Histories of the staging of Shakespeare’s plays have changed a good deal in the decades since G.C.D. Odell’s extensive Shakespeare from Betterton to Irving, published in two volumes in 1920. The fascinating new books by John Gross and Marvin Rosenberg are both brimming with fresh ideas and information that will ensure their being read for decades to come.

As his subtitle shows, Mr. Gross’s book is much more than a stage history of Shylock. He begins with “an account of the elements that went into” Shylock’s making—stereotypes of Jews as they were seen before Shakespeare—and then traces Shylock’s fortunes “in the theater, at the hands of critics and commentators, as an inspiration to other writers, as a symbol and a source of debate.” He is concerned not only with Shylock but also with “the history of folklore and mass-psychology, of politics and popular culture”—and particularly with the history of anti-Semitism.

Before Shakespeare created Shylock, the myth of “the Jew” portrayed a poisoner (like Marlowe’s Barabas in The Jew of Malta), a sorcerer, a ritual murderer—in short, a monster. Shakespeare reactivated the myth but according to Mr. Gross “muted some of its uglier aspects.” On the other hand, “there is no hint in Shylock of an inner faith, or of religion as a way of life…[His] stage-Judaism is a pseudo-religion, a fabrication.”

Naturally Mr. Gross wonders how much firsthand knowledge of Jews went into the invention of Shylock.

Officially there had been no Jews in the country for centuries. But a handful of Marranos, crypto-Jews from Spain and Portugal, made their way to London during the reign of Henry VIII, and a somewhat larger colony, numbering perhaps a hundred in all, established itself during the reign of Elizabeth.

Outwardly these Marranos were Christians, “but they retained many Jewish affiliations, and some of them may well have practiced Jewish ceremonies in private.” Could Shakespeare have known any? “Yes—but there is absolutely nothing to show that he did.” There is no hard evidence that Shakespeare ever met a Jew. But what of the amazing “Jewishness” of Shylock, so different from any Jew in pre-Shakespearian literature? (“Jewishness,” says Mr. Gross, “is one of his primary characteristics; he emphasizes it himself, and it is emphasized for him by everyone with whom he has dealings.”) Did Shakespeare create this Jewishness ex nihilo and impose it on a mindlessly unresisting world, or did Shylock become an icon because many take him to be quintessentially Jewish, even if less agreeably so than any Jew they have personally known? “To the audiences of the world Shylock is the embodiment of the Jew,” says Supposnik, a character in Philip Roth’s Operation Shylock, “in the way that Uncle Sam embodies for them the spirit of the United States.” In a recent review of Roth’s novel Harold Bloom called Shylock “the ultimate Jew,” and added:

Is there a more memorable Jewish character in all of Western literature than Shylock? As a critic, not a novelist, I myself am unhappy at confessing that I do not know a stronger Jewish character than Shakespeare’s anti-Semitic creation, who has an existence as convincing as Hamlet or Iago even though compared to Hamlet or Iago he speaks only very few lines.1

Shylock is a libel, but at the same time so convincing that he—together with Tubal and Jessica, in effect a Jewish community—must have been based on direct observation.

But how? Some years ago I read the following, in an early version of the modern newspaper. “Saturday, 2 June [1655]. This day some Jews were seen to meet in Hackney; it being their Sabbath day, at their devotion. All very clean and neat, in the corner of a garden, by an house, all of them with their faces towards the East; their Minister foremost, and the rest all behind him.”2

An unusual event, it seems. The not unfriendly tone is interesting—and such a “meeting” might just have been witnessed by Shakespeare in the 1590s, when he wrote The Merchant of Venice. The play, however, raises the possibility of something more than the playwright’s glancing contact. So we must remember that many foreigners came to London, and that Shakespeare seems to have sought them out. For instance, he actually lived as a lodger with a French Huguenot family, from about 1602; the Globe theater was built by Peter Street, a carpenter and contractor of Dutch origin; our only surviving likenesses of Shakespeare, the Stratford bust and the First Folio engraving, were the work of Gheerart Janssen and Martin Droeshout, both members of London’s immigrant community.

