As recently as five years ago, American corrections officials almost uniformly denied that rape in prison was a widespread problem. When we at Just Detention International—an organization aimed at preventing the sexual abuse of inmates—recounted stories of people we knew who had been raped in prison, we were told either that these men and women were exceptional cases, or simply that they were liars. But all this has changed.

What we have now that we didn’t then is good data. The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), an agency within the Justice Department, has conducted a series of studies of the problem based on anonymous surveys that, between them, have reached hundreds of thousands of inmates. Those who agreed to take the surveys, without being informed in advance of the subject, spent an average of thirty-five minutes responding to questions on a computer touchscreen, with synchronized audio instructions given through headsets. The officials in charge either positioned themselves so they couldn’t see the computer screens or left the room.

The consistency of the findings from these surveys is overwhelming. The same factors that put inmates at risk of sexual abuse show up again and again, as do the same patterns of abuse involving race and gender, inmates and guards. Prison officials used to say that inmates were fabricating their claims in order to cause trouble. But then why, for example, do whites keep reporting higher levels of inmate-on-inmate sexual abuse than blacks? Is there some cultural difference causing white inmates to invent more experiences of abuse (or else causing blacks to hide what they are suffering)? If so, then why do blacks keep reporting having been sexually abused by their guards at higher rates than whites?1 The more closely one looks at these studies, the more persuasive their findings become. Very few corrections professionals now publicly dispute them.

The BJS has just released a third edition of its National Inmate Survey (NIS), which covers prisons and jails, and a second edition of its National Survey of Youth in Custody (NSYC). These studies confirm some of the most important findings from earlier surveys—among others, the still poorly understood fact that an extraordinary number of female inmates and guards commit sexual violence. They also reveal new aspects of a variety of problems, including (1) the appalling (though, from state to state, dramatically uneven) prevalence of sexual misconduct by staff members in juvenile detention facilities; (2) the enormous and disproportionate number of mentally ill inmates who are abused sexually; and (3) the frequent occurrence of sexual assault in military detention facilities.

According to the latest surveys, in 2011 and 2012, 3.2 percent of all people in jail, 4.0 percent of state and federal prisoners, and 9.5 percent of those held in juvenile detention reported having been sexually abused in their current facility during the preceding year.2 (Jails, which are usually run by county governments, typically hold people who have recently been arrested and are awaiting trial or release, or else serving sentences of less than a year; prisons are for those serving longer sentences.) The rate of abuse in prisons is slightly lower than has been reported in previous years, but the difference is too small to be statistically significant. For those in jail, the number has not shifted at all. The rate of abuse in state-run juvenile facilities has declined significantly since the 2008–2009 youth survey, in which 12.6 percent of juveniles reported sexual victimization. However, this finding doesn’t have much impact on the total number of people victimized since many fewer are held in juvenile detention than in prisons and jails.

Allen J. Beck, the senior BJS statistician who has been the lead author on all of these studies, tells us the new findings indicate that nearly 200,000 people were sexually abused in American detention facilities in 2011. Although that is fewer than the 209,400 inmates who, in the Justice Department’s estimation, were sexually abused in 2008, the decline has less to do with falling rates of abuse than with a decrease in the number of people going to prison and jail. In the twelve-month period ending midyear 2008, there were 13.6 million admissions to local jails; by midyear 2011, the number had fallen to 11.8 million. Similarly, prison admissions fell from 738,649 to 668,800.

The new studies confirm previous findings that most of those who commit sexual abuse in detention are corrections staff, not inmates. That is true in all types of detention facilities, but especially in juvenile facilities. The new studies also confirm that most victims are abused repeatedly during the course of a year. In juvenile facilities, victims of sexual misconduct by staff members were more likely to report eleven or more instances of abuse than a single, isolated occurrence. By far the two biggest risk factors for sexual abuse in all kinds of detention facilities are being “non-heterosexual,” as the BJS puts it, and having a history of sexual victimization that predates the inmate’s current incarceration.

Advertisement

As in previous studies, the rates of inmate-on-inmate sexual abuse reported by women were dramatically higher than the corresponding rates reported by men: among prisoners, 6.9 percent versus 1.7 percent. Men, on the other hand, reported higher rates than women of sexual misconduct by staff members (most of which is committed by staff of the opposite sex),3 and in juvenile detention, boys reported much higher rates of abuse by staff than girls did—most, again, committed by women.

