For the greater part of human history mountaintops were imagined rather than visited. As well as being desolate and difficult to reach they had in many cases been appropriated by gods and goddesses, either as permanent homes or as settings for special effects designed to overawe the humbler creation. Moses ascended the smoking and quaking mountain in the wilderness of Sinai unscathed, but only because he was there by special invitation. The rest of the children of Israel very prudently stood afar off. Petrarch, the indefatigable fourteenth-century interpreter of the Greek and Roman classics, is said to have been one of the first men in modern times to climb a mountain. The ancient authors he was studying would probably have shunned such an enterprise for fear of offending some resident deity. Even in the middle of the nineteenth century, when the pioneers of modern mountaineering first set out to climb the Matterhorn, local people assured them that it was the home of demons who would lure them to their deaths.

And so when Swift at the end of the seventeenth century began his satire The Battle of the Books with an account of a quarrel at the summit of Mount Parnassus he had no means of knowing what the top of the mountain was really like. He had to invent his own high-altitude topography, sustained by what Joseph Levine rightly calls “a curious kind of imaginative power so far unequaled in English literature.” Swift’s Parnassus had two peaks, one higher than the other and each inhabited by some rather seedy demigods. Those on the upper summit were patrons of the ancient authors of Greece and Rome while those on the lower favored more modern writers such as Milton, Dryden, Descartes, and Hobbes.

All these deities were surprisingly domesticated and had so far forfeited the usual privileges of divinity as to have to do their own digging. The moderns on the lower peak threatened to “come with their shovels and matlocks” and hack away at the upper one until it was brought down to their level. The ancients suggested instead that the lower peak should be raised and offered to help with the necessary spadework. Their offer was spurned and battle was joined not only on the mountaintop but also in the king’s library, where the librarian was so shockingly prejudiced in favor of books written by the moderns that the works of the ancients had to leave their shelves and fight it out. The great writers and thinkers of ancient times, Homer, Plato, Aristotle, Virgil, were pitted against such eminent seventeenth-century authors as Bacon, Hobbes, Milton, and Dryden.

In one respect at least Swift’s imagination had not deceived him. Parnassus had two peaks. Although the mountain in its heyday was sacred to Apollo it had earlier been the preserve of Dionysus, a very different and far less disciplined god. Even at Delphi, Apollo’s shrine cradled in the foothills of Parnassus, there were memories of older and bloodier rites. The Greeks who came to Delphi to consult the oracle of Apollo, supposedly the god of clarity and logic and reason, were familiar also with the dark ecstasies of Dionysus. And so they hedged their bets. They decided that Parnassus had two summits, one sacred to Apollo and the other to Dionysus. It was not a geographical observation but an insight into the human condition. The Greeks knew full well what Freud was to point out many centuries later: Apollo’s victory over Dionysus, the conscious mind’s control over the unconscious, would never be complete. It could have been said of the twin peaks, as Voltaire was to say of God, that if they had not existed it would have been necessary to create them.

The nine Muses, who inspired history and literature along with other arts and sciences, were followers of Apollo. The writing of books was his province, part of that dissemination of enlightenment and reason on which he was said to be engaged. But the battling of books, the fusion of Apollo’s supposed intellectual calm with the uncontrolled frenzies of Dionysus, brought both gods into disrepute. Thirty years earlier, in Paradise Regained, Milton had made Satan’s temptation of Christ in the wilderness culminate in an offer of the wisdom and cultural splendor of ancient Greece. Christ had replied contemptuously that Greek literature was nothing more than a series of debased and unintelligent borrowings from the Hebrew writings of the Old Testament. For good measure he had added that the Greeks were shameless and their gods ridiculous.1 Now it would seem that Swift was ready to endorse this verdict, at any rate as far as the gods were concerned.

Yet he was supposed to be the champion of the ancients. His aim was to mock the moderns, those critics who claimed that contemporary literature had outstripped that of Greece and Rome. And attacks by the moderns on the old gods were already proving effective. In particular they ridiculed the way these supposed immortals behaved in the pages of Homer, using men and women as vehicles for their petty squabbles. The two antagonists of Mount Parnassus had lost face for other reasons, Dionysus because most of the things for which he had once been held responsible could now be put down to the promptings of the Devil, and Apollo because recent advances in astronomy and other sciences had made his efforts to enlighten mankind seem redundant. Newton is said to have believed that his discoveries about the nature of the universe had been foreshadowed in the seven strings of Apollo’s Iyre;2 but in this he was exceptional, perhaps even a little eccentric. So why should Swift transform the twin peaks of Parnassus from an allegory of eternal truth into a couple of rival encampments where undignified demigods brandished shovels at one another? This readiness to play the opponents’ game might be thought puzzling, but it does not seem to puzzle or even interest Levine. Perhaps he too thinks that by this time there was no longer any reason to take the gods of Greece seriously.

