Whereas George Orwell was down and out in Paris, Bohumil Hrabal’s narrator and hero, Ditie by name, is upwardly mobile in the hotel and restaurant world of Prague. Ditie loves his labors. In some respects his experiences resemble those of Thomas Mann’s Hochstapler Felix Krull, who did nicely for himself while working at the Hotel Saint James and Albany in Paris.

Though his story is picaresque in its episodic nature and its wanderings, Ditie is not a swindler or a picaro on the grand scale; he is merely ambitious, ambitious to be rich, and prepared to work devotedly in furtherance of this aim. His book is a fairy tale: a poor boy, mocked for his short stature, goes out into the world, succeeds here and suffers reverses there, has many adventures on the way, and at last achieves true happiness. It isn’t necessary to be big, you just have to feel big. Unlike most fairy tales, this one is suffused with irony, and not—in parts obviously not—suitable for children.

Ditie’s first job, as busboy at the Golden Prague Hotel, is to sell hot frankfurters at the railway station. He soon perceives that when frankfurters cost one crown eighty apiece, and the passenger gives you a twenty-crown bill or even a hundred, if you fumble about in your pockets looking for change, the odds are that the train will have moved off before you can hand the change over. It’s not your fault if you make a nice little profit. This pays for Ditie’s visits to an amiable establishment called Paradise’s, where the girls teach him skills that will come in handy later on. He also discovers that “money could buy you not just a beautiful girl, money could buy you poetry too.”

Moving to the Hotel Tichota, Ditie picks up more useful knowledge from the proprietor, a hugely fat man confined to a wheelchair, who nonetheless whizzes around the premises and is aware of what everyone is up to. Observation, in particular of merry orgies, confirms that, contrary to folklore, it is the rich who are happy, not the poor and honest. When rich people retire to the washroom to vomit during a banquet, it is a sign of good breeding. Suspected of conspiring to steal a gold statue of the Bambino di Praga, Ditie is sacked, but “I was always lucky in my bad luck.”

His next job is at the beautiful Hotel Paris, where he is taken up by the headwaiter, Mr. Skrivánek, a person who knows everything, who can virtually read minds, simply because once (he explains) he served the King of England. Old gentlemen hold voyeuristic sessions in the hotel, sipping champagne and studying connoisseur-like the folds and curves of a young female body; and it is left to Ditie to finish the job after they have left. Once a week, for those few minutes, he would feel “tall and handsome and curly-haired.”

But the great event at the Hotel Paris is a state banquet given for the Emperor of Ethiopia and his entourage, held there because only the hotel has sufficient gold cutlery for three hundred guests. The Emperor’s cooks prepare a native specialty: hard-boiled eggs and stuffing and fish are placed inside twenty half-roasted turkeys, the turkeys inside two antelopes (acquired from the zoo), the antelopes inside a barbecued camel, and then the whole is basted with mint leaves dipped in beer. The dish is so carved that in every portion there is a slice of camel and antelope and turkey and fish and stuffing and hard-boiled egg. Noticing that the Emperor has no wine, Ditie kneels to him and fills his glass, for which he is rewarded with a medal and a blue sash “for service rendered to the throne of the Emperor of Ethiopia.”

Ditie’s happiness is shattered when he is suspected of having stolen one of the gold spoons. He rushes off into the woods to hang himself, stumbles in the dark against the pendent body of someone who has already hanged himself, faints, and is rescued by the all-knowing headwaiter. The missing spoon has been found halfway down the drain of the kitchen sink. Unmistakably a fairy-tale denouement. But when he falls unpatriotically in love with a Sudeten German girl, Lise, he is fired in earnest.

