Dan Jenkins is just playing around in Semi-Tough, his novel about a New York Giant running back and his friends during the week before a Super Bowl. He has written not a real novel, but a pretty good book of jokes. Here is Billy Clyde Puckett, hero-narrator, when asked what it’s like to play pro football: “Aw, we don’t like it so much. Mainly, we just like to take showers with niggers.” And Big Ed Bookman, Fort Worth oil man: “I just don’t give one goddam how many transplant cases are walking around healthy. They’re supposed to be dead, like God wanted ’em to be.” To which Shake Tiller, wide receiver and Billy Clyde’s roommate, answers: “If God had wanted man to drink more, he’d have given him two mouths.” Jim Tom Pinch, newspaperman, defines a NBA basketball game: “Ever twenty-four seconds ten niggers jump up in the air.” Barbara Jane Bookman, Shake’s girl, daughter of Big Ed, and childhood friend of Shake and Billy Clyde, as she is taking off her levis at a party the night before the Super Bowl: “It might not be the best you’ve ever seen. But, well. Some people say it smells better than a soft new Italian loafer. And some people say it tastes better than strawberry shortcake.” To which Shake answers: “What her wool actually is, is semi-tough.”

The book is almost all one-liners and anecdotes, and so long as it is innocently that, Semi-Tough is semi-good. No one is going to like all the jokes, but anyone who reads a book about pro football by a Sports Illustrated writer is going to like quite a few. The assumption is that we want to listen to the best running back in the game, especially if he will talk about singles living in New York and LA, about the vagaries of his teammates, about racism, ad agencies, and Texas. The book is fine so long as it tries to capitalize on that assumption. Billy Clyde, Shake, Barbara Jane, and her parents go to a restaurant called Beef Jesus:

“Hi there,” said the waiter. “I’m Jesus Harold. I’ve come back to serve you.”

Big Ed spoke half to Jesus Harold and half to his menu.

“I don’t know where you came back from, young man, but it looks like you didn’t grab anything but your underwear when you left,” he said….

“To start,” said Jesus Harold, “I’ve got avocado and aku, cold, of course, with Macadamia nut dressing. Very nice. I’ve got spinach and mushroom pie. Unbelievable. I’ve got asparagas soup, cold, of course, with some heavenly little chunks of abalone in it. I’ve got celery spears stuffed with turkey pâté. Incredible. And I’ve got civiche without pitted olives. It’s terribly marvelous.”

Big Ed looked up at Jesus Harold and said:

“Now tell us what you’ve got to eat.”

I was on Big Ed’s side for once.

The trouble comes whenever Jenkins takes himself more than semi-seriously. Instead of having Billy Clyde say he just likes to take showers with niggers he also has him worrying whether we’ll think him a typical Texas bigot. Instead of letting the simple sexism of all that talk about lungs and wool generate whatever fun it can Jenkins insists that Barbara Jane take up the last episodes of the book talking very seriously and uninterestingly about real life. Instead of letting Billy Clyde tell jokes against Texas and New York he pretends that Billy Clyde and Shake and Barbara Jane were all along working hard to get out of hateful Texas. He even has Billy Clyde describe Shake’s seriousness about life this way: “Shake reads just about everything he can, whether it’s politics, novels, or something interesting.”

The jock sniffers in Jenkins’s audience won’t mind this kind of flaw, but presumably Jenkins seeks a larger audience. If he wants to move away from the jokes toward the bitter-sweet, he needs a more capacious narrator, perhaps like Henry Wiggen of Mark Harris’s fine and by now mostly forgotten books about baseball. If, on the other hand, he wants to make the jokes into a genuine view of life, he might see how Terry Southern makes jokes both funny and outrageous. My guess, though, is that Jenkins needs to be more interested in football, whatever direction he wants to go. The worst thing in the book is Jenkins’s coyly pretentious refusal to describe how the Giants won the Super Bowl. If he can’t engage himself in the game his readers can’t do much more with the jokes than count the hits and misses and gradually forget even the pretty good ones because they have too little to sustain them.