Advertisement

It is certainly true that on the Grecian front, from Mount Olympus to the twin peaks of Parnassus, the war was not going well for the supporters of the ancients. But, as Levine’s subtitle suggests, things looked brighter farther to the West, in and around the seven hills of Rome. This was the dawning of a new Augustan Age: writers and thinkers from Dryden to Pope in England, from Descartes to Racine in France, were seen as regenerating and reproducing the glories of the reign of the Roman emperor Augustus at the beginning of the Christian era. And the gods of Rome, though for the most part modeled on those of Greece, had commanded a different sort of respect. Deference to the gods and deference to earthly rulers formed part of the same disciplined pattern. The gods were dependable divine policemen rather than capricious mythological archetypes. In order to strengthen still further this bond between secular dominion and established religion the emperors of Rome were made into gods as soon as they were dead. Secular sway on earth merged smoothly and almost indistinguishably into a divinely ordained authority which would last forever. It would be a brave man who would instruct Jesus Christ to dismiss the Romans as shameless and their gods as ridiculous.

As well as having more acceptable gods the Romans also had more acceptable poets. The elder Pitt once declared in the House of Commons that he could learn more from a couple of passages in Virgil or Horace than from all the political literature of his own day.3 Horace was admired for his protestations of sturdy independence—even though he had in fact been totally dependent on the patronage of Augustus and his friend Maecenas—and Virgil enjoyed a posthumous special relationship with the Christian world, having acted as guide to Petrarch’s contemporary Dante when he toured Hell and Purgatory and Heaven. The Aeneid, Virgil’s epic about the fall of Troy and the founding of Rome, was never subjected to attacks as vicious or as damaging as those leveled against Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey.

But if this was a new Augustan Age, who was the new Augustus? It would not be easy to persuade the English, king-killers and fervent parliamentarians, to admire or emulate ancient Rome’s descent from sturdy republicanism into imperial tyranny. Swift started to write The Battle of the Books in the closing years of King William III’s reign and by the time he published it Queen Anne was on the throne. Both monarchs had had their powers much curtailed and neither came anywhere near being deified, even though Goldsmith was later to look back on the reign of Queen Anne as England’s true Augustan Age. And of course Rome to most Englishmen meant the hated and feared Roman Catholic Church. “The Papacy is not other than the Ghost of the deceased Roman Empire, sitting crowned on the grave thereof,” Hobbes had declared in the middle of the seventeenth century.

And so it was not surprising that the new Augustus was on the other side of the English Channel. Louis XIV of France, resplendent in his palace of Versailles, was the Sun King, the new Phoebus Apollo, able to put both gods and emperors into the shade. As the divinely appointed ruler of the most populous and most powerful nation in Western Europe he demanded and received the homage of men of letters throughout his kingdom. It was French rather than English that seemed poised to replace Latin as the international language of educated men and women; and it was in the Academy, the French king’s agency for the patronage and control of writers, that the quarrel of the ancients and the moderns turned from an academic squabble into a political issue. In January 1687 Charles Perrault read before the Academy “The Age of Louis the Great,” a poem in which he suggested that the literary glories of the Sun King’s reign would outshine those of all earlier epochs, including the great ages of Greece and Rome. He followed this up with his Parallel between the Ancients and the Moderns which appeared in several volumes between 1688 and 1697. He met with fierce opposition, particularly from Boileau, a distinguished critic and historian. The two men eventually reached what was supposed to be a reconciliation but was in reality an uneasy truce.

