In response to:

Shakespeare & Co. from the April 9, 1992 issue

To the Editors:

I appreciate very much indeed your having printed in the issue of April 9th my letter responding to Professor E.A.J. Honigmann’s article on “The Second-Best Bed.”

In taking issue with a review or article, one should generally expect to come out the worse, since the author being challenged is given the right to reply and thus has the last word, generally only compounding his offense, if such there was. In this case I am very glad to have had my letter printed since I feel the points that Prof. Honigmann offered in rebuttal are not very strong. He concludes by propounding “Two short questions for Mr. Ogburn:….”

The first question is: “Is there any evidence that ‘outsiders erected the monument?’ ” The answer is, yes, evidence that would appear to settle the issue. On page 215 of The Mysterious William Shakespeare: The Myth and the Reality, which Professor Honigmann presumably read before reviewing it for your magazine (and paying it a very nice compliment, by the way), I observe: “His [Shakspere’s] widow and daughters were certainly not responsible for the memorial. They would not have approved an inscription that put the body in the monument when they had buried it years before under the floor. Moreover, to the immediate family a member’s first name is of particular importance, since the last name is common to all. And no ‘William’ appears on the monument.

The second question asks if the author of Susannah’s epitaph did not attribute distinction to her father with the claim that she was “Witty above her sex” and “wise to salvation,” and that “Something of Shakespeare was in that.” My answer is that if Professor Honigmann can believe that the greatest writer in our language and perhaps in any other could, as far as we know, achieve no greater recognition of his genius on the part of his fellow townsmen and of their children and grandchildren than that he was witty and wise to salvation, then I can only reply that Prof. Honigmann’s imagination is far more elastic than mine. Incidentally, as I point out in The Mysterious William Shakespeare, wit is, to the best of our knowledge, the only commendable trait ever recognized in Will Shakspere by his contemporaries. Even as late as 1773, a minister traveling in Warwickshire reported that “All the idea that the country people have of that great genius is that he excelled in smart repartee and the selling of bargains, as they call it.”

As for the size and importance of Stratford-upon-Avon, of which my critic makes much, I may quote again from my book (page 273): “And what kind of town was that? ‘An important center of trade, the business metropolis of a large and fertile area.’ Metropolis? So Oscar James Campbell of Columbia University says. In fact, in 1590, the town comprised 217 houses. Calculating from recorded births and deaths, [Charles] Knight estimates its population in the year of Shakespere’s birth at 1,400. It does not even exist for the Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd (also of Columbia) assigned me at Harvard, which recognizes only the Stratford near London.”

Believe me, there is inexhaustible fascination in this field for those who can surmount the barrier of the professoriat.

Charlton Ogburn

Beaufort, South Carolina

E.A.J Honigmann replies:

Mr. Ogburn claims that “outsiders…erected the monument to ‘Shakespeare’ in Trinity Church, clearly as part of the scheme to deflect to the Stratfordian the interest certain to arise in the identity of the mysterious poet-dramatist ‘William Shakespeare.’ ” He believes that the Earl of Oxford wrote the plays and poems usually attributed to Shakespeare, and that, anxious to conceal his identity, Oxford used the name of the actor from Stratford. This reattribution involves Mr. Ogburn in a gigantic conspiracy theory, one that soon collapses under its own weight. Oxford died in 1604, therefore Mr. Ogburn thinks that all Shakespeare’s plays were written, or partly written, by that year. After his death, Oxford’s secret was protected by the Lord Chamberlain, whose brother was Oxford’s son-in-law. The Cecils, the Herberts, Ben Jonson, and many more participated in the cover-up, so efficiently that no one suspected it until the twentieth century! And of course the First Folio of 1623 and the Stratford monument were also part of the cover-up….

I find it difficult to follow Mr. Ogburn’s reasoning and prefer the traditional view of the monument, as expressed by Samuel Schoenbaum: “The monument in Holy Trinity was presumably commissioned and paid for by one or more of the surviving adult members of Shakespeare’s immediate family” (William Shakespeare: A Documentary Life, Oxford University Press, 1975, p. 254). Schoenbaum is also a more up-to-date authority on Shakespeare’s Stratford than Charles Knight, who died in 1873.

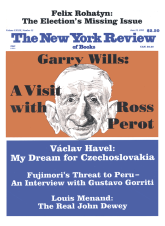

This Issue

June 25, 1992