1.

Of the three towering figures in Spanish painting—Diego Velázquez, Francisco Goya, and Pablo Picasso—Goya seems to have a special appeal for imaginative writers. Too little is known of the life of Velázquez, Goya’s seventeenth-century idol. Velázquez has, as Robert Hughes notes, “next to no personal myth.” Of Picasso, whose Guernica owed so much to Goya’s searing depictions of war, we know perhaps too much; the sheer weight of the facts impedes our power to give them meaningful shape. It is difficult for us to feel the intimacy with these imposing artists that we do with Goya, who seems, though he worked two centuries ago and died in 1828, to combine accessibility and mystery, tradition and modern sensibility, in his person and in his pictures.

That mystery as well as the rich variety of Goya’s work accounts for sharp differences among the writers who have written about him. Goya spent his last years in exile in France, and through the nineteenth century it was the French who took the most interest in his work. For the Romantic poet Théophile Gautier, Goya was the quintessence of Spanish flair, a debonair connoisseur of bullfights and dark-eyed courtesans. For Baudelaire, by contrast, Goya was an alienated peintre maudit, a brooding painterly counterpart to that French invention “Edgar Poe.”

Goya’s series of etchings depicting Napoleon’s occupation of Spain, known as the Desastres de la guerra, or Disasters of War, was published posthumously in Paris in 1863, just as Mathew Brady’s photographers were fanning out across the killing fields of the American South to add their own deadpan horrors to Goya’s numbing record. From 1937—when the Goyas in the Prado Museum in Madrid were shipped to Geneva for exhibition and safekeeping during the Spanish Civil War—to 1945, no artist spoke more poignantly to European writers (not to mention such painters as Picasso and Robert Motherwell) of the disasters of war than Goya. André Malraux, Simone Weil, Ernest Hemingway—all testified to Goya’s disturbing prescience.

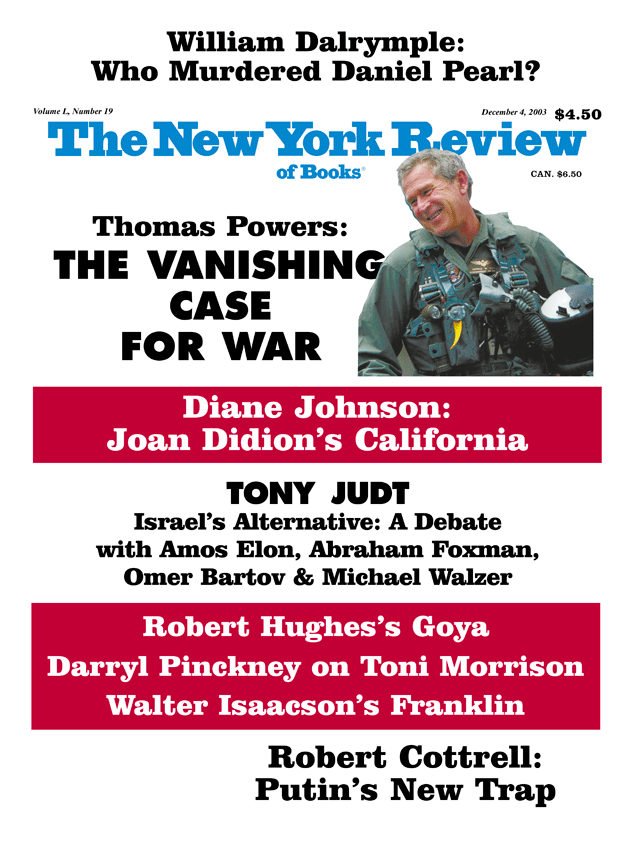

Lately, we seem to be in another Goya moment. During the past two years, the novelists Julia Blackburn and Evan S. Connell have written books about Goya’s life.1 The Goya of the Desastres is the presiding spirit in Susan Sontag’s study of visual representations of atrocity in wartime, Regarding the Pain of Others; “With Goya,” writes Sontag, “a new standard for responsiveness to suffering enters art.”2 Last year there was a perceptive exhibition on Goya’s images of women, curated by the Goya scholar Janis A. Tomlinson, at the National Gallery in Washington. The sumptuous Manet/ Velázquez exhibition at the Met this year, to which Goya was as central as Velázquez, added considerably to our understanding of Goya’s decisive influence on French and American realist painters.

