On the loveliest of winter mornings in New York City, un enfant de siècle, nearly fifty years old, is walking with a brisk, almost military, purposefulness down Broadway. The clean cold air and the pale blue sky are the best the city has to offer and all the millions who have never held a golf club, ridden a horse, or skied in the mountains have reason to be thankful.

He, Ackermann, moves along with a sort of athleticism of the brain, a refreshing jog of ideas, and a bit of concern for the future of his lungs and arteries. Health is not always easy to maintain because he is living in the gold of his middle age. Cream sauces at the banquet table, the velvet of sofas on Park Avenue, the roller-coaster elevators in the Waldorf Towers—and Washington, Washington itself. Nevertheless he is impressive as he goes down the blowsy street like a commandant of the regiment with a burning smile, posture erect, medals gleaming. And if his pace is interrupted by the arrogant fleetness of truant youth or the stumbles of shabby old people—no matter.

What is the purpose of your life, Ackermann?

Ah, the parts do not describe the whole, dear interviewer. This life at the desk, in the lecture hall and the magazines, the meetings, the opinions, groupings, alliances, friends and enemies—enemies, there’s always that.

Ackermann is a teacher, a writer, and a critic. Indeed a critic, one of the unfraternal nest of barn owls, men and women, similar, some of the wounded say, to a species known as “nightjars” for their confident, high-pitched cries.

There is more to Ackermann than that. He is a neoconservative, something of a hero of the counterrevolution; and handsome as a minor film star with his strong head and coarse curly hair.

He is nearing West 72nd Street. Every rock and rill is known to him. Here lie the cataracts, the grazing field, the mountainous landscape of his political passage. He has roamed these woods as a boy in the West 90s, lived until a few years ago on Riverside Drive amid the azaleas and forsythia and the speeding of drunken powerboats on the Hudson and the heraldic neon markings of the castles of the Palisades. Here are the shards of his youthful liberal clichés, the chopped-off carrot tops of his adversary assumptions, the shriveled balloons of his generation’s elated predictions of capitalist catastrophe.

Ackermann is writing a memoir, a political autobiography full of messages as blunt and demanding as those of the prophets to the house of Ahab. And yet he wishes it to be here and there nostalgic and poetical since he is first and last a student of literature and, like a Slavophile of the last century, mystical in his native fervors, his passionate, dream-tossed Americanism.

He nears the Hotel Ansonia, a declining Parisian beauty, sun-spangled on the upper windows. And this he knows also from his violin lessons, this bit of old New York, as we might call the building’s eighty years of solfeggios in the mornings, tenors assaulting the crystal chandeliers with their menacing exhalations, Steinways decorated with the framed, incomparable faces, saying, “To my young competitor with the good wishes of Josef Hofmann,” and “All the best, Elisabeth Rethberg.”

Outside the Fairway Market, plump oranges and pink-cheeked grapefruit in the bins, and as he stands in the line to buy an apple he feels the breath of opinion on his back.

The trouble is.

The death penalty’s too good for.

I’m telling you.

They ought to.

Luminous day. In the gutters a litter of appeals for fortune telling, massage, keep missiles out of Europe, hands off Nicaragua. Not a person on the street, not a vendor, not a West Side woman protesting gentrification in the midst of the resistant stasis of Broadway—not a one who didn’t want to run the country.

Little new, little new. This world was a dusty old pocket with the zipper stuck. A field of corn, a ranch in the hills, a flagpole on the lawn, a barbecue were as alien as a Wampanoag Indian. As who knew better than he who had walked the trail back home from his new co-op in the East 80s, a cool and courteous dwelling that had an effect upon Ackermann and his wife like that of having gone on a successful diet.

He is on the West Side to honor a family duty. In no way a martyrdom. Family feeling was alive in Ackermann’s soul and there was hardly a day that some stray motion or thought did not cause him to grieve for his mother and father. His father with his troubled heart died when he was sixty-two years old and three years later, without warning, his mother collapsed with a stroke that took her away in three days. For them Ackermann had gone to the University of Chicago when he was fifteen and, looking back, he believed it was for them that he once imagined himself a novelist who would honor their superb reasonableness, touched with melancholy, which illuminated the boredom of his adolescence.