Even more to the point, Shakespeare wrote Othello not long after a Moorish embassy arrived in London. The Moors caused quite a stir,3 and Shakespeare, as a servant of the Lord Chamberlain, could easily have observed them. I believe that there is every likelihood that Shylock—like Othello, Fluellen, Dr. Caius, and many more—was distilled from raw materials personally encountered, or even sought out, by the dramatist.

Advertisement

Either at home, or perhaps abroad, Shakespeare seems to have come across a Jewish family, or community. (And why not abroad? Was he less curious about human diversity than Marlowe, Jonson, Donne, and all the other writers who managed to cross the seas?) Yet Mr. Gross makes out a good case for believing that however far Shakespeare traveled, he did not get as far as Venice, at any rate by the time he wrote The Merchant.

More than 2,500 Jews had settled in Venice by 1600, in the Ghetto Nuovo and the Ghetto Vecchio. “The ghetto system, which was subsequently adopted, along with the name ‘ghetto,’ by other Italian cities,” is not referred to by Shakespeare.

Shakespeare’s knowledge of Jewish life in Venice was clearly very limited. It is true that in a number of respects the picture he draws coincides with actual conditions. He is right, for example, in his assumption that Shylock’s legal status is that of an alien…. But there are also mistakes, such as the notion that a Jew would have been allowed to have a Christian servant living in his house, in the way that Lancelot Gobbo does.

And “Shylock would no more have felt free to dine with Bassanio, as he does in the play, than Bassanio would have felt free to invite him.” (A question: Although Shylock changes his mind later, does his first reaction, when invited to dinner, not mean that Shakespeare knew how strongly Jews felt about kosher cooking? “Yes, to smell pork, to eat of the habitation which your prophet the Nazarite conjured the devil into! I will buy with you, sell with you, talk with you, walk with you, and so following; but I will not eat with you…” [Act I, scene iii]).

Tracking Shylock and his interpreters through the centuries, and through many countries, Mr. Gross expresses doubts about various familiar reductions of the play to oppositions such as Judaism vs. Christianity or Justice vs. Mercy. “Needless to say,” he explains, “the notion that Judaism has an inadequate grasp of the concept of mercy is a travesty—as much of a travesty as it would be to suppose that Christianity has an inadequate grasp of the concept of justice…endless exhortations to deal mercifully can be found in the writings of the Rabbis.”

He is equally opposed to simplifications of Shylock. “Shylock would not have held the stage for four hundred years if he were a mere stereotype.” Yet Macklin’s Shylock of 1741 (described as “unyieldingly malignant”) seems to have come close to a stereotype, and is treated generously by Mr. Gross: this was “one of the great triumphs of the eighteenth-century stage.” He leaves us in no doubt, though, that later performers had a better understanding of Shylock’s complexities. Particularly Edmund Kean (from 1814) and Henry Irving (from 1879), both strong on “dignity,” two of the greatest Shylocks of modern times.

Kean’s “impassioned acting” worked for and against Shylock, making him more three-dimensional than Macklin’s. Audiences thrilled “to the sudden musical charm of [Kean’s] voice when he addressed Jessica, to his chuckle when he said ‘I cannot find it in the bond.’ ”

At the exclamation, “I would my daughter were dead at my foot, and the jewels in her ear! would she were hearsed at my foot, and the ducats in her coffin!” [Kean] started back, as with a revulsion of paternal feeling…[and he] gasped an agonizing “No, no, no.”

As for Irving, Shylock’s complexities first dawned on him while on a Mediterranean yachting cruise. He landed at Tunis, and there saw a Jewish merchant, “at one moment calm and self-possessed, then in a helpless rage over a dispute about money…. He was never undignified until he tore at his hair and flung himself down…he was old, but erect, even stately…. As he walked beside his team of mules he carried himself with the lofty air of a king”—a performance transferred direct from Tunis to the Lyceum Theatre, London (except that, inexplicably, Irving omitted the team of mules).