Now we have Robert Hughes’s intensely written and powerfully imagined critical biography, a book that gives the impression of muscling the competition off the shelf. Hughes, for twenty-five years the chief art critic at Time magazine and the author of two marvelous evocations of place, Barcelona and The Fatal Shore (a history of his native Australia), among other books, reminds us that Goya is a writer’s painter, who saw an intimate tie between literature and his own incisive art. In an advertisement for the Caprichos, his etched fantasies of witches, prostitutes, and priests, Goya wrote:

The author is convinced that it is as proper for painting to criticize human error and vice as for poetry and prose to do so, although criticism is usually taken to be exclusively the business of literature.

That no painter in the history of art has criticized human error and vice more powerfully than Goya is a central claim of Hughes’s book, as is his view that Goya’s critical temper was key to his modernism. “We see,” Hughes writes, “his long-dead face pressed against the glass of our terrible times, Goya looking in on a world worse than his own.”3

Francisco Goya was born on March 30, 1746, in the remote village of Fuendetodos, a “hole” then and now, according to Hughes, amid “a landscape of deprivation where every stone is a sharp, weighty noun.” He spent his childhood in the nearby city of Zaragoza (Saragossa), the capital of Aragón made famous in accounts of the Gothic horrors of the Spanish Inquisition. Goya’s father, a professional gilder of Basque descent, supported the family by applying gold leaf to candlesticks and picture frames. His better-bred mother was of the lower nobility, as Hughes remarks, “that perhaps most useless rung of eighteenth-century Spanish society,” which entitled her to little more than the honor of being addressed as “Doña.” Little is known of Goya’s early education, which Hughes in any case finds of less importance than Goya’s “masculine pursuits” in the bleak landscape of Aragón, pursuits made possible by his uncertain social status:

Advertisement

He liked the macho life. He was good at it, and good company in the field. He was not cut out simply for the drawing room. Because he was not particularly a man of breeding, nor really a caballero, the hunt was also his way of connecting with the life of the nobles and royals he would need to serve if he were to get on. You didn’t need to be the Duke of This or That to hit a partridge, or to blaspheme victoriously when a puff of dust flew from its ass and it came pinwheeling down, feathers awry, out of the hard hot blue air.

We have better information about Goya’s training as an artist. At thirteen he was apprenticed to a local painter in Zaragoza, copying prints and learning the elements of design; in 1773 he married the sister of a fellow apprentice. Goya mastered the cherub- and-clouds rhetoric of eighteenth-century Rococo religious painting, traveled to Rome, entered—and lost—a few painting competitions, and returned to Spain, ambitious but still professionally adrift. In 1775, at the age of twenty-nine, he was summoned to Madrid by the Neoclassical court painter Anton Mengs to work at the Royal Tapestry Factory, thus launching his career as an artist in the employ of Spanish kings. After years of slogging work designing tapestries, Goya was promoted in 1789 from court painter to King Carlos IV’s pintor de cámara, the most prestigious post in the country for an artist.

Hughes knows that the most important events in an artist’s life involve the making of art; he doesn’t try to fill in the blanks of Goya’s early life with the sediment of legend and hearsay that was later to accumulate. Was Goya’s marriage a happy one? The most that can be said is that the marriage “lasted without incident or scandal for thirty-nine years.” Did Goya share a house with Piranesi during his youthful sojourn in Rome? It would be nice to think so, but the undoubted impact of Piranesi’s fanciful prisons on Goya’s depictions of madhouses far outweighs whatever we might make of possible chance encounters between them. The important thing, for Hughes, is to get at what in Goya’s temperament and times contributed to his utter distinctiveness as an artist.