Advertisement

Here he is in the apartment of his sister, Miriam, the last of his parents’ offering to fortune, Ackermann’s flesh and blood, if “nothing in common.” With a filial sympathy he approaches his sister’s presence, the predictable rush of her being. And certainly everything is predictable, in tune. Miriam is nicely recovering from pneumonia, wearily complaining of the country’s health care, the cost of things, the hot summer just past, the determination of the building’s owner to evict the old rent-controlled tenants.

Ackermann: Tenants are not rent-controlled. Apartments are rent-controlled.

Miriam is propped up in a very large lascivious bed, topped with bolsters, large pillows, and small pillows ready for the accommodation of her unruly dreams. Her thick, wavy “Ackermann” hair falls about her shoulders. Cigarettes fill the night tables on the left and the right, tables cluttered with wine glasses, a bottle here and there, a stray saucer, as if at the end of a meal. A week’s pile of The New York Times lies nearby on the floor. The room retains the sweetish scent of the fever and flush of pneumonia—or perhaps it is the fume of a large box of chocolates on the bureau.

Some forbearance is necessary on Ackermann’s part and little, if any, on Miriam’s since she does not take in much about her brother’s last years. His travels, consultations, his dominating position on two conservative foundations, his acquaintance with the president, his books and articles. In Miriam’s view everyone in New York is writing, being consulted, going places, meeting famous people. She herself has worked on television political documentaries and has spoken more than once with generals of the Vietnam War, officials of the NAACP, leaders of the women’s movement, brain surgeons, sociologists from Harvard. In her view, the city is the fast track for one and all.

The one vexing advantage of her brother’s life had taken place long ago. Their father, a professor of geography at Queens College, had taken the teenage son to all sorts of places: to Africa, Portugal, and South America. This Miriam saw as a deprivation to herself since the places appeared in her documentaries and it might have been useful for her to say: No, no, in Upper Volta French is spoken. We’ll need translators on that spot. Even now she will shake her head and say: The third world didn’t rub off on you.

Ackermann: Miriam, there is no such thing as the third world.

Miriam is haphazard indeed. Her brother, in kindly if sometimes fatigued reflection, sees her as a burrowing, frizzy-haired troglodyte of the 1940s. She is late for every appointment, wandering in attention, has lost out at the TV station, and as for ideas, those veins in the very rock of character, she is blithely fond of Castro, the Sandinistas, gays, blacks, welfare clients, and as routinely and naturally as applying lipstick and mascara in the morning. To all these matters she gives a distracted nod, as if voting in a large assembly.

For the rest, her main project, as she calls it, is her sluggish affair with a married man whom she doesn’t much like and who does not appear to be pressingly keen on her. She is, of course, long separated from her husband, a man of great sentimentality who maintains her in her scattered independence.

The phone rings and Miriam raises her hand like a traffic cop. Let it go. It is either Ethel or Harry or Duane or Jimmy or Joan.

Miriam’s life is a large canvas of nymphs and satyrs, matrons and courtiers, and her conversation about them is an innocent, diffused commentary like something coming through earphones.

A. is having her first child at forty-one, not married. Amniocentesis OK. A girl.

B. came home one night and she had packed all his underwear in a large army footlocker and put a three-pound padlock on it.

C., a Bolivian, has vanished from his post at the UN, is planning to take a new name and set himself up as a dress designer.

Now she begins to cry and at the same time to drink from a cold cup of coffee beside the bed. Her children, off on their own, great kids and a real mess. With an almost scriptural regularity she checks off the ordained rhythms of her life. Feckless children, uncertain income, boring husband, and recalcitrant lover. And yet large plants by the windows flourish in their dry soil, copper pans choose to gleam in the slanting sunlight of the kitchen, the framed Ben Shahn “Ban the Bomb” poster year by passing year comes to look quite valuable.

Advertisement

A blue bowl filled with lemons, sheaves of wheat on the wallpaper. Around the disorderly Miriam there is an eruption of fertility, the sensuality of a feathered slipper, a band of satin. She is in her nest—husband gone, children fled, and her domain is perfume, cosmetics, and mirrors, closets and drawers rich with stockings, bathing suits, a bit of fur.

