1.

If we are what we eat—a notion that seems irrefutable in today’s food-fixated United States—then another corollary, at a time when personal identity often derives more from professional pursuits than private matters, would be that we are where we work. Whether that means a mahogany-paneled corner suite atop a high-rise corporate banking headquarters in North Carolina’s Research Triangle, or a Silicon Valley campus designed to feed the infantile appetites of tech geeks, or a hipster freelancer coworking facility recycled from an abandoned architectural relic of some long-ago economic boom, there has never been more diversity in the settings where American office employees spend their workdays.

In Cubed, his impressive but substantially flawed study of the modern office over the past two hundred years, Nikil Saval—an editor at n+1, where this, his first book, began as an essay—develops two subthemes with particular clarity and power. The first and more important is the increasing participation of women in the office workplace beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, a development that entailed a methodical limitation of tasks, pay, and prospects for advancement of women generally. The resulting disparity was not accidental, but began with, and ever since has followed remarkably closely, a standard established for federal employees as early as 1866, when legislators put an annual salary cap of $900 on female government employees, as opposed to a maximum of $1,200 to $1,800 for men.

For those of us whose professional lives have spanned the rise of the feminist movement from the 1970s onward and who have witnessed significant advances in gender equality over the intervening four decades, Saval’s account of the manifold indignities endured by female employees does not come as news. However, in much the same way that Matthew Weiner’s television series Mad Men dramatizes the tribulations of women who attempted to get ahead in what was during the 1960s still very much a man’s world, such effortful oppression can in retrospect seem astonishing even to people who witnessed it firsthand.

Saval makes little mention of Mad Men, but perhaps he felt there was no need to, given his close reading of two pop-cultural period pieces that cover much the same terrain: Jean Negulesco’s soapy career-girl film The Best of Everything (1959), which, like Weiner’s series, depicts the various ways in which women coped with the sexist, pre–Women’s Liberation workplace (in this movie, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s then-new Seagram Building in Manhattan); and Helen Gurley Brown’s best-selling how-to guides, Sex and the Single Girl (1962) and Sex and the Office (1964), which proposed that rather than trying to fend off the personal advances of male colleagues and superiors, young women should exploit their sexual allure to advance their careers.

In her Sex and the Office, Brown documented some rather bizarre office practices, none more so than “scuttling,” a group pastime at a radio station where she once worked:

[Men] would select a secretary or file girl, chase her up and down the halls,…catch her and take her panties off. Once the panties off, the girl could put them back on again if she wished. Nothing wicked ever happened. De-pantying was the sole object of the game.

But as Saval establishes in preceding chapters, Brown’s sisterly counsel on how to succeed in business was hardly novel. In fact, since the outset of integration of women into the workplace a century earlier, there had been pervasive fears that women would capitalize on men’s intrinsic lust by using their feminine wiles for nefarious professional gain. This sexual panic was reflected in Alfred E. Green’s movie Baby Face (1933), which starred Barbara Stanwyck and was promoted with the lurid tagline “She climbed the ladder of success—wrong by wrong!”

As Lily Powers, a hardboiled mill town girl pimped out by her barkeep father, Stanwyck takes the advice of a kindly old German friend who urges her to act ruthlessly in amoral self-interest. “Didn’t you read that Nietzsche I gave you?” he chides. “Be strong, defiant—use men, to get the things you want!”—a veritable Helen Gurley Brown avant la lettre. This cynical admonition takes contemporary architectural form when Lily moves to New York, lands a low-wage job at the Gotham Trust Company, and begins sleeping her way up the corporate hierarchy. Her progress is tracked by exterior shots that pan up the Art Deco skyscraper story by story as she methodically makes it to the top, bagging the defenseless bank president at the summit.

However much the lot of working women has improved in the half-century since Brown’s magnum opus, much still remains to be done in achieving gender equality in work, especially the still-disproportionate compensation gap. In 2012, women made only 77 percent of what men did for full-time work. However, the second of Saval’s most convincingly argued topics, which might be termed the office politics of fear, has proved much less susceptible to improvement through legislation, social pressure, or even a personal sense of right and wrong.

Advertisement

Leaving aside such cinematic portrayals of greed-driven workplace bullying as Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), there are plenty of recent real-life examples to choose from, such as Apple’s legendary cofounder Steve Jobs (whose authorized biography, by Walter Isaacson, showed him to be habitually rough on people under him, though Saval goes rather light on Jobs) and the advertising mogul Jay Chiat, whom I got to know through Frank Gehry when he designed Chiat/Day’s West Coast corporate headquarters of 1985–1991 in Venice, California (colloquially known as the Binoculars Building because its façade incorporates a sculpture by Claes Oldenburg in the form of a gigantic pair of spyglasses), which is now occupied by Google. If Cubed has a prototypical bad boss, it is the megalomaniacal Chiat, one of whose top executives reminisced: “He would terrorize people. When things were going well, he would walk around the agency complaining, moaning and abusing everyone.”

