Shelley’s life was short, yet it is nearly impossible to write a short life of Shelley. So many happenings, private and public, affected his work that the biographer’s space begins to run out before the poet has written anything for which his life is worth remembering. And almost all he did and believed needs so much explaining that a mere summary of facts tends to sound like parody. The best short life, Edmund Blunden’s of 1946,1 was so careful not to blame anybody that its total effect is unlifelike, while the full-scale biographies—all double-deckers—are now between thirty-five and ninety years old. Of these last, Newman Ivey White’s2 is indispensable as a kind of memory bank of known sources, but in its abridged form3 it has a distinctly prewar flavor. Richard Holmes’s new single-volume biography is a very good book, compulsively readable, which really does make contemporary sense of Shelley and his friends.

Holmes’s introduction somewhat exaggerates the effect of the revolution in Shelley studies that has taken place in recent years. It is rash to say that, except for Yeats and Carl Grabo, “there is virtually no literary criticism or critical commentary which is worth reading before 1945.” Hungerford? Carlos Baker? K. N. Cameron? As early as 1924 Olwen Ward Campbell, almost in Holmes’s own words, was ridiculing the way Shelley had been “so tricked up in the frills and furbelows of sentimental scribblers…that many people think of him as a writer of enchanting lyrics, who was, in other respects, at best, one of God’s own fools.” Victorian opinion is generally squeezed very thin nowadays between Early Reception and Twentieth Century Judgment, but even in the days of idolatry there were true critics.

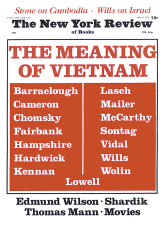

However, the perspective has certainly changed. For “the image of the gentle, suffering poet” Holmes substitutes “a darker and more earthly, crueller and more capable figure,” moving “through a bizarre though sometimes astonishingly beautiful landscape.” Holmes’s Shelley is in fact noticeably closer to the diabolically knowing innocent of David Levine’s cartoon on this page than to the portrait which Amelia Curran and her copyists steadily made less and less distinguishable from that of Beatrice Cenci (witness Easton’s newly found version of the Curran painting in Keats-Shelley Memorial Bulletin 23, 1972).

There is a little new material, but the book’s originality is essentially in its interpretations. Shelley the political animal is taken seriously: he was a fighter (as Kenneth Neill Cameron was the first to insist), and the Irish campaigns, in which, to Godwin’s horror, he tried by speeches and pamphlets to start a movement for the independence of Ireland, are treated without the caricature they usually invite. Since Leslie Stephen it has been axiomatic that Queen Mab is Godwin’s Political Justice versified, but Holmes shows that the poem owes relatively little directly to Godwin. I think that anyone who tries to annotate Queen Mab will agree.

The impulse toward violence in Shelley’s make-up is very interestingly traced, as is its contribution to “the continuing strength of the gothic and grotesque inheritance” in his later poetry. Shelley enjoyed scaring people; with children this was just a thrilling game, but he liked giving adults the horrors, too, including himself. Perhaps Holmes does not make enough of the practical-joker side of Shelley’s nature, which delighted in the adoption of “pretend” roles; if his imagination was often aggressive, driving Claire Clairmont into hysterics and weaving ghosts and Furies into his verse, it could also express itself in poems of wit and fun such as the Gisborne Letter and “The Cloud.” Judith Chernaik’s coolly intelligent study of the shorter poems, The Lyrics of Shelley (Case Western Reserve University, 1972), evidently appeared in time to help the biographer with new texts but not in time to make a convert of him. In reacting against Victorian taste, he writes off some of the lyrics too impatiently.

Locality meant a great deal to a poet who wrote mainly out-of-doors. The effect on Wordsworth of going abroad was to make him protect his native idiom more jealously, whereas for Shelley crossing the Alps was like adopting a new and more lucid poetic language of which the various places he settled in were different dialects. He had a sort of tropism toward beauty spots, bizarre or otherwise—the Lakes, Lynmouth, the Welsh mountains, the Thames valley (as it then was, alas), the Alps, Este, Florence, Lerici (Livorno was the exception, where human company was preferred to place)—and the special quality of each spot formed part of the meaning of what he wrote there. Holmes has visited many of Shelley’s haunts and is often strikingly good at displaying, without rhapsody, the connection between the place and the “interior landscape” its atmosphere had suggested.

Advertisement

The strange appeal of Pisa, where Shelley made his longest stays in Italy, is particularly well explained. The flowering ruins of the Roman Baths where much of Prometheus Unbound was written were both the inspiration and the symbol of the drama. “Power and imperialism were destroyed. The forces of human love and freedom, and of Nature, which [Shelley] regarded as allies, did in the end reassert themselves, just as the innocent and white blossoms of the laurustinus covered over the desolation of Caracalla.” Most suggestively, Holmes identifies a particular configuration of landscape that always attracted Shelley, an enclosure backed by hills, opening into a single channeling vista. “His houses were, for choice, each one an ultimate retreat in which he seemed to be waiting, back to the wall, for the inevitable pursuer…inexorably advancing through the only route that is not barred. Once again, this is a central image in the mature poetry.”