In our experience, many people do not take sexual abuse committed by women as seriously as abuse committed by men. That includes many corrections officers. We have often heard staff members in women’s facilities refer dismissively to “cat fights” among the inmates and to the tendency of female inmates to replicate “family structures” inside prison. (In one such structure, for example, a woman assumes the role of “protective husband” in return for sexual favors.) But if such family structures involve sexual abuse, then this is a serious human rights issue. Rape by women is just as much of a violation as rape by men, and corrections authorities must start treating it accordingly.

The new National Inmate Survey included a group of inmates whom the BJS had previously been unable to question: sixteen- and seventeen-year-olds being held in adult prisons and jails.4 Some observers have worried that, because juveniles often lack the emotional maturity and street smarts that prison life can demand, they would be especially vulnerable to sexual victimization in adult facilities. Indeed, 4.5 percent of juveniles in prison and 4.7 percent of those in jail reported such victimization—rates that ought to be considered disastrously high. But although these were higher than the rates of sexual abuse reported by adult inmates, the difference was not statistically significant. Moreover, the new National Survey of Youth in Custody found that minors held in juvenile detention suffered sexual abuse at twice the rate of their peers in adult facilities.

Why are juvenile detainees so much safer in adult jails and prisons than in facilities intended for youth? One likely answer is that staff in adult facilities usually recognize the particular vulnerability of the minors in their care and make special efforts to protect them—housing them separately from adults (though often in the torturous conditions of long-term solitary confinement) and strictly limiting any interaction between incarcerated adults and minors.5 More starkly, as we will see, an extreme unprofessionalism has been allowed to persist among juvenile corrections staff in many states, to a degree that is rare in adult facilities.

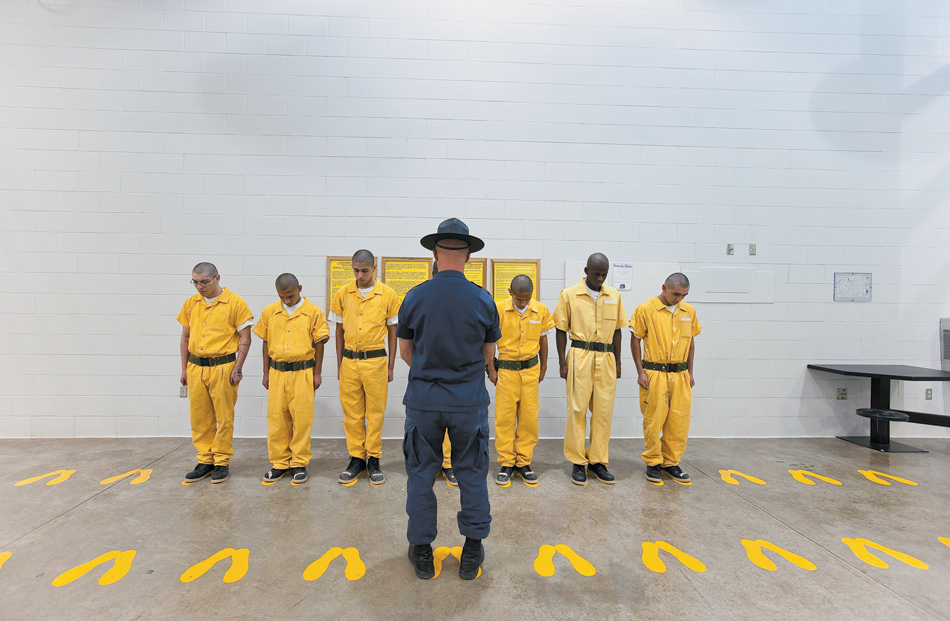

Juvenile detention facilities are supposed to offer opportunities for education, therapy, and rehabilitation that adult prisons and jails typically lack. In reality, though, many juvenile facilities have been more likely to traumatize the youth they confine than to help them; more likely to convert them into hardened career criminals than to steer them away from crime. But this may now be starting to change. Largely inspired by a model first developed in Missouri, many states have been reforming their juvenile corrections systems in recent years: locking kids up for shorter stretches of time in smaller facilities closer to the communities they come from, and strengthening their emphasis on therapy and rehabilitation. These changes are consistent with the BJS’s explanation for the decreasing rate of sexual abuse in juvenile detention since 2008–2009. As the new youth study reports, “declines in sexual victimization rates were linked to fewer youth held in large facilities, a drop in average exposure time, and rising positive views of facility staff and fairness.”6

That said, some states have evidently pursued reform more enthusiastically and intelligently than others, or, at any rate, more successfully. Young people in twenty-six juvenile facilities surveyed by the new NSYC reported no sexual abuse whatever. Of the fourteen largest of these, twelve were in Colorado, Kentucky, Missouri, or Oregon.7 On the other hand, nine of the thirteen worst-performing facilities were in Georgia, Ohio, or South Carolina—including the three very worst, where, shockingly, around 30 percent of youth reported having been sexually abused in the preceding year.8 California, Illinois, and Kansas also performed notably badly, with statewide rates of sexual abuse in their juvenile facilities of 15 percent or higher.

