whims and the needs of their careers to move from court to court. Perhaps the most spectacularly mobile was the Persian painter Farrukh Husayn. In the early 1580s, he moved from the service of Persian Safavid Shah Khodabanda in Isfahan, where he was an established star of the court, to Kabul, where he worked for the emperor Akbar’s half-brother. By 1585 he was in Lahore where he was honored with the title Beg and a mention in the official biography of Akbar as one of the two greatest artists at court.

But this restless genius had still not found what he was looking for. By 1590, he was attached to the most esoteric court in India, that of Ibrahim Adil Shah II in Bijapur in south-central India (see below). Early in his reign this Muslim potentate gave up wearing jewels and adopted instead the rosary of the Hindu holy man. In his songs he used highly Sanskritized language to shower equal praise upon Sarasvati, the Hindu goddess of learning; the Prophet Muhammad; and the Sufi saint Gesudaraz.

Farrukh Beg, as he was now known, had started painting in a flat and purely linear Persian style. He then moved toward the more elaborate style of the Persian Timurid dynasty in Afghanistan, before adopting in middle age the more realistic modeling of the Mughal atelier. In Bijapur he found himself changing his style and the content of his paintings yet again, to produce suitably mystical, otherworldly, and indeed almost psychedelic images of the Goddess Sarasvati for this most heterodox of courts. Yet his travels were not over. Abandoning Bijapur and the radically surreal, perspective-free chromatic experiments he had indulged in there, he returned to Agra where he died in the service of Akbar’s son Jahangir, having again reverted to a more mainstream Mughal style.

The reigns of Jahangir and his son Shah Jahan—who commissioned the Taj Mahal in the mid-seventeenth century—took place during the artistic highpoint of the Mughal atelier, and with it the moment of greatest celebrity for the masters at court. Jahangir awarded his two master artists, the brilliant animal painter Mansur and his rival Abu’l Hasan, the titles Nadir al-Asr, “Wonder of the Age,” and Nadir al-Zaman, “Wonder of the Times.”

The violent seizure of the throne from Shah Jahan by his son, the austere and iconoclastic puritan Aurangzeb, in 1658, created a quite different type of mobility among the artists of the Mughal court as patronage ran out in the capital. As one of the contributors to Masters, Navina Haidar, shows in a brilliant essay, the artists of the court were sufficiently celebrated to be able to move where they wished: the painter Bhavanidas, for example, shifted in 1719 from Delhi to the Rajasthani court of Kishangarh, just beyond Jaipur.

In one of the most illuminating essays in the book, Goswamy shows how different were the systems of production of art in the courts of Rajasthan and the Punjab hills from those employed in the Mughal capital: “There seem to have been no ‘workshops,’” he writes,

in the sense of halls or buildings situated in the capital city where ustads sat presiding over all that happened…. [Instead] nearly everything there appears to have been made within families of painters: “family workshops,” so to speak, not necessarily located in the state capital or nearby, and not made up of artists of different extractions or backgrounds. Artists could be working in their family homes: a small town or a village, perhaps….

In the course of the eighteenth century, just as the Rajasthani and the Pahari ateliers were producing their greatest work in the north and west of India, in the east the British East India Company was transforming itself from a coastal trading organization into an aggressive colonial government, filling the power vacuum left by the implosion of the Mughal Empire. Yet initial contact between these two empires was surprisingly positive in Delhi: the first company “residents,” or ambassadors to the Mughal court, fell in love with Mughal culture and absorbed themselves in the life of the intellectual and artistic elite, wore Mughal dress, took Mughal wives, and became important patrons of Mughal painting, transforming the art of the capital in the process.

The best works produced under Company patronage—notably the Fraser Album—are unparalleled in Indian art. They also show a sympathy with the Mughal world quite at odds with stereotypes of colonial philistinism and insensitivity. The work produced by Mughal painters for British patrons is sometimes classified as “Company Painting,” but in the Mughal capital of Delhi it is impossible to make any meaningful distinction between “Company” and “Mughal” work as the same family of artists—notably the great Ghulam Ali Khan and his nephew Mazar Ali Khan—were working in very similar styles for Indian, English, and mixed-race Anglo-Indian patrons.

This late Mughal renaissance was destroyed forever in the bloodletting of the Great Uprising of 1857—the largest anticolonial revolt against any European empire anywhere in the world in the entire course of the nineteenth century. Its violent suppression by the East India Company was a pivotal moment in the history of British imperialism in India. It marked the end of both the company and the Mughal dynasty, the two principal forces that shaped Indian history over the previous three hundred years, and replaced both with direct imperial rule by the British government. But miniature painting outlived for a while the destruction of the Mughal court, continuing on in the princely courts of Rajasthan and a few other centers of culture, to die a slow and lingering death at the hands not of sepoys or vengeful British grenadiers, but of photographers.

Photography was introduced to the subcontinent in the early 1840s and by 1870 had totally altered the way the court painters went about their work. Included in the exhibition and its catalog are some portraits of the Maharana of Udaipur, strongly influenced by photographs, and some other work where black-and-white photographs have been hand-painted by miniature artists to make them more closely resemble miniatures.

The English artist Val Prinsep arrived in Delhi in 1877 to collect material for a picture the government of India wished to present to Queen Victoria as the subcontinent’s new empress. Soon after his arrival, Prinsep received a visit from the artists of Delhi, who he discovered now worked entirely “from photographs, and never by any chance from nature.” The same marvelous attention to detail is still on show—“their manual dexterity is most surprising”—as is the old fondness for bright, even lurid colors. But this was a last stand. By the end of the century many had given up and either become photographers themselves, or else retreated into producing crude reproductions of earlier Mughal work for the tourist trade. Miniature painting as a tradition was now dying.

When “Wonder of the Age” opened in New York in 2011, among other criticisms, some art historians complained about attributions: that manuscripts that were clearly the work of several hands were attributed to a single anonymous master to fit into the format of the show. For most of us, however, “Wonder of the Age” was simply the greatest show of Indian art ever mounted—room after room of spectacular masterpieces arranged chronologically by master artists, many of whose names had been rescued only recently from obscurity thanks to the scholarly detective work of Professors Goswamy, Fischer, and Beach and their international army of colleagues.

The two volumes published alongside the show, Masters of Indian Painting, have a similar stature. A summation of all the recent scholarship on the subject, with several hundred beautifully written scholarly essays and lavish illustrations, this enormous project, the fruit of a lifetime of detailed study, is itself a dazzling masterpiece of art-historical scholarship, and is likely to change forever the writing of Indian art history.