While he dislikes stereotypes, Mr. Gross is admirably open-minded about many different interpretations of Shylock, accepting that the spirit of the play “can cover a number of possibilities.” I thought him too open-minded about Shylock’s opponents.

Ease, grace, attractiveness—those are the province of [Shylock’s] enemies….We should not take the professions of the “gentle” characters entirely at face value. They can be decidedly businesslike when it comes to pursuing their own interests….But that does not mean that we are supposed to “see through” them, or to identify them with their limitations.

This is generosity to a fault, and Mr. Gross knows it. He worries about Bassanio and his friends, and the audience’s response to them, and later returns to this issue as if fingering a wound.

Advertisement

He is aware, of course, that many critics have expressed a different view. Hazlitt could “hardly help sympathizing with the proud spirit [of Shylock],” and was unhappy about the “triumphant pretensions of his enemies”4—Hazlitt, though, was a “man of the left,” and therefore, it seems, predisposed to quarrel with the establishment. Thomas Campbell, who thought that Shakespeare traces the blame for the play’s racial antagonism “to the iniquity of the Christian world,” was likewise on the political left, and (hmm!) “was also closely associated with the Jewish financier and philanthropist Isaac Lyon Goldsmid.” Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch may have dismissed most of the play’s Christians as either “wasters” or “rotters,” but we don’t need to take him too seriously since he was “nearly fifty when he first became a don in 1912, [and he] retained much of the free and easy style of the man of letters” (a sad put-down, from the author of The Rise and Fall of the Man of Letters).

I am being unfair: Mr. Gross’s scattered asides, as he disposes of “dissident” interpretations, must not be ascribed to prejudice but rather to his anxiety to do justice to both sides. That said, should we not look beyond the prejudices of later critics (most of them seem to have been prejudiced one way or the other), to the prejudices of Shakespeare’s own day? In Shylock’s case, and also in Bassanio’s?

Critics who claim that we are not asked to “see through” the “attractive” young Venetians pay too little attention to a crucial speech in the first scene, Bassanio’s request for a loan.

‘Tis not unknown to you, Antonio,

How much I have disabled mine estate

By something showing a more swelling port

Than my faint means would grant continuance.

Nor do I now make moan to be abridged

From such a noble rate; but my chief care

Is to come fairly off from the great debts

Wherein my time, something too prodigal,

Hath left me gaged…

(Act I, scene i)

What would be immediately obvious to an Elizabethan playgoer, and less so to his modern descendants, is this: Bassanio, a young gentleman from the upper reaches of society, must have inherited his “estate,” and squandered it; he now owes “great debts,” a second fortune, also squandered; and he goes on to ask for a very large loan, a third fortune that he proposes to shoot away in “pure innocence” (as he puts it), a final throw of the dice.

You don’t have to be Shylock to see that this is an irresponsible style of life. Classical satirists and their Elizabethan imitators had little patience with it (“They were careless people,” said Scott Fitzgerald of the rich young “Christians” of Long Island Sound), and this is the prejudice triggered off by Bassanio’s first big speech. Indeed, even earlier, by his very first words, which are often so character-revealing in Shakespeare: “Good signiors both, when shall we laugh? Say when?”

Even if the “Christian characters have admirable ideals, and on the whole…live up to them,” Shakespeare does not allow us to forget that Bassanio’s attitude to money is as wrong-headed as Shylock’s. Lancelot wants to serve Bassanio because he hands out “rare new liveries”—who pays? “We’ll play with them the first boy for a thousand ducats”—whose ducats? Having cleverly repudiated gold and chosen the leaden casket, Bassanio talks of Portia’s face as “a golden mesh t’entrap the hearts of men”: one is tempted to echo Yeats, who exclaimed so felicitously on being telephoned with the news that he had won the Nobel Prize—How much? Such questions rarely break the surface of the play, yet the unease of a host of critics (even if they have fine Jewish names like Hazlitt, Campbell, and Quiller-Couch) suggests that we are meant to be conscious of them, just below the surface.