This stands him in good stead when the German army arrives, and his next job is serving milk to young females and wine to young males at an establishment run by the Bureau for Racial Purity, a “breeding station” for a refined and noble human race, by means of “no-nonsense intercourse, as the old Teutons used to do it.” Ditie’s reputation there is as high as was Mr. Skrivánek’s in the Hotel Paris, perhaps higher, since to have served the Emperor of Ethiopia would probably outrank having served the King of England. Ditie is regrettably undersized, but he can claim a conceivably Teutonic grandfather, and at least has blond hair. Hence the Good Waiter Ditie is permitted to marry Lise, who is now an officer in the nursing corps and a high-ranking member of the party. “With a mighty thumping of rubber stamps I was given a marriage license, while Czech patriots, with the same thumping of the same rubber stamps, were sentenced to death.” The testing of his semen is related with what may be considered an appropriate lack of taste. Appropriate also, no doubt, is the fact that from the couple’s regulated and unenjoyable acts of “National Socialist intercourse” the only issue is a cretinous child christened Siegfried.

Advertisement

It is another instance of being lucky in his bad luck that Ditie should be arrested in error by the SS, beaten up, and thrown into prison just as the war is coming to an end. His battered face declares him an anti-Nazi fighter, although as an undeniable sexual collaborator he gets a six-months’ jail sentence.

Lise is killed in an air raid, but Ditie recovers the suitcase she has packed with valuable stamps, once Jewish property. With the proceeds he buys an abandoned quarry outside Prague, and builds himself a unique “landscaped” hotel there, visited by such celebrities as John Steinbeck (who tries unsuccessfully to buy it) and Maurice Chevalier. As he intended, he has become a millionaire. In 1948 the new regime confiscates the hotel, all property rights having devolved to the people, and there follows a hilarious episode in an easygoing internment camp (earlier a Catholic seminary) for former millionaires, who are supposed to serve one year for every million they have made, and who look down on Ditie as not a proper, prewar millionaire but a wartime profiteer. Hearing that the camp is to be shut down, the inmates arrange a last supper. The circle begins to close: Ditie puts on his tuxedo, and the medal and the blue sash, and waits on them, but there is no joy in it, and guests and guards alike end by gazing at a painting of the Last Supper and then kneeling in the chapel.

Facing a choice between going to prison and joining a labor brigade, Ditie takes up his last job, mending a remote road in the mountains that nobody uses. He settles in an abandoned inn, together with his friends or “guests,” a cat, a goat, and a horse, and meditates on death and eternity. The brook in which he washes his face tells him that years from now “somebody somewhere will wash his face in me,” just as someone somewhere will strike a match made from the phosphorus of his body. Whatever traces of irony still linger quickly fade away, and out of the book for good. First the fun and games, and then self-arraignment, repentance (not too strenuous), and spiritual rebirth.

To maintain the country road is to maintain his own weed-infested life, to open up his past, the past life which now “seemed to have happened to someone else.” Given strength by the Emperor’s medal, he sits down in the evenings to write out his story, this largely and surprisingly humorous European Bildungsroman or, as he puts it, “this story of how the unbelievable came true.”

Ivan Klíma’s My First Loves relates to much the same time-span as I Served the King of England, and the second of its four linked stories features a wise old violinist, formerly a waiter and a major-domo who once served the Austrian Emperor with a glass of wine at a banquet in Vienna. He tells the young narrator that people shouldn’t look down on those who are not ashamed to serve others, for which of them doesn’t serve? “I’ve always maintained that a man can do anything so long as he does it lovingly.” The remark is a gentle corrective to the boy’s egalitarian notions, but sentiments very similar could have come from Ditie.

The narrator—we have some authority for calling him Ivan—is given to speculating on the meaning of life, on God, and the soul, and immortality, but otherwise the stories are very different: sad, introspective, inconclusive, and above all steeped in uncertainty. In the first story, set during the German occupation, the keynote is sounded when the youthful narrator, who hopes for a future as a witness-bearer, a painter or a poet, asks the ghetto painter Maestro Speero, originally from Holland, why his drawings—of lines of tiny people wearing the Jewish star—are so very small. “Um sie besser zu verschlucken,” the painter seems to say: all the better to swallow them; or it could have been “verschicken,” to send, or “verschenken,” to give.

