In the first decade of the twentieth century, Luisa Capetillo walked through the mountains of Puerto Rico’s Cordillera Central. The “red amazon,” as one friend called her, had already earned a reputation for being the island’s own Emma Goldman. Capetillo was an anarchist, a feminist, an advocate of free love. From her start as a lector, hired by cigar rollers to read them books as they worked, Capetillo had grown into a prominent labor organizer in the Free Federation of Workers. In Havana, she became the first Puerto Rican woman to be arrested for wearing pants. In 1909, Capetillo travelled the length and breadth of Puerto Rico, on foot, train, and horseback, organizing and agitating workers as part of an FLT campaign called Crusade of the Ideal. During these travels, she was shaken by the poverty she saw. Of the exploited workers, Capetillo wrote: “You are the eternal mine from which the bourgeoisie and the religions extract enormous treasures… You are the immense building blocks on which the governments rest their suffering backs and tyrants rise to power. You are the rungs upon which kings and emperors, ministers and priests, confidently rest their feet.”

In November 2017, Puerto Rico both is and is not a country Capetillo would recognize. There are still the fragile wooden houses in the campo, still the intense domino games, the close-knit families, the poverty and Catholicism-infused espiritismo that Capetillo herself practiced. But Puerto Rico is also a captive market for US products. The island has more Walmart stores per square mile than any place on earth; its concrete suburbs are packed with fast-food outlets and strip malls. Pharmaceuticals and hedge fund debt have replaced coffee, tobacco, and cane.

Two weeks after Hurricane Maria hit, aid remained a bureaucratic quagmire, mismanaged by FEMA, the FBI, the US military, the laughably corrupt local government. The island looked as if it were stuck somewhere between the nineteenth century and the apocalypse. But leftists, nationalists, socialists—Louisa Capetillo’s sons and daughters—were stepping up to rebuild their communities.

Natural disasters have a way of clarifying things. They sweep away once-sturdy delusions, to reveal old treasures and scars.

I flew to San Juan at this moment, on a plane filled with other Puerto Ricans, their bags, like mine, entirely packed with aid items. I had not visited the island since I was eight, a reluctant visitor to mis abuelos house in Bayamon. For years I had told myself I would return, but I put it off, convinced, like so many solipsists in so many diasporas, that the place would always be there waiting for me. My friends Luis Rodriguez Sanchez and Christine Nieves lived in Barrio Mariana, a small town in the same mountains where Capetillo once walked. I was staying with them, documenting their efforts to build a community soup kitchen. They had neither power nor water nor cellphone signal; just heat, an old community organization called ARECMA, friends in the US, a mountain spring, and the generous, fast-healing earth.

Over the next month, Luis, Christine, and ARECMA, took over the group’s storm-ravaged hilltop center and set up the Proyecto de Apoyo Mutuo (Project for Mutual Aid). I flew back home to New York before I could see it open. They began by feeding hundreds of people a day, with rice, pork and beans, rather than the MREs and tropical-flavored skittles provided by FEMA and the military. Then they added a weekly health clinic. Classes in chess and bomba dance for bored kids (the vast majority of schools remain closed). A free meal delivery service for the elderly. Potable water. Even Wi-Fi. Their Proyecto is one of a rapidly growing network of autonomous, self-managed Centros de Apoyo Mutuos (CAMs), which now also exist in Caguas, Río Piedras, La Perla, Mayagüez, Utuado, Lares, Naranjito, and Yabucoa. Each offers a communal dining room, with delicious free food. They distribute goods donated both by locals and those abroad, and they organize brigades to clear roads with machetes and axes. The CAMs are established by and for their communities, and in the course of providing aid, they create spaces for discussion and political organization. In theory and in practice, they resemble the solidarity networks that left-wing Greek activists used to survive their country’s financial crisis. In the words of AgitArte, a radical San Juan art collective deeply involved in the CAMs, they don’t exist just to address urgent needs, but “to combat the onslaught of disaster capitalism and its henchmen.”