Some 2.5 percent of all boys and girls in juvenile detention reported having been the victims of inmate-on-inmate abuse. This is not dramatically higher than the corresponding combined male and female rates reported by adults or juveniles in either prison or jail. The reason why the overall rate of sexual abuse (9.5 percent) was so much higher in juvenile detention than in other facilities is the frequency of sexual misconduct by staff. About 7.7 percent of those in juvenile detention reported sexual contact with staff during the preceding year.9 Over 90 percent of these cases involved female staff and teenage boys in custody.

Advertisement

Of the youth who reported sexual activity with staff, 63 percent said that no physical force or other coercion had been involved. Indeed, many of them reported that they had initiated the sexual contact, and about half reported that the staff in question had given them pictures or written them letters. While this may not reflect our typical conception of violent sexual abuse, it should be emphasized that much of the staff sexual misconduct in juvenile detention is precisely that.10 And sexual contact of any kind between staff and inmates is illegal in all fifty states, for good reason: the power imbalance between them is so extreme that it makes genuine consent on the part of inmates impossible.11 The notion of consent is even less applicable when the powerless are minors, making the behavior of staff members in these cases even less pardonable.

Although we don’t know nearly enough about the female staff members who commit sexual abuse,12 preliminary indications suggest that many are quite young themselves and new to their jobs in corrections.13 Some of these women may believe themselves to be well intentioned. Yet it is hard to imagine anything less professional on the part of a corrections officer than having sex with a juvenile in custody.

As is the case in adult facilities, blacks in juvenile detention are more likely than whites to report staff sexual misconduct, and whites are more likely than blacks to report inmate-on-inmate sexual abuse. Unlike the National Inmate Survey, the new National Survey of Youth in Custody asked respondents to identify the race of inmates who had sexually abused them. Although there are more blacks than whites in juvenile detention, more whites abused their fellow inmates.

Over half the minors who had been sexually assaulted at a detention facility where they were previously held also reported being sexually abused at their current facility within the past twelve months. This represents an utter failure on the part of juvenile corrections officials. Responsible staff should know, and, we have found, usually do know when children in their care have been sexually abused at other facilities. Since it has long been established that a prior history of sexual abuse makes an inmate more vulnerable to further abuse, it is inexcusable that these children have not been better protected.

Perhaps the most important new findings in the latest NIS come from responses to a series of questions that for the first time addressed the relationship of mental illness to sexual victimization in the prison system. The survey asked inmates whether a mental health professional had ever diagnosed them with a depressive disorder, schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, or anxiety or another personality disorder.14 Approximately 36.6 percent of prisoners and 43.7 percent of those in jail answered affirmatively.15 Several other questions meant to establish the extent of serious mental disorders among the incarcerated confirmed that they were widespread.