Advertisement

Probably no one should try to use Steven Millhauser’s Edwin Mullhouse: The Life and Death of an American Writer, 1943-1954, by Jeffrey Cart-wright as a model, though it is a very interesting book in a number of ways. We’ve had books with titles like this one lately, and Edwin Mullhouse comes complete with J. C.’s “Preface to the First Edition” and an “Introductory Note” by someone called Walter Logan White. It makes for a pretty grim beginning, all that weight placed on a hero who dies at age eleven and who is the author of a masterpiece, Cartoons.

Nothing Millhauser does by way of being satiric about biographies helps. Cartwright is twelve when he writes the biography, says on the first page that Edwin Mullhouse is America’s most gifted writer, launches into a description of the first meeting of Jeffrey, at six months, and Edwin, at three days. To follow that with a long list of Edwin’s first sounds, “breath-taking combinations of the buzz and drool,” is to encourage readers to go no further. If Dan Jenkins will get more readers than he deserves because he begins with good jokes, Steven Millhauser will get fewer than he deserves because his first pages fall into that trap of satires which makes them become the thing they deride.

After the first fifty pages everything begins to pick up, and the flaws begin to seem more like risks taken than silly blunders. Millhauser knows what usually goes wrong with books about children, namely over-inflation of the child’s experience either because of a first-person narrator or because of an implicitly adult narrator who hovers over, the child and makes the experience impossibly sensitive and aware. The device of the biography allows Millhauser to be full and dense about Edwin’s life, but in a reasonable, detached way; that the biographer is a childhood friend is a device that gets rid of the falsity of the hovering adult. Had Millhauser trusted his plan more he might have avoided the jokes at his narrator’s expense, shortened the book, and lost nothing important.

The biographer when he is also a childhood friend will never abandon his sense of how many ordinary experiences his hero has, so that if the hero is to be made worthy of a biography it will not be so much because of the extraordinary things he thinks or does as because of the quality of his investment in the ordinary: reading, counting, doodling, going to school, discovering comics and cartoons, chasing girls, playing board games, exploring the neighborhood. The following is not about Edwin, but it shows very clearly what Millhauser-Cartwright can do:

Penn had begun subscribing to several comic books at the age of four; from the age of five he had made it his business to purchase every single copy of every single series put out by Walt Disney: the monthlies, the bi-monthlies, the quarterlies, and the annuals. He was always filling in gaps in the early years, as some people fill in gaps in stamp collections, and he kept up with several other publications as well as he was able. He eagerly questioned Edwin about his collection and snorted faintly through his sharp nose when Edwin, looking away, confessed to owning “not too many” (actually no more than a dozen at this time).

Penn’s passion for comic books, incidentally, was not all-embracing; like Edwin after him, he had no interest whatsoever in what he called adult comics: detective stories, adventure stories, horror stories. For Penn, Superman and Dick Tracy and hairy monsters were real inhabitants of the real world, of no more interest to him than the radio news reports which he had stopped listening to at the age of three (World War II, for Penn, was a long adventure serial that his father listened to all night long, and Penn loathed radio serials).

Only in the world of cartoon animals was Penn able to breathe with some measure of freedom. But even his beloved animals, he felt, were infected by a taint of caricature that rendered them almost real; he longed for creatures of absolute fantasy, bearing no relation to anything in this world…. He spoke of worlds inside a stone, a flame, a snow-flake, a flash of lightning, a mushroom. He spoke of creatures made of ice, of glue, of lightning, of green.

Playful and inventive, but each sentence adds something, takes us further.

What is entrancing is the way the intense scrupulousness of the biographer meets and illuminates the intense scrupulousness of Penn’s collecting and exploring the worlds of cartoons. Penn himself could never describe this as efficiently or unfeverishly; an adult could never be so unpatronizing; a casual friend who did not have the mantle of the biographer would have no need to be so careful. What Millhauser can bring to writing about childhood is a rare fusion of the luminous and the detached, of the playful and the grave.

Advertisement

But to try to amplify this method into Edwin Mullhouse as America’s most gifted writer is something else again. Millhauser-Cartwright believes all children may well be born geniuses:

The important thing to remember is that everyone resembles Edwin; his gift was simply the stubbornness of his fancy, his unwillingness to give anything up. In the Late Years, when most of his contemporaries were already being watered down by a dreary round of dull responsibilities and duller pleasures, he alone refused to be diluted, he alone continued to play.