Many of the CAMs are steeped in the ideas and symbols of Puerto Rican nationalism that the US government has fought for over a century to suppress. Puerto Rican independence has never been popular at the polls (in the widely boycotted 2017 plebiscite on Puerto Rico’s status, it received 1.5 percent of the vote, of the 23 percent of the island’s voters that cast a ballot). But independence fighters remain symbols of autonomy and dignity for many Puerto Ricans—and Donald Trump might be the strongest argument for their ideas. Perhaps Puerto Rico’s most famous nationalist is Pedro Albizu Campos, the charismatic, uncompromising founder of Puerto Rico’s Partido Nacionalista. who spent twenty-six years in US prisons before his death in 1965. His party’s efforts so frightened the US government that Puerto Rico’s governor, Luis Muñoz Marín, signed the Ley de la Mordaza, or gag law, which, from 1948 to 1957, punished with lengthy prison terms all expressions of pro-independence sentiment, including songs, advocacy, and any display of the now-omnipresent Puerto Rican flag, even in one’s own home.

Asked how her project relates to the man whom my father sometimes respectfully calls Don Pedro, Christine Nieves said, “Proyecto Apoyo Mutuo and other similar Mutual Aid efforts are born from the acknowledgment that we matter and we can solve our own problems as Puerto Ricans—is about dignity and self-respect—and so was Albizu’s vision. We have one and the same core: self-love and a strong conviction in our capacity to build community.”