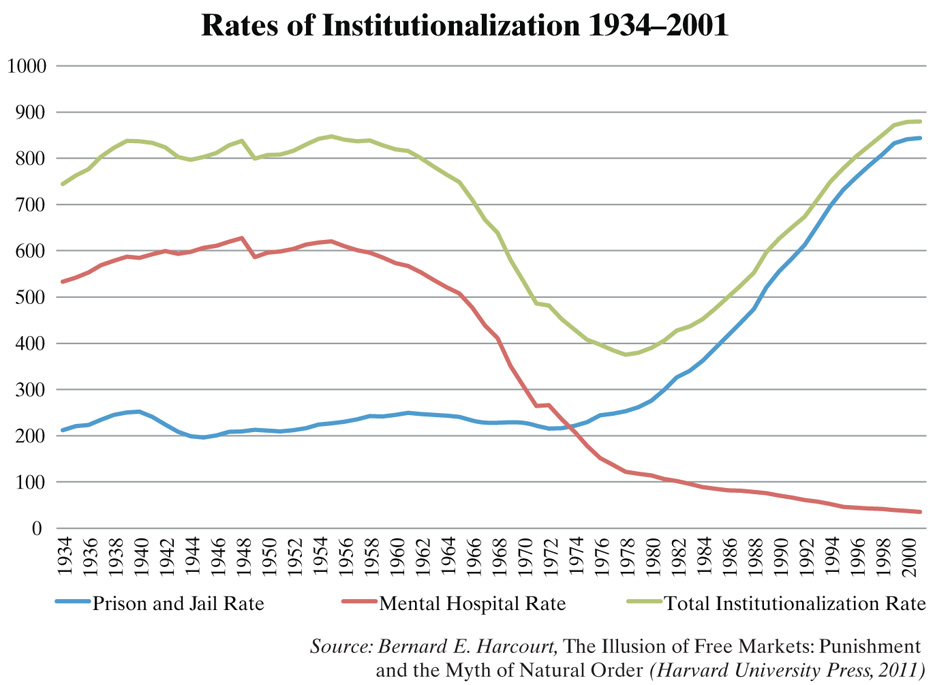

This is not surprising. As has been widely noted, especially since the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School last December, our mental health care system is in disarray. The asylums where people with serious disorders could once receive care were mostly closed down by the end of the Reagan era16—probably for good reason, in many cases, but with no better alternative created to replace them. In 1955, public psychiatric hospitals had beds for 558,239 severely mentally ill patients. Had that number increased in proportion to the growth of the national population, it would have reached 885,000 by 1994. Instead, by 1994, the nation’s public psychiatric hospitals had only 71,619 beds, while general hospitals, community mental health centers, and private psychiatric hospitals had perhaps another 70,000 between them for patients with severe mental illness.

This left a deficit of almost three quarters of a million beds—a number that still represents only a fraction of the 1998 estimate that 2.2 million severely mentally ill people in this country do not receive psychiatric treatment. Improvements in psychopharmacology have not been sufficient to compensate for this lack of institutional care.17 Indeed, a visit to almost any prison or jail makes it distressingly clear that these institutions now house many of the people who need mental health treatment.

Yet it is well documented that inmate health care of every kind is substandard, and prisons and jails are especially ill-suited to give psychiatric care. Far from serving as therapeutic environments, they are too often places of trauma and abuse where the strong prey on the vulnerable. Thus, among prisoners who had been diagnosed with mental disorders, 3.8 percent reported having been the victims of inmate-on- inmate sexual abuse within the preceding year, and 3.4 percent reported staff sexual misconduct.18 For those with no such diagnoses, the percentages of reported sexual abuse were 0.8 and 1.3, respectively. The NIS makes clear that most of the 200,000 people who are sexually abused in our detention facilities every year suffer from serious mental disorders. If our country had a better system of mental health care, many of them, arguably, would not have been imprisoned in the first place.

In addition to 233 state and federal prisons and 358 local jails, the new NIS was administered at fifteen “special confinement facilities”: five immigration detention facilities overseen by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, a division of the Department of Homeland Security; five military detention facilities overseen by the Department of Defense; and five Indian Country jails, one of which is run by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), an agency within the Interior Department. On May 17 of last year, the same day that the Justice Department published a set of strong regulatory standards meant to help corrections authorities prevent, detect, and respond to sexual abuse in prisons, jails, and juvenile detention centers, President Obama issued a memorandum ordering all other federal departments and agencies that operate confinement facilities to devise similar “high standards.”19 Findings from the “special confinement facilities” surveyed by the BJS show just how crucial that directive was.

At the Krome immigration detention center in Miami, for example, there had been periodic reports since the facility opened in 1980 that staff were molesting, raping, and sometimes impregnating detainees awaiting deportation. Year after year, Krome’s officials shrugged off these reports, while the rapists on the staff escaped punishment and retained their jobs.20 As the new NIS shows, this unconscionable situation has yet to be satisfactorily addressed. Krome was the worst-performing of the immigration facilities surveyed, with rates of both inmate-on-inmate abuse and staff sexual misconduct that were substantially higher than the national averages for jails or prisons.

Findings from the Oglala Sioux Tribal Offenders Facility on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota were also disturbing. Anyone who has ever driven through this reservation has probably glimpsed what Peter Matthiessen once called its “despair and apathy, poverty and unemployment, alcoholism, and the random angry violence that besets depressed Indian communities to a degree almost unimaginable to most Americans.”21 It must be one of the saddest places in the United States. The facility, which houses both men and women, is the most crowded Indian Country jail in the nation. And as seems dishearteningly predictable in such a setting, its 10.8 percent rate of reported sexual abuse by staff members was higher than that of any other adult facility covered by the NIS.22 Although the Bureau of Indian Affairs runs many jails in Indian Country, it does not run this one. But the Oglala Sioux jail shares important characteristics (albeit in extreme form) with ones the BIA does operate, and anecdotal evidence suggests that rape is widespread in these federally run facilities as well.

