1.

In the United States, as in many other countries, obesity is a serious problem. New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg wants to do something about it. Influenced by many experts, he believes that soda is a contributing factor to increasing obesity rates and that large portion sizes are making the problem worse. In 2012, he proposed to ban the sale of sweetened drinks in containers larger than sixteen ounces at restaurants, delis, theaters, stadiums, and food courts. The New York City Board of Health approved the ban.

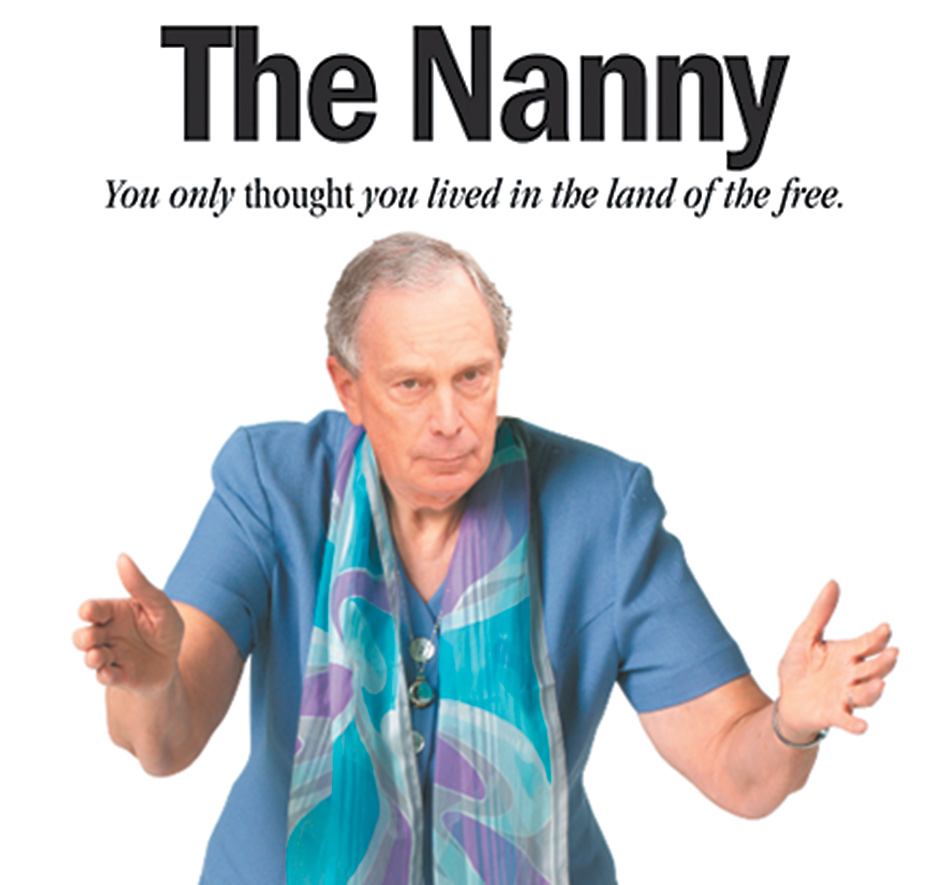

Many people were outraged by what they saw as an egregious illustration of the nanny state in action. Why shouldn’t people be allowed to choose a large bottle of Coca-Cola? The Center for Consumer Freedom responded with a vivid advertisement, depicting Mayor Bloomberg in a (scary) nanny outfit.

But self-interested industries were not the only source of ridicule. Jon Stewart is a comedian, but he was hardly amused. A representative remark from one of his commentaries: “No!…I love this idea you have of banning sodas larger than 16 ounces. It combines the draconian government overreach people love with the probable lack of results they expect.”

Many Americans abhor paternalism. They think that people should be able to go their own way, even if they end up in a ditch. When they run risks, even foolish ones, it isn’t anybody’s business that they do. In this respect, a significant strand in American culture appears to endorse the central argument of John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty. In his great essay, Mill insisted that as a general rule, government cannot legitimately coerce people if its only goal is to protect people from themselves. Mill contended that

the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or mental, is not a sufficient warrant. He cannot rightfully be compelled to do or forbear because it will be better for him to do so, because it will make him happier, because, in the opinion of others, to do so would be wise, or even right.1

A lot of Americans agree. In recent decades, intense controversies have erupted over apparently sensible (and lifesaving) laws requiring people to buckle their seatbelts. When states require motorcyclists to wear helmets, numerous people object. The United States is facing a series of serious disputes about the boundaries of paternalism. The most obvious example is the “individual mandate” in the Affordable Care Act, upheld by the Supreme Court by a 5–4 vote, but still opposed by many critics, who seek to portray it as a form of unacceptable paternalism.2 There are related controversies over anti-smoking initiatives and the “food police,” allegedly responsible for recent efforts to reduce the risks associated with obesity and unhealthy eating, including nutrition guidelines for school lunches.

