In response to:

Heroines from the February 11, 1971 issue

To the Editors:

The opening arpeggio of quotes in Kazin’s “Heroines” [NYR, February 11] does indeed prove that women have been regarded as valuable objects d’art by past male writers. I thought that beginning meant Kazin was going to discuss the opposing idea that women are people. But not so. There follows instead an essay on women writers intended to show them as more up-to-date objects, robot creators who respond in various ways to the biological and social pressures of femaleness.

Thus Katherine Anne Porter’s shift toward bitterness as she revised No Safe Harbor into Ship of Fools is not to be thought attributable to some experience in Porter’s life; it must be an aging woman’s disenchantment with female biology. The hint is, of course, that a male writer would accept the passage of youth and the arrival of wrinkled unattractiveness in better form, just a minor part of life. And the Flannery O’Connor characters who are resentful of power, grotesque in being victims, come from her being “as a woman even more reduced to inaction than most women.” Why do they not arise from her individual situation as described by Kazin in that same paragraph, “She inherited the dread circulatory disease of lupus,…knew she had it from the time she began to write. She was a bluestocking in pseudo-aristocratic surroundings.” Being female, Kazin says, overrode in importance those circumstances.

Sexual conflict does appear to be at the root of Carson McCullers’ novels; indeed, like the astute critic he usually is, Kazin points it out as a theme in The Ballad of the Sad Café. But with discussion of Joyce Carol Oates, we are back to supposing, despite what analysis shows, that gender is at the root of all. Of Oates’ “peculiar gift for moving with people’s lives as they [italics Kazin’s] understand them” is assignable to femaleness, what are we to make of William Faulkner’s and William Styron’s like sensitivity in The Sound and the Fury and Lie Down in Darkness?

At the end of every analysis, Kazin drags his writer back into the sex-motivation category that the discussion of individual works may have ignored or subordinated. Why can’t he admit consciously what his critical intelligence persists in showing him? Some women write out of sexual motivation, some don’t, just as not all men are concerned with machismo, though Hemingway may be. Taking note of women’s liberation ideas, as Kazin seems trying to do, means considering them as persons, not finding a new category to lump them all together in.

Evelyn Feltner Moulton

Bloomington, Illinois

Alfred Kazin replies:

Mrs. Moulton has certainly gone out of her way to make her pitch. I didn’t write an essay on women writers in order “to show them as…up-to-date objects, robot creators who respond in various ways to the biological and social pressures of femaleness.” Mrs. Moulton is as suspicious about one’s use of what she has extrapolated as “femaleness” as a Soviet policeman is about a muzhik’s extra cow. But I wasn’t writing about “femaleness” as such, only about some gifted women writers. I don’t think that Hemingway as artist was concerned with “machismo” alone, and I couldn’t possibly think of Porter or McCullers or O’Connor as “robot creators who respond in various ways to the biological and social pressures of femaleness.” I don’t know what a “robot creator” is—Mrs. Moulton’s vehemence on “femaleness” (and male writers) is utterly inapplicable to what I wrote.

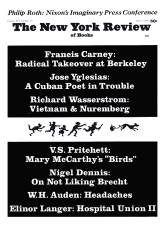

This Issue

June 3, 1971