Military detention facilities also performed strikingly poorly in the new NIS. The Army’s Northwest Joint Regional Correctional Facility in Washington had rates of both inmate-on-inmate abuse and staff sexual misconduct that were more than double the national averages for jails or prisons. And the Naval Consolidated Brig in Miramar, California, had more than twice the national average of staff sexual misconduct for prisons, as well as a significantly above-average rate of inmate-on-inmate sexual abuse.23

Of all the divisions of government subject to Obama’s memo, the Defense Department should have responded with the most alacrity. Reports of pervasive sexual assault throughout the military had already turned into a scandal by the time Obama announced his order, and the department’s leaders had sounded as if they recognized the gravity of the problem. Just two months previously, the department had proclaimed that

sexual assault is a crime that has no place in the Department of Defense…and the Department’s leadership has a zero tolerance policy against it. It is an affront to the basic American values we defend.

Nonetheless, the Defense Department’s reaction has, so far, been completely unsatisfactory—the worst of any of the departments and agencies to which the president’s directive applies. It convened a working group to begin discussing standards, but in contrast to the example set by the Justice Department, this was a closed process: no advocates for victims of sexual abuse were permitted to participate, the public received no notice of any measures the department might have been considering, nor were public comments invited. Finally, in February, the department decided not to create standards that would apply to all its detention facilities, but instead to let each separate branch of the military set its own standards. The different branches were given no deadline by which to complete this task and, with the exception of the Army, none seems to be taking it very seriously.

Perhaps leaders of the Defense Department believe that the high rates of sexual victimization suffered by incarcerated and nonincarcerated service members are distinct problems. If so, they are mistaken—first of all, because it seems likely that the same characteristics of the military’s institutional culture account for the high frequency of sexual assault both inside and outside its jails, and second, more fundamentally, because the military has the same obligation to protect all its personnel from abuse, regardless of their status.

People do not simply lose their basic human rights when they are imprisoned. The Supreme Court has clearly stated that rape cannot be part of any legitimate penalty in this country, no matter what crime has been committed. And according to international law, rape in prison is considered a form of torture. One would hope the military would have learned this after Abu Ghraib.24 But the Defense Department’s halfhearted, indeed resistant, response to the president’s order suggests that it has not.

There are, however, encouraging examples of reforms undertaken despite prior reluctance. The Department of Homeland Security fought for years against the idea that it should be subject to the Justice Department’s standards, arguing, despite extensive evidence to the contrary at places like Krome, that it was already giving its detainees sufficient protections against sexual abuse.25 Yet after Obama issued his directive, then Secretary Janet Napolitano immediately expressed her intention to comply with it fully. Her department invited the participation of victims’ advocates and, by December, had already submitted draft standards for public comment. Although its draft has some serious flaws,26 it is probably better as a whole than the one the Justice Department first submitted for public comment. It is not too late for the Defense Department to follow Homeland Security’s example.27

The two recent surveys we discuss here will be the last to measure the incidence of prisoner rape before the Justice Department’s new standards are widely adopted. But the BJS will continue to study this problem, and the surveys it produces in the future should also be of critical importance. They will help show where reform is working and where it is not, which standards are having their intended effect and which still need improvement.

Of course, the effectiveness of any future surveys will depend on the cooperation of the facilities that are selected to participate. This, however, is far from assured. Jails are not under federal authority and officials at some of them, apparently foreseeing that they would perform badly and reluctant to have their mismanagement exposed, have simply refused to let their inmates take the survey. In fact, the number of jails denying access to the BJS has doubled with each new version of the National Inmate Survey.28

But while the administrators of these jails are, legally, within their rights to withhold cooperation this way, by doing so they are openly flouting Congress’s will, since the BJS was first directed to produce its studies by the Prison Rape Elimination Act of 2003—legislation that passed unanimously in both chambers of Congress. In effect, these administrators are announcing that although they have been entrusted with responsibility for public institutions and for the safety of the citizens confined in them, their accountability to the public matters less to them than their own reputations and job security.