Mill offered a number of independent justifications for his famous harm principle, but one of his most important claims is that individuals are in the best position to know what is good for them. In Mill’s view, the problem with outsiders, including government officials, is that they lack the necessary information. Mill insists that the individual “is the person most interested in his own well-being,” and the “ordinary man or woman has means of knowledge immeasurably surpassing those that can be possessed by any one else.”

When society seeks to overrule the individual’s judgment, Mill wrote, it does so on the basis of “general presumptions,” and these “may be altogether wrong, and even if right, are as likely as not to be misapplied to individual cases.” If the goal is to ensure that people’s lives go well, Mill contends that the best solution is for public officials to allow people to find their own path. Here, then, is an enduring argument, instrumental in character, on behalf of free markets and free choice in countless situations, including those in which human beings choose to run risks that may not turn out so well.

2.

Mill’s claim has a great deal of intuitive appeal. But is it right? That is largely an empirical question, and it cannot be adequately answered by introspection and intuition. In recent decades, some of the most important research in social science, coming from psychologists and behavioral economists, has been trying to answer it. That research is having a significant influence on public officials throughout the world. Many believe that behavioral findings are cutting away at some of the foundations of Mill’s harm principle, because they show that people make a lot of mistakes, and that those mistakes can prove extremely damaging.

Advertisement

For example, many of us show “present bias”: we tend to focus on today and neglect tomorrow.3 For some people, the future is a foreign country, populated by strangers.4 Many of us procrastinate and fail to take steps that would impose small short-term costs but produce large long-term gains. People may, for example, delay enrolling in a retirement plan, starting to diet or exercise, ceasing to smoke, going to the doctor, or using some valuable, cost-saving technology. Present bias can ensure serious long-term harm, including not merely economic losses but illness and premature death as well.

People also have a lot of trouble dealing with probability. In some of the most influential work in the last half-century of social science, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky showed that in assessing probabilities, human beings tend to use mental shortcuts, or “heuristics,” that generally work well, but that can also get us into trouble.5 An example is the “availability heuristic.” When people use it, their judgments about probability—of a terrorist attack, an environmental disaster, a hurricane, a crime—are affected by whether a recent event comes readily to mind. If an event is cognitively “available”—for example, if people have recently suffered damage from a hurricane—they might well overestimate the risk. If they can recall few or no examples of harm, they might well underestimate the risk.

A great deal of research finds that most people are unrealistically optimistic, in the sense that their own predictions about their behavior and their prospects are skewed in the optimistic direction.6 In one study, over 80 percent of drivers were found to believe that they were safer and more skillful than the median driver. Many smokers have an accurate sense of the statistical risks, but some smokers have been found to believe that they personally are less likely to face lung cancer and heart disease than the average nonsmoker.7 Optimism is far from the worst of human characteristics, but if people are unrealistically optimistic, they may decline to take sensible precautions against real risks. Contrary to Mill, outsiders may be in a much better position to know the probabilities than people who are making choices for themselves.

Emphasizing these and related behavioral findings, many people have been arguing for a new form of paternalism, one that preserves freedom of choice, but that also steers citizens in directions that will make their lives go better by their own lights.8 (Full disclosure: the behavioral economist Richard Thaler and I have argued on behalf of what we call libertarian paternalism, known less formally as “nudges.”9) For example, cell phones, computers, privacy agreements, mortgages, and rental car contracts come with default rules that specify what happens if people do nothing at all to protect themselves. Default rules are a classic nudge, and they matter because doing nothing is exactly what people will often do. Many employees have not signed up for 401(k) plans, even when it seems clearly in their interest to do so. A promising response, successfully increasing participation and strongly promoted by President Obama, is to establish a default rule in favor of enrollment, so that employees will benefit from retirement plans unless they opt out.10 In many situations, default rates have large effects on outcomes, indeed larger than significant economic incentives.11

Default rules are merely one kind of “choice architecture,” a phrase that may refer to the design of grocery stores, for example, so that the fresh vegetables are prominent; the order in which items are listed on a restaurant menu; visible official warnings; public education campaigns; the layout of websites; and a range of other influences on people’s choices. Such examples suggest that mildly paternalistic approaches can use choice architecture in order to improve outcomes for large numbers of people without forcing anyone to do anything.

