The history of blacks is complicated, fragmented, disturbing to contemplate, not a neat trail of challenges met or of felled trees blocking the path to the mountain top. When writing on black life, whites have often been unwelcome, usually called upon to give witness or hauled in as the accused. Feverish protection of cultural territory has bred a timidity among whites, whose hesitation is not quite owing to liberal guilt, but rather to the exhaustion white Americans have been feeling for some time. They suffer the ache of feeling overwhelmed, faced as they are with the difficulties of having a tradition, in regard to blacks, that discourages close scrutiny. Blacks clamored to be heard and then they spewed accusations. Some whites and blacks probably had the same thoughts: They will never understand. Do we?

Black leaders with faces as familiar as movie stars now stand before a dwindling number of microphones in postures of defiance and righteous resolve that seem archaic. The gestures and rhetoric of the self-absorbed bureaucracy, of the will-less government, show how serious interest in the black situation has waned. Statistics suffice to reaffirm the faith in costly and well-meant progress. Popular television culture has promoted the silky assurances of sentimentality about black history. Advertisements and situation comedies have announced the great reconciliation: we survived the nightmare of hot city summers.

This cultural climate has much to do with the appearance of Certain People, Stephen Birmingham’s poorly conceived and clumsily presented attempt to describe America’s black elite. The book has already received much unfavorable notice. Perhaps we should have seen it coming: The Right People, The Right Places, “Our Crowd“—Birmingham’s previous titles suggest a lamentable hobby. Recently, Vogue carried a Birmingham article on black fashion queens, and its giddy approval of highly refined brown sugar governs most of Certain People. Militancy as a style among visible blacks has subsided, creating for writers like Birmingham a new kind of accessibility and coverage. The niceness of the race is redeemed. Andy goes on the red clay Georgia trail; Andy goes to Washington; Andy goes for the heads of Her Majesty’s diplomats. This is the year of the Bionic Black, and porkchop nationalists have lost prestige.

Many of the nervous themes in Stephen Birmingham’s study could be real subjects. But, with him, they are little more than the same old tap dance. The redundant quality of the book betrays a mind utterly lacking in sophistication and imagination. No doubt Certain People will feed the vanity of those characters listed in the index. It is a work destined for display in some homes, on the mahogany coffee table between the Illustrated London News yearbook and a large piece of Steuben glass. Yet, although it is easy to ridicule and dismiss many of Birmingham’s galling pages, he has, somehow, hit a nerve. The subject of black success is curiously embarrassing. There has always been, in black communities, a desire to measure advancement, to claim one black person’s achievement as a sign of accomplishment for the many. But what was once uncommon—a black surgeon, a black judge—only a few years ago, is now expected, the language of success obscuring the slogans for equality and integration and opportunity.

In the black autobiographical tradition of James Weldon Johnson and Richard Wright, we have numerous accounts of a black’s journey that are full of serious meaning. But in more recent works this has been lost in a torrent of testimonial clauses, self-justifying sentences. Only Angela Davis’s reticent political autobiography has retained the modesty and passion of the personal odyssey as a form of social thinking. But it is hard now to live her sort of life. Every utterance, display, and monologue of a black are to be made in the vein of self-congratulatory symbolism. Everyone wants to tell his story, as if the audience were not restless for a long intermission.

Birmingham makes much of Charlotte Hawkins Brown, who founded the Palmer Memorial Institute in Sedalia, North Carolina, a preparatory school for the children of affluent black families. The school was exclusive and placed its students in good colleges, but “Doctor” Brown is scarcely the enduring figure in black educational history that Birmingham takes her to be. In fact she made no significant contribution to styles of black pride, “was an unabashed snob,” wiping the lipstick from the mouths of girls as they entered chapel, disapproving of her niece’s marriage to Nat King Cole. Her book on etiquette, The Correct Thing—To Do, To Say, To Wear, is a provincial, mean-spirited guide. Timothy Titcomb’s Letters to Young People and Emily Post’s tips to anybody with enough change to buy a paperback book do not give advice, as Charlotte Brown does, on how to open an office door, how to “call on” one’s inferiors, nor do they contain evasive paragraphs on hair grooming. Inner disadvantage shows: “Don’t go where you’re not wanted.” There is something peculiar about Charlotte Brown’s rules of good behavior, about the absence of any discussion of skin color in her book. Birmingham senses this, but since he sees nothing of the pain of segregation behind its high tone, he cannot reveal its interest as a document of black social movement.