There are a few topographical confusions. The Shelley children’s “secret and illicit expedition to Strood, travelling cross-country” is made to sound very formidable, whereas it was every inch of a mile over their next-door neighbor’s fields (there must be something mirage-like about this neighboring estate: the second volume of Cameron’s Shelley and His Circle had Shelley take his girl friend to Strood on a moonlight stroll of fifty miles). If the Shelleys had gone east from Llangollen they would have fetched up by the North Sea instead of the Welsh coast (and Harriet said they never went to Llangollen, anyway). The voyage celebrated in “The Boat on the Serchio” must have been upstream to Bientina on May 31, 1821, under the old moon, not downsteam to the estuary. But such small confusions do not spoil the over-all impression.

For this reader, the book’s one inexplicable lapse is the explanation offered for the “Hoppner scandal” and the parentage of Shelley’s “Neapolitan ward.” It is well known that while in Naples Shelley registered a daughter, Elena Adelaide, as having been born to himself and Mary on December 27, 1818. Mary Shelley cannot have been her mother; and White’s solution to the problem was that Shelley had adopted an Italian foundling, illegally. Holmes argues that Shelley fathered Elena on the thirty-year-old nursemaid, Elise. The author’s confidence in this theory is hard to understand. If Elena’s official birth date is correct (it may not be), she must have been conceived early in April 1818, so Elise was at least six months pregnant when her attachment to another servant, Paolo Foggi, became common knowledge. “Elise was therefore pregnant and had to be married off urgently,” we are told.

But the urgency of a marriage in January is not apparent when the bride has already given birth in December—especially as it legalized Paolo’s custody of a child that Shelley meant to bring up himself. Paolo would have demanded a substantial dowry before marrying under such circumstances; without this demand—even with it—the Shelleys were amazing hypocrites to keep calling the poor fellow “a great rascal,” “a most superlative rascal,” when he must have been one of the most cooperative manservants since Leporello.

Mary Shelley’s story is in fact perfectly credible (and she would never have offered it to Mrs. Hoppner’s malicious scrutiny if it were not). She wrote to Mrs. Hoppner, with whom they had stayed in Venice, “You well know that [Elise] formed an attachment with Paolo when we proceeded to Rome.” Mrs. Hoppner could know nothing of what happened when the Shelleys proceeded to Rome, unless indeed she had seen Elise and Paolo forming an attachment inside the coach while the farewells were being said. Mary’s sentence evidently means: “You know quite well that when we left you an attachment existed between Elise and Paolo.” Mary was writing in an overwrought state, “so that I can hardly form the letters,” she said.

So the attachment was plain to all by the end of October 1818; no doubt it was why Elise wanted to leave Byron’s service and rejoin the Shelleys. Elise and Paolo could not have met before September 24, but they certainly met six days later when the whole party came together at Este, and Paolo (a fast worker) had most of October in which to improve the acquaintance. Elise could therefore have been up to three months pregnant by mid-January 1819, and so at maximum risk of a miscarriage.

Mary’s letter continued: “…she was ill, we sent for a doctor who said there was danger of a miscarriage. I would not turn the girl on the world without in some degree binding her to this man. We had them married”—on or just before January 23. Elise had to go, but after failing to shake her infatuation, Mary insisted on Paolo’s marrying her in order to protect her from exploitation. True, no more is heard of Elise’s baby, due in July 1819. But Mary did not say the danger of miscarriage was averted. Four years later Mary herself was “threatened with a miscarriage”; the threat passed, but she did miscarry all the same.

Advertisement

Holmes’s supplementary claim that Shelley and Claire Clairmont were lovers at Este (and that Claire had a miscarriage on the very day of Elena Adelaide’s birth) is another matter; but no account is taken of the lines which Shelley scribbled under the walls of Este Castle to express his love and longing for Mary while they were separated:

Mary dear, come to me soon,

I am not well whilst thou art far;

As sunset to the spherèd moon,

As twilight to the western star,

Thou, belovèd, art to me—[Hutchinson, Complete Poetical Works, Page 553]

The most disturbing feature of the Elise/Shelley theory is its psychological incongruity, since Holmes shows so much understanding elsewhere of all the personalities concerned. But nothing prepares the reader for the revelation that Shelley was liable (like Byron at one time) to assault his domestic staff at the drop of an apron, nor is the least flicker of sexual interest between Shelley and Elise noticed either before or after this one irresistible encounter.

On the contrary, as Holmes’s book itself shows, several attributes had to coincide in any woman for Shelley’s sexual feeling to be aroused: (a) some matching refinement of mental life, or some ideological affinity, real or supposed (Shelley was a “symmetrical” lover—one who sought his own likeness in the loved one); (b) beauty; (c) mutuality; (d) difficulty of access. Not one is established here. This undermines confidence in the narrative to follow. If Shelley is so meaninglessly unpredictable, why take his motivations seriously?

There is, of course, a passage in Epipsychidion (on which Holmes reserves judgment) supposed to allegorize a visit to a prostitute when Shelley was eighteen or nineteen (how exotic those Oxford trollops were in 1810!). There Shelley describes his recognition of ideal Love, followed immediately by that of “One, whose voice was venomed melody”; and only then does he begin listing the various loves he has known in the flesh (“In many mortal forms I rashly sought / The shadow of that I dol of my thought…”). So surely the siren with the husky voice is Love’s false counterpart, Death, and Holmes is right in connecting her with the figure of Plague in The Revolt of Islam. Her closest parallel, however, is Morte in Shelley’s Italian allegory Una Favola, which Holmes does not discuss.

But it would be quite wrong to let a single section, merely because it excites the reviewer to a sacred rage, detract from the excellence of the whole. This is a fascinating and valuable book.

This Issue

June 12, 1975