Miriam rises in a spring-flowered robe from her amorous bed. She has the family beauty and her large eyes are now as clear as water. She is ready to be very busy. Busy is sometimes a sigh and then again a mystery, a secret, and the urban clocks tick away fatefully.

At the door she says: This building is not falling down. It’s worth a fortune. All he wants is profit.

Ackermann decides against rebuttal and for a moment the two of them brother and sister, are framed by the open oak door and brass knocker, beneath the Corinthian leaves of the handsome, not quite tidy, hallway. With their strong noses and arched brows they might be Venetians of the sixteenth century.

Ackermann is out on the street once more, roaming in the globe of his times. A large and challenging cosmos it is with catastrophic Bolshevik birds of the north flying in formation from the snow-clad top of the world; and the rash, overheated mosquito continent of Central America; and the beleaguered orange groves of Israel, the ever-brooding and breeding Palestinians, and here and there small populations fat with conceit; and the echoing Middle West, East Coast, South and Middle Atlantic. To hold positions is to fight a duel at every dawn and not with some rubberbooted terrorist creeping out of the forest but with a bright-eyed Vulcan thundering on TV. Oh, ye hypocrites.

In the distance he sees a terrible figure of solitude approaching him. It is like a celestial accident dispersing the statistics and probabilities of existence in a city of almost twelve million. Five minutes, two minutes, two seconds, a happy crossing to the other side and this unwelcome apparition coming toward him would himself be only a statistic. No escape from the distracted ally in the battle, a fair-faced thinker, wrinkled and yet glittering with an inner fire fed by the kindling of notions.

His name is A. Stanford Hamilton, the A standing for Alexander. No volatile financial or political genes remained from the two-hundred years’ passage through many respectable blood streams. This Hamilton is in a worn tweed coat and red muffler. With his thin eagle nose, his inward smile, skin white as bread, he is a battered icon among the sallow citizens from hot islands or from the cold huts of Baltic ports. His is a story of the failed bourgeoisie, of polite Anglo-Saxon clapboard mansions fallen from hope, of ancestral oaks of a depressing unfruitfulness.

Hamilton has written a few things soon forgotten. Short they were, book reviews and essays whose existence on earth ruled his future like a bad omen in a fairy tale. He could go neither forward nor backward nor in another direction. Sometimes, as Ackermann has reason to know, a hasty, hortatory, satiric sketch reared up and was struck down by silence. These messages lay in the files, in the drawers of small magazines, lay there gathering dust because the editor could not undertake the refusal of a lost friend.

Hamilton appears at conservative meetings and panel discussions and in the open forums sits in the front rows with his crooked, knowing smile and gives off somehow the intense glitter of his roiling disconnections. A treasured, carefully reared little boy, grown old, cast adrift.

So, how’s it going? A lachrymose and yet fraternal lift to the question.

Hamilton is the possessor of an inchoate originality. The sequence of his thoughts is quite simple and therefore peculiar. Some years back he had found in himself a sort of vegetative conservatism, something he came upon in his diggings, like the struggling stump of a briar rose in a neglected garden. He fell in love with the capitalist “theorem,” as he called it, because of the philosophical beauty of the way foods and goods came into New York City each morning. Oranges from Florida, hamburger from the Middle West, avocados from California, dresses from Milan, lumber from Canada, crackers from Sweden and soup mix from Switzerland.

This distributive astonishment augments to the miracle of immense corporations circling the globe, overseeing like a schoolmistress a random class of automobiles, wheat, hides, medicines, tractors. Computers and jams, shoes and fountain pens combining in one company name on the stock exchange struck him as a phenomenon of Euclidean beauty. To that he added a deep scholarly interest in the tragic fall of overreaching individuals in the drama of commerce and finance. Kruger, Richard Whitney, Bernard Cornfield lived out their destiny in an Aeschylean mode.

So, how’s it going? Ackermann quickens his pace and now he and Hamilton are treading the cement together. Hurrying along, Hamilton offered in a tone of secret information the details of all the attacks Ackermann and his kind had received in magazines and newspapers in the last months. D.’s review was puzzling, was it not? And then he commended the reciprocating attacks, some subtly hidden and some forthright.