Advertisement

Moreover, many American cities have had their excellent all-black schools, such as the Atlanta University Laboratory High School, and these cities have their graduates of those schools. Where else could good black teachers and students go? No one should be surprised that, given the racist structure of American society, regional and class prejudices developed among blacks in their corraled circumstances. Yet to Birmingham this is news. There may have been the rivalry between Charlotte Brown and Mary McLeod Bethune that Birmingham claims existed. Mary Bethune may have been regarded as a “big fat black woman,” as my mother said, too dramatic and too proud of knowing Eleanor Roosevelt; Booker T. Washington may have been looked down upon. But these are ephemeral attitudes since the founding of Bethune-Cookman and of Tuskeegee was not a small matter and meant, simply, increased educational opportunity.

That Birmingham thinks he has discovered something new in the discord among blacks is a sign of his naïveté. Collective action has always been the ascendant tactic and rancor is not easily admitted. But nothing erases such rancor—or should. Unfortunately, Birmingham has overlooked a critical contradiction: Western culture is all Black Americans have had and yet blacks are viciously mistreated by this culture. “Refinement” is simply the unsatisfactory imitation practiced by the brutally dispossessed.

Birmingham’s narrow interpretation results in many ill-considered statements. Many educated blacks were former students of the Palmer Memorial Institute, but he distorts historical reality to give the impression that the Niagara Movement and the NAACP owed their beginnings to Charlotte Brown’s influence on “many of her…elite-minded students.” Birmingham characterizes the NAACP as a restricted, removed organization and notes the sneers of “less affluent” blacks. This was one of the paralyzing myths of the last decade when impatience with moderate groups was often voiced. But it was something of a misrepresentation. Several of the landmark civil rights cases could not have been won without the dogged assistance of the NAACP. And although Birmingham mentions that Madame C.J. Walker, the hair-cream tycoon, sent her heirs to Palmer, he typically says nothing about the strong support she gave to the Harlem Renaissance, a period of vital artistic activity in modern black culture.

The finishing school obsession with speech, clothes, manners, connections, and home addresses is one Birmingham shares. If the families he interviewed were eager to tell him the price of everything, to show him the Jacuzzi whirlpool baths, he was equally eager to record such items. They are, Birmingham assures us, the mark of the parvenu. But descriptions of Harry Belafonte’s bar, of Motown Record wizard Berry Gordy and his fur walls, do not so much illustrate the gaps in the black community as they do the color blind tendency of the nouveau riche to flaunt their goods, the narcissism that has seized American consumer society.

John H. Johnson and his mother, “Miz Gert,” are the sovereigns of the private company that publishes Ebony, Jet, Black World, and other fish-wrapper magazines. They manufacture piss-chic cosmetics also. George Johnson (no relation) runs the firm that markets Afro Sheen, Ultra Sheen, and other products that make one very clean. Rags to riches stories; up from slavery, in the material sense. These black executives want to be examples for black children in the streets. But money, in America, is not a matter of display or security, but of power. The last name on Fortune magazine’s all-white list probably has influence that the Johnsons could never conceive of. Birmingham acknowledges the discrepancy between economic success and real power among blacks, but he fails to see that it is a discrepancy central to the relation of blacks to American society. Instead he concentrates on the competition between the two-Johnsons, seeing this competition as a serious obstacle to the solid establishment of a black power base.

Mismanagement, market restrictions, lack of capital, and the opposition of white businesses describe the fates of many black business establishments. Though small, such businesses are not at all new. It is disappointing that Birmingham does not mention the “League for Fair Play” or the “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” movements of the 1920s and 1930s in his quick history of black businesses. Programs of picketing and boycott often ended in incidents like the Harlem riot of 1935. Black businesses compete, but they have always had a common enemy. While Birmingham mentions some black enterprises that have dealt with a white clientele in the segregated past, he overlooks the many thousands of black-owned businesses that served the black community and the jobs and opportunities for advancement they provided during periods of general economic retrenchment and discrimination. W.E.B. DuBois: “It is a paradox of the times that young men and women from some of the best Negro families of the city…have actually to go South to get work, if they wish to be aught but chambermaids and bootblacks” (The Philadelphia Negro, 1899). From 1888 to 1934 at least 134 banks were founded by blacks. By 1928 some eighty-two of these had failed.

Advertisement

The fortunes amassed by blacks, the development of black businesses—to the conventional mind these, not failure, are what matter. Birmingham perversely gives power to hairdressers, barbers, contractors. Early black caterers, he claims, made virtual slaves out of the cream of Philadelphia society. Yet could any of these struggling blacks have been able to leave such service jobs to become like the Biddles?