Whether or not the all-male antebellum Manhattan countinghouse as described by Saval at the start of his chronological account was the warmly fraternal and nearly egalitarian place he purports it to have been, there is little question that the exponential growth of American industry and its financial support systems after the Civil War resulted in new degrees of organizational stratification that transformed the way office life was experienced at every level. The sheer numbers of “white-collar” workers (the term was popularized by Upton Sinclair in 1919) employed at the turn of the twentieth century—a fifth of the entire workforce—along with the perceived menace posed by the new, militant industrial labor unions and the rise of anarchist political groups unafraid to engage in terrorism prompted business leaders to embrace novel approaches to labor control, and fear was the favored method.

Into this politically fraught and emotionally volatile atmosphere—which paralleled the rapid rise of the reform-minded Progressive Movement—came one of the most influential figures in the history of labor: Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856–1915), father of industrial efficiency management. Although hailed by many in his day, and long thereafter, as a modern prophet on a par with Darwin, Marx, and Freud, this troubling figure strikes Saval as a “maniac,” which if anything seems an understatement. Taylor’s entire interpretation of work was based on his deeply paranoid and wholly unsubstantiated conviction that modern industrial laborers are essentially slackers determined to do as little as possible on the job. Thus he promoted the idea of vigilant managerial supervision to ensure that deadbeats did not rob their bosses blind.

The effects of Taylor’s baseless theories—which do not take into account a natural propensity for humans to take pride in their labors—were perniciously widespread and tenaciously long-lived. One major reason for the persistence of Taylor’s influence has been the transfer of his prescriptions from blue-collar factories to white-collar offices. Every time you phone a “helpline” to deal with some credit card, online purchase, or other consumer complaint and hear a recording advising you that “this call may be monitored for quality control,” you are experiencing Taylorism’s imposition of worker surveillance.1 Taylor’s pseudoscientific apparatus of observational research was finally given the lie by innovative industrial labor practices systematized in Western Europe after World War II, when cooperative groups of automobile workers, freed from Taylorist notions of quantifiable assembly line efficiency through production quotas, turned out to be much more productive when left to their own more creative devices.

2.

Portions of Cubed are beautifully written, particularly the early section that traces the metamorphosis of the modern office from the pre–Civil War countinghouse, so vividly evoked in Melville’s haunting fable “Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street” (1853), to the high-rise commercial buildings that began to appear in downtown Chicago and New York toward the end of the nineteenth century. However, Saval seems to misunderstand Louis Sullivan’s characterization of the modern office tower’s principal organizational component as the “cell.” By this, the greatest early exponent of the tall building did not mean monastic or penitentiary cells, but instead the basic unit of plant life, which he exalted, at the end of a portfolio of his botanically inspired ornamental drawings for such structures, with the encomium, “Remember the seed germ!”

Moreover, in the book’s last few chapters, whether through authorial haste or editorial neglect, we get sentences such as this description of Philip Johnson, whose career reached its apogee during the corporate office building boom of the 1980s:

Advertisement

Following his conviction that the truth was not found but made by personality, he had developed a conspicuous persona, one that could be easily talked about by carefully selected friends and reproduced in a fawning media.

Regrettably, Saval’s grasp of architectural history is not nearly as secure as his command of literary criticism, popular culture, or social analysis (although he is certainly wrong in asserting that “psychology was the most popular college major of the 1950s,” when it was actually history). Another sign of trouble is his inexplicable choice of adverb when he writes that “Sullivan’s towers were infamously divided just like columns,” that is to say into a tripartite sequence of base, shaft, and capital. Far from there being anything infamous about such a format, Sullivan followed a Beaux-Arts convention that made this one of the least innovative aspects of his skyscrapers.

Later in that same chapter, “Up the Skyscraper,” Saval falls into a common trap posed by one of the three most frequently misrepresented architectural aphorisms (along with Mies’s “Less is more” and Sullivan’s “Form follows function”). He describes the architect and theorist Adolf Loos as “an Austrian modernist who had become infamous for an essay which argued that ornament on architecture should be considered a criminal offense.” Here he refers to Loos’s essay “Ornament und Verbrechen” (Ornament and Crime), which is habitually misstated as “Ornament is crime.” Although Loos linked deviant behavior with a primitive attraction to pattern—a connection demonstrated, he felt, by criminals’ propensity for tattoos—he more reasonably asserted that it is impossible to justify unnecessary ornamentation at the expense of social needs, a view he demonstrated with his handsome if austere public housing projects in post–World War I Vienna.