In Hughes’s view, two upheavals—one in Goya’s personal life and one in the national life of Spain—made Goya the artist he was. Hughes writes more powerfully about these matters than anyone else has done before him. According to Hughes, Goya was temperamentally “averse to risks, physical or professional.” Though Goya (like Hughes) had a pronounced taste for the popular art of bullfighting, and portrayed himself dressed as a torero, he was “in no sense the conventional Spaniard—all cape, sword, and olés—imagined by nineteenth-century writers.” Goya’s roots were in the common people, or pueblo, but his political instincts impelled him toward the more progressive ilustrados, or “enlightened” class. “Enlightenment” was a relative term in Spain, to be sure, not to be equated with the ideas of Diderot and Voltaire: “Everything that had convulsed and remade European thought in the eighteenth century stopped at the Pyrenees.” But under Carlos III and his son, Carlos IV, who assumed the throne in 1788, the Inquisition, at least, had waned; and a painter like Goya with progressive tendencies could thrive in the Spanish court.

Having achieved a comfortable living, Goya, if he wished, might have gone on turning out religious paintings of modest originality and superb commissioned portraits, in which one can discern an edge of melancholia, but nothing more. A good example of the latter is the exquisite portrait of Don Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zúñiga, circa 1790s (at the Metropolitan Museum), the four-year-old son of one of Goya’s rich patrons. The alert little boy in a red suit with silver sash holds his pet magpie on a string, while three cats in the looming gray-green background look on with sinister intent, and a meticulously painted green cage of finches provides additional distraction for the cats and the viewer. The magpie holds Goya’s calling card in its beak. In this beguiling painting Hughes discerns “Goya’s awareness of how contingent life is: how at any moment, without warning, death can break into it.”

Death almost broke into Goya’s life in late 1792, when he was forty-five. A severe illness that might have been polio, syphilis, or meningitis, with alarming symptoms ranging from vertigo to hallucinations and partial blindness, nearly killed him, and left him permanently deaf. According to Hughes, there were signs even before this crisis that Goya, depressed and bored with his recent designs for tapestry, was looking for a new direction in his art. In an official report on the teaching of art, Goya maintained that “there are no rules in painting,” and argued that the bold naturalism of Velázquez would yield better art than the “monotonous manner” of Mengs’s copying from Greek statues. The illness and long recuperation that followed seemed to give Goya permission to experiment, and to trace the contours of his own bleak moods. In a series of small pictures—of bullfights, inmates in insane asylums, shipwrecks—he unraveled what Hughes calls “the long thread of violence and fear that would henceforth run through his work.”

Advertisement

There is also a new sexual frankness in Goya’s work of the mid-1790s. His passion for the Duchess of Alba, with her Cher-like shock of black hair and her “woman-of-the-people maja drag,” dates from these years. “Goya felt her sexuality,” writes Hughes, “with the uncensorable instinct of a hound getting a scent.” Two centuries of gossip have turned them into lovers. In the full-length portrait in the Hispanic Society in New York, she points to the words Sólo Goya traced in the sand. But according to Hughes, this is “Goya’s fantasy, not hers.” She may have been “rather an airhead,” Hughes writes, but

she was emphatically not a fool, and it would have been distinctly foolish to carry on an affair, even with a deaf and aging houseguest, in front of the numerous and no doubt inquisitive and chatty maids….

Nor, alas, was the duchess the model for the naked and clothed majas, which many years later got Goya into some mild trouble with the Inquisition. These striking portraits of a reclining maja (a sophisticated female counterpart of the majo, or Spanish dandy) are, for Hughes, a Spanish Olympia with remarkable modern qualities, in which, in the words of the art historian Fred Licht, Goya “divorces sexuality from love.”

The series of etchings known as the Caprichos, begun during Goya’s convalescence and published in 1799, hint at his future art; yet they still express the spirit of the Enlightenment. The famous plate once intended as the title page, which Goya moved to the middle of the series, shows a Goya-like intellectual asleep at his desk, surrounded by cats and bats and a clear-eyed lynx. The caption, “El sueño de la razón produce monstruos” (“The sleep of reason produces monsters”), is ambiguous: sueño can mean “sleep” or “dream,” and it is unclear whether Goya means that the absence of reason breeds monsters or that reason is itself a kind of sleep. But Goya’s lacerating dissections of marriage (husband and wife joined at the back) and prostitution, witchcraft, and the priesthood imply the faith of an ilustrado, or enlightened person, in the artist’s ability to expose hypocrisy under the guiding light of reason.

