If you snowshoe up Blue Mountain, which is more or less in the middle of the Adirondacks, you look out over the greatest wilderness in the East. I’ve lived in this wilderness most of my adult life, and yet every time I get up high I am startled by its rugged emptiness. You see lake and forest and ridge and then lake again, stretching out in every direction. The Adirondacks, a mixture of public and private land, cover six million acres, about a quarter of New York State. That makes it bigger than Yellowstone, Yosemite, Glacier, and Grand Canyon National Parks combined, not to mention bigger than the state of Massachusetts, bigger than Connecticut, about the same size as Vermont but with one sixth the population. Along with the city five hours to the south, this park is one of the Empire State’s two great gifts to the planet. In many ways it’s the place where the world’s sense of wilderness was born.

It’s also, right now, politically the most exciting spot in the state. In three days at the end of 1997, Governor George Pataki—who controls this wilderness because it is a state, not a federal, park—ended years of dithering by Albany and began taking aggressive steps to chart the park’s future course. He committed $11 million to closing the last small local landfills in the park, effectively ending large-scale schemes to import vast amounts of urban trash into the Adirondacks. He canceled plans to build a super-maximum security penitentiary at Tupper Lake, which would have been the seventh prison in what was becoming an Adirondack gulag. And, by far the most important, he announced that the state would buy 15,000 acres of crucially important land in the center of the park.

This land, the heart of the baronial Whitney Estate, which included the largest privately owned lake east of the Mississippi, was about to be divided up and sold. Instead it will now be at the core of the park’s largest wilderness area, one big enough to allow the possible reintroduction of species like the wolf. If the land had slipped from the grasp of the state—as happened with another key parcel during the Cuomo administration—the park would forever have had a gaping hole in the middle. Now, the Whitney deal opens the prospect that the state will finally ensure both the ecological integrity of the park and its economic future as a working forest. The fate of about 350,000 additional acres of land now in private hands will soon be decided. Most of it is owned by large timber companies which would like to sell “conservation easements” and “recreation rights” to the state, while continuing to harvest trees—an outcome that would help to protect the jobs of Adirondackers as well as the intact mantle of green that makes the park stand out on any map of eastern North America.

Still it’s not yet certain that Pataki will finish what he has started. He continues to employ a right-wing opponent of conservation to head the crucial Adirondack Park Agency. Gregory Campbell, whom Pataki appointed, is a New York version of James Watt. In the past Campbell has been in favor of allowing motorized vehicles into the park’s wilderness (and even in private nature preserves run by groups like the Nature Conservancy). He is currently under investigation by the New York State inspector general for allegedly altering the official agency minutes in order to conceal his support for renewed clearcutting of park forests, and even if he survives that inquiry, his actions will continue to undermine Pataki’s achievements in the Adirondacks.

But the events of late 1997 were heartening to all who care about the park’s environmental and economic future. The strange and delicate arrangements that have allowed the Adirondacks to reach the twenty-first century in spectacularly good shape remain more or less intact. As both books under review make clear, that is the unlikely miracle of Adirondack history.

Paul Schneider’s The Adirondacks is a popular history, a collection of tales and local lore. Most of its early chapters take place only on the fringes of the Adirondacks—either on Lake George and Lake Champlain, which formed the border with New England and were the main north-south route (and battleground) between the British and the French holdings in the New World, or along the Mohawk River, south of the park, which was the center of the Iroquois Confederacy. The central Adirondacks themselves were used mostly as a hunting ground by either the Iroquois or the Algonquin who settled in the river valleys to the north. They were too high, too cold, and too densely forested for convenient settlement (conditions that persist to this day); indeed, one derivation of the word “Adirondacks” is “barkeater,” a Mohawk taunt flung at those Indians who tried to live in the mountains and were forced to gnaw on trees.

Advertisement

The purely Adirondack part of Schneider’s account really begins with the story of William Johnson, the fur trader and Indian agent who established one of the park’s first empires in the early eighteenth century. His lavish wooden summer houses along the Sacandaga River were the first recreational homes in the region, and to them he brought his retinue of slaves, his dwarf violinist, and his Mohawk bodyguards. But his vast schemes for further development, like those of many others, eventually collapsed; it wasn’t until the nineteenth century that people began to leave a strong mark on these mountains. Not until 1837, in fact, did Europeans (or perhaps anyone) climb Mount Marcy, at 5,344 feet New York State’s highest peak.

That is, decades after Lewis and Clark had returned from the Pacific, the Adirondack region remained an unsurveyed, unknown, and mostly wild place. “It makes a man feel what it is to have all creation placed beneath his feet,” said John Cheney, the local guide who led that first ascent. “There are woods there which it would take a lifetime to hunt over, mountains that seem shouldering each other to boost the one whereon you stand up and away, heaven knows where. Thousands of little lakes among them so light and clean.”