In the United States, behavioral findings have played an unmistakable part in recent regulations involving retirement savings, fuel economy, energy efficiency, environmental protection, health care, and obesity.12 In the United Kingdom, Prime Minister David Cameron has created a Behavioural Insights Team, sometimes known as the Nudge Unit, with the specific goal of incorporating an understanding of human behavior into policy initiatives.13 In short, behavioral economics is having a large impact all over the world, and the emphasis on human error is raising legitimate questions about the uses and limits of paternalism.

3.

Until now, we have lacked a serious philosophical discussion of whether and how recent behavioral findings undermine Mill’s harm principle and thus open the way toward paternalism. Sarah Conly’s illuminating book Against Autonomy provides such a discussion. Her starting point is that in light of the recent findings, we should be able to agree that Mill was quite wrong about the competence of human beings as choosers. “We are too fat, we are too much in debt, and we save too little for the future.” With that claim in mind, Conly insists that coercion should not be ruled out of bounds. She wants to go far beyond nudges. In her view, the appropriate government response to human errors depends not on high-level abstractions about the value of choice, but on pragmatic judgments about the costs and benefits of paternalistic interventions. Even when there is only harm to self, she thinks that government may and indeed must act paternalistically so long as the benefits justify the costs.

Advertisement

Conly is quite aware that her view runs up against widespread intuitions and commitments. For many people, a benefit may consist precisely in their ability to choose freely even if the outcome is disappointing. She responds that autonomy is “not valuable enough to offset what we lose by leaving people to their own autonomous choices.” Conly is aware that people often prefer to choose freely and may be exceedingly frustrated if government overrides their choices. If a paternalistic intervention would cause frustration, it is imposing a cost, and that cost must count in the overall calculus. But Conly insists that people’s frustration is merely one consideration among many. If a paternalistic intervention can prevent long-term harm—for example, by eliminating risks of premature death—it might well be justified even if people are keenly frustrated by it.

To Mill’s claim that individuals are uniquely well situated to know what is best for them, Conly objects that Mill failed to make a critical distinction between means and ends. True, people may know what their ends are, but sometimes they go wrong when they choose how to get them. Most people want to be healthy and to live long lives. If people are gaining a lot of weight, and hence jeopardizing their health, Conly supports paternalism—for example, she favors reducing portion size for many popular foods, on the theory that large, fattening servings can undermine people’s own goals. In her words, paternalism is justified when

the person left to choose freely may choose poorly, in the sense that his choice will not get him what he wants in the long run, and is chosen solely because of errors in instrumental reasoning.

Because of her focus on the means to the ends people want, Conly’s preferred form of paternalism is far more modest than imaginable alternatives.

At the same time, Conly insists that mandates and bans can be much more effective than mere nudges. If the benefits justify the costs, she is willing to eliminate freedom of choice, not to prevent people from obtaining their own goals but to ensure that they do so. Following a long line of liberal thinking, and in a way that responds directly to potential objections, Conly emphatically rejects “perfectionism,” understood as the view that people should be required to live lives that the government believes to be best or most worthwhile.

Because hers is a paternalism of means rather than ends, she would not authorize government to stamp out sin (as, for example, by forbidding certain forms of sexual behavior) or otherwise direct people to follow official views about what a good life entails. She wants government to act to overcome cognitive errors while respecting people’s judgments about their own needs, goals, and values.

For coercive paternalism to be justified, Conly contends that four criteria must be met. First, the activity that paternalists seek to prevent must genuinely be opposed to people’s long-term ends as judged by people themselves. If people really love collecting comic books, stamps, or license plates, there is no occasion to intervene.

Second, coercive measures must be effective rather than futile. Prohibition didn’t work, and officials shouldn’t adopt strategies that fail. Third, the benefits must exceed the costs. To know whether they do, would-be paternalists must assess both material and psychological benefits and costs (including not only the frustration experienced by those who lose the power to choose but also the losses experienced by those who are coerced into something bad for them). Fourth, the measure in question must be more effective than the reasonable alternatives. If an educational campaign would have the benefits of a prohibition without the costs, then Conly favors the educational campaign.