It is tempting to find the same corrosive spirit in Goya’s great group portrait, painted the following year, of The Family of Carlos IV, in which Goya paints himself (in the manner of Velázquez in Las meninas) in the shadows at his easel while a harsh light plays across the remarkably ugly features of the royal family. In his biography, Connell quotes Hemingway’s view that the picture was “a masterpiece of loathing,” but Hughes finds no evidence of “satirical intent” and suggests that “it may even be that Goya made the royal couple look somewhat nobler and more handsome than they did in real life.” The portrait is, in Hughes’s view, “an excited defense of kingship: not its divinity, to be sure, but what later ages would call its glamour, its ability to bedazzle the commoner and the subject.”

That illusion of stable, somnolent glamour was about to be shattered. If Goya, in Hughes’s formulation, was “the last Old Master and the first Modernist,” one might regard The Family of Carlos IV as Goya’s final Old Master painting. The sclerotic administrative structure of the Spanish court and the festering family rivalries between the King and his resentful and reactionary son, Ferdinand, were vulnerable to foreign intrigues. Napoleon, who crowned himself emperor in 1804, made a shady deal with the Spanish throne for the partition of Portugal, but the tens of thousands of French troops that poured into Spain remained there to capture the real prize, Spain itself. When the Spanish public realized that Madrid was in foreign hands, there was a patriotic uprising, culminating in the events of May 2, 1808, when Spaniards rampaged through the streets slaughtering French soldiers and sympathizers. The following day, French troops put down the rebellion and restored order, with mass executions in public squares. On June 6, Napoleon placed his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, on the Spanish throne as José I, and a new constitution was quickly drawn up for the “liberated” country.

The traumatic days in May, commemorated in two of Goya’s most powerful paintings, were the beginning of the Spanish War of Independence, known by the French and English as the Peninsular War. The familiar twentieth-century practices of “guerrilla” (or “little war”) conflict and underground resistance date from that war, which raged until Wellington’s decisive victory over the French in 1813. Goya’s political perspective on this second upheaval in his life was complicated and nuanced. His pendants of The Second of May and The Third of May, apparently never shown during his lifetime, express a straightforward patriotism exacerbated by his choice of Arab Mamelukes, in the first picture, to portray the French forces under attack. The struggle “between true-blue Spaniards and bloodthirsty foreign Moors” invoked, according to Hughes, the residual Spanish “anti-Arabism” dating back to the Crusades.

The more familiar Third of May is also more modern, with its lantern-lit, white-shirted victim, hands outstretched as in a Crucifixion, confronting the machine-like firing squad, whose faceless inhumanity is enhanced by our seeing them from the back. Manet’s appropriation of the image for his Execution of the Emperor Maximilian of Mexico (1867) is well known; Hughes adds the interesting suggestion that the lightbulb in Picasso’s Guernica, “emblem of the pitiless glare of twentieth-century awareness,” derives from the “fierce cubical lantern shedding light on Goya’s execution scene.”

But were Goya’s views of the French occupation really so straightforward? Many of his closest friends welcomed the French invaders as instruments of liberal reform long needed in Spain. It was easy to protest the brutal executions of the third of May; it was harder to wish for the return of the often benighted Spanish kings. And brutality was hardly the monopoly of the French. One of the most remarkable things about Goya’s extraordinary etched record of guerrilla warfare in Spain, the Desastres de la guerra, is how evenhanded he is in the apportioning of blame. Both sides indulge in unspeakable acts. “No se puede mirar” (“one cannot look”) is one of Goya’s captions. The noosed man hanging from a too-small tree, while French soldiers yank at his legs, is undoubtedly a Spanish patriot. But the representatives of the Populacho (“Mob”) who are driving a sickle blade into the exposed anus of a French sympathizer are just as undoubtedly Spanish patriots. Images of straightforward heroism, such as that of the woman firing a cannon while standing on a heap of male corpses, are rare in the Desastres. It is their open-eyed disillusionment that gives them their modern quality. “He was the first painter in history,” Hughes argues,

to set forth the sober truth about human conflict: that it kills, and kills again, and that its killing obeys urges embedded at least as deeply in the human psyche as any impulse toward pity, fraternity, or mercy.

