Tax reform, as George McGovern found out, is about as practical a cause as spelling reform. The income tax has been riddled with exceptions—not loopholes but truckholes, as the economist Joseph Pechman put it—since the day it was born. Every so often Congress feels moved to pass a cynical, regressive “tax reform” law (the 1969 version has been more appropriately nicknamed the “Lawyer’s and Accountant’s Relief Act”). Otherwise nothing happens.

Philip Stern’s book is a denser, more analytical version of The Great Treasury Raid, published in 1964. In both books he makes a clear and overwhelming case for scrapping the deductions, exclusions, exceptions, and rip-offs of the current tax law. In The Great Treasury Raid we learned of the special amendments to the tax codes that are custom-tailored for a particular taxpayer: Louis B. Mayer or Dwight D. Eisenhower, for example. In the new book the list of the specially favored includes the Cafritz Foundation, set up for the Washington hostess/rentier Gwendolyn Cafritz, as well as the Twin Cities Rapid Transit Company, the benefactor of one of former Senator Eugene McCarthy’s less lyrical compositions, his bill “Income Tax Treatment of Certain Losses Sustained in Converting from Street Railway to Bus Operations.”*

The old favorites are here: oil depletion allowances; fast depreciation write-offs; capital gains shelters for what seems like a list of every business that ever picked up a lunch tab for the late Senator Robert S. Kerr. Newfangled variations of the kama sutra of tax avoidance include: the “Mexican vegetable roll-over,” where, for planting tomatoes south of the border, you get the deductions al instante and pay the taxes mañana; actinidia chinensis or the Chinese gooseberry, a tempting fruit that tastes like a combination of rhubarb, pineapple, and guava, and (if you grow it) can be swallowed with liberalized tax accounting. One investment program called “Rent-a-Cow” offers not only tax savings but promises “to add a new and exciting dimension to your life. Just imagine having your own herd of fine quality registered cattle and a big cowboy hat!… Just hop on a jet in New York—we’ll meet you in Tulsa with a twin-engined private plane and within four short hours from your busy city life, you will be in our luxuriant guest lodge, gazing at your own tax-sheltered registered cow herd.”

Such wrongs are as familiar as they are egregious; the interesting question is why they have not been righted. After all, loophole closing offers a means of raising $77 billion without changing the tax rates. Stern offers answers, some obvious, some not so familiar.

The famous complexity of the tax laws, he points out, contributes to the Sisyphean quality of reform: who is to know whether a provision closes one loophole or opens three new ones? Consider this aside in the code: “For the purposes of paragraph (3), an organization described in paragraph (2) shall be deemed to include an organization described in Section 501(c)(4), (5) or (6) which would be described in paragraph (2) if it were an organization described in Section 501(c)(3).” It is through just such needles’ eyes that the rich can lead their camels.

How do loopholes get there in the first place? Often the answer is apparent: special interests give campaign money to the legislators who put them there. Stern advocates reform of election spending as the single best defense against Rent-a-Congressman. Clearly he is right in arguing that campaign funds should be provided through a government subsidy. But that, he recognizes, is only part of the problem. In theory it might be possible to bring public outrage to bear on the dirty work done to the corporate income tax behind the closed doors of congressional committees. The $10 billion or so siphoned off business taxes finds its way into the pockets of the rich or super rich, and most people sense this. The oil depletion allowance has few friends outside the oil industry and the congressmen they own.

Many loopholes in the personal income tax, however, offer no such targets. The most gold-plated of tax exceptions are the ones that seem to protect worthy institutions or their benefactors. Study the tax code and you will find a little something for everyone and a little something else for motherhood and the Red Cross. The elderly get a bonus deduction; the unemployed, disabled, blind, and injured pay no taxes on insurance benefits. Irreproachable activities—charity, homeownership, insurance, health care, education, marriage, employment of welfare mothers—are encouraged under the law. For the few of us who pass through so coarse a sieve without benefiting, there is the ultimate loophole, the standard deduction.

Taxpayers over sixty-five benefit from their special tax exemption, and gifts to Boy’s Town reduce one’s tax liability. But the benefit is scaled to income. Jack Benny’s $750 exemption saves him over $500 in taxes, while a more typical retired taxpayer living in near poverty saves only $100. The federal government matches Nelson Rockefeller’s generosity to the Museum of Modern Art better than two to one—his $100,000 donation reduces his taxes by $70,000. Ten dollars given to MOMA by a schoolteacher will result in a tax reduction of perhaps two or three dollars.

Advertisement

Hence the task of reform is made doubly complicated. First, most taxpayers believe they have a stake in the current system, though in fact they would come out ahead from reform. Then the system of “tax expenditures” corrupts the natural allies of reform: how would drug addiction clinics and civil rights organizations survive if contributions were not deductible? Who would pay the additional interest charges if the City of Newark bonds were no longer tax-free?

One might preserve the structure of the tax system but distribute the saving more equitably by allowing deductions from taxes rather than from income: e.g., for every dollar donation to charity, your tax bill might be reduced a flat twenty-five cents, regardless of your tax bracket. But that would not answer some of the strongest arguments against tax expenditures. Congress, by allowing huge loopholes, Stern argues, would still dole out billions in subsidies for activities that probably should not be subsidized, without even knowing how much it was spending or why.