Advertisement

In the second story, “My Country,” set in the early postwar years, and portraying a “strange intermingling of different periods” in the behavior of the residents in a country inn, Ivan’s father, an engineer, voices the idealistic Communist vision of a future in which poverty and exploitation will be no more, heavy labor will be done by marvelous machines, the people will govern, and, since there is no reason for war, an age of universal peace and trust will dawn. A doctor contends that the only result of revolution will be that a different group of people become poor and a different group rich, and the promised paradise will turn out to be a fairy tale. The boy falls in puppy love with the doctor’s inviting wife, but only in the great writers he is reading at the time—Balzac, Stendhal, Maupassant—are love affairs actually consummated. Showing people and events through the eyes of youth, inquiring, half-understanding, sometimes mystified, this is the most engaging of the stories.

The war had dragged on through Ivan’s childhood “like some poisonous snake.” And no sooner has the adolescent narrator entered the promised land foreseen by his father than his father is arrested and charged with unbelievable crimes against the new social order in which he believes. “The Truth Game,” as its title suggests, is a sourer tale, although Ivan does at last get to make love. Vlasta, the girl in the case, claims a family history which even for that time and place seems extravagant in its woes: her father was executed by the Nazis for possessing an illegal transmitter; the new regime sent her stepfather to jail for some obscure reason; her mother drowned herself; Vlasta herself married a drunken saxophone player who used to beat her up. The family has had one hero, but he was on the wrong side: an uncle who emigrated to America, joined the navy, and was blown up by a mine in Korea. “I visualized my father lying in a cell somewhere while I was drifting about wine bars with a strange dolled-up divorcée,” a woman whose copious revelations didn’t add up, who was “covered in words like fish-scales.”

The long-awaited satisfactions of sexual liberation are promptly marred by Vlasta’s confession that she was sent to work on a farm in the Sudetenland toward the end of the war and she had a baby there, which she smothered. What was one little corpse among so many?

In addition, she now lives in terror of someone called Karel, a murderer, ex-SS, who wants her to draw a plan of the factory where she works. Ivan takes her to the police station; what happens there is left untold; she disappears; her landlady doesn’t recognize her name and has no address for her. A few years later Ivan sees her in a wine bar with an elderly man. She greets him cheerfully and gives him her new address, which proves to be false, like the various names she has used. Was she an agent provocateur, a spy, a prostitute, a victim, or simply a compulsive liar? A British critic has attributed the vacillations, deceit, and faithlessness of the women in these tales, and the fact that the tales are uncompleted, to the corrupting poison of communism. Such may have been the author’s intention, or part of it, but the explanation seems a little glib: Ivan brings much of his wretchedness on himself, and his sex-starved hopes and conscientious misgivings are not peculiar to any particular social or political system.

The final story shows the narrator at his least endearing. For one reason or another—wartime experiences or the self-pity typical of his age—he has “never quite been able to surrender to pleasure or joy, or to relax.” Faced with reciprocated love, he loses his nerve; to be taken seriously is harder to handle than being rejected or deceived or toyed with. Admittedly, the girl is weird (her parents were both executed during the war), and extremely sick, recovering from meningitis, perhaps not recovering. For her part, she proposes a life spent together in love. Ivan doesn’t want to lose Dana; he is sure he would “manage” to be fond of her, “but I just wasn’t ready for anything of the sort.” When he mentions how receptive a listener she is—“I watched my words dropping into her like some instantly sprouting seeds”—it looks as though roles have been reversed since the preceding experience, and it is he now who is covered in words like fish-scales. But then, he is already a writer, with “grand goings-on” inside his mind, as is proved by a touching (and germane) story of his, about a bedridden girl released from her sufferings by a luminous angel, which he gives to Dana.