We may wonder where Goya found inspiration for the starkly simple visual means of the Desastres, and here I believe Hughes has committed a slight injustice. Hughes praises the looming backgrounds of Goya’s etchings (“those deep, thick, mysterious blacks against which figures appear with such solidity and certainty, and yet with such apparitional strangeness”), the jarring contrasts of light and dark, and the “geometrical severity of Goya’s composition,” as in the circular cannon wheel juxtaposed with a pyramidal distant hill in the plate I have just described. Such devices, he observes, are “as Neoclassical as David.” This aside reminds us that in Goya’s life there was a third upheaval—in addition to his near-fatal illness and the French invasion—which also had a decisive bearing on his distinctiveness as an artist. Goya’s apprenticeship coincided with a seismic shift in European aesthet-ics. In Spain, as in the rest of Eu-rope during the last quarter of the eighteenth century, there was a profound change in taste, as the frivolously sensual Rococo yielded to the severe and moralizing tenets of Neoclassicism.

The most influential figure in Spanish art during Goya’s rise was the Bohemian painter and committed Neoclassicist Anton Raphael Mengs, lured to Spain from Italy by Carlos III. It was Mengs, in turn, who presided over Goya’s rise in the King’s stable of artists. Mengs’s work, wildly popular in his time, is hard to like today. But Hughes is unduly harsh in his treatment of Mengs, whom he regards as the very opposite of the macho ideal:

Stolid, correct, devoid of charm, insipid where strength was needed, dogmatic where fancy might have helped, thumped into shape as a “prodigy” by a failed-artist father and relentlessly promoted by the theorist of Neoclassicism, Winckelmann, whose leaden flights of pederastic dogma make even the longueurs of modern “queer theory” look almost sprightly—Mengs was one of the supreme bores of European civilization.

Hughes prefers to think that the aging Tiepolo, also briefly in the royal employ of Carlos III, had more influence on Goya, and he notes superficial resemblances between the Caprichos and Tiepolo’s work in a similar vein.

No one was more responsible than Mengs, however, for clearing away the cluttered accretions of Rococo art. Mengs and his close friend the German aesthetician Johann Winckelmann (whose ideas also influenced David) were the leaders of what Hugh Honour calls the “early, negative anti-Rococo phase” of Neoclassicism.4 In their search for what Winckelmann called “noble simplicity and calm grandeur,” they shied away from bright colors and the illusion of deep recesses, preferring a frieze-like arrangement of seemingly sculpted figures in schematic patterns. In the Caprichos, and even more powerfully in the Desastres, Goya turned idealizing Neoclassicism on its head, giving its schematic machinery and severe structures (meant to suggest a utopian order) the inevitability of nightmares.

Hughes admires “Goya’s singular ability to stabilize scenes of violent action by making them into a framework of almost Neoclassical rigidity,” but he can’t bear to acknowledge that Goya might have inherited this “framework” from his patron Mengs. The mutilated body parts hung on a tree in the thirty-ninth plate of the Desastres are, as Hughes astutely observes, “a sickeningly effective play on the Neoclassical cult of the antique fragment.” (Evan S. Connell also writes of “bloody human limbs stuck on tree branches like fragments of marble sculpture.”) But Hughes’s gratuitous remark, that “if only they had been marble and the work of their destruction had been done by time rather than sabers, neoclassicists like Mengs would have been in esthetic raptures over them,” serves to obscure rather than clarify Goya’s debt to Mengs.

2.