If this trend is allowed to continue, if the number of jails refusing to cooperate with the BJS continues to increase, then these crucial studies will soon lose much of their value. After all, many more people go to jail than to all other kinds of detention facilities combined, and most sexual abuse in detention takes place in jails. What can be done about such facilities? The Special Litigation Section of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, which is charged with protecting the civil rights of people in prisons and jails, should assume that any jail refusing to cooperate with the BJS has something to cover up, and should investigate it accordingly. Congress should insist that it do so, and ensure that the Special Litigation Section has the funds it needs for such investigations. Otherwise, the encouraging progress that the government has made recently in its efforts to reduce the epidemic levels of rape in American detention facilities will be in jeopardy.

The Prison Rape Elimination Act not only charged the BJS with undertaking its studies, but stipulated that the Justice Department should investigate the best- and worst-performing facilities identified by the BJS every year and call their administrators to hearings. These hearings and investigations have allowed the Justice Department to examine the policies and practices that foster or discourage abuse much more closely than would have been possible through the surveys alone. Lessons learned in the course of such inquiries have informed many of the department’s standards.

More fundamentally, these hearings and investigations have confirmed that prisoner rape—the rates of which vary widely from one facility to the next—is a preventable problem. Preventing it depends on the effective management of detention facilities: those with low rates of abuse tend to be orderly places, notable for the professionalism of their staff and a culture of respect between staff and inmates. Conversely, those with high rates of sexual abuse invariably suffer from other kinds of mismanagement, disorder, and violence as well.29

Among the facilities called to the last of these hearings was the Orleans Parish Prison (OPP), which, despite its name, is a New Orleans jail. The Justice Department heard testimony that the OPP was inadequately staffed, that it had an “essentially nonexistent” grievance system, and that its classification system failed to identify likely predators and likely victims of sexual abuse, allowing them to be housed together.

All of these allegations were confirmed by a former inmate, A.A., whose story we have mentioned in a previous article.30 A.A. is a gay man who had a prior history of being sexually abused—again, the two characteristics that most strongly predict rape in jail—but he wasn’t asked about either of these things when he was admitted to the OPP. Instead he was put in a crowded communal cell where he was beaten, choked until he passed out, cut with a knife, masturbated upon, and orally and anally gang-raped by other inmates “so many times I lost count.”

There were no security cameras in the cell and no guards around to hear him screaming. He filed grievances claiming that he had been raped, but they went unanswered. (“We dropped the ball on that,” said a representative of the OPP at the hearing.) When he finally found the courage to ask a guard for help directly, he was laughed at and told, “a faggot raped in prison—imagine that.” Other testimony at the hearing suggested that his experience was not uncommon. Such things simply do not happen in well-run facilities.

In April 2012, the Justice Department joined the Southern Poverty Law Center in suing Orleans Parish Sheriff Marlin Gusman, the man who runs the OPP, charging that conditions at the jail violate the constitutional prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. At trial, a cell-phone video was produced that showed inmates in a communal cell injecting and snorting heroin, smoking crack, sorting through Percocet, Vicodin, and other pills, drinking Budweiser tallboys pulled out of a cooler in the cell, shooting dice for handfuls of cash, and showing off a loaded Glock .45mm handgun.31 None of these inmates displays the slightest anxiety about getting caught—but then, the tallboys, the gun (which has never been found), and the cell phone itself could not have been brought into the facility without the staff’s collusion. (As one of the men in the video says, “They’ll do anything for money, so we gettin’ it in.”) In response to the lawsuit, Gusman has reluctantly signed a consent agreement to implement reforms, though he claims that he does not have the funds necessary to improve the jail’s staff or staff training. New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu’s administration has requested that the OPP be put into federal receivership, to be run by the Justice Department itself.

The Justice Department hearing to which OPP administrators were called after the jail’s dismal performance in the 2008–2009 NIS showed that Sheriff Gusman’s leadership had been worse than incompetent—that the citizens entrusted to his care by the state were, in fact, being placed in great danger. Since Gusman was subjected to such public humiliation after participating in one BJS survey, it is not particularly surprising that a unit within his jail was among those denying access to the BJS in 2011. But the fact that the 2008 survey led to such disgraceful revelations of cruelty, mismanagement, and betrayal of the public trust at Orleans Parish Prison only reinforces how essential it is that all detention facilities be held to such scrutiny.