Applying these criteria, Conly thinks that New York’s ban on trans fats is an excellent example of justifiable coercion. On the basis of the evidence as she understands it, the ban has been effective in conferring significant public health benefits, and those benefits greatly exceed its costs. Focused on the problem of obesity, Conly invokes similar points in support of regulations designed to reduce portion sizes.

She is far more ambivalent about Mayor Bloomberg’s effort to convince the US Department of Agriculture to authorize a ban on the use of food stamps to buy soda. She is not convinced that the health benefits would be significant, and she emphasizes that people really do enjoy drinking soda.

Conly’s most controversial claim is that because the health risks of smoking are so serious, the government should ban it. She is aware that many people like to smoke, that a ban could create black markets, and that both of these points count against a ban. But she concludes that education, warnings, and other nudges are insufficiently effective, and that a flat prohibition is likely to be justified by careful consideration of both benefits and costs, including the costs to the public of treating lung cancer and other consequences of smoking.

4.

Conly’s argument is careful, provocative, and novel, and it is a fundamental challenge to Mill and the many people who follow him. But it is in less severe tension with current practices than it might seem. A degree of paternalism is built into the workings of the modern regulatory state. Under long-standing law, you have to obtain a prescription to get a wide range of medicines. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration forbids people from working in unsafe conditions even if they would willingly do so. Both the Food and Drug Administration and the Department of Agriculture regulate food safety, and you are not allowed to buy foods that they ban, even if you are convinced that they are perfectly safe. One of Conly’s points is that the government already makes many decisions for us, and she believes that is just fine.

A natural objection is that autonomy is an end in itself and not merely a means. On this view, people should be entitled to choose as they like, even if they end up choosing poorly. In a free society, people must be allowed to make their own mistakes, and to the extent possible learn from them, rather than facing correction and punishment from bureaucratic meddlers. Conly responds that when government makes (some) decisions for us, we gain not only in personal welfare but also in autonomy, if only because our time is freed up to deal with what most concerns us:

It is very important to my continued existence that my car be safe, but I do not want to have to come up with a reasonable set of auto safety standards…. If the government were to do the research and ascertain that trans-fats are bad for my health and then remove trans-fats from my diet options, I’d be grateful.

She adds that if we are genuinely promoting people’s ends, and allowing paternalism only with respect to means, the claims of autonomy are sufficiently respected. As we shall shortly see, however, this suggestion raises questions of its own.

Conly is right to insist that no democratic government can or should live entirely within Mill’s strictures. But in my view, she underestimates the possibility that once all benefits and all costs are considered, we will generally be drawn to approaches that preserve freedom of choice. One reason involves the bluntness of coercive paternalism and the sheer diversity of people’s tastes and situations. Some of us care a great deal about the future, while others focus intensely on today and tomorrow. This difference may make perfect sense in light not of some bias toward the present, but of people’s different economic situations, ages, and valuations. Some people eat a lot more than others, and the reason may not be an absence of willpower or a neglect of long-term goals, but sheer enjoyment of food. Our ends are hardly limited to longevity and health; our short-term goals are a large part of what makes life worth living.

Conly favors a paternalism of means, but the line between means and ends can be fuzzy, and there is a risk that well-motivated efforts to promote people’s ends will end up mischaracterizing them. Sure, some of our decisions fail to promote our ends; if we neglect to rebalance our retirement accounts, we may end up with less money than we want. But some people who often rebalance their accounts end up doing poorly. In some cases, moreover, means-focused paternalists may be badly mistaken about people’s goals. Those who delay dieting may not be failing to promote their ends; they might simply care more about good meals than about losing weight.

Freedom of choice is an important safeguard against the potential mistakes of even the most well-motivated officials. Conly heavily depends on cost-benefit analysis, which is mandated by President Obama’s important executive order on federal regulation.14 It is also a crucial means of disciplining the regulatory process.15 But the same executive order emphasizes that government agencies must identify and consider approaches that “maintain flexibility and freedom of choice for the public.” Officials may well be subject to the same kinds of errors that concern Conly in the first place. If we embrace cost-benefit analysis, we might be inclined to favor freedom of choice as a way of promoting private learning and reflection, avoiding unjustified costs, and (perhaps more important) providing a safety valve in the event of official errors.