Stern’s solution is to meet the problem head-on: scrap all the loopholes and reduce tax rates across the board by about two-fifths. This kind of reform would not be confiscatory; the rich would pay at most 40 percent of their incomes in taxes. But the most outrageous perversities of the code would be eliminated: we would have somewhat less complicated tax forms (and somewhat less prosperous accountants), no more hidden subsidies to the League for the Preservation of Spanish-American War Monuments, no more screwy incentives that turn Beverly Hills neurosurgeons into cattle ranchers.

To many economists—as well as to Stern—an even more attractive solution would be to start from scratch with a tax system that could also serve to redistribute income to the very poor. George McGovern’s stillborn demogrant proposal comes close to that description. Instead of a steeply graduated income tax riddled with exceptions, McGovern would have substituted a relatively flat tax schedule and would have made it progressive by per capita rebates—the ill-omened $1,000 welfare checks. Thus a family of three earning $15,000 a year might be liable to a 33 percent tax, but would subtract their $3,000 rebate for a net tax of only $2,000. The same family earning $30,000 would subtract the same $3,000 from a gross obligation of $10,000.

The virtues of the plan are clear enough. A graduated rate structure, even one devoid of loopholes, still makes it worth the taxpayer’s trouble to shift income from good years to bad years and from high bracket adults to low bracket children. Flat rates would make all that finagling pointless. Perhaps best of all, the demogrant would substitute “negative” taxes for welfare payments; the poor would automatically get back more cash than they would pay in. These advantages are so persuasive that many converts to the cause are inclined to attribute public opposition to miserable public relations work—the demogrant would certainly have had a better press if it had been called a tax credit and McGovern had made it clear that the plan could have entailed less bureaucratic paperwork rather than more, and if the cost of the plan had been added up correctly at the beginning.

No PR job, however, can remove some features of the proposal that would strike many voters as unfair. If substantial relief is to be granted to the poor or near-poor, someone must pay. Under the demogrant plan, much of that burden would be assumed by taxpayers who are not rich. Thus a single person making $12,000 would pay $3,000 in taxes—far more than he or she currently pays—while a family of four with the same income might pay nothing. A prosperous, but certainly not rich, childless couple grossing $22,000 a year at present pays 12-15 percent in income taxes; after reform they would pay 24 percent.

Those realignments follow from the technique of using the demogrant rather than graduated tax rates to achieve a progressive system. The big boost to large middle or lower income families would be paid for by single wage earners and the less fertile among the upper middle class.

Of course the reform package could be modified. Children might get smaller demogrants than adults to relieve the trauma for childless taxpayers. Tax rates might be graduated to separate the prosperous from the really rich—perhaps a 50 percent rate above $50,000. But the returns from such modifications diminish rapidly. On the one hand, reform should relieve the burden of the poor, and that requires new revenues: about $30 billion more than is now being spent on welfare would be needed to guarantee a minimum $4,000 for a family of four. On the other hand, reform should simplify the code and keep the rates low enough to discourage elaborate avoidance schemes. The only certain conclusion about federal tax reform is that any detailed proposal carries with it risk for a presidential candidate. Most of the population would benefit from real reform, but it is the rich and well-off in both political parties who best understand their interests.

Advertisement

Stern mentions only in passing the equally appalling distribution of the burden of state and local taxes. The only advantage they seem to have over their federal counterpart is less hypocrisy. While the federal income tax looks progressive, local taxes are just what they seem. Since state and local revenues for the most part depend on sales and property levies, they fall heavily on staples. Thus families earning $4,000-$6,000 a year pay 12 percent of their incomes, while families in the $25,000-$50,000 range pay only 8 percent.

Unlike federal taxes, however, state and local taxes may be headed for reshuffling. In the last two years a number of court decisions have called into question the use of the local property tax to finance public schools. A recent 5-4 Supreme Court ruling rejected any federal constitutional challenge to school finance. But the momentum of property tax reform (supported by some affluent taxpayer groups as well as by public school teachers and organizations representing the poor) may continue.

Under these pressures the California legislature has hit upon a device that resembles a miniature demogrant. They have increased sales taxes to provide greater aid to the poorer school districts and tax relief to property owners. To make these tax changes less regressive, the Democratic legislature inserted a $25 to $45 tax rebate for those who pay rent. This is still small beer; but it at least suggests an excellent way to make taxes more fair without relying on a tough income tax. A sizable per capita refund could make virtually any state’s tax system progressive. These minigrants won’t amount to a thousand dollars, but they could begin to shift the burden of taxes to where it belongs. What is instructive here, however, is not only the fact that a rebate program has started but the special conditions that made it possible: a court decision abolishing local privilege allowed a heavily Democratic legislature to take a small step toward reform. Seriously changing the tax system will require a more risky and honest recognition of the privileges that the system now confers not only on the rich but on the middle class.

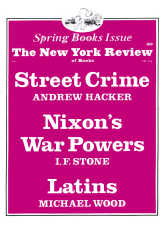

This Issue

April 19, 1973

-

*

These “Certain Losses” had been handled so incompetently by the company’s accountants that an act of Congress was necessary to get back $5 million in federal taxes. ↩