Beyond such misinterpretations are several factual errors. Henry-Russell Hitchcock was an architectural historian, not an architect. The epochal 1932 Museum of Modern Art show that Hitchcock and Philip Johnson organized was called “Modern Architecture: International Exhibition,” not “International Style,” the title of its accompanying publication. Although Saval writes that Le Corbusier’s “penchant for strikingly large glass panes might have been his most widely followed contribution to the discipline,” this is nonsense. In fact, during the 1920s he advocated narrow fenêtres en longueur (ribbon windows), not large panes of glass. After World War II his concrete-framed tall buildings were notably less glassy than Mies’s skyscrapers, and the windows in Le Corbusier’s buildings were generally screened with louvre-like brise-soleil.

Sometimes Saval displays a callow overeagerness to deliver a punch line.He mentions the much-publicized failure of the window glass of I.M. Pei & Partners’ Hancock Place skyscraper of 1972–1976 in Boston, which began to pop out with alarming frequency soon after it was installed. The author claims that as a result corporations began relocating their “back-office office operations out to the suburbs (possibly fleeing all the falling glass in the cities),” though he must know that such moves were made to cut costs.

Writing of New York’s World Trade Center, he asserts that when “in 1977, the city suffered a catastrophic blackout[,] the towers loomed over the city, lightless, a symbol more forbidding than anything dreamed up by Kubrick in 2001.” But a photograph published on the front page of The New York Times the following day shows that the Trade Center was among the brightest elements of Manhattan’s skyline. Electric lights powered by emergency generators not only illuminated the buildings’ lower stories and rooflines soon after the outage began, but made their reflective aluminum cladding much more visible than other skyscrapers nearby.

Elsewhere the author calls the polished black stele that appears as an enigmatic totem in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) “a Seagram-like black monolith as the symbol of a future in which men would be controlled by their machines.” This same image was invoked by the architect and theorist Reinhold Martin in The Organizational Complex: Architecture, Media, and Corporate Space, where he calls the Kubrick monolith

a minimalist “new monument” worthy of Robert Morris or Donald Judd and an aesthetic precursor of the chess-playing IBM supercomputer, Deep Blue, that merged color-coded corporate identity with the topologies of the black box.2

Tempting though it may be to decipher this gnomic symbol in such specific terms, Arthur C. Clarke—coauthor with Kubrick of the movie’s screenplay—had a more generalized, mystical notion of ineffable spirituality in mind when he dreamed up this Stonehenge-like slab. It was not conceived as a direct indictment of contemporary corporate culture or a prediction of technology’s incipient hegemony.

3.

