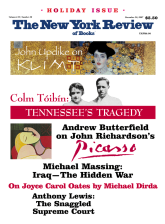

The Gustav Klimt exhibition, which opened on October 18, 2007, will fill the Neue Galerie until the end of June next year. Its attention-riveting center is Klimt’s 1907 portrait of the prominent Viennese society figure and art patron Adele Bloch-Bauer (see illustration), executed in oils, silver, and gold—a radiant example of his so-called Golden Style, which was inspired by the artist’s two visits, in 1903, to Ravenna, where he saw the Byzantine mosaics in the church of San Vitale.

He was especially taken, Renée Price tells us in her commentary on the painting, by the mosaic image of the Empress Theodora, “glittering before an abstract gold background.” These were “mosaics of unprecedented splendor,” he wrote to his friend Emilie Flöge. But Byzantine mosaics were not the only influences tugging this portrait toward decorative abstraction: Russian icons also embedded faces in a plane of gold; Egyptian art, which fascinated Klimt, is echoed in the hieroglyphic eyes dominating Adele’s strapped dress; and Japanese woodcuts, Janis Staggs writes in her catalog essay on Klimt’s relation to Emilie Flöge, “typically schematize the human body hierarchically: the face and hands are depicted with painstaking verisimilitude, whereas other physical attributes—as well as clothing and elements of nature—are rendered more abstractly.” Horizontal eyes and vertical half-moons in the sitter’s garments both suggest vaginas, indicating another of the painter’s interests and doing nothing to discourage persistent but unproven rumors of a romantic connection between the artist and his subject.

The main titillation, however, to the throngs that crowd the Neue Galerie’s marble stairs and exiguous spaces is perhaps less Klimt’s sexiness than Ronald S. Lauder’s extravagance; he paid $135 million to add the portrait to his collection and his museum, once the work had, over a half-century after its expropriation by the Nazis, been restored by a panel of Austrian judges to the Bloch-Bauer heirs. So Adele Bloch-Bauer’s portrait is by several reckonings a celebrity painting, bound to be the star attraction for years to come at the elegant little museum bestowed by the Lauder cosmetics fortune upon the corner of Fifth Avenue and Eighty-sixth Street.

Dazzling in the amount of gold and Geld lavished upon it, Adele Bloch-Bauer I (another portrait, less dazzling, followed in 1912) repels critical judgment. Does its subject’s lush, heavy-lipped, dark-browed, green-eyed face, beneath a black blob of hair and above a silver-encrusted collar, a pale stretch of upper chest, and a rather anxiously wrung pair of skinny pale hands, really mesh with the astonishing efflorescence of perspective-free patterns—eyes, spirals, squares, streaks, and splotches, ostensibly related to the wistful sitter’s dress, robe, and armchair? Or does she look like a decal stuck onto a collage of tinselly wrapping paper? A witty and surprising patch of green in the lower left corner represents, it must be, a floor—otherwise the Vienna socialite, twenty-six at the time of this portrait, would seem to have been transported, bodiless, to a giddy Heaven of teeming ornament. Is such an abrupt juxtaposition of textures—Klimt’s favored method in this decade, producing, most famously, The Kiss (1907–1908)—a bold and necessary step in the direction of modernism, or an uneasy half-step, a cheaply bought glamour, a kind of higher kitsch? The viewer looks around the room, with its mute watchmen of Wiener Werkstätte clocks, at the other six Klimt paintings on display, for orientation.

The Dancer (1916–1918), a much later, unsigned, and unfinished canvas that prior to the spectacular new acquisition was the museum’s featured Klimt, also holds a clash of textures, but, more roughly painted, in stabbing brushstrokes that testify to the painter’s struggles with portraits in his later years, seems to consist not of two distinct planes but of only one and a half. My gaze rested most comfortably, I found, on the near-monochrome The Park of Schloss Kammer (circa 1910), its pointillist mix of greens and blues flooding the large square canvas to the corners; the little, early, vertical Pale Face (1903), a study in black, cream, and mauve, the black insouciantly descending from bulky hat to flowing hair to dark coat without a break in its sinuous contour; and, earlier still, The Tall Poplar Tree I (1900), another dark shape reaching past the painting’s upper edge, against a radiant sky where bits of surreally sharp azure stare through the clouds.

All three paintings show the painter’s wish to banish perspectival depth—to confess, as it were, the flatness of the canvas—yet also respond to the stimuli of natural appearance: green dabs of motion in the foreground pond of the park; the sharp nose and long chin and meditative smile of the female contemplative, a café-haunter à la Toulouse-Lautrec; and the fuzzy saplings and dotted flowers in the orchard beneath the white sky, seen with Impressionism’s soft focus. These paintings have a settled peace, whereas the brazen, theatrical patterning of Klimt’s Golden Style, not to mention the hectically crowded symbols of his once-scandalous murals, have about them the nerved-up anxiety of fashion, which is always being pushed from behind by the next spectacular thing.

Advertisement

Fronting on Fifth Avenue, the former library holds a collection of photos and memorabilia indicating that Klimt—smartly bearded, increasingly high-browed—cut quite a figure in fin-de-siècle Vienna. He was a lifelong Viennese, one of seven children of an impoverished metal engraver from Bohemia, and a considerable womanizer, in an era when womanizing still had a good name. He never married, living with his mother and sisters, though one model/mistress, Marie (Mizzi) Zimmermann, bore him two sons around the turn of the century. He concentrated on easel painting only after the breakup of the Künstler-Compagnie, formed in 1883 by him, his brother Ernst, and Franz Matsch, their fellow student at the Technical School for Drawing and Painting, to decorate theaters and public buildings in, his catalog biography states, “the Historicist style, without stylistic differences, and with the allowance that one will take over another’s work, should they be unable to complete it.”

The breakup was hastened by Ernst’s death in 1892 and by “the stylistic evolution of Gustav.” His post-Historicist career was stormy, