1.

After Andy Warhol died in February 1987, his will directed that a foundation should be set up in his name, funded with proceeds from the sale of some 95,000 pictures, prints, sculptures, drawings, and photographs left in his estate. As well as creating and endowing the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts provides financial support to artists and scholars, galleries, publications, and educational projects.

Warhol’s bequest made no provision for the authentication of his artwork. But in 1994 the foundation initiated work on a multivolume catalogue raisonné of Warhol’s art, in part because the project would “contribute to the stabilization of the market for Warhol works over time, thus having a direct benefit to the Foundation’s longterm goal of converting its Warhol works to cash at favorable prices.”1 In the following year the foundation’s directors set up an authentication committee to pass judgment on artworks attributed to him. Since then several large artist-endowed foundations have adopted the same policy. None have aroused the kind of controversy and ill feeling the Warhol authentication board attracted almost from the start.

Among the procedures that caused widespread disquiet was the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board’s standard practice of stamping the word “DENIED” in indelible red ink on the reverse of a rejected work. This became even more disturbing when collectors, art dealers, academics, and journalists raised questions about the methods of a board that operated in secret and refused to let owners know the evidence or reasoning behind their decisions, some of which were subsequently shown to be blatantly wrong.2

In the cases of which I was aware, when the validity of the board’s conclusions was challenged, its members declined to engage in any form of dialogue, either with owners of the works of art they deemed inauthentic or with those who had known or worked with Warhol.3 This policy left dissatisfied owners with little alternative but to speak to journalists or even to go to court, as happened in 2007 when the collector Joe Simon-Whelan brought a lawsuit against both the foundation and the board for refusing to authenticate a picture from Warhol’s 1965 series of Red Self Portraits.

The judge allowed the case, or most of it, to move forward. At the heart of the complaint was the board’s inability to explain why it had denied the authenticity of a virtually identical picture from the same series belonging to the collector and former art dealer Anthony d’Offay. D’Offay’s Red Self Portrait was signed, dated, inscribed in Warhol’s handwriting, and included in all three editions of the catalogue raisonné of the artist’s work published during his lifetime.4

The status of Simon-Whelan’s and d’Offay’s pictures could have been resolved by the board with the cooperation of both owners by convening a meeting of academics and art experts where the case for and against the series could be openly discussed. Instead, the foundation’s president, Joel Wachs, hired two of the most expensive law firms in the United States—Carter, Ledyard and Milburn, and Boies, Schiller and Flexner—to defend a decision by the foundation’s board that, as more of the facts about Simon-Whelan’s Red Self Portrait became known during the pre-trial hearings, began to look increasingly untenable.

What is initially striking about the transcripts of the witness depositions taken during the pre-trial hearings in the summer of 2010 is the performance of lead counsel Nicholas Gravante Jr. for Boies, Schiller and Flexner. Gravante is a formidable litigator. But I have searched the transcripts of his interrogation of Simon-Whelan in vain for any serious or sustained challenge to the factual evidence proving the picture’s authenticity presented by Simon-Whelan’s lawyer and backed up by creditable witnesses.

Instead, Gravante used his cross-examination to make personal attacks on Simon-Whelan. But Simon-Whelan’s lawyer, Brian Kerr, argued to the court—in my view, convincingly—that the accusations were no more than a diversion from the issue of the authenticity of Simon-Whelan’s painting. According to Kerr, the defense made these irrelevant accusations to ensure that there was no time to discuss the real issues raised by the case.5

Making many counterclaims, the foundation spent $7 million (including Mr. Gravante’s fees) to prevent Simon-Whelan from presenting his case in court. In the autumn of 2010 Simon-Whelan withdrew his suit, saying that he did not have the financial resources to continue. In a statement to the press made on November 15, 2010, he said:

I am deeply saddened that I was unable to reveal the truth in court, but when faced with threats of bankruptcy, continuing personal attacks and counterclaims, I realized I no longer stood a chance of proceeding further…. I had no other choice but to sign a document bringing the case to a close.

The document he signed said that he had “never been aware of any evidence, that Defendants have engaged in any conspiracy, anticompetitive acts or any other fraudulent or illegal conduct in connection with the sale or authentication of Warhol artwork.” He added, however, that he had “not agreed to deny the authenticity of the Red Self Portrait, as originally demanded by the Foundation,” and he continues to defend it.

Advertisement

It appeared that the foundation had won hands down. But in this instance, appearances were deceptive. A year later, on October 19, 2011, the chairman of the Andy Warhol Foundation’s board of directors, Michael Straus, announced that the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board was to close. Henceforth, he said, the foundation would use its huge financial resources exclusively for “grant-making and other charitable activities.”6 Less than a year after that, on September 5, 2012, Straus made another surprise announcement: the Andy Warhol Foundation would sell at Christie’s the estimated 20,000 pictures, prints, drawings, and photographs still remaining in Warhol’s original bequest until it has finally divested itself of most of the work by Andy Warhol it owns.7 Proceeds from these sales, the first of which took place in November 2012, will enable the foundation to increase its grants to museums and other organizations.8

Trying to explain those decisions, Wachs stated that the foundation’s priority was its “responsibility to Andy’s mission. Our money should be going to artists, not lawyers.” But why, in uncertain economic times and when most financial experts consider blue-chip artists like Warhol among the safest investments, has the foundation chosen this moment to sell such an enormous number of works?

For although it was always inevitable that the foundation’s supply of Warhols it could offer for sale would diminish until few if any were left, the number of works being offered for sale suggests that this would not have happened for some time. Even taking into consideration the cost of storing and curating the huge number of works the foundation owns and pays its sales agents to sell for them, its operating expenses have always been offset by the inexorable rise in prices for his work.

The Art Newspaper and The New York Times dutifully reported the story as it appeared in press releases issued by the Warhol Foundation and Christie’s. Neither publication later asked whether there is any connection between the closure of the authentication board in October 2011 and the announcement nine months later of the sale of the foundation’s material assets. But I believe there is a connection—in the form of another lawsuit that has had relatively little attention.

In April 2010, Philadelphia Indemnity, the company with whom the Andy Warhol Foundation had contracted to provide liability insurance, brought a lawsuit against the foundation. The insurance company refused to pay costs arising from allegations in Simon-Whelan’s lawsuit, which is mentioned on almost every page of their complaint, saying that, among a number of contractual violations, the foundation failed to notify them—as the foundation’s insurance policy required—of “any specific wrongful act” committed by one of the foundation’s members, including the publication of material “with knowledge of its falsity.” In response, the foundation countersued for full payment of its legal costs in that case—up to $10 million.

While litigation was in progress, lawyers for Philadelphia Indemnity were made aware of papers that Joe Simon-Whelan filed with the court on November 5, 2010, in his own suit against the foundation—including transcripts of witness testimony taken during the pre-trial hearings.9 These were placed in the public domain by Laura Swain, the judge in that suit, on February 15, 2011. They can be read by any member of the public at the United States Courthouse on Pearl Street.10

This is what lawyers for Philadelphia Indemnity could have learned from those documents.

2.

The Andy Warhol Art Foundation has always presented itself as operating independently from the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board. This made sense. The very fact that a dealer or museum bought a work directly from the foundation was considered a guarantee of authenticity. Paintings sold by the foundation were usually stamped on the reverse with a “PA” (i.e., painting) or a “PO” (i.e., portrait) number, as for example “PA81.014.” Such works normally did not need further authentication by the board.

But on some occasions, the authentication board did pass judgment on pictures owned by the foundation. When that happened, it was essential that the authentication board be seen to operate independently. Only then could the foundation sell the work as an authentic Warhol in good faith.

In reality, however, distinctions between the foundation and the authentication board are hard to detect. Joel Wachs is not only president of the foundation, but was also chairman of the authentication board with the power to appoint its members, although he does not take part in the process of authentication. The board had two full-time employees paid for by the foundation—Neil Printz and Sally King-Nero. They were assisted by a panel of three outside scholars and curators who were paid $2,000 per day plus travel and expenses.

Advertisement

The board met three times a year to pass judgment on the authenticity of all works submitted to it. Also in attendance at these meetings as a “consultant” to the board was Warhol’s former assistant Vincent Fremont (or rather, Vincent Fremont Enterprises, the only shareholder of which is Vincent Fremont), who until recently also worked for the foundation as its chief sales agent for paintings, sculpture, and drawings.

In that capacity Fremont was paid a commission of between 6 percent and 10 percent on all sales. According to Fremont himself, he “never missed a meeting” of the authentication board. When the foundation submitted works to the authentication board, Fremont was therefore in a position to help King-Nero and Printz declare to be genuine a work that, as the foundation’s chief salesman, he could then offer for sale.

Because the board’s meetings were held in secret, until recently it was impossible to know how the members reached their decisions. But the papers that have now been made public thanks to Judge Swain throw light on the board’s deliberations. They also provide documentary evidence that on several occasions the board authenticated works that it had already declared to be fakes. In one electrifying moment during his deposition, on July 7, 2010, Fremont admitted that on at least one occasion he sold as authentic Warhols paintings that the estate of Andy Warhol had confiscated from the owner on the grounds that they were not the work of Andy Warhol. He also admitted that the authentication board on which he sits decided that the same body of work had been created under what one member called false pretenses. What made the sales legitimate, he said, was that the authentication board later declared the paintings to be genuine after all.

I will make it clear here just how that happened. But first it should be explained that the estate consisted of tens of thousands of paintings and prints, most of them made at offsite factories from acetates, or plastic sheets, supplied by Warhol. One such factory is of particular relevance. Rupert Jasen Smith was Warhol’s main offsite printer from 1977 until 1987, responsible for creating thousands of Warhol’s paintings and prints. Smith’s factory and others like it invoiced Warhol Enterprises for their work and were paid for each authorized piece they created. But because Warhol never visited these factories the printers worked without supervision. Warhol therefore had no way of knowing who might be running off unauthorized prints or paintings in addition to the ones for which Warhol had paid him.11

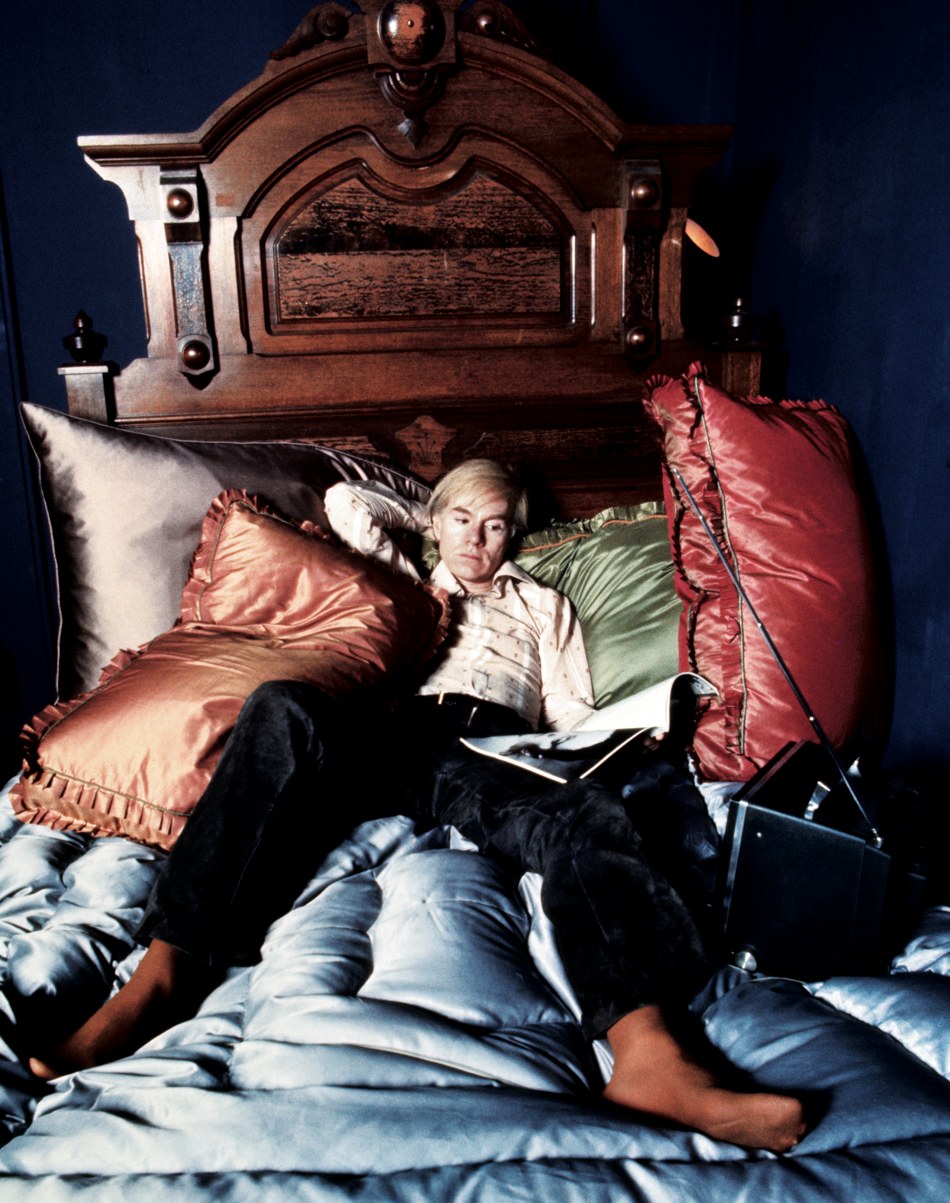

Steve Schapiro

Andy Warhol and his entourage (Henry Geldzahler and Edie Sedgwick at left; Gerard Malanga at far right), New York City, 1965. From Steve Schapiro: Then and Now, a collection of more than 170 of Schapiro’s photographs from his fifty-year career, most of which have never been seen before. The book includes an essay by Matthias Harder and is published by Hatje Cantz.

3.

The Warhol Foundation owns an undisclosed number of unauthorized prints. In some cases their status, as decreed by the authentication board, has fluctuated. At a meeting in November 1995, the board concluded that “if any print is out of the edition it will receive an Exhibit B letter of opinion [denying it is by Warhol]—with no exception.” The words “out of the edition” presumably mean that they do not belong to a group of prints—an “edition”—of which Warhol was aware. If Warhol was not aware of the prints that Smith and other printers produced, then those works are not by Warhol. But eleven years later, at a meeting held on July 19, 2006, the board reversed its earlier decision. Now describing the same unauthorized prints as “out of edition” and “outside the published edition,” the board still accorded them an “A” classification, that is, authentic works by Andy Warhol that the foundation was now in a position to sell. In doing so they opened up an area of confusion about what constitutes a genuine print by Warhol that needs further investigation beyond the scope of this article.

But for now I want to focus on the history of forty-four paintings made by Rupert Jasen Smith. Unlike the great majority of the prints, some of these were fraudulently signed with Warhol’s name by someone clumsily imitating his signature. As I shall show, the authentication board was fully aware that these signatures were false.

We do not know whether these paintings were made during Warhol’s lifetime or after his death in 1987. But when Smith himself died in 1989 they were in the printer’s estate. In a letter dated September 25, 1991, the Warhol estate asked Smith’s executor Fred Dorfman and heir Mark Smith to hand over the forty-four paintings that were then in Smith’s studio. The reason the estate gave for its request was that these paintings were not the work of Andy Warhol. The September 25 letter, which the foundation’s chief financial officer K.C. Maurer has said appears to be signed by Vincent Fremont, explained that “because of the similarity of the Paintings to authentic works by Andy Warhol, their releases might threaten the integrity of the art market and Andy Warhol’s reputation.” Dorfman brought the pictures, as requested, to the Warhol Estate personally. He did not receive compensation.

In that important letter of September 25, 1991, the representative of the estate of Andy Warhol wrote that as a result of an examination, “the Warhol Estate came to the opinion that the Paintings are not the work of Andy Warhol, and as provided in the letter agreement, a legend to this effect has been endorsed on the reverse side of each canvas.” The confiscated works were therefore stamped to reflect the estate’s judgment that they were not genuine. However, an estate stamp was different from the authentication board’s stamp, saying “DENIED,” which had been affixed, for example, to the back of Joe Simon-Whelan’s Warhol painting. Unlike the “DENIED” stamp in red ink that the authentication board impressed on the back of Simon-Whelan’s painting, the black ink of the estate stamp was not indelible and so could be removed.

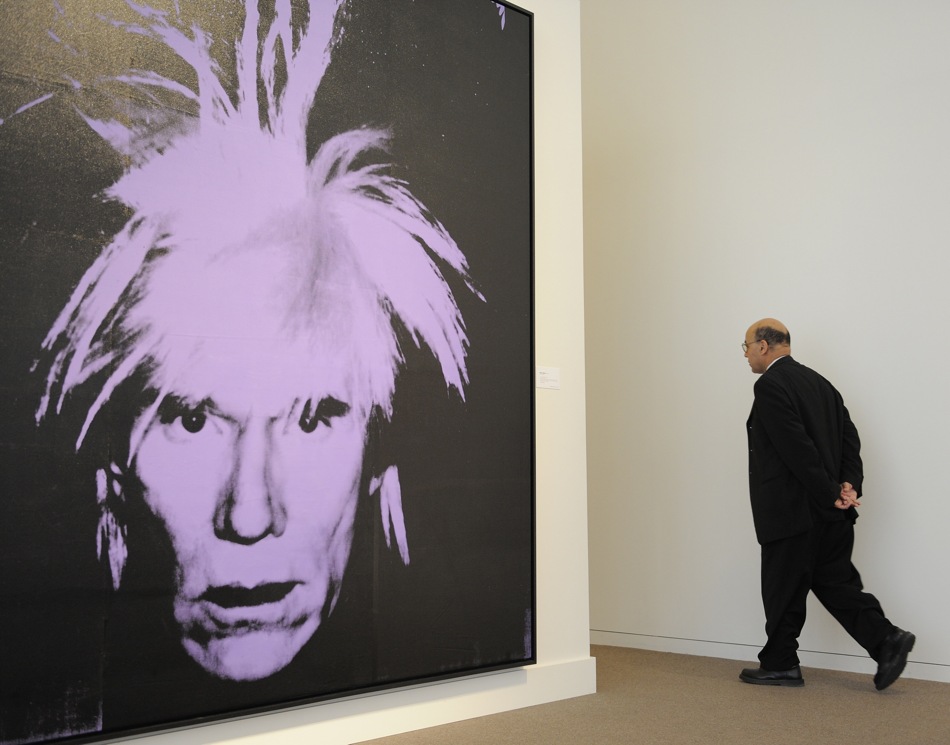

To be clear: the works in question were not relatively inexpensive prints but paintings on canvas, including such famous images as Warhol’s 1986 “Fright Wig” self-portrait, an image of a type similar to one Tom Ford sold at Sotheby’s with a full provenance in May 2010 for over $32 million.

After declaring in 1991 that the confiscated paintings were not the work of Andy Warhol, more than ten years passed, during which time Andy Warhol’s work became increasingly valuable. In his July 7, 2010, deposition in the suit brought by Simon-Whelan, Fremont explained what happened next. The more he looked at the works confiscated from Rupert Jasen Smith’s studio, he said, the more he came to feel that they resembled “other” (presumably real or at least authenticated) works already owned by the foundation. In his own words during his deposition: “There was less and less there that was problematic—with the exception of the signature…and some sizes of some of the work, but they became, to me, worthy of review.” By “review” he meant reexamination by the authentication board.

In due course Fremont proposed that the pictures be resubmitted for authentication. “I made a suggestion to the foundation maybe that these should be—you know, reviewed again, by an independent body—not by me, but by an independent body, being the art authentication board.” But the “independent body” he referred to is the one chaired by Wachs and whose meetings Fremont continued to attend as a consultant.

In June 2003 the authentication board therefore looked at these paintings again. The minutes for that meeting show it reached the conclusion that the paintings were “created under false pretenses [and] the circumstances under which these were made was inherently dishonest.” In the words of Neil Printz, the board refused to authenticate the works on the grounds, among others, that “some signatures are bad.”

The notes from the June 2003 meeting of the authentication board read in part:

Paintings: there is no clear edition [presumably a specific group of paintings of whose printing Warhol was aware], so that RJS [Rupert Jasen Smith] was making the paintings without his knowledge, how many does RJS make—should they be out in the world as Warhol’s—no they should not be. Conclusion: these paintings should receive a B letter of opinion [meaning they should be denied as inauthentic] or a studio of Rupert Jasen Smith letter [meaning the work was made by Rupert Jasen Smith, not by Andy Warhol].

The matter should have ended there. But the notes for that June 2003 meeting conclude with an extraordinary postscript: the issue of the authenticity of these paintings is to be “discussed again in October 2003 meeting.”

The result of the October 2003 meeting was that some of the paintings produced by Rupert Jasen Smith without Warhol’s knowledge were, after all, deemed to be authentic works made by Andy Warhol. In Fremont’s words, the paintings turned over by Dorfman, including those with bad signatures, “went through the normal process. Some were authenticated, some weren’t.”

In fact, those that weren’t authenticated at the October 2003 meeting were once again “held over” to be discussed at future meetings. Asked under oath whether the works that the board authenticated had been authorized by Warhol, however, Fremont replied, “I don’t know, factually.” Yet according to the board’s records, Neil Printz had told Fremont that in 1991 the estate “deemed” these paintings to be “inauthentic”; to have been “created under false pretenses”; and to have signatures that were “not good.”

It is still unclear how the authentication board reached its decision to sell an undisclosed number of these works. The minutes for that October 2003 meeting are missing. Despite a court order to hand over all relevant documents they are not among the transcripts of witness statements and other key documents filed with the court or made available during the pre-trial discovery.

In 2010, when the lawyer in Simon-Whelan’s original suit questioning Fremont asked whether he had ever sold work owned by the foundation that its own authentication board had authenticated, Fremont replied, “There’s only been the one occasion, which would be the Fred Dorfman paintings.” By “the Fred Dorfman paintings” he meant the works made by Rupert Jasen Smith that Dorfman handed over to the foundation in 1991.

We do not know which specific paintings Fremont sold, or to whom. Nor do we know whether Fremont told clients that he was not “factually” sure that the work he was selling was actually by Warhol, or whether he provided them with a full and accurate account of their history.

It will be interesting to see whether they will be included in forthcoming volumes of the foundation’s catalogue raisonné and how they will be described. Collectors may wish to note that, according to the submission documents, among the paintings that K.C. Maurer submitted to the board are Campbell’s Soup Boxes, Large Kiss, Jackie, Jackie 2, 1986 Last Supper, and Self Portraits. The process of submitting these works began in the autumn of 2002 and continued in February 2003. As we have seen, the status of the works was still being reviewed at the board meetings in June and October 2003. None of these images were included in the Christie’s sale on November 12, 2012.

A further question remains. Which employee of the foundation sent the paintings with phony signatures to the board for reexamination? At first Maurer denied under oath that she had submitted the works in question to the authentication board on behalf of the foundation. In fact, documents show that numerous works were submitted to the board under her name, including the forty-four works listed in the foundation’s inventory as known fakes that had been in the custody of the Warhol estate.

Despite being shown that evidence, Maurer said she did not recall having done this. Under oath, she said that perhaps someone else had submitted the pictures on her behalf, presumably by signing her signature to the form. Also under oath Maurer said that only two people from the foundation are authorized to submit works owned by the foundation to the authentication board. She is one. The other is Joel Wachs.

4.

If the board considered certain paintings to be genuine that—according to its own experts—were made under false pretenses and with fake signatures, what did it make of a painting that Warhol not only acknowledged as his own work, but also signed, dated, and inscribed during the 1960s? On February 24, 2003, the board met to consider Anthony d’Offay’s signed and inscribed Red Self Portrait. In the minutes of that meeting Fremont says that the signature, date, and dedication on that picture indicated that “Warhol is acknowledging the painting.” In response, Neil Printz says that he and King-Nero have seen hundreds of works by Warhol and that this one was made “outside the studio.”

No one else in the February 24 meeting challenges this statement, and yet all those who attended the meeting would have known well that the majority of Warhol works were made in off-site studios such as Rupert Smith’s. The fact that d’Offay’s Red Self Portrait was an early instance of this working method should not in itself have been a reason to deny its authenticity.

The brief, fragmentary written notations of what was said at the meeting do not always identify the speaker, but they continue with the words “good signature, why wouldn’t it be a Warhol[?].” But Printz (who is identified by his initials) prevails, ending the discussion by declaring that d’Offay’s painting Red Self Portrait should be given the status of a “Warhol-related object” (i.e., denied) because “it admits there is serious discrimination going on.”

The meaning of that phrase is unclear, but the use of the word “admits” seems to suggest at least two possible interpretations. One is that Printz wants the board to deny the authenticity of d’Offay’s picture because not to do so would be to admit that there was serious discrimination going on in favor of a powerful dealer at the expense of small-fry owners of pictures from the same series like Simon-Whelan. The other possibility is that he wants the board to demonstrate that they seriously discriminate between work Warhol painted by hand and work that was created outside his studio. Yet neither explain why a signed, dated, and inscribed picture that Warhol included in his first catalogue raisonné is not a Warhol.

5.

After seven months of litigation, a “stipulation of discontinuance” of the dispute between the Warhol Foundation and its insurers Philadelphia Indemnity was filed in the New York Supreme Court. In other words both parties settled out of court. Though the terms of the settlement are still unknown—and as we have seen, the Warhol Foundation has mounted a countersuit against Philadelphia Indemnity for full payments of its legal costs—the date of the out-of-court settlement is not: the case was settled on October 25, 2010. That is about a year before Michael Straus announced the closure of the board on October 19, 2011.

What might appear to be a simple contractual dispute goes right to the heart of the issues discussed in this article. At the very least, we now know that the supposedly independent authentication board worked closely with the foundation. The documents I have cited also raise the question of whether some of the decisions the board made about the authenticity of artworks were not based on disinterested scholarship, as the insurers may have believed, but were made for other reasons such as financial gain or the perceived need to save face.

Meanwhile, the countersuit between the Warhol Foundation and its insurance company has suddenly reignited. In December 2012, Judge Peter Sherwood denied the insurer’s request for a summary judgment to dismiss the Warhol Foundation’s complaint. Though some media outlets, such as ARTINFO, have reported this ruling as a victory for the Warhol Foundation, in fact the judge allowed merely that the case may proceed.

So, as I write this, the case will go to trial. And when that happens, attorneys for the insurers have stated that they are ready “with other, unspecified defenses to fight [its] claims.” I do not know what these defenses are, but if they are linked to the documents cited in this article, then the coming year may prove to be the most difficult yet for the Warhol Foundation.

This Issue

June 20, 2013

Cool, Yet Warm

Facing the Real Gun Problem

-

1

Notes of December 7, 1994, meeting of the directors of the Andy Warhol Foundation, cited in Joe Simon-Whelan’s letter to the court, November 5, 2010, exhibit 36. ↩

-

2

To cite one widely reported recent example, the board authenticated a series of Brillo box sculptures that were shown to have been faked after Warhol’s death. See Adrian Levy and Cathy Scott-Clark, “Warhol’s Box of Tricks,” The Guardian, August 20, 2010. ↩

-

3

See Jason Kaufman, “Challenge to the Andy Warhol Authentication Board,” The Art Newspaper, October 2003, quoting Ronald D. Spencer, lawyer and spokesman for the board: “The board does not explain its decisions because to do so would provide ‘a roadmap for forgers.’” It is worth stressing, however, that these procedures are not typical of other art authentication boards. See the letter signed by Sarah Whitfield on behalf of the Comité René Magritte, Francis Bacon Authentication Committee, and Arshile Gorky Foundation, “What Is a Warhol? An Exchange,” The New York Review, December 17, 2009. ↩

-

4

See Richard Dorment, “What Is an Andy Warhol?” The New York Review, October 22, 2009, and “What Andy Warhol Did,” The New York Review, April 7, 2011, with subsequent exchanges and letters by, among others, Joel Wachs, Rainer Crone, Richard Ekstract, Reva Wolf, and Sarah Whitfield published on November 19, 2009, December 17, 2009, February 25, 2010, June 9, 2011, and August 18, 2011 (both in print and in longer versions online). ↩

-

5

See Andrew Johnson, “Warhol Wars,” The Independent, July 11, 2010. ↩

-

6

See Kelly Crow, “Is That Warhol a Fake? Even His Foundation Isn’t Sure,” The Wall Street Journal, October 20, 2011. Though the board would continue to process works of art already submitted to it, Straus said it would no longer accept new work submitted for authentication. The board is now closed. ↩

-

7

“Warhol Foundation Seals Long-Term Deal with Christie’s.” The auction house also started holding online auctions in February 2013, and is negotiating private sales. ↩

-

8

All future volumes of the catalogue raisonné will be written by former authentication board members Neil Printz and Sally King-Nero. Their inclusion of an artwork in their catalogue raisonné will amount to a judgment as to its authenticity. Since both are still employees of the foundation, their catalog will serve a function much like the former authentication board but without a panel of outside advisers who (in theory) monitored their activities. Once the foundation has divested itself of all of Warhol’s work, Printz and King-Nero will no longer be in a position to pass judgment on works the foundation owns and sells. But they apparently will continue to make judgments when they come to consider the status of the artworks the foundation is now selling at Christie’s. ↩

-

9

Addison Thompson’s e-mail to the author, November 9, 2011, reads as follows: “Addison Thompson, Photographer, motivated by his own dispute with the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board and Andy Warhol Foundation over their denial of Mr. Thompson’s early Andy Warhol Self-Portrait drawing, sent copies of Joe Simon’s letter to Judge Peck,” magistrate in the case; a duplicate letter was sent to Judge Swain dated November 5, 2010, to attorneys Stephen Marcellino and Richard Reiter, lawyers for the Philadelphia Indemnity Insurance Company in their lawsuit against the Warhol Foundation.

Subsequently, Thompson phoned and spoke to Reiter and described in detail the alleged misconduct by the Warhol Foundation contained on pages 9–10 of Simon-Whelan’s letter of November 5, 2010. That letter cited testimony, under oath, from Vincent Fremont, who confiscated important Warhol works from the Rupert Smith estate in 1991, because of their questionable signatures and authenticity, only to have the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board authenticate many of them in 2002. ↩ -

10

The sources for all the facts in this article are contained in the exhibits made available at the United States Courthouse in Pearl Street by Judge Swain, who heard arguments against the Warhol Foundation by Joe Simon-Whelan, and by Judge Peter Sherwood in New York State Supreme Court, who is hearing the case brought by the Warhol Foundation against Philadelphia Indemnity Insurers. Documents from the Warhol Foundation’s suit against Philadelphia Indemnity can be accessed free of charge at the New York State United Court System website.

As a guide for readers to some of the most important evidence I use, the following may be helpful:1) Legal tactics used by the Warhol foundation’s lawyer. Joe Simon-Whelan’s letter to the court November 5, 2010 and exhibit 37 including July 21, 2010 letter to the court.

↩

2) Confiscation of works of art produced by Rupert Jasen Smith’s printing factory, exhibits 16, 17.

3) K.C. Maurer’s deposition, exhibits 16, 18.

4) Foundation meeting notes, exhibit 16.

5) Authentication board meeting notes, exhibits 16a and 16b.

6) Works submitted by the foundation, exhibit 16.

7) Transcript of Vincent Fremont’s deposition regarding the authentication of fake works, exhibit 17.

8) Prints, exhibit 20. -

11

So far authenticity is concerned, the question of pirate or unauthorized prints and bronzes is a gray area. A comparable situation arises when Sotheby’s sells bronze casts that were made from models provided by nineteenth-century sculptors such as Barye and Carpeaux. In many cases there may be no guarantee that the sculptor ever saw or touched the cast, but these are sold as authentic works, with the price largely determined by the quality of the cast.

When a bronze is sold with a bill of sale, a known provenance, or when it can be shown that the artist personally intervened in its creation (for example in the chasing or patination of the cast), these factors normally affect the price. The difference with the Warhol authentication board’s authentication of prints made without Warhol’s permission is that the board was well aware of who made these works and under what circumstances. ↩