-

1

We do not mean to suggest that the answers to these questions are obvious. Indeed, one of the greatest virtues of the BJS studies is the way their data challenge stereotypes. For example, some people may assume that most inmate-on-inmate sexual abuse is interracial and, therefore, believe that since most victims of such abuse are white, most of those who commit it must be black or Latino. Others may attribute the fact that most victims of staff sexual misconduct are black to simple racial hostility on the part of the corrections staff. As we will see, new findings about the sexual abuse of juveniles in detention call any such assumptions into question. ↩

-

2

More precisely, inmates were asked about sexual abuse at their current facility within the previous twelve months or since their arrival. Many inmates, of course, have not been at their current facility for twelve months. The average exposure time for prisoners ranged from 8.1 months in state prisons to 8.8 months in federal prisons; for inmates in jail it was 3.7 months; and for those in juvenile detention it was 6.2 months. ↩

-

3

See David Kaiser and Lovisa Stannow, “Prison Rape and the Government,” The New York Review, March 24, 2011. ↩

-

4

At midyear 2011, there were an estimated 1,700 sixteen- and seventeen-year-olds being held in state prisons and an estimated 5,700 in local jails. Only about 12.3 percent of these juveniles placed in adult facilities were white. ↩

-

5

Solitary confinement (or “administrative segregation,” as it is often called by corrections officers) can cause devastating, long-term damage to a person’s mental health. And that may be particularly true for minors, whose cognitive and emotional faculties are still developing. ↩

-

6

By contrast, inmates in smaller adult facilities do not experience significantly lower rates of sexual abuse than those in larger ones. ↩

-

7

The BJS listed only fourteen juvenile detention facilities as the best-performing in its new National Survey of Youth in Custody, despite the fact that twenty-six reported no sexual abuse, because twelve of these twenty-six facilities did not have enough respondents to give their results the same statistical significance. These twelve smaller facilities included all those surveyed in Delaware, Massachusetts, New York, and the District of Columbia. ↩

-

8

At the Paulding Regional Youth Detention Center in Georgia, 32.1 percent of the juveniles surveyed reported sexual victimization; at the Circleville Juvenile Correctional Facility in Ohio, the rate was 30.3 percent; and at Birchwood, a juvenile detention facility in South Carolina, it was 29.2 percent. ↩

-

9

Some juvenile inmates reported sexual abuse both by other inmates and by staff, which is why the rates for these separate categories do not add up to the total. ↩

-

10

When inmates have sex with staff members, they do so for a variety of reasons. Some are physically overpowered and violated; some are eager for sex; others agree to it with more complicated, mixed motives, including fear and a desire for special privileges. Of inmates in juvenile detention reporting staff sexual misconduct, 20.3 percent said staff had used force or the threat of force, 12.3 percent said they were offered protection, and 21.5 percent said they were given drugs or alcohol to engage in sexual contact. Some respondents reported experiencing more than one of these kinds of pressure. Only 13.6 percent said that they and the staff with whom they were having sex “really cared about each other.” ↩

-

11

See David Kaiser and Lovisa Stannow, “The Rape of American Prisoners,” The New York Review, March 11, 2010. ↩

-

12

Indeed, we don’t know nearly enough about any of the women who commit sexual abuse in detention, whether they are staff or inmates; more research is urgently needed. We hope to learn more about staff perpetrators of sexual abuse in juvenile detention from another study the BJS plans to publish in the coming year on the basis of data generated by the new NSYC. ↩

-

13

See Allen J. Beck, Devon B. Adams, and Paul Guerino, “Sexual Violence Reported by Juvenile Correctional Authorities, 2005–06” (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2008), Table 10, p. 6, available at www.BJS.gov/content/pub/pdf/svrjca0506.pdf. This study, however, relies on allegations of sexual assault made to corrections authorities. Most sexual abuse in detention is not reported, and the sample of staff in substantiated incidents analyzed in Table 10 may not be representative of all staff members who sexually abuse inmates in juvenile detention. ↩

-

14

This list of ailments comes from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders, Fourth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). ↩

-

15

The reason why jails have a higher proportion of mentally ill inmates than prisons is quite simple: the mentally ill tend to be locked up either because they can’t cope with the larger world—often resulting in homelessness and addiction and a tendency to commit the petty crimes that are associated with these conditions—or because, tormented by their delusions, they are arrested for offenses such as disturbing the peace.

