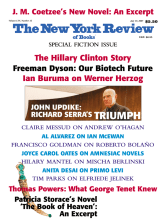

No doubt about it, the show is a triumph, the biggest interactive art event in Manhattan since Christo’s saffron flags fluttered in a wintry Central Park over two years ago. The day your reviewer attended Richard Serra Sculpture: Forty Years, a sunny Monday in June, the two large sculptures in MoMA’s Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden were crowded with young families, small children, and hopeful couples negotiating hand in hand the narrow passageways of Intersection II (1992–1993; see illustration on page 18) or jollily huddling in the crescent of shade inside the sun-baked interior space of Torqued Ellipse IV (1998).

The holiday, playground atmosphere surprised me, armed with a notebook and steeled, so to speak, to cope manfully with towering masses of metal and the great weight of art-historical importance that more timely reviewers had already assigned to the sculptor and his displayed works (“Not only our greatest sculptor but an artist whose subject is greatness befitting our time”—Peter Schjeldahl; “A landmark, by a titan of sculpture, one of the last great modernists in an age of minor talents, mad money and so much meaningless art”—Michael Kimmelman). Indeed, I was so intent on properly absorbing these marvels that I tripped over a stray toddler and nearly booted him into the rectangular, mercifully shallow pond at whose edge MoMA has posed Aristide Maillol’s silvery nude statue The River. This beloved allegorical figure, by the way, is the only customary resident of the Sculpture Garden who has not been swept away from his or her spot by the invasion of Serra’s big steel; even the trees, especially a feathery sweet locust inches from a jutting angle of Torqued Ellipse IV, look intimidated.

Surprising, too, was the wealth of textural incidents with which the twelve-foot walls of weatherproofed steel are spectacularly marked, or marred. On the two pieces outdoors in the Sculpture Garden, the weatherproofing, a brittle bluish film, is more worn off than not; lichenous orange blooms of rust have proliferated, and long rivulets of moisture have left ruddy rippling tear-trails down the slant surfaces of two-and-a-half-inch steel. Their basic coat of rust is a velvety reddish brown and looks fuzzy and eerily weightless compared with, say, David Smith’s rather implacable welded constructions—those squarish slabs of circularly burnished bare metal—and Anthony Caro’s riveted, sometimes gaudily painted beams and industrial fragments.

Serra’s early artistic training, at the University of California at Santa Barbara and then at Yale, was in painting: the fittingly massive catalog Richard Serra Sculpture: Forty Years (it accompanies the show but contains photographs of many more works than are in it) prints a conversation with the MoMA curator Kynaston McShine in which the sculptor recalls, “I ended up in my last year painting something that looked like, oh, renditions of Abstract Expressionism, somewhere between Pollock and de Kooning.” To another interviewer he has confided, “I was no slouch as a painter,” and pointed out “that he beat classmates Chuck Close and Brice Marden to a Yale traveling fellowship.” (Nor is he a slouch at theorizing; he says himself, “I came up with a generation of artists who wrote…. We had a need to write about the issues involved in our work and we wanted to encourage critical dialogue. My generation dealt with analytical language more than generations that had come before or for that matter after.”)

Surveying the many square meters of curved steel, one encounters passages of flaking waterproofing that resemble the flaky vertical canvases of Clyfford Still, and other sections as luminously blobby and drippy as oils by Sam Francis. The striped stains of Morris Louis also come to mind. One would like to know how many of these picturesque effects were the blind work of weather and accident (bumptious youngsters have left dusty sneaker-prints on lower portions of Torqued Ellipse IV and the giant crane that lifted it over the garden wall from 54th Street left marks of its clamp at the top) and how many, if any, were induced by the sculptor. Certainly Serra was not above leaving chalked numbers, Pop-style, on some of his steel plates—see the prominently displayed assemblage Five Plates, Two Poles (1971) in the East Wing of the National Gallery of Art in Washington—and a number of parallel shadows in the larger pieces at MoMA do seem more than accidental.

In any case, how do the visual stimulations of these two outdoor pieces differ from those to be obtained by walking around a shipyard where some weary freighters have come to rest? A determinedly industrial art like Serra’s risks confusion with the products of industry themselves. What impressions do they offer unobtainable by a sensitive observer in a railroad yard, or underneath a highway overpass, or at the mouth of a tunnel? There, the scale is greater than any that can be matched by a lone artificer, and the sensations even more dizzying, if dizziness is the desired effect. Passing from the sixth-floor portion of the Serra exhibition, one can gaze down the depth of the museum’s atrium, to the people-speckled second floor and the foreshortened top of Barnett Newman’s rusted-steel sculpture Broken Obelisk (1963–1969), for a truly visceral sensation of depth and volume. Art can never overtop reality’s dimensions. To be sure, rusty freighters can be viewed aesthetically, especially if the observer is Joseph Conrad or the Colombian writer Álvaro Mutis, whose own experience of shipping had redolences of the distances and hazards of the sea and the fog-shrouded gallantry of seafarers.