Quick tours: rooms of honey, beige, gold, caramel, earth brown. “We wanted colors that would match our skin tones,” Mrs. John Johnson says. A $250,000 extension of the self. Mary Hartman would go irretrievably insane in the Johnsons’ kitchen: six sinks, three dishwashers, two stoves, four refrigerators, a charcoal pit. But there is also a large Picasso in the dining room. Miz Gert talks endlessly about her son: “I’m the one, I’m the one that did it!” There appears to be much paranoid vanity under the greasy, corn-rolled braid. We shall overcompensate after getting over. Forget overcoming.

“Syphaxes speak only to Wormleys, and Wormleys speak only to Cobbs,” Birmingham writes after his visit to Washington, DC. No doubt certain families speak only to Kunta Kinte. An annoying feature of this study is Birmingham’s assumption that aristocracy, for blacks, depends largely on histories of miscegenation. Many blacks can claim relation to white families of good blood. Often connections come from incidents of rape, illegitimacy. A familiar if little-publicized scene: being shown a photoengraving of South Carolina’s Civil War governor and being told by “Great-Grandmommy” that he is still somewhere in one’s veins. Should there be an en masse effort to gate-crash the DAR? After all, most black families haven’t been “in trade” since 1619. Descent from Martha Custis Washington, slave owners, or the nephews of high-minded abolitionist dowagers does not grant one any special rights or privileges in a racist society. There is little solace in the punishing ironies of most black family histories. A bus driver or a sheriff does not care if you are in the line of El Cid when he makes you take a seat in the back of a bus or unleashes snarling dogs on your children. John G. Van Deusen’s The Black Man in White America (1944): “Even a congressman, Arthur W. Mitchell, Negro member from Illinois, was not permitted to remain in his Pullman after it entered the state of Arkansas.”

Variations of shade and consequent scales of status are bitterly common in black literature. The reasons for such fastidious attention are obvious. The dispensations of one’s time are tyrannical.

I attended the Fifth Avenue Baptist Church and shared in a beautifully prepared Armistice Day Service. I happened to be the only lost sheep of Ham in that body and yet so much of the blood of Japheth courses through my veins that the natural eye would hardly be able to pick me out.

—lines from Sterling N. Brown’s autobiographical pamphlet

Yet this professor’s son, the poet and scholar, also wrote quite different and truer books, from Southern Road (1932) to What the Negro Wants (1948), showing the changes accomplished from generation to generation. An externally imposed self-loathing is at the root of the emphasis on skin color. The notion of “white looks” being better, of light skin being an advantage—it would be hard to find a more thoroughly American problem of “image.” The proper rebuke is in Claude McKay’s novel about the cabaret jazzers, Home to Harlem, published in 1928:

‘Yaler, it ‘pears to me that youse just a nacherally-born story-teller. You really spec’s me to believe youse been associating with the muckty-mucks of The Race? Gwan with you. You’ll be telling me next you done speaks with Charlie Chaplin and John D. Rockefeller.

The archives we carry within us can always have their uses. But retelling family folklore is like counting through a chest of debased coins. None of the family histories in this book is of any lasting interest. Reading about the Old Guard black families in Chicago, in Atlanta, in Washington, and in New York is a tedious chore, with their repetitious lists of connections, marriages, schools, degrees, occupations, every detail unvaried from house to house. Perhaps this is the betrayal anecdote meets on the page. For the pride and standards of these families we are glad, but Birmingham does not do justice to their isolated destinies, the insular rituals among them. Perhaps the importance of these families has always been illusory. It is doubtful whether the clubs and fraternities and vacation spots mean anything to the large black population. Would a black child in a slum rather marry into one of these families than be Muhammad Ali? Class is self-perpetuating only for those who depend on it as a sort of narcotic.

One’s own kind, “like us”—these attitudes are the result of pluralism and their meanings are, by now, entirely personal. Birmingham makes much of the various black groups but no one else does, not even the members. The North-easterners: “It’s getting browner,” my mother said after a party in Boston. The Links: Birmingham discusses the jealousy between the chapters of this women’s club but my mother, a member, had never heard anything like that. “Jive.” Bridge clubs: we all know niggers loves to toss cards, honey, and many of us have childhood memories of wonderful food and late night mischief while our parents played trump after trump, the television showing us blacks being arrested. That the majority of blacks could attend only black colleges must reduce surprise at the cohesiveness found among members of black fraternities and sororities. Greeks have always invested a strange kind of energy in rivalry and the children of former members have always had a better chance of entrance than those whose parents were not. None of this is peculiar to black college groups.