Some among them are so desperate for even the most meager prospect of treatment, not to mention food or a bed, that they deliberately commit crimes in order to be arrested. In any case, the crimes most typically committed by the mentally ill are usually not serious enough to warrant being sent to prison. ↩ -

16

See Oliver Sacks, “The Lost Virtues of the Asylum,” The New York Review, September 24, 2009. ↩

-

17

See E. Fuller Torrey, Out of the Shadows: Confronting America’s Mental Illness Crisis (Wiley, 1998) and Textbook of Hospital Psychiatry, edited by Steven S. Sharfstein, Faith Budington Dickerson, and John M. Oldham (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2009), chapter 1. ↩

-

18

Inmates who had been hospitalized for mental illness in the year before they entered prison—which may provide a more telling indication of acute problems than diagnosis alone—suffered even higher rates: 5.7 percent reported having been sexually abused by another inmate, and 4.9 percent by staff members. ↩

-

19

See David Kaiser and Lovisa Stannow, “Prison Rape: Obama’s Program to Stop It,” The New York Review, October 11, 2012. ↩

-

20

See National Prison Rape Elimination Commission Report, p. 175; available at www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/226680.pdf. ↩

-

21

Peter Matthiessen, In the Spirit of Crazy Horse (Viking, 1983), p. 29. ↩

-

22

All of the inmates reporting staff sexual misconduct at this facility were men. ↩

-

23

Because the Northwest Joint Regional Correctional Facility holds personnel awaiting trial or serving short sentences, jails are its most appropriate comparison. The Naval Consolidated Brig in Miramar holds men sentenced to ten years or less and women from all branches of the military regardless of sentence length, making prisons its closest civilian equivalent. ↩

-

24

There is a considerable amount of professional and cultural overlap between the military and the civilian prison system. On leaving the military, many service people take jobs in corrections. Some people also move from corrections to the military. For example, Charles Graner, who was one of the sexual abusers at Abu Ghraib, had been a corrections officer at two different prisons in Pennsylvania before being deployed to Iraq with a Marine reserve unit. Hierarchical, secretive, and self-protective institutions such as the military and the prison system are marked by dramatic imbalances of power between the people associated with them, by reluctance to make themselves open or accountable to the outside world, and by the belief that their purposes and reputations are more important than any individual suffering that may take place within them. They often seem to let sexual abuse go unchecked and unprosecuted. ↩

-

25

See David Kaiser and Lovisa Stannow, “Immigrant Detainees: The New Sex Abuse Crisis,” NYRBlog, November 23, 2011. ↩

-

26

Inadequate provisions include those for conducting thorough incident reviews after a report of sexual abuse, for informing detainees who make such reports of the progress of subsequent investigations, and for preventing retaliation against those who cooperate with investigations. For a more detailed reaction to the Department of Homeland Security’s draft standards, see the public comment submitted by Just Detention International, available at www.justdetention.org/Group_comment_on_DHS_PREA_NPRM.pdf. ↩

-

27

The Interior Department has also been more active and open about devising new standards than the Defense Department has. The Department of Health and Human Services, which is responsible for undocumented and unaccompanied immigrant children, claims, cynically and absurdly, that many of the shelters in which it keeps these children locked up are not “confinement facilities” and therefore not subject to Obama’s memo. Still, it too has made more progress in creating policies to combat sexual abuse in its facilities than the Defense Department. ↩

-

28

Here is a list of the jails that refused to participate in the latest National Inmate Survey: Covington County Jail, Alabama; Escambia County Detention Center, Alabama; Mobile County Metro Jail, Alabama; Brevard County Jail, Florida; Hillsborough County Falkenburg Road Jail, Florida; Pinellas County North Division, Florida; Paulding County Detention Center, Georgia; Whitfield County Jail, Georgia; Will County Adult Detention Facility, Illinois; Catahoula Parish Correctional Center, Louisiana; Orleans Parish House of Detention, Louisiana; Montcalm County Jail, Michigan; Sandoval County Detention Center, New Mexico; Montgomery County Jail, North Carolina; Delaware County George W. Hill Correctional Facility, Pennsylvania; Northumberland County Jail, Pennsylvania; Carroll County Jail, Tennessee; Marion County Jail, Tennessee; Williamson County Jail, Texas; Kenosha County Pre-Trial Detention Center, Wisconsin. One Indian Country jail also refused to participate in the most recent NIS: the Tohono O’odham Adult Detention Facility in Arizona. ↩

-

29

See “Report on Sexual Victimization in Prisons and Jails,” Review Panel on Prison Rape, April 2012; available at www.ojp.usdoj.gov/reviewpanel/pdfs/prea_finalreport_2012.pdf. ↩

-

30

It was our organization, Just Detention International, which brought A.A. to the Justice Department’s attention. ↩

-

31

The video is available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=E_rRZ9ejTqU. ↩