Mr. Gross rejects the notion that the Christians are supposed to be “taken ironically,” and he is right. Shakespeare’s view of Bassanio is less severe than Napoleon’s of Talleyrand (“a mass of filth in silk stockings”); nevertheless, it is not entirely uncritical. He wants us to “see through” Bassanio, just as we see through Shylock.

It was not Shakespeare’s way to be entirely uncritical. On the other hand, it was one of his favorite tricks to contrast an attractive surface and the hidden reality, and in The Merchant this is a central preoccupation. Shylock talks politely with his enemies, until suddenly the volcano erupts—“Hath not a Jew eyes?” To those who are dazzled by the “ease, grace, attractiveness” of Shylock’s enemies, the play retorts: “All that glisters is not gold.”

Shakespeare’s exploration of “false glitter” (Milton’s phrase, speaking of Satan) comes to a head in the play’s final scene, which is so often mis-managed in the theater. “The revels can now proceed,” says Mr. Gross, and in most productions they do, almost as if the real business of the play had already ended. Yet, below the surface, the last scene makes a serious point, by reenacting the trial scene: after the entrapment of Shylock, the entrapment of Bassanio. Portia’s control of the scene is as formidable as in the discomfiture of Shylock, her strength contrasting with Bassanio’s weakness. For, although the men appear to be in charge as their thoughts turn toward bed and sexual activity, masculine bluster and bawdy (“I’ll mar the young clerk’s pen,” Nerissa’s ring) cannot conceal the fact that Portia, the feminine principle, has her own ideas. Another contrast, another hidden, threatening reality.

Looking at “Shylock and the Jewish question” one can scarcely avoid being curious about the ethnic background of the actors and critics involved, their ethnic parti pris, and here again Mr. Gross is helpful. F.S. Boas wrote with “strength of feeling” of The Merchant, which must “surely be related to the fact that Boas was Jewish himself.” Ernest Milton, an outstanding and “inflammably racial” Shylock, was “part-Jewish.” Maurice Moscovitch was Jewish—“unmistakably so” (whatever that means). Beerbohm Tree was suspected of being Jewish (“There is no evidence that he was”); George Arliss was suspected—and why? Because he played Shylock (“steely, sardonic, well spoken”) and also starred in the films Disraeli and The House of Rothschild. Junius Brutus Booth was convinced that he was of Jewish descent, but this was wishful thinking. Solomon Lazarus renamed himself (Sir) Sidney Lee, another kind of wishful thinking.

Whenever Shylock is performed or discussed one senses wheels within wheels, allusions and connections blurred by the mists of time. Mr. Gross mentions that Kean, as Shylock, abandoned the traditional “Judas wig,” which was red, switching to a black wig and beard; he almost ignores Kean’s more extraordinary innovation, reported by Hazlitt.

When we first went to see Mr. Kean in Shylock, we expected to see, what we had been used to see, a decrepit old man, bent with age and ugly with mental deformity….

Why these changes? Kean’s more youthful Shylock, in particular, was not only a surprise at the time but has had few imitators—is he not called “old Shylock” in the play? The answer may be that Kean wanted to remind spectators of one of London’s leading Jewish figures—perhaps Nathan Rothschild, the most brilliant member of a gifted family, who became a British subject in 1806, acted as a money-lender and broker on a huge scale, and would have been thirty-six when Kean opened as Shylock. Nathan’s brother James was later satirized as “M. de Shylock of Paris.”