Advertisement

Serra’s rusty slices of grandeur, however, awakened in me nagging worries about how the German steelmakers precisely warped such vast plates, and how much the process cost, and who paid, and how the cumbersome products were packaged and transported. Mysteries, to be sure, but perhaps not fruitfully mysterious. The giant Serra book ignores them; besides the adroit and charming interview with Serra it contains weighty philosophical/topological/ontological essays on Serra’s earlier work, his “abstract thinking,” and his sculptures in landscape, by Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, John Rajchman, and co-editor Lynne Cooke respectively, but almost no concrete information about how the works were made. Serra seems to hand cardboard models to a German foundry, and out pop the ten, or twenty, or hundred tons of properly bent steel.* He told Charlie Rose in a telelvision interview that no steel company left in this country can handle the job. Everything except the words manufactured about the sculptures is produced offshore.

The sixth floor displays the works, from the late Sixties to the mid-Nineties, when torqued (a computer-enabled advance over merely curved) steel became his métier. He began as a child of Pollock, hurling hot lead from a ladle against the base of a wall and hanging on the wall tangles of rubber belting. In a bygone New York of low rents and serendipitous trouvailles, “a rubber warehouse was emptying out on West Broadway,” as Serra tells it, “and I phoned the manager of the company and asked if I could cart the rubber away.” For someone with Serra’s theoretical bent, rubber was a boon: “It has a flexibility,” he says, “that allows you to readily deal with line, plane, volume, and gravity. It delivers potential to your fingertips.” He realized one sculptural masterpiece with it: To Lift (1967), named from a long list of procedural verbs (to roll, to crease, to twist, to lift, etc.) that he drew up to jump-start his career, is a powerfully ominous hood or tent shape created simply by lifting up one edge of a thick sheet of vulcanized rubber in the center and letting it stand.

A stunt of sorts, it was followed by various gravity-defying sheets and tubes of lightly rolled lead leaned in such a way to be mutually supporting (Floor Pole Prop, 1969; Shovel Plate Prop, 1969). The arrangements became more elaborate and free-standing, eye-teasers with a nod to Op Art; massive yet precarious-looking, four are enclosed on MoMA’s sixth floor in a low plexiglas wall, presumably to protect them from a toppling touch by the same urchins who left sneaker prints on Torqued Ellipse IV. The pieces are as defiant of gravity as their titles are cryptic: 5:30; 1-1-1-1, One Ton Prop (House of Cards); V+5: To Michael Heizer, all from 1969. Lead has the virtue of being almost as easily worked as cloth (Folded, Unfolded, 1969), but outdoor projects led Serra to the tougher medium of steel.

In 1970, the year when he worked with his friend Robert Smithson in staking out Smithson’s renowned earthwork Spiral Jetty, Serra won a grant for an urban earthwork in the Bronx: “I found a dead-end street at 183rd and Webster Avenue and built a steel circle flush with the asphalt.” In a photograph of the seedy site, amid cracked paving, parked cars, and drifts of street trash, the half-flanged ring, its diameter of twenty-six feet stretching nearly curb to curb, has a certain unearthly beauty—a halo left behind by an oversize visiting angel. The volume accompanying the exhibition holds photographs of many other site installations, some almost swallowed by the land whose contours they emphasize, and others, like the ill-fated Tilted Arc (1981) in Manhattan’s Federal Plaza, all too dominant of their environment. Tilted Arc made the news when office-workers from nearby buildings protested that their space for lunch and leisure had been brutally cut in half by the great dark wall of weatherproofed steel, which was finally removed or, as its listing rather indignantly puts it, “Destroyed by the United States Government, 1989.”

Though such aggressive scale defies museum capacities, Serra’s brutalism is well enough represented on the sixth floor by the two giant plates of Delineator (1974–1975), one on the floor and the other, at right angles to it, stuck on the ceiling, and by the four stark plates of Circuit II (1971–1984), taking up the whole, from center to corners, of the considerable room that holds them. As MoMA’s handout pamphlet states, Circuit II “sets up a new environment for the viewer, who is forced to move through the spaces created by the work.”

Advertisement

This curious idea, of forcing the viewer to walk in a certain way, and achieving thereby a reformation or enhancement of his inner life, follows from Serra’s long-held antipathy to sculpture as the creation of visual objects. Duchamp, by presenting a urinal or bottle rack as a piece of art, made it “a fetish for display.” Worse and “most disturbing” to Serra, such display “retains the hierarchy of the object, and as a consequence art objects become life-style accessories.” Instead, the process of viewing is taken as central, just as the processes of lifting, rolling, bending, and splashing were central to Serra’s first ventures into art. As he disarmingly and epigrammatically admits of this fledgling era, “The residues of the activities didn’t always qualify as art.”