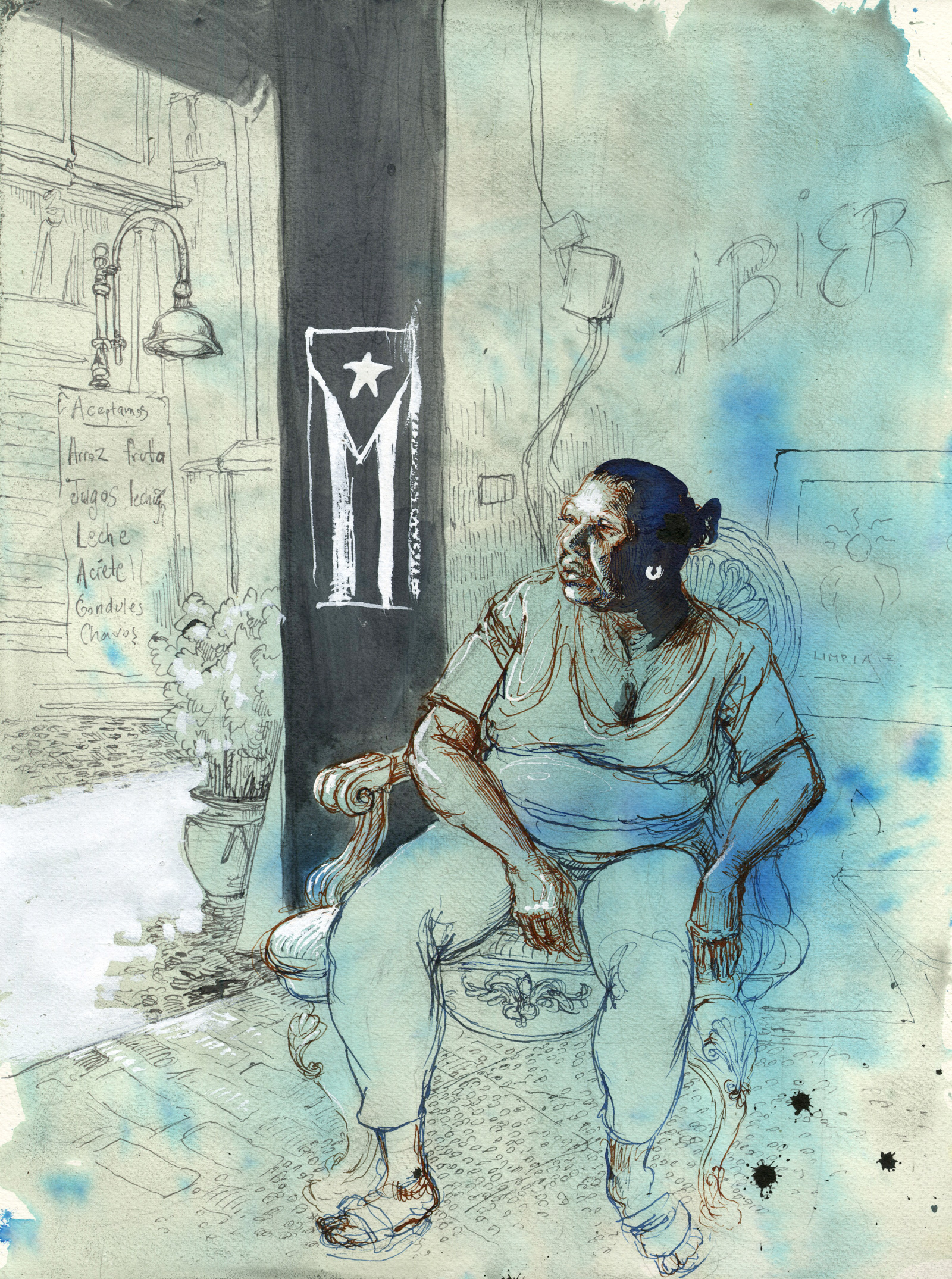

Molly Crabapple, 2017

After hurricane Maria, Luis Rodríguez Sanchez and Christine Nieves raised a Puerto Rican flag in their home in Barrio Mariana, Humacao. Though Puerto Rican flags are now ubiquitous, they were banned from 1947 to 1956 under the Ley de la Mordaza, or gag law, along with all other expressions of nationalist sentiment.

One of those dedicated to realizing Albizu’s vision today is Oscar López Rivera, the independence fighter who was pardoned by Obama after decades of imprisonment for his involvement in a paramilitary organization that carried out bombing attacks on the US. López Rivera was back in the news earlier this year after New York’s Puerto Rican Day Parade chose him as an honoree. But after some of the parade’s sponsors threatened to withdraw, he decided to march as a private individual. Today, he is working as a volunteer serving food at the CAM in Caguas.

The Centros de Apoyo Mutuo are only some examples of the countless grassroots projects that reflect the spirit of Luisa Capetillo. Taller Salud, a radical feminist clinic in the largely black city of Loíza, has been rebuilding the homes that Irma destroyed. There is also the Colectiva Feminista en Construcción, founded in 2014, which now delivers food, supplies, and money for tarps. Lawyers teach Puerto Ricans how to fill out FEMA forms in their squatted building in San Juan. The Santurce punk club, El Local, whose sweat-soaked, cigarette-blurred nights I sketched, operates a community kitchen that feeds six hundred people a day. Many of these groups honed their activist skills fighting the punishing austerity cuts that the US imposed to address Puerto Rico’s debt crisis.

Farmers like Daniella Rodríguez Besosa, who owns a farm called Siembra Tres Vidas, will also play an essential part in returning the island to normal. Puerto Rico imports about 85 percent of its food even though its land is so fertile that both the American and Spanish colonial governments once feared that peasants, so well fed by the abundance of fruit, would not be induced to toil in a sufficiently profitable fashion. Because of the economic crisis, young city people began returning to the land years before Maria, but the hurricane has now made agriculture a matter of both autonomy and survival. And there are the innumerable Puerto Ricans, of all philosophies and backgrounds, who drove into the mountains to help however they could. They may never have heard of Capetillo, but their determination, independence, and grit are of the same type.

The efforts of the islanders are matched by help from the diaspora of which I am part. In the Bronx, a Puerto Rican boxing gym and cultural center named El Maestro has collected and distributed a hundred tons of aid. On one of the gym’s walls is a mural celebrating the independence fighters, Lolita Lebrón, the Macheteros, Ramón Emeterio Betances, Pedro Albizu Campos. Organizers for the New York arts collective DefendPR have toured the island with solar-powered movie screenings, and are helping rebuild the Paloma Abajo neighborhood in Comerio.

Many Puerto Ricans told me that they believe the poor response from the federal government and the slow pace of the recovery are deliberate, part of a strategy to depopulate the island, so that it can be remade as a luxury hotel-filled playground for the rich. More than 139,000 Puerto Ricans have arrived in Florida since Maria—so many that Orange County is considering making a displaced persons’ camp near the airport to house them. And many of the people I spoke to while in Puerto Rico had plans to leave.

While San Juan and a few other cities are starting to recover, the countryside is not. It is now estimated that as many as nine hundred people may have died as a result of the hurricane. The federal government is offering Puerto Rico an aid package that contains over $4 billion of loans, while local officials of both major parties demonstrate egregious corruption, incompetence, and sloth. A viral video showed alleged FEMA officials partying at a hotel bar, while a much-shared post by an aid worker accused Unidos—the charity run by Puerto Rico’s first lady, which received millions of dollars from celebrities—of hoarding donations in the convention center and then distributing them to municipalities they hoped would support the incumbent governor in the next election.

In Arecibo, a domestic violence shelter named for Luisa Capetillo remains closed because it lacks fuel for its generator. With each day that the lights remain off, the taps remain dry, the schools remain closed, the leptospirosis remains swimming in the water, staying in one’s home becomes more of an act of will. Across an overpass in San Juan, a graffiti artist asks: “Puerto Ricans, when will we realize they are lying to us?”