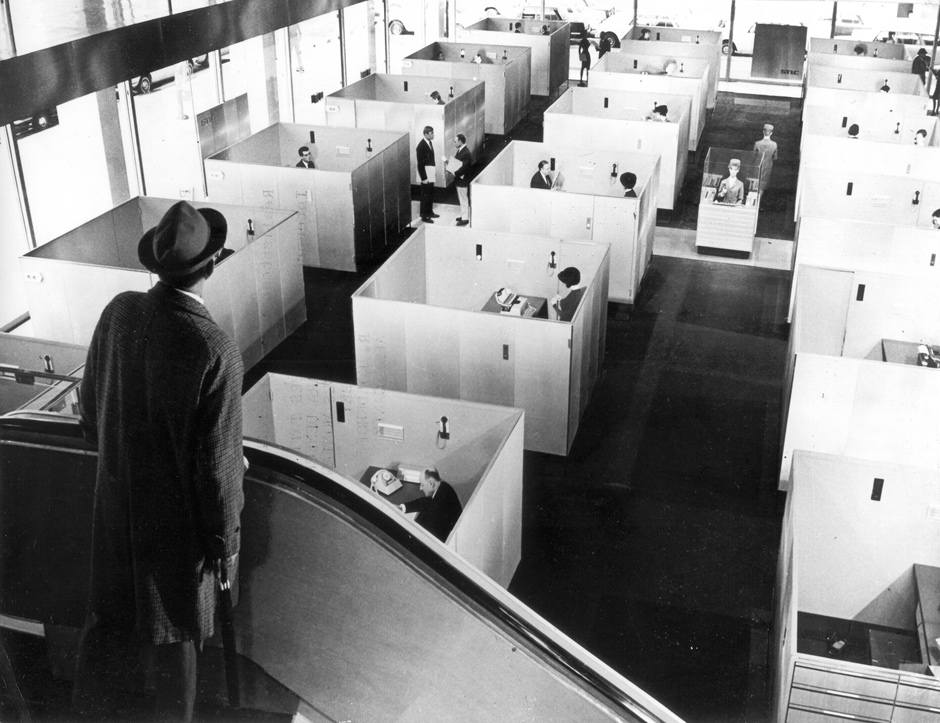

During the 1970s, as an associate editor at Progressive Architecture magazine responsible for its interior design coverage, I had to concentrate primarily on the burgeoning field of open-office planning. Thus it was to Saval’s chapter “Open Plans” that I first turned in order to consider his treatment of the period in office history I’m most familiar with. Happily, he summarizes this pivotal development clearly and perceptively. Much in the same way that the reductive aesthetic of International Style architecture was rapidly debased after World War II by cost-cutting developers, the open office morphed from a high-minded attempt to transform the modern white-collar interior into a more humane environment and became the means to create the cheapest possible office work space.

This revolutionary concept emerged in Germany in the late 1950s as die Bürolandschaft (the office landscape). Although the Bürolandschaft approach was codified by the Quickborner Team (an office planning company based in the Hamburg suburb of Quickborn), the ideas it embodied arose spontaneously during Germany’s rapid postwar recovery. With so much of the defeated country in ruins, and a large part of what business facilities that did survive commandeered by the Allied occupation forces (for example, Hans Poelzig’s I.G. Farben building of 1928–1930 in Frankfurt, then Europe’s largest office structure, taken over in 1945 as the American military’s bureaucratic command post), inexpensive improvisatory retrofits had to suffice for renascent German businesses. (A good sense of what those postwar spaces looked like can be gathered from Arno Mathes’s set decoration for Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1979 film The Marriage of Maria Braun, which recreates freestanding office partitions embellished with trailing philodendron vines.)

Within little more than a decade of its inception, the open office was embraced by American business furniture manufacturers eager to sell not just individual chairs, desks, and filing cabinets, but fully integrated office systems. These modular units incorporated partitions with “task” lighting for up-close illumination, power conduits for the growing number of electrical office machines, and other infrastructural elements that promised unprecedented cost savings as functional needs changed over time.

The welter of midcentury books that characterized the corporate workplace as a wasteland of soul-killing conformity—including sociological studies like David Riesman, Nathan Glazer, and Reuel Denney’s The Lonely Crowd: A Study of the Changing American Character (1950); C. Wright Mills’s White Collar: The American Middle Classes (1951); and William H. Whyte’s The Organization Man (1956); as well as Sloan Wilson’s best-selling novel The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (1955)—may have led some American managers to look favorably on the open office concept. Most ambitious of these adaptations was Robert Propst’s Action Office (1964) for Herman Miller, Inc., the Michigan-based furniture manufacturer best known for its high-style midcentury designs by Charles and Ray Eames, George Nelson, and Isamu Noguchi.

Propst—a polymath with no specific background in office planning—was convinced that a more innovatively designed work space would increase both productivity and creativity. He devised an ensemble of interrelated furniture components to create a flexible “workstation” that (as its trade name Action Office suggests) contravened the essentially sedentary nature of tasks performed within it. This approach was indicated by the inclusion, along with a shelving unit and a conventional work table, of a stand-up desk.

Although advertising for the Action Office used blurred male figures to convey the go-go tempo of the early 1960s, the new product line was a commercial flop, which prompted Propst to come up with a more salable revised version, Action Office II (1968). The major difference between the two was that the second version introduced the freestanding partitions that have become the most detested aspect of the open office. As shown in newly depopulated ad schematics of Herman Miller for Action Office II, these movable walls were at first splayed at obtuse angles to convey a spacious, nonregimented feeling.

However, it took corporate customers no time at all to set them up in rigid right-angled formations, and for furniture companies less concerned with quality to flood the market with cheaper, flimsier knockoffs. The sharp recession of the early 1970s and the “stagflation” that plagued the American economy throughout the rest of that decade increased the acceptance of the open office for all the wrong reasons. Open-plan spaces that could be cheaply and easily reconfigured as the number of employees ebbed and flowed with layoffs and hirings became the new order of the day, and have remained so. Today an estimated 60 percent of American office workers are consigned to cubicles that are disliked, Saval tells us, by 93 percent of their occupants.