Toward the close, Ivan watches some tightrope walkers, whose exploits prompt the thought that life is “one continual performance above the abyss,” and a man must go forward without looking behind or down. “I must begin my own performance, my grand unrepeatable performance.” The next day, as he waits for Dana to arrive at their meeting place, the tightrope walkers have departed, and so has his resolution. The reader is left hanging.

Besides other things, My First Loves (which has not been published in Czechoslovakia) is a portrait of the artist as a would-be dog. We feel sympathy for Ivan, who has grown up in a time difficult for a writer (though potentially fruitful, too), but we also feel irritated by his doggedly solipsistic distresses. We must await the promised translation of Klíma’s first full-length novel, Judge on Trial, concerning a good man and just magistrate in an evil and unjust world.

The hero of Catapult, Jacek Jost, “33/5’9″, oval face, brown eyes and hair, no special markings,” is an engineer in a textile company, and obliged to travel frequently across Czechoslovakia, between the factory in Ustí and Labem in the north, where he lives, and the head office in Brno in the south. En route he acquires seven girlfriends, most of them through an ad (representing himself as divorced) placed in the personal column of a newspaper. All seven assume he will marry them; all seven come up with new careers for him. In the space of seven printed pages Jacek manages to meet all seven of the women (one of them is reading Páral’s own novel, The Trade Fair of Wishes Come True, aha!) and return to the bosom of his lawful family.

It is the old story of a girl in every port and, despite the book’s subtitle, “A Timetable of Rail, Sea, and Air Ways to Paradise,” a story that is bound to end badly. Jacek also advertises for a mate for his unsuspecting wife, described as a divorcée, though only one of the applicants is at all promising, a cheerful dwarf called Tomas Roll, who follows him around in order to understudy the role and provides the book’s most entertaining moments. Eventually Jacek grasps that freedom is “just the maximum degree of deprivation,” since however many paths he opens up, he can follow only one of them. He might as well stay with his wife and young daughter. At the end he appears to have lost everything, including possibly his life.

It can be argued that, like Hrabal in parts of I Served the King of England, Vladimír Páral has come out of Hašek’s overcoat, but unhappily in this novel of 1967 he donned a garment of a different cut, the once modern mode of stream of consciousness and free association, stylistically underlined by the use of commas rather than full stops to separate sentences, and abrupt transitions from one location or time to another. In comparison The Good Soldier Svejk is a model of classical form. Catapult’s chief propriety lies in the omission of any blow-by-blow account of Jacek’s sexual activities, the presence of which would have made the book twice as long. In his introduction the translator, William Harkins, claims that the hero’s roots go back to such mythic figures as Don Juan, insatiable lover, and Doctor Faust, insatiable for knowledge and experience, although he “lacks the spiritual stamina of his two prototypes,” and it is this failure, “a comic failure born of inadequacy, that makes him a true child of our century.” Stamina is what the reader will need, irrespective of whether or not he or she is a true child of our century.

According to the end note Páral’s novels of the 1960s, including the present one, were “sufficiently apolitical to be published,” whereas Harkins calls this novel “a parodic exposé of Eastern European socialism.” Perhaps Harkins is nearer the mark in declaring that Jacek could exist equally in a Communist or a capitalist society: his comic flights of fancy “are inspired both by the gulf between his dreams and the dreariness of reality and by the gulf between his would-be abilities and the triviality of his real achievement.” That is true, but doesn’t mean very much since we just don’t feel any affection for Jacek. (Joyce’s Leopold Bloom, another dreamer, does engage affection and respect.) As for the “mythic figures,” they are a myth, I fear. The most one could contrive in that line would be to think of the story as a parody of Stakhanovism.