Schneider describes the many nineteenth-century artists who descended on the Adirondacks in search of the “Sublime” (Thomas Cole, Arthur Tait, and Winslow Homer were regular visitors; one well-known painter counted forty of his colleagues painting under white sun umbrellas in the fields around Keene Valley and the Ausable River). And Schneider recalls the armies of loggers who came to clear the last great eastern forest, and the armies of city swells who came here to escape temporarily from the Industrial Revolution, supporting the great hotels (one on Blue Mountain Lake was the first hotel in the world wired for electricity, and by Thomas Alva Edison himself) and, if they had the resources, building “great camps,” rustically constructed mansions that they filled with astonishing displays of taxidermy.

Others came too—consumptives who believed the mountain air would restore them, miners seeking what was for a time some of the highest-grade iron ore in the world, Boston and New York preachers looking for a brawny God in this wild place. Schneider is good-humored in telling us their stories, but, as he makes clear, his work draws heavily on the original research of more professional historians, chief among them Barbara McMartin, the excellent chronicler of the park’s natural history,1 and Philip Terrie, a social historian at Bowling Green University in Ohio.

Terrie’s own recent account of the Adirondacks, Contested Terrain, is more scholarly than Schneider’s, though every bit as readable. It is also the finest general Adirondack history yet written, the book to which all subsequent accounts will have to refer. Instead of recounting the colorful tales of the Adirondacks, Terrie examines the ways different groups with different interests thought of the Adirondacks, and how those conceptions clashed.

For instance, he describes the surveyors and state officials who explored the region before the Civil War, and saw it as, essentially, the same kind of frontier that was being opened far to the west. Ebenezer Emmons, who headed the first party up Mount Marcy, believed that where the seemingly impenetrable forest now stood, there would soon be “the golden grain waving with the gentle breeze, the sleek cattle browsing on the rich pastures, and the farmer with well-stored granaries enjoying the domestic hearth.” (He was prescient, at least in a global sense, in believing that clearing the forest would warm the climate.)

That essentially Ohioan story about the Adirondacks soon gave way to others. After the Civil War, as the swarm of well-to-do outsiders moved northward to invade the place, they invented an altogether different myth: the Adirondacks were a refuge of wild mountains and wild people, especially the local guides who figured prominently in every account of what was the world’s first large-scale example of ecotourism or adventure travel. The visiting adventurers had no time for small towns and agricultural communities. They saw Adirondackers as people from another world. In the words of one well-to-do tourist, who observed his guide talking to an Indian near Tupper Lake, the two men were

representatives of a class unknown to cultured life; the old, bronzed hunter and trapper; and the wild red man, united by their habits and modes of life, and both so perfectly in keeping with the scenes where I saw them—the natural meadow—the primeval woods—the lonely lake—the log hut—the wolf dogs—all so different from the objects to which I had become accustomed.

Visiting the Adirondacks was the nineteenth-century equivalent of taking a cruise to an “exotic” port filled with “happy” natives who would pose for you, talk with you, even take you into the wilderness.

Advertisement

That story came into conflict with a growing force of the same era—the large-scale commercial logging that was becoming increasingly widespread across most of the region. Not only does our sense of wilderness derive from Adirondack roots; so does our sense of wilderness threatened—the earliest images of overcutting were to be found in engravings of Adirondack scenes published in magazines like Harper’s and The Atlantic in the 1870s and 1880s. As the well-to-do sports made their way to the popular hotels in the mountains and lakes, their rail cars and stagecoaches rolled past many scenes of heavy cutting.2 The indignation they expressed helped to create the conservationist clamor that eventually led to the creation of the State Forest Preserve in the 1890s.

But that was not the only new development. The downstate transportation barons who were making vast fortunes off the Erie Canal read the work of proto-environmentalist George Perkins Marsh, particularly his 1864 classic Man and Nature, which argued that denuding forested slopes changed the flow of water dramatically, leading to spring floods and summer droughts from eroded soils that could not hold rainfall. Such sentiments were strong enough in the last years of the nineteenth century for the state to add an article to the state constitution holding that all state-owned lands within the park will remain “forever wild,” never to be cut or otherwise disturbed. It was the most forthright ecological action a political body had ever taken, or would take again for three quarters of a century.

The constitution couldn’t protect the half of the park still in private hands, however. And in the 1960s, as new construction of vacation homes began to threaten the region, a coalition of the remaining members of the rich old families and advocates of the emerging ecological movement combined to try to prevent the fragmentation of the Adirondacks. With the backing of Governor Rockefeller, they forced through the legislature a new set of regulations governing private land in the park, and setting up a commission, the Adirondack Park Agency, to administer the new zoning map. The APA was immediately unpopular with the locals, who pointed out (correctly) that they had been given scant part in its creation, though its new rules would change the value of their land and the shape of their lives.