Advertisement

Levine describes this stage of the dispute as a confrontation of nations, “a quarrel between the France of Perrault and the England of [Sir William] Temple.” Perrault may possibly be said to have represented France, since he was on what seemed to be the winning side and was in favor at Versailles; but whether Temple represented England is more doubtful. He was a prematurely retired public servant, a man whom Macaulay later accused of having “avoided the great offices of state with a caution almost pusillanimous.” When “this childish controversy spread to England”—again the words are Macaulay’s4—Temple took up the cause of the ancients in his Essay upon Ancient and Modern Learning and was foolish enough to hail as a masterpiece a Greek text which was later shown to be spurious. The counterblast from the moderns was devastating and it was as well for Temple that he had taken Swift into his employ and into his confidence. Swift fastened on the fact that Richard Bentley, the most formidable of Temple’s opponents, was keeper of the king’s libraries. The result was The Battle of the Books. By the time it came out Temple was dead, and very soon he was forgotten by all but the controversialists themselves. The England of the early eighteenth century was certainly not the England of Temple.

Nor was it the England of Bentley or of Swift. Both men lived on for another forty years, Bentley as Master of Trinity College in Cambridge and Swift as Dean of St. Patrick’s in Dublin. Bentley won respect as a scholar and critic but became increasingly unpopular at Trinity, where he was a harsh and domineering Master. Toward the end of Anne’s reign Swift threw in his lot with the Tories and so found himself cut off from further advancement when the accession of George of Hanover in 1714 gave the Whigs an almost total monopoly of power and influence. Swift soon came to regard his appointment to St. Patrick’s as a vindictive sentence of banishment and he raged with darkening fury not just against his literary and political opponents but against the whole of mankind.

Perrault was of an earlier generation, more than thirty years older than either Swift or Bentley. He died in 1703, full of years and confident that the supremacy of the moderns, the triumph of contemporary French culture over that of earlier ages, was now assured. A dozen years later the Sun King himself died. Soon the literary and cultural ramparts which he and his ministers had built around the throne began to show some ominous cracks. The control and censorship of literature remained government policy but its implementation proved increasingly difficult. French thinkers and writers still led the world but what they thought and wrote became steadily more subversive. The proclamation and celebration of the Age of Louis the Great had paved the way not for the apotheosis of absolute monarchy but for its overthrow.

But if France was the France of Perrault it was not because he championed the literary heritage of his own time but because he brought to light an older and richer heritage. In 1697, just as he was bringing his Parallel between the Ancients and the Moderns to a conclusion, he published Mother Goose’s Tales, a collection of stories about Puss in Boots, Cinderella, the Sleeping Beauty, Red Riding Hood, and other traditional heroes and heroines and villains. As well as winning far more readers than all his other works put together these tales had a profound and lasting effect on European culture.

It was an odd irony that this man who was so offended by the coarseness of the Greek epics, by the brutality of their heroes and the capricious behavior of their gods, should have uncovered immemorial fables in his own country which told of a world as violent and as subject to supernatural intervention as anything in Homer. Perhaps the real parallel that needed to be drawn was not between ancient and modern writers but between the myths of ancient Greece and those of modern Europe. Madame Dacier, one of Perrault’s opponents, complained, Levine tells us, of “the Gilding that defaces our Age, its Luxury and Effeminacy, which most certainly beget a general corruption in our Souls”; and she insisted, as did many others, that the Homeric epics served to recall to an enfeebled and decadent generation the heroic values of earlier times. Exactly the same could have been said of Mother Goose’s tales; but they of course were intended only for children and so they could hardly be cited in the argumentation of scholars.

Gradually but inexorably this view of things began to change. It was to take more than a century for the term “folklore” to be accepted into the language of scholarship; but already the myths and legends of all nations and of all ages were pushing their way up from the lowliness of the nursery to the respectability of the library shelves. Soon it would be the controversy that would seem childish—at any rate in the eyes of Macaulay and those readers who paid him respect—while the fairy stories basked in the approval of anthropologists and students of comparative religion. In Germany Herder laid the foundations of such studies almost single-handed, while at the same time insisting on the supremacy of the gods of Olympus and Parnassus. He it was who told Goethe in 1770 that if he wanted to reach out for eternal truth he must first learn Greek. In 1788 Schiller published The Gods of Greece, proclaiming that if the old gods were indeed dead then something was dead in the soul of man. What hope was there for a generation that had thrown the Sun God from his chariot and turned it into a ball of burning gas?