Irving’s Shylock prompts a similar question. Did he mean to remind audiences of Disraeli? When Disraeli stood for Parliament in 1835 he was lampooned as the “cruel, revengeful, bloodthirsty Jew in The Merchant of Venice.” Disraeli’s head, as represented by Millais, resembles that of Irving’s Shylock in the well-known portrait: projecting lower lip, goatee beard, a straggle of hair across the forehead, a mass of hair at the back of the head.5 Irving’s Merchant opened in 1879, Disraeli resigned as prime minister in 1880, and, unavoidably, Disraeli’s Jewishness was emphasized in caricatures (Punch depicted him as an ingratiating Jewish shopkeeper). Years later W. Graham Robertson, a theatergoer for more than fifty years, recalled that when he saw Irving’s Shylock as a boy he noticed “just a touch of Lord Beaconsfield [i.e., Disraeli] that made for mystery.”

There have been other books on Shylock—Herman Sinsheimer’s Shylock: The History of a Character (1947) and Toby Lelyveld’s Shylock on the Stage (1960). I have concentrated on “the legend and its legacy,” the subject of Mr. Gross’s book, yet that is not to say that he is not equally perceptive in his comments on the words of the play. To take one of Shylock’s most quoted speeches, when he hears that Jessica has exchanged a ring for a monkey: “Out upon her! thou torturest me, Tubal—it was my turquoise! I had it of Leah when I was a bachelor: I would not have given it for a wilderness of monkeys!” This, says Mr. Gross, “is one of those Shakespearean sentences that go a mile deep… It is as though Jessica were trying to undo her parents’ entire marriage at a stroke.” One might add that Shakespeare also gives us, in passing, a tantalizing glimpse of a younger Shylock. If only Queen Elizabeth had noticed and, instead of asking for a comedy called Sir John in love (i.e., The Merry Wives of Windsor), had asked for one called Shylock in love!

The Masks of Hamlet follows three earlier volumes (The Masks of Othello, 1961; The Masks of King Lear, 1972; The Masks of Macbeth, 1978), all now reissued by the University of Delaware Press. Mr. Rosenberg adopts the same procedure as before, a line-by-line and often word-by-word analysis of what actors have done and of the comments of editors and critics: a procedure greeted with strictly qualified rapture by some of his reviewers. Like many others, I found Mr. Rosenberg’s volumes illuminating—so what was the fuss about?

It has been said that the Masks volumes are not stage histories at all, insofar as readers are not given a clear idea of the overall strategy and continuity of individual productions, only brief extracts from actors’ memoirs, reviews, and the like, confusingly thrown together. And that Mr. Rosenberg, casting his net across continents and centuries, in the end catches mere fragments, and nothing of substance.

I have to admit that on first looking into Rosenberg’s Hamlet, almost a thousand pages, the longest of his four books, I felt that here was a mountain that I would rather not climb. Theater productions, films, interviews, private communications, videos, from Finland, Holland, Hungary, Japan, Norway, Poland, Sweden, etc. etc., and actors such as Karatygin, Mochalov, Adamian, Kachalov—why should I want to read about them?

I am glad that I persisted, for of course Mr. Rosenberg did not set out to write a conventional “stage history” (any more than did Mr. Gross), and the Hamlet volume is at least as rewarding as its three predecessors. What, then, can be said on the positive side? Here is a representative extract (on the first line of Hamlet’s first soliloquy, “O, that this too too solid flesh would melt…”):

The O, Hamlet’s first private sound,…has often compressed in a single utterance his whole anguish. Kemble lingered on it, Tieck remembered, with a long, quivering cry. Kainz, his head arched backward in stress, his hands pressing against his chest, sobbed a painful, long-drawn-out moan…. Irving…breathed the first line “as one long yearning.”