To some extent the new laws worked—the Adirondacks remain relatively free of the vast real estate development that has altered so much of the American landscape. They have also led to angry protests. During the late 1980s and 1990s the Adirondacks were fertile ground for the kind of extremist property-rights activism usually associated with the rangelands of the interior West. A few of those opposing restrictions on development were suspected of burning down the barn of at least one environmentalist; hundreds of protesters blocked traffic for hours on the main highway to Albany. Under such pressure, the state backed off from its plans to strengthen the zoning laws, and the whole complex conflict remained unresolved, pleasing no one.3

In some ways, the oddest thing about the Adirondacks on the verge of the twenty-first century is that their future is not set. Most American places, whether in Westchester or Yosemite, San Diego or the Brooks Range, have taken some recognizable shape. Iowa represents for us corn, and if we don’t completely wreck the climate, probably always will. But the Adirondacks have never been identified with any one activity, not with farming (after a generation of fighting rocks, freezes, and blackflies, everyone took off west in search of topsoil), or with mining, or with the dream of a vast, completely protected wilderness park. Instead, the region remains a place very much like some other parts of the world—the vast expanses of Africa and South America—that are simultaneously wild and peopled. That makes it extremely valuable—conservationists from around the globe come here regularly now to see the only longstanding model of what they are trying to create elsewhere, “ecological reserves” that make it possible for people and nature to make a living in more or less the same place.

That possibility will be greatly enhanced if Pataki continues to maintain his recent position. Not only does the state need to make sure that the 350,000 acres of land now on the market end up either in the Forest Preserve or governed by easements that prevent subdivision but allow forestry; Pataki also must make economic development easier for the region. At the moment, the state’s Department of Economic Development divides the park into three sections, each of which is lumped with more populous regions to the south, north, and west of the Adirondacks. Environmentalists and local officials have been urging a different approach, one that would concentrate on bringing both business and tourism inside the Blue Line. The park’s population is so small that even a few million more dollars added to the region’s Community Investment Fund, a local development bank, would yield impressive changes. And the state should promise to reimburse local governments for the tax money they lose under state laws designed to benefit major timber producers.

Equally important, however, the people of the Adirondacks need finally to begin taking more control of their own future, instead of relying on the ideas of outsiders—the “flatlanders.” At the moment, much of the identity of Adirondackers comes from their working up resentment at outsiders. For the park to prosper in the next century, that resentment has to turn into something more useful.

Last year, for instance, an outside group, Defenders of Wildlife, proposed to reintroduce wolves into the park. The last wolf howled over northern New York a hundred years ago. They had been systematically exterminated for decades; some years the wolf bounty was among the biggest items in local town budgets. But though simple justice for wolves (not to mention maintaining the ecological balance of the region, or the tourist economy) argues for their return, such outside interference was, predictably, greeted initially with disdain. “I don’t know much about it, but I’m sure we’re against it,” said one local politician.

Ten years ago that might have been the end of it. But things have begun to change a little. Paul Smith’s College, for instance, formerly a modest two-year college which will next fall become the first four-year college in the park, helped form a citizen’s commission to consider the case for bringing back wolves. It includes everyone from environmental groups to trappers to local businesses, and they have been drawing up questions about wolves for biologists to answer. Imagine a region the size of Massachusetts without a single four-year college—without a place for its people to think about how they live. Paul Smith’s (of which I am a trustee) now calls itself the College of the Adirondacks, and its emergence is one of the more promising signs for the park’s future. (Both Pataki and the veteran state senator Ronald Stafford have promised large-scale state aid to turn the college’s library into a regional information center, redressing another major need of the park.) Imagine, too, a political entity the size of the Adirondacks without its own newspaper, its own TV station, without any shared source of news. But that may be changing too—North Country Public Radio has finally located enough relay stations on mountaintops to serve almost the entire park, the first time any journalistic organization has served all Adirondackers.

Those institutions, and others like them, will be crucial if the Adirondacks are to offer yet another possibility to the world: as a place that is both settled and wild, where people have exercised restraint as well as dominion, and made decisions for other than economic reasons. A place, moreover, whose citizens have decided that the view from the top of Blue Mountain enriches their lives more than a mall does. The Adirondacks, one hundred and fifty years after it exploded into the national consciousness, is the setting of one of the country’s two or three most exciting conservation stories—and most difficult and delicate ones as well.

—January 8, 1998

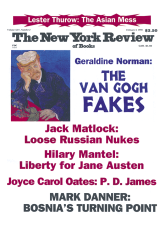

This Issue

February 5, 1998

-

1

See her The Great Forest of the Adirondacks (Utica: North Country Books, 1994).

↩ -

2

As Barbara McMartin makes clear in her The Great Forest of the Adirondacks, large parts of the park’s forest were not so completely devastated, at least before the turn of the century; and indeed in many places the logging was more gentle than has long been believed, resulting in large patches of old-growth or near-virgin forest.

↩ -

3

Catherine Henshaw Knott’s Living with the Adirondack Forest, which will be published in March by Cornell University Press, provides much useful data on these controversies, as well as many good interviews with Adirondackers.

↩