It is often said that Schiller was heralding what the propagators of generalization have dubbed “Romanticism,” the swing of history’s pendulum away from the “Age of Reason.” Was this another manifestation of the dual nature of Parnassus, a flight from Apollo’s clear and luminous peak to the dark mysteries of Dionysus? Hardly, since it was Apollo who had been ousted by the Age of Reason’s ball of burning gas. Romanticism seemed more like a joint triumph of both gods, of both peaks. Wordsworth was not alone in thinking that he might like to be “a pagan suckled in a creed outworn.” And the old songs and stories of the fabled past came back along with the old gods. While Keats paid his homage to “deep-brow’d Homer,” Wordsworth imagined the solitary reaper singing of “old, unhappy, far-off-things / And battles long ago.” It was an echo of Madame Dacier’s stern prescription of Homer as a cure for luxury and decadence. Romanticism could be seen as a great adventure, a mighty leap from the lulling security of modern times to the excitement and challenge of a more primitive world.

It could also be seen as senseless nostalgia. It does not seem to have occurred to the Romantics that some ancients might have been as keen to become modern as some moderns were to become ancient. The Greeks might have made good use of the principles of Newtonian physics and some of them might even have been glad of a steam engine to haul them up the steep paths at Delphi. Hence the distinction which Levine makes in his introduction and to which he frequently returns, the distinction between imitation and accumulation. Literature was largely a matter of imitation, of deciding which examples to follow, and so here the supporters of the ancients were reasonably successful; but it was far harder to maintain that in the sciences, where each generation had to build on the accumulated knowledge of its predecessors, all that had been achieved since the days of the Greeks and the Romans should be rejected. It was as well that Romanticism extended only to literature and the arts. Scientific investigators suckled in a creed outworn might have made comparatively little progress.

Levine scorns such speculations. “I shall retell a story that was once famous,” he tells us at the beginning of his book, “although it is now largely forgotten or misunderstood.” His retelling is meticulous: every twist and turn of the controversy is set out in detail and all the participants are minutely docketed. He does his best to ensure that nothing is forgotten and that nothing can any longer be misunderstood. And after he has taken us from the 1690s to the 1730s he assures us that the story is now at an end: “In short, the arguments of both the ancients and the moderns were finally transformed in such a way that the old quarrel disappeared.” He has already warned us at the outset that he has “chosen to begin deliberately in medias res,” without any attempt to set the scene or examine the origins of the dispute: and now at the end there is an equally brusque refusal to put things into context. “It might be possible to trace the echoes of this conflict throughout the century,” we are told loftily, “but it would not be easy and it would not advance our story very far.”

That rather depends on what you think the story is about. Some forty years ago, in the course of a masterly account of Greek and Roman influences on Western literature, Gilbert Highet remarked that the quarrel between the ancients and the moderns opened up a gap between scholars and the general public.5 He thought this somewhat sad but Levine seems to regard it with equanimity. He does indeed give us at one point a quotation from a certain Thomas Smith, who told the Earl of Clarendon in 1699 that the controversy had entered into “ordinary conversation and entertainment”; but for the most part we are required to forget the general public and stay with the scholars. In Levine’s book Perrault appears only as a controversialist and there is no mention either of his political importance or of his wider literary fame. Hermes is the only Greek god included in the index and he is there as Hermes Trismegistus, the name under which he was transformed by medieval mystics into a cabalistic Egyptian priest. Yet classical influences permeated eighteenth-century life at many levels, not all of them the province of wrangling academics. In the end the true gods of Olympus and Parnassus may turn out to have been as important as the battling books.

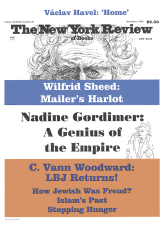

This Issue

December 5, 1991

-

1

Paradise Regained, Book IV, lines 338–342.

↩ -

2

J. E. McGuire and P. Rattansi, “Newton and the Pipes of Pan,” Notes and Records of the Royal Society, Vol. 21 (1966) pp. 108–141; cited in Frances A. Yates The Rosicrucian Enlightenment (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1972), p. 248.

↩ -

3

H. Walpole, Memoirs of the Reign of George the Third, four volumes (London: Lawrence and Bullen, 1894), Vol. i, p. 75. However, Horace was not as widely respected as has sometimes been thought: see Howard D. Veinbrot, “History, Horace and Augustus Caesar: some implications for eighteenth century satire,” Eighteenth Century Studies Vol. vii, No. 4 (Summer 1974), pp. 391–414.

↩ -

4

T. B. Macaulay, Critical and Historical Essays (London: Logmans, Green, 1883), pp. 416, 459.

↩ -

5

G. Highet, The Classical Tradition: Greek and Roman Influences on Western Literature (Oxford University Press, 1949), p. 288.

↩