To be sure, by the time he reaches this point (p. 209), a reader may have forgotten who Kainz was or when he acted—so many dozens of unfamiliar names are thrown at us that the effect can be bewildering. But the problem solves itself: we soon realize that we are not required to remember names and dates—we are simply invited to evaluate every interpretative decision on its merits, irrespective of the actor’s or critic’s reputation. Mr. Rosenberg lays the options before us, not without a warning that further options remain: and I know of no other writer who has done more to explain the extraordinary range of possibilities in Shakespeare’s scenes, speeches, lines, and single words. Occasionally he may seem to go too far, as if determined to leave nothing out. When one considers, though, how many productions and books he assembles, and that some are just cited once or twice, one sees that a strenuous sifting process has vastly reduced the material.

One of the special merits of Mr. Rosenberg’s work is that he manages to bring actors and critics together. The critics are prominent whenever he introduces a new character (this is done at each one’s first entry in the play: 94 pages on Hamlet, 23 on Claudius, 12 on Gertrude), though the theater is never forgotten. Thus: Gertrude comes to life “mainly in the language of gesture.” She speaks only 157 lines, fewer than Ophelia. “She must be, as one Gertrude said, ‘a good listener.’ She must manifest the theatre axiom that what the actor can show when not talking reveals the actor’s quality.”

Mr. Rosenberg divides performers of Hamlet into the “sweet” and the “powerful” (adding, characteristically: “you may want to consider this generalization with caution”). Kean was the “power” Hamlet par excellence: he “exploded onto the [London] stage in 1814” (the year of his Shylock), though without sacrificing Hamlet’s intellectuality and sensitiveness. Irving went the other way, almost too far so, even for Victorian tastes; he was described as “womanish”—which meant, apparently, that “he would have clasped the whole world to his bosom.”

Apart from the help he gives with major critical problems, Mr. Rosenberg is good on production problems. He knows what triumphs one may look forward to if privileged to play the Ghost in Hamlet, a part supposedly chosen by Shakespeare himself: in 1787 the Ghost, in full armor, “fell clumsily, and could only roll to the footlights, where his plume caught fire and he had to be doused in a tub.” The cock-crow (“a dangerous theatre sound…the wrong volume, the wrong intensity, can provoke laughter”) should be subdued, inconspicuous. And how Mozartian should we aim to be with our “ghost music”? For the film Hamlet Olivier “superimposed recordings of fifty women shrieking, fifty men groaning, and twelve violinists scraping their bows across the strings on a single screeching note.” He wanted a sound “like the lid of hell being opened.”

But perhaps Mr. Rosenberg’s greatest achievement is that The Masks of Hamlet can claim to be so truly international. Some of the actors in remote countries may be unable to read the play in the original, yet they struggle with production problems that engaged Burbage and Olivier: if they have a good idea, we want to know about it. After all, somewhere in the world Hamlet is performed virtually every hour of every night and day, and simultaneously read by thousands. The play belongs to the whole world, and Mr. Rosenberg tells us what the world has made of it. I hope that he has started on the next thirty-two volumes.

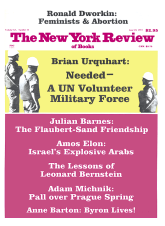

This Issue

June 10, 1993

-

1

The New York Review, April 22, 1993, p. 48.

↩ -

2

Perfect Proceedings of State-Affairs, in England, Scotland and Ireland, No. 297 (spelling modernized).

↩ -

3

See Bernard Harris, “A Portrait of a Moor,” Shakespeare Survey 11 (1958), pp. 89–97.

↩ -

4

Hazlitt, Characters of Shakespeare’s Plays.

↩ -

5

Compare Sir John Everett Millais, Benjamin Disraeli, 1881 (in the National Portrait Gallery, London: NPG 3241) and Irving’s Shylock in Toby Lelyveld’s Shylock on the Stage (Western Reserve University Press, 1960), p. 78. G.C.D. Odell reproduced a contemporary photograph of Irving as Shylock (Shakespeare from Betterton to Irving, Scribner’s, 1920; frontispiece of Vol. 2).

↩