The lances and steeds of the battlefield, the flags, the ambush from the hills, the counterattack on the sleeping troops under a pale moon rise up in his discourse and carry Hamilton high above the unremarkable buildings, the noise of the buses and the terror of the crossings. The crowds, the shops with their anxious clerks behind locked doors, machines grinding carrots, oranges, and papayas vibrated in the sunlight. The world was spinning on its axis and some spectacular mercantile power was reigning with the serene command of Michelangelo’s great curled and bearded Almighty.

Ackermann at last kindly touches the tweed shoulder, faces his ally with a now-cramped smile, and hails a cab. Out of the back window as he moves away, he can see Hamilton standing alone in the heart of the metropolis. A lonely offspring of old New York, or old Boston, or old Connecticut: the Eastern establishment with all the gloss ground down to a white powder which now is blown about mercilessly by a sudden vicious wind from the Hudson.

The blue sky remains, the friendly winter atmosphere prevails, and Miriam and Hamilton leave the stage as the taxi makes its way across Central Park by means of the growls of a surly black driver. Ackermann has the day and evening free and more than that he is to be alone for ten days and the idea is that he will write and write when he is not occupied with the many calls on his attention.

What times these are. His wife is a sociologist and a commentator on the affairs of women, the family, day care, sex, and much more. At this moment she is in Sweden attending a conference. It is her intention to offer her audience a number of arresting thoughts. She plans to say: the most discriminated-against person in the United States is the talented white male. This statement with its clear rhythms and daunting novelty is flying across the North Atlantic with the stunning velocity of the century’s inventive spirit.

Madison Avenue—a feline thorough-fare with goods and mirrors meant to intimidate bone and flesh. A scourging idealism, a snarling transcendence watched over by clerks as insolent as the pet eunuchs of a sultan. The feminization of taste lightly troubles Ackermann, even if it is as old as history itself. Monarchical wigs, ruffs, lace handkerchiefs in a fop’s sleeve, and now very young girls in fedoras and frontier belt buckles. Crossdressing, androgyny: a mine of significations in the streets and on the bodies. The new AT&T cathedral—an aesthetic of the recession? Or the spacious, arched mouth of the recovery? As a conservative, Ackermann is no less an aesthetician than he was as a more or less Marxist young man.

Yesterday composing his memoir he had risen like a kite above the exposition, risen to explore an interstice of his experience of the national life.

“Spoiled, beguiling girls, all was to be yours by divine right. Starved, rich American girls with shoulder blades like the points of sabers….”

Ackermann has in mind here a small, brown-skinned girl, Joanna, an heiress, a minor heiress descending in a wayward line from early natural gas pioneers. He is aware of a green patch of feeling for Joanna and for their brief love affair ten years ago. Ring the downstairs bell, wait, climb the stairs of the brownstone, enter the small, neat apartment, see the freesia in a white vase, hear the ice crackling in the glass, listen to Harold in Italy, watch the bare feet in the lamplight near the bed…

On the avenue the restaurants are snoozing in the afternoon lull, in the florist shops what appear to be frozen tulips from Holland hold up their heads, polished antiques sit in sedate arrangements, decorated porcelains unfaded and unchipped by the dust cloths and soapsuds of a century patiently await their destiny. The sky begins to cloud over in a sudden metamorphosis of intention. The word, snow, appears in the drift of voices.

In front of a fashionable bookshop, glossy jackets and black type, new novels and stories. Too many, Ackermann believes, about laid-back young adults, husbands in pickup trucks, drinking beer and driving across the country in flight from not one but two wives and various children; too many inward, hypochondriacal reveries. In the last year he has written a long essay on these fictions and the toil of it, the vehemence of his adjectives make the glowing reds and blues and the patent-leather gloss of those he has censured almost an affront.

Wasn’t it Kant who understood that when we say “in my opinion,” we mean instead, “all men able to judge will agree”?

Joanna lingers in his thoughts—the sweet, little nut-brown face and the memory of their picturesque secret life, of excursions at twilight. If he were to meet her, she would say: What is your story? Where have you been? Dear Joanna has a mind fixed like a footprint in cement. The ACLU, the Sierra Club, Committee for an Effective Congress, Planned Parenthood. She is shy as a nun but there was her face in a recent copy of The Village Voice. Joanna in the shrieking bowels of Penn Station, trying to persuade a homeless woman to go off to a shelter. An outrageous beauty Joanna is, a skinny phantom in the steaming glare of the station.