The idea is of course at least as old as Wordsworth, but novels, or biographies, must make it stick. Millhauser can describe Edwin’s stubborn refusal to be diluted without breaking Cart-wright’s firm hold on the day-to-day life of a friendship, but he also needs eventually to give Edwin something to write about. There’s little gained if Edwin’s stubborn fancy yields him only a continued grasp of his three-year-old fancies. But since Millhauser doesn’t want Edwin himself to be extraordinary he must bring in extraordinary things from the outside for Edwin to be shaped by and have as his subject.

Edwin is fascinated by the distortions of the real offered by cartoons and comics. Millhauser obliges by giving him as real life distortions the comic-book mad Penn, then a girl who turns out to be a witch and who burns herself up when she burns down her house, then a boy who is possessed by violence, who transforms games into matters of life and death, who murders and is himself killed by a cop. Millhauser has Cartwright chronicle all this with the same intense detachment with which he describes Edwin’s learning about holidays in the first grade. But it is never convincing, because so much is happening that Cartwright cannot understand. Edwin’s extraordinariness, thus, always seems something given him by Millhauser, not something he himself grasps or achieves.

But if Edwin Mullhouse, especially in its late stages, is not successful, it is often very good, and in original enough ways to lead one to believe that Steven Millhauser is a writer who is going to get better. His sense of play gives him a vital relation between detail and emotion, and that justifies his fancy and fashionable narrative tricks as few similar novels do. Most playful writers have been leaving the recognizable earth of late, which may well be their privilege, but it is good to see a sportive novelist engaged in trying to unearth the mysteries of ordinary life.

Doris Lessing, we know, is all seriousness and a mile wide; even when she is being somewhat offhand or experimental she is never what anyone would call playful. What is remarkable is not that at her middling or her worst she is ponderous, but that at or near her best she is free of this vice, and inventive and clear in her vision. Little in her latest collection of stories and sketches, The Temptation of Jack Orkney, is going to wind up part of her most admired work, but no one can make being dead serious seem so interesting, and she stamps herself in her slightest work as a major writer.

This collection contains work done since 1963, and if, as seems likely, it is arranged chronologically, it shows more ups and downs than it does any clear development. Doris Lessing fans will note the way the ideas and emphases have been changing—the world is coming to an end and only “irrationals” or “others” can see it clearly; men are increasingly used as protagonists—but such considerations can safely be left to those who want to embalm her in some intellectual scheme. What is interesting here is that the work can be good or bad whatever the period, or emphasis, or subject.

In a sense Lessing’s best qualities as a writer exist independently of her ideas, so that sometimes the ideas illuminate a character or situation, and sometimes they bury it. The two best things here are a story, “An Old Woman and Her Cat,” and a chronicle, “A Year in Regent’s Park.” Both apparently were written in an otherwise fallow period, between The Golden Notebook and The Four-Gated City. They are different from each other and from her later work, and these facts in themselves show us something about Lessing as a writer that no pursuit of her ideas or account of her development can reveal.

Doris Lessing’s genius is to be able to see longer into her materials than one would have thought possible. She starts with characters and situations that seem to have clear outcomes: this woman will die, this marriage cannot survive the next crisis, this world will blow up soon. Then, without denying the expectations created by such an opening, Lessing reaches her putative climax or solution and then moves on to some further action which seems both unexpected and right.

In her best work she keeps on providing these surprises, one after another, seeing further and further into apparently exhausted subjects. For this reason she is best thought of as a prophet or a visionary, and not, in the usual sense, as a thinker; when she is most disturbing she is simply pushing deeper into situations and their consequences. Conversely, when she most closely resembles the ideological creature she is often mistaken for, she is at her weakest; it is no surprise that the worst piece in this book, “Report on the Threatened City,” is the most dogmatic and inflexible, or that the best two are wonderfully personal and responsive pursuits of directly grasped characters and circumstances.