The most common complaint among disaffected denizens of these so-called cube farms is a pervasive lack of acoustic privacy. Early on, Herman Miller tried to compensate for this drawback with “white noise” machines that emitted sounds somewhere between radio static and running water, though many found the nonstop background buzz annoying in its own right. A common result—and likely one not unwelcome by Taylorist managers obsessed with productivity—is that many workers feel unable to make confidential phone calls from their own desks. (Two colleagues of mine, one at an architecture magazine and the other at an exhibition design firm, routinely ask me to ring them up later at home, where they can speak without fear of being overheard by eavesdroppers.)

Since 1989, the patron saint of the cubicle-bound worker has been Dilbert, the bespectacled, white-collared, nebbishy principal character of the eponymous syndicated newspaper comic strip created by Scott Adams, with lucrative spinoffs including an animated TV series, a video game, and a veritable merchandising industry aimed at the same inhabitants of warrens satirized by the cartoon. Compared, say, to Gary Trudeau’s politically acute Doonesbury, Dilbert is mild stuff, expressing a generalized feeling of helpless malaise about the banalities and inanities of modern office life. After the terrors of the Great Recession that began in 2008, however, many inhabitants of cubicles no doubt feel lucky to have even a tiny, partitioned patch of corporate turf to call their own.

A somewhat darker view of the contemporary corporate workplace is projected on the Internet by The Zombie Office, a webcomic-cum-merchandising-site with the slogan “The zombie apocalypse is here, now get back to work.” Tying into the current vogue for horror movies that deal with zombies, the confluence of these once-human creatures and the deadening atmosphere of so many offices implies that present-day white-collar workers are among the walking dead (or the undead, as zombies are thought to be). If, as seems the case, feelings of endemic wariness and fear now pervade many parts of the American workforce at every level, zombie fantasies are not an unreasonable way of summing up this uncertain moment in the history of labor. The constant reduction of cubicle dimensions as a cost-cutting measure (the national average dropped from 90 square feet in 1994 to 75 square feet in 2010) leads Saval to suggest that the office of the future could well be either a sharp increase in working at home or an open public space that provides Internet access.

One recent alternative to the permanent office is the coworking space, a communal set-up that carefully avoids mimicking the pathetic “outplacement” facilities used by corporations to give laid-off white-collar employees temporary offices (or cubicles) that soothingly replicate the look of their previous surroundings while they try to land another job. Coworking spaces for freelancers and small businesspeople, such as Philadelphia’s Indy Hall and GRid70 in Grand Rapids, Michigan, follow more informal Silicon Valley prototypes in deemphasizing strictly demarcated personal territories and hierarchical markers such as corner offices or closable doors. They flaunt whimsical decorative flourishes that range from funky thrift-shop furnishings to frat-bro game tables (foosball, ping-pong, billiards) that allegedly signify freedom from 9-to-5 drudgery. Most importantly, coworking spaces, which are rented for short-term subscription fees, do not entail the substantial capital outlay of permanent offices.

Of course, some sectors of our national economy are booming, none more so than the high-tech industry, and it is thus unsurprising that most new thinking about how the workplace should be physically arranged is emerging from there. Saval reports on his visits to thriving Bay Area information technology companies—Google in Mountain View and GitHub in San Francisco—where he finds the new Silicon Valley paradigm of the office-as-playpen, largely modeled, he says, on undergraduate dorm life at Stanford in nearby Palo Alto (where many leaders in the high-tech industry studied). By providing their predominantly young, male, and often unmarried “knowledge” workers with a wide array of free services and recreational diversions in an agreeably casual atmosphere surrounded by (suburban) nature, tech companies have been able to gently coerce their hirelings into spending much more time on the job than they’d be likely to in a generic cube farm.

Accustomed to pulling all-nighters in college, and inevitably plugged into the electronic devices that allow nonstop work to seep into every waking hour, the high-tech contingent of the post-Dilbert generation may not be subject to the anxieties that burden the growing ranks of “permatemps”—the part-time workers who comprise the fastest-growing sector of today’s economy because their employers do not have to provide them with costly benefits (especially health care) mandated for permanent staff. However, these lucky full-time exceptions to the present-day norm are not immune from the yawning pay gap that increasingly separates average workers from top management (unless they have equity in a start-up operation, generous stock options, or other emoluments used to entice talent to fledgling operations in lieu of high salaries).

What has not changed much throughout the two centuries that Saval examines in his delightfully readable, sporadically penetrating, and regrettably uneven study is the still-persistent belief that the physical aspects of an office will strongly affect the quality of work produced there. This is often an illusion. For, as with all other architecture and design, the way we make our offices offers an accurate reflection of our values, and not a formula for improving them.

-

1

See Robert Skidelsky, “The Programmed Prospect Before Us,” The New York Review, April 3, 2014. ↩

-

2

MIT Press, 2003, p. 227. ↩