The novel has a rackety energy, stalwartly passed on by the translator, affecting the reader rather like a bumpy ride on an overfast train. Perhaps the book’s most endearing feature is the helpful list of characters and pronunciation, and the publisher’s suggestion that the page containing it should be cut out (directions given) and used as a bookmark. “If this book is yours, don’t hesitate to mutilate it, no matter what your teachers said. If it’s a library’s, please leave the bookmark where it is so that others can use it.” That’s telling us. The contrast with Jacek’s unremitting irresponsibility is stark.

Monsignor Ronald Knox, a friend of G.K. Chesterton and himself a writer of detective stories, once drew up a new decalogue for practitioners of the genre stating, for example, that no more than one secret room or passage was permissible, no hitherto unknown poisons might be used, no Chinaman should figure in the story (a note explains that this prohibition wasn’t inspired by racist feelings), and the detective himself must not commit the crime. Josef Skvorecky has been enjoying himself by breaking the ten commandments one by one in ten stories set in various countries. The first and last feature his old Prague policeman, Lieutenant Boruvka, a man of “mournful demeanor,” but the chief mover is a disenchanted Czech nightclub singer bearing the name Eve Adam, a slender blonde with beautiful eyes and gorgeous legs, quite a chick albeit not exactly a chicken. While the language approximates to the American hard-boiled (Hammett, Chandler), the stories are much closer to the English “Golden Age” of detective fiction (Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, locked rooms and stopped watches) in asserting the primacy of reason and deduction. Violence occurs offstage; brain takes precedence over brawn.

In his novels Skvorecky inclines to write diffusely, allowing his characters’ tongues too free a rein, though it must be granted that the subject matter of The Engineer of Human Souls called for length and was perfectly suited to Skvorecky’s inventiveness, love of detail, and capacity for making connections and sustaining a theme. His stories, and notably the novella The Bass Saxophone, have proved that he can write economically when he wants to. Sins for Father Knox consists of “entertainments,” the term Graham Greene used for such lighter works of his as The Third Man and Our Man in Havana: relaxed, breezy, devoid of tragic tinges or deep psychology. Eve has knocked about the world, and been knocked about in the process, and that, along with feminine intuition (a sin against the Holy Knox), is enough psychology for her.

There are casual jokes, including the running one that so irritates Eve: faced with her figure, her eyes and legs, practically every man she meets fancies himself in the role of Adam. The name of a suspect in a California kidnapping is William Q. Snake, and one of the bars Eve sings in is called The Paradise. (Rather less earthy than the establishment known as Paradise’s, which the young Ditie used to patronize. The thought occurs that latterly the word “Paradise” in East European writing nearly always has something to do with sex.) A “dear departed shamus” is reported to have given his life “to keep an easy lady from being an easy lay,” and we hear in passing “some old poem about a peer and a ploughman.” There is more than a touch of culture around. Eve was educated at a bishop’s lyceum and wanted to study theology, but war and revolution prevented all that—which is why she now works for Pragokoncert, singing in the nightclubs of the world, and bringing foreign currency into “our beloved socialist state” while also bringing shame down on it by the way she perforce (though also by inclination) comports herself in those capitalistic dives. Private enterprise gains her a mink coat, and she persuades an American tourist to carry it through customs for her.

In each tale the reader is challenged to spot both the guilty party and the commandment broken. Some of the mysteries are tricky in the extreme. I succeeded with the first two or three, but then succumbed to the distractions of post-lapsarian Eve, who bats her false eyelashes so seductively that they almost come unglued. In Skvorecky’s hands detective fiction, “this decadent form of literature” as he calls it tongue in cheek, becomes even more decadent. He is always good with women characters, even if his women are not in themselves unequivocally good. Eve would have made a stimulating addition to Ditie’s menage of cat and goat and horse. What a great first lover she would have been for Klíma’s sad young hero! Conversant with aspiring Don Juans and failed Fausts, how swiftly and conclusively she would have sent Páral’s Jacek packing!

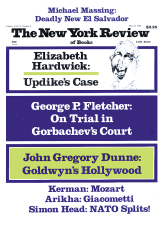

This Issue

May 18, 1989