At the end of the afternoon Ackermann is at home once more. Solitude, quiet. He plays back his telephone messages for the day. Snow is falling softly outside the window where he stands with a drink, dreaming. Theatricality is not out of place for one who has in the last decade experienced an unexpected U-turn in his thoughts. Where have I been? Sometimes he thinks of himself as having set out in an oxcart across the plains or he is one who set sail in a leaky boat in search of the mouth of the Mississippi.

Joanna, shall I tell you about old D., ragged as a Zouave after a skirmish, and his compendium of New Deal and Fair Deal bacteria swimming in the naive blood of America? Something like that, only drier, more suitable to intimate discourse, but still colorful and affecting. Or his own private vision on the road?

In Miami in 1972, at the time of the Republican Convention he stood at the dinner hour outside the Fontainebleau Hotel and watched the delegates and their families, modest Republicans, unworldly and very boring, he thought. Strangers. They were wearing outfits of red, white, and blue, dresses and hats and shoes bought in the department stores of middle-sized cities. While he was standing there a girl rushed up to the front of the hotel and took off her clothes. She stood there turning like a model, giving her message. The people stared in confusion, in silence. They were seeing it at last—the Sixties. Ackermann decided at that moment to vote for Nixon. He published his intention and thus his new life, far from the instructing old thinker and the abashed red, white, and blue citizens, began.

The hospitable evening skyline, a tempest of incandescent meteors. Ackermann cannot see the culminating stars of the sky-city to the south of him, but surely a white light shines in the Empire State tower and the squares of private life on high floors are a glamorous zodiac of bulls, crabs, lions, goats, and virgins. Below him men and women suddenly appear in country boots and jackets and release their steamy breath like horses in pasture. Dogs on leashes leap to the snow and in the window across from him a large cat questions its fate.

It is time to remember things left unfinished, the heartfelt boyish duplicity of sudden loves, romances lightly erased so that their traces remain on the calendar of promiscuous memory.

Once, exaggerating, expanding, and also censuring, he told his wife, Donna, of his brief love for Joanna. Donna, small, quick, and decisive, with a bee-like cleverness generally quite consoling, gave him a friendly, diminishing glance and said, That’s OK. But that’s enough.

That’s enough? So, in love he was a mere spot; out of love he could be what he liked, a writer, a thinker, an imposing person, parent of two hard-working goddess daughters, one in medical school, one in law school. He could be Donna herself—and that is marriage.

But here is the snowy night, die Winterreise, the solitude and sleepy nostalgia, the down of memories, the years shuffling away, the dust of youth. Everywhere people in bars and restaurants are behaving, under the eye of the waiter, with an insinuating politeness quite agreeable and interesting. Many are laying out their biography in patterns: first this and then that and all that is neither this nor that.

At eleven o’clock Ackermann in suede boots and fleece-lined coat, looking like a farmer out to inspect the barn, gets into a taxi and tells the driver to go to Penn Station. With Joanna he will rescue a homeless lady. Yes, he will be coming in from Princeton, a traveler pacing homeward in the station. And she will say finally, Where have you been and what’s happened to you?

The station is awful, an unsuitable rendezvous. Most of the kiosks are masked by metal bands as gray as sleet, the record shops have stilled their hoarse invitations. Only a few taverns and one big magazine stand are awake in the unswept gloom.

He sees a woman propped up against the wall. She is faithful to type, being a human bundle surrounded by unfathomable lumps of treasure. Her face is covered by a scarf and she sleeps like an ethnographic item shipped in the hold from Calcutta. He listens to the horse hooves of the subway; his eye sweeps up and down the cavern and he does not discover the angel of hope, Joanna.

Outside, a midnight Thirty-fourth Street. A marauding emptiness; shaved heads of dummies in Macy’s windows. The end of the day. It is over and the snow falling on these streets is gray and dull, as if it had picked up ash on its passage across the city. All he meets as he waits for a cab is a transvestite in a muskrat coat, hobbling home on sequined heels.

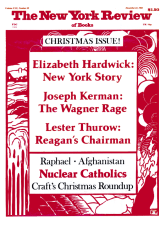

This Issue

December 22, 1983