But the massive residues of his (and the German steelworkers’) activities in the new century, in his sixth decade, do so qualify. The new MoMA’s second floor, where an extra-high, extra-weight-bearing room was built specifically to house the massive constructions and installations of contemporary art, supports three of Serra’s recent masterpieces: Band (2006), a continuous wall winding through four loops, forming four nearly enclosed spaces; Torqued Torus Inversion (2006), two later, matched variations of the torqued ellipse in the sculpture garden; and Sequence (2006; see illustration on page 17), two intertwined S-shapes with a sinuous path between them. Sequence most remarkably and completely achieves Serra’s anti-pictorial program for sculpture; it can be walked through but not visualized, as even Band can be mapped in the mind’s eye. Serra explained to his interviewer Kynaston McShine:

At both ends you have the choice of entering through one of two openings. One will lead you to the containment of an interior space; the other will direct you into a seemingly endless path between two leaning walls. You cannot recollect or reconstruct a definite memory of the curvilinear path that connects one spiral to the other, nor of the interior spaces of the two spirals. You cannot map the piece after you’ve walked it.

So it was; two ambulations left me no wiser. The walls lean in and out above and around you, and other bemused wanderers are encountered in spaces now narrow (producing a mild anxiety), now wide (and peaceful, like an inner courtyard); but not even some vivid passages of varied rust, including pale patches like mildew, make it a primarily visual experience. In an attempt to see, as I moved through I let my eyes go out of focus and watched the angle of curved steel ahead of me change in an animated slow motion. As Serra says, “It feels as if you are being subjected to an accelerated gravitational pull.” John Rajchman’s essay “Serra’s Abstract Thinking” explains:

Serra’s abstraction is not an eidetic extraction from objects’ forms and shapes. It is experiential and experimental, a great machine that affects our bodies and brains directly, rather than “moving” us indirectly through what it represents.

The image of a machine recurs: “His works become gigantic steel exercises in thinking, great rusting machines in which the coordinates of natural or habitual perception are scrambled and undone—but in such a way that one exits strangely refreshed.”

The process could not be more sympathetically explicated. Only after one emerges from these ingeniously destabilized spaces does a question of disproportion arise. All this steel devoted to scrambling our habitual perceptions? Wouldn’t the funhouse or Ferris wheel at the country fair do just as well? Didn’t Cubism and Surrealism do it a century ago with little flat canvases’? These “great rusting machines” in their mightiness of weight and extent compare with the huge statues men have erected to Buddha, pharaohs, and, off Manhattan’s shore, the idea of liberty. In the absence of any content that would confirm a public in its ideology, the goal is—to quote the devoted Rajchman again—“a new sort of visceral intelligence,” “another kind of experience normally unavailable to us.” Is this objective enough for a form of art, large-scale sculpture, that is usually directed away from the purely private sensibility?

To reach the Serra show the museumgoer has to pass a tall wall covered with satirical graffiti, by the Romanian Dan Perjovschi, concerning the United States and its frivolous capitalism. As one of my fellow travelers through the Serra show asked, gesturing at the cunning, triumphal, and luxuriously grand artifacts around us, “Isn’t this capitalism?”

This Issue

July 19, 2007

-

*

The photographs of three of the large works completed in 2006 are captioned “Shown installed at Pickhan Umformtechnik GmbH, Siegen, Germany.” Kynaston McShine’s three pages of introduction include thanks to Pickhan Umformtechnik and Dillinger Hüttenwerke, Dillingen/Saar, for “their professional involvement in the making of the recent work.” The only detailed treatment of the making comes in the thirty-second footnote to Lynne Cooke’s essay on Serra’s sculptures in landscape, quoting a 1994 interview with Serra: “Basically, a forge is a hydraulic hammer which displaces metal under compression. It differs from casting in that in an equal volume, the cast will weigh one-third to one-half less than the forged work of the same measurement…. By using a magnesium and carbon steel, I found that its molecular structure, when heated to 1,280 degrees, was cubic. There was something very satisfying about dealing with a cubic structure to make a cube.” Of some outdoor blocks called Snake Eyes and Boxcars (1993), he says they “have an archaeological look in that they don’t look like steel, they look like stone. They have a burned quality like meteors or something. That has to do with the fact that we not only forged them but when they were cooling down we flamed them, so that there’s no mill-scale on them.” The “we” in “we flamed them” indicates Serra’s considerable involvement at the foundry level, and his satisfaction in molecular “cubic structure” shows a desire to dominate the process from the atomic level up.

↩