Which brings us to London, to the fact of London for Doris Lessing. We know, because she has told us so clearly, that the ardent young communist she was in Salisbury had no chance, no subject. We can see now, and perhaps she can too, that her density, her liberating subject, her prophetic power, are all the products of her twenty-year love affair with London. It has tortured her, and given her a nightmare vision of the future, but it has, by giving her a sense of what would be lost if it were lost, given her a way of making life seem precious. In “An Old Woman and Her Cat” we have this, a paragraph from early on, and note both the pervasiveness of the city and the way it offers Doris Lessing her vision:

After her husband died and the children married and left, the Council moved her to a small flat in the same building.

We are, with mention of the Council, alert to disaster, and it comes, but that is far from all:

She got a job selling food in a local store, but found it boring. There seem to be traditional occupations for the middleaged women living alone, the busy and responsible parts of their lives being over. Drink. Gambling. Looking for another husband. A wistful affair or two. That’s about it. Hetty went through a period of, as it were, testing out all these, like hobbies, but tired of them.

Steven Millhauser would take any one of these hobbies and play with it; dead serious, Doris Lessing acknowledges, then moves beyond:

While still earning her small wage as a saleswoman, she began a trade in buying and selling secondhand clothes. She did not have a shop of her own, but bought or begged clothes from householders, and sold these to stalls and the secondhand shops. She adored doing this. It was a passion. She gave up her respectable job and forgot all about her love of trains and travellers. Her room was always full of bright bits of cloth, a dress that had a pattern she fancied and did not want to sell, strips of beading, old furs, embroidery, lace. There were street traders among the people in the flats, but there was something in the way Hetty went about it that lost her friends.

It is as responsive to city possibility as the best of Jane Jacobs, but in that last sentence Lessing clearly keeps her hold on her character as well as on her city:

Neighbours of twenty or thirty years’ standing said she had gone queer, and wished to know her no longer. But she did not mind. She was enjoying herself too much, particularly the moving about the streets with her old perambulator, in which she crammed what she was buying or selling. She liked the gossiping, the bargaining, the wheedling from householders. It was this last which—and she knew this quite well of course—the neighbours objected to. It was the thin edge of the wedge. It was begging, Decent people did not beg. She was no longer decent.

I know of no one since Lawrence with the same ability to make a paragraph seem like such a long journey. And this is this story’s third; there are sixteen pages to follow. Almost every one is as good, and takes us as far from where we thought we were going.

This paragraph and everything else in Lessing show that we can praise London for giving us Doris Lessing almost as much as we must praise Doris Lessing for giving us London. In that destructive element immerse, yes, and the results are nightmares, and prophecies—and old furs, and prams, and the gypsy Hetty is about to become. To say nothing of the cat that comes later, and their friendship and torment, and the rats that eventually devour Hetty’s corpse. One way of praising this wonderful writer and her city is to say that the grim ending will be read by any reader as a kind of triumph.

Football and childhood, fit subjects—perhaps because they are among the few that are left—for American play. Nevertheless, though she is never fun to read and is often tedious, even in a light mood I would rather read Doris Lessing being serious about London. Sooner or later she will give us something like the following, from the stunning Regent’s Park piece that would have made Orwell weep with envy and gratitude, and when she does so she can make us believe that solemnity and ponderousness are indeed the true paths to wonder:

There was this incident when the geraniums had flowered once, and needed to be picked over to induce a second flowering. There were banks of them, covered with dead flower. I myself had resisted the temptation to nip over the railings and deadhead the lot: another had not resisted. With a look of defiant guilt, an elderly man was crouching in the geraniums, hard at work. Leaning on his spade, watching him, was a summer gardener, a long-haired, barefooted, nakedchested youth.

“What’s he doing that for?” said he to me.

“He can’t stand that there won’t be a second flowering,” I said. “I can understand it. I’ve just dead-headed all mine in my own garden.”

“All I’ve got room for is herbs in a pot.”

The elderly man, seeing us watching him, talking about him, probably about to report his crime, looked guiltier than ever. But he furiously continued his work, a man of principle defying society for duty.

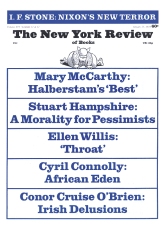

This Issue

January 25, 1973