Another weird black group: Jack ‘n’ Jill. The mention of the name causes a sinking of the heart. The right sort of children were herded together to meet others of their kind. Chaperoned Halloween and Christmas parties in basements of teakwood bars and green walls. Vaselined adolescents swilling sweet punch, squeaking in tight, polished shoes, struggling to do the “Tighten-up” as the better coordinated laughed. Debutante parties: my sisters weeped on and spoiled make-up. Oak Bluffs and Fox Lake: summer seasons of sticky orange Nehi soda, waiting to get back to one’s friends playing with a tire in the alley. On the beach at Sag Harbor: “Will you have your martini before or after the watermelon?” And the ballet lessons, the piano recitals….

Birmingham does not see where such groups fit, how peripheral they can be; they were not necessarily always the goal of upwardly mobile blacks. They mean nothing in view of the real issues in American social history. One’s great-grandfather may have had a passion for Milton, but he still had to hide under porches in order to escape a “neck-tie” party. The stories of grandfathers: drills for the army reserve on Ivy League grounds, the four blacks at the rear of the squadron. Birmingham has reduced and slandered wholly personal chronicles for the sake of pernicious myth.

After slavery was abolished,” Birmingham writes, “the same sort of situation prevailed. If there was education in a Southern black family, it was usually on the mother’s side.” Showing his ignorance of slave society by such fatuous writing, he does not move us beyond E. Franklin Frazier’s serious but ambivalent survey of the black bourgeoisie. Recent excavation and information have given an urgent, contemporary tone to black history; events barely cross the news-wires before they seem locked in a popular, historical tableau. Both black and white writers sense they will be greeted as false prophets at history’s dustbin, and strain to avoid such a fate. But St. Clair Drake’s and Horace R. Cayton’s Black Metropolis, published in 1945, is, sadly, unsurpassed.

Upper-class Negroes are not, as some superficial observers might imagine, pining to be white, or to associate with whites socially. They are almost completely absorbed in the social ritual and in the struggle to “get ahead.” Both these goals are inextricably bound up with “advancing the Race,” and with civic leadership. In actuality, the Negro upper-class way of life is a substitute for complete integration into the general American society, but it has compensations of its own which allow individuals to gain social stability and inner satisfaction, despite conditions in the Black Ghetto and their rejection by white America.

The war of impulses, the suspicion of the system and its values continue, but it is difficult, for some of us, to imagine segregation as a permanent life-theme. Psychological damage is the only real heirloom in black families. From Richard Wright’s introduction to Black Metropolis: “That there is something wrong here only fools would deny.” Birmingham’s work must be counted as yet another indignity.

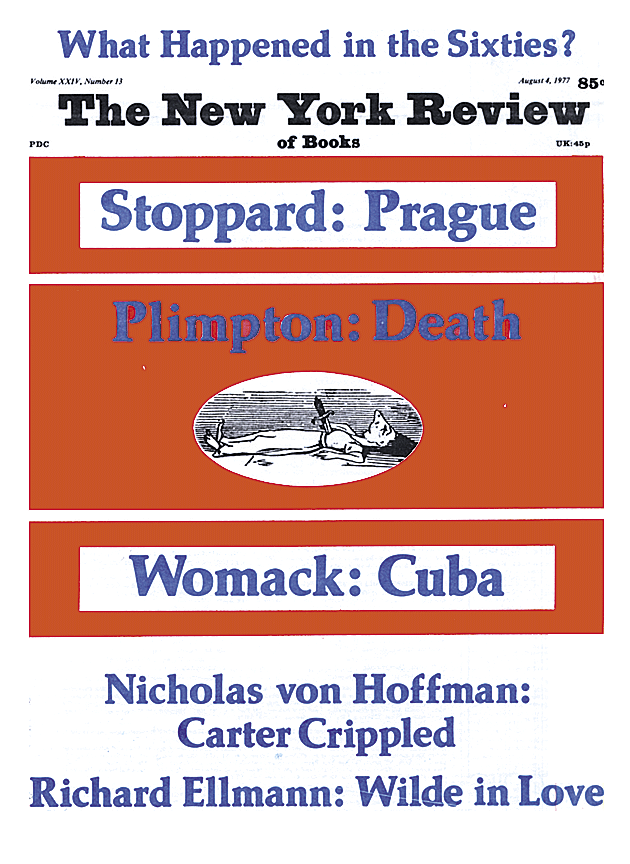

This Issue

August 4, 1977