If two disasters give shape to Hughes’s narrative of Goya’s life, part of the uncanny power of his book arises from parallel disruptions, one private and one public, in Hughes’s own life, which he relates directly to his understanding of Goya’s life and art. Hughes’s private disaster, a counterpart to Goya’s deafness, was his near-fatal car crash in 1999 on a desert highway in western Australia that smashed his body “like a toad’s,” and left him in a coma for five weeks. During much of that time, Hughes writes, he dreamed of Goya, who came to him dressed like a bullfighter, as in his 1794–1795 self-portrait (see illustration on page 6), and jeered at Hughes for presuming to write about him—Hughes’s plans for a book on Goya had stalled long before the accident. In his moving opening chapter, “Driving into Goya,” Hughes describes the sense of release he felt after the accident, as though he had to “crash through” his writer’s block. “It was through the accident,” Hughes writes, “that I came to know extreme pain, fear, and despair; and it may be that the writer who does not know fear, despair, and pain cannot fully know Goya.”

The national disaster that haunts Hughes’s book, and provides a parallel with the horrors of the Peninsular campaign in Spain, is the Vietnam War. “The main reason that I started thinking about Goya with some regularity,” he writes,

lay in the peculiar culture whose tail end I encountered when I went to live and work in America in 1970…. Here was America, riven to the point of utter desolation over the most bitterly resented conflict it had embarked on since the Civil War. Vietnam was tearing the country apart, and where was the art that recorded America’s anguish?

Like Simone Weil and André Malraux before him, Hughes found nothing more powerfully representative of the horrors of twentieth-century war than what Goya had created two hundred years earlier: “There was nothing, absolutely nothing, that came near the achievement of Goya’s Desastres de la guerra.”

In a book that is sometimes combative in tone and judgment, Hughes writes with quiet sympathy of Goya’s final years, a period of increasing exile for the aging artist. The restoration of the king, Fernando VII, was a disaster for Spain, which devolved into a medieval wasteland of violent repression, recrimination against anyone suspected of liberal views, and a resurgent Inquisition. Stone-deaf and disillusioned, Goya moved first in 1819 into a farmhouse on the outskirts of Madrid, known coincidentally as the Quinta del Sordo, the estate of the deaf man, for a previous owner. He painted the plaster walls with a phantasmagoria of his own private obsessions: Saturn devouring his son (or perhaps daughter); a witches’ sabbath; two peasants, knee-deep in muck, beating each other with cudgels; a little dog alone on a hillside looking mournfully upward. What do they mean? “We do not and cannot know,” Hughes answers, though he suspects that the escalating terror in Spain may be behind some of them.

In 1824, Goya fled across the border for his final exile, in France. It is painful to imagine the seventy-eight-year-old artist, who knew no French and couldn’t have heard it if he did, wandering unknown through the streets of Paris. (The young Delacroix, already an intense admirer of Goya’s prints, knew nothing of his idol’s presence in Paris.) After settling in Bordeaux among fellow exiles, Goya drew the damaged humanity he had witnessed on his wanderings: an old woman in a cart being pulled by a harnessed dog (“Yo lo he visto en Paris,” “I saw this in Paris,” he scrawled across the paper), and a legless beggar on an improvised wheelchair. Goya himself felt maimed. In late December 1825, he apologized in a letter to a friend for his bad handwriting. “I’ve no more sight,” he wrote, “no hand [poigne], nor pen, nor inkwell, I lack everything—all I’ve got left is will.” Toward the end of his life, there was a final surge of creativity—tiny paintings on ivory, deftly comic drawings, etchings—when Goya, as Hughes says, was “truly off on his own now, making for making’s sake, on the tiniest of scales.” Nowhere is that sense of defiant release more palpable than in a late drawing of a grinning old man on a swing, “like a Zen patriarch,” Hughes notes, “absorbed in a private but cosmic joke: Goya himself, high in the air.” Goya died of a stroke on April 16, 1828, at the age of eighty-two.

This Issue

December 4, 2003

-

1

See Julia Blackburn, Old Man Goya (Pantheon, 2002) and, to be published in February 2004, Evan S. Connell’s Francisco Goya (Counterpoint). ↩

-

2

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003, p. 45. ↩

-

3

Robert Hughes, “The Unflinching Eye,” The Guardian, October 4, 2003. ↩

-

4

Hugh Honour, Neo-Classicism (Penguin, 1968), p. 32. Mengs’s understated portrait of Winckelmann reading the Iliad (circa 1768) is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. ↩