Conly is quite aware of the many difficulties that would be associated with efforts to prohibit the manufacture and sale of alcohol and cigarettes, but here the problems seem to me more significant than she allows. True, smoking produces extremely serious public health problems—over 400,000 deaths annually—and it is important to take further steps to reduce those problems.16 But any ban would raise exceedingly serious difficulties, not least because it would be hard to enforce. A full analysis would have to consider such difficulties, as well as the claims of free choice. Black markets in cigarettes are not exactly what the United States most needs now.

Notwithstanding these objections, Conly convincingly argues that behavioral findings raise significant questions about Mill’s harm principle. When people are imposing serious risks on themselves, it is not enough to celebrate freedom of choice and ignore the consequences. What is needed is a better understanding of the causes and magnitude of those risks, and a careful assessment of what kind of response would do more good than harm.

This Issue

March 7, 2013

Warrior Petraeus

The Way They Live Now

-

1

It is important to emphasize that Mill was concerned with coercion of all kinds, including those forms that come from the private sector and from social norms. ↩

-

2

To be sure, the individual mandate can be, and has been, powerfully defended on nonpaternalistic grounds; above all, it should be understood as an effort to overcome a free-rider problem that exists when people do not obtain health insurance (but are nonetheless subsidized in the event that they need medical help). ↩

-

3

See, for example, Shane Frederick et al., “Time Discounting and Time Preference: A Critical Review,” Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 40, No. 2 (2002), p. 351; Stephan Meier and Charles Sprenger, “Present-Biased Preferences and Credit Card Borrowing,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Vol. 2, No. 1 (2010), p. 193; Hal E. Hershfield et al., “Increasing Saving Behavior through Age-Progressed Renderings of the Future Self,” Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 48 (2011), p. S23. ↩

-

4

For neurological evidence, see Jason P. Mitchell et al., “Medial Prefrontal Cortex Predicts Intertemporal Choice,” Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, Vol. 23 (2010), pp. 1, 6. ↩

-

5

Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, “Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases,” Science, Vol. 185, No. 4157 (1974), p. 1124. Kahneman summarizes this work in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011). ↩

-

6

See generally Tali Sharot, The Optimism Bias (Pantheon, 2011). ↩

-

7

See Paul Slovic, “Do Adolescent Smokers Know the Risks?,” Duke Law Journal, Vol. 47, No. 6 (1998), pp. 1133, 1136–1137. ↩

-

8

See Colin Camerer et al., “Regulation for Conservatives: Behavioral Economics and the Case for ‘Asymmetric Paternalism,’” University of Pennsylvania Law Review, Vol. 151 (2003), p. 1211; George Loewenstein et al., “Asymmetric Paternalism to Improve Health Behaviors,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 298, No. 4 (2007), p. 2415. ↩

-

9

Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein, Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness (Yale University Press, 2008). ↩

-

10

See President Barack Obama, weekly address (September 5, 2009), announcing initiatives to increase participation in IRAs and match retirement savings. ↩

-

11

See Raj Chetty et al., “Active vs. Passive Decisions and Crowd Out in Retirement Savings Accounts: Evidence from Denmark” (December 2012), available at obs.rc.fas.harvard.edu/chetty/crowdout.pdf; Eric J. Johnson and Daniel G. Goldstein, “Decisions by Default,” in The Behavorial Foundations of Public Policy, edited by Eldar Shafir (Princeton University Press, 2012), p. 417. ↩

-

12

A detailed account appears in Cass R. Sunstein, Simpler: The Future of Government (forthcoming 2013); see also Cass R. Sunstein, “Empirically Informed Regulation,” University of Chicago Law Review, Vol. 78 (2011), p. 1349. ↩

-

13

The official website states that its “work draws on insights from the growing body of academic research in the fields of behavioural economics and psychology which show how often subtle changes to the way in which decisions are framed can have big impacts on how people respond to them.” See The Behavioral Insights Team, Cabinet Office, www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/behavioural-insights-team. ↩

-

14

Executive Order 13,563, Federal Register, Vol. 76, No. 24 (January 18, 2011), available at www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR- 2011-01-21/pdf/2011-1385.pdf. ↩

-

15

See Sunstein, Simpler; Cass R. Sunstein, “The Real World of Cost-Benefit Analysis: Thirty-Six Questions (and Almost as Many Answers)” (2013), available at papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm ?abstract_id=2199112. ↩

-

16

The graphic health warnings, required by the Food and Drug Administration, are one example; they are encountering serious challenges on First Amendment grounds. See R.J. Reynolds v. FDA, 696 F.3d 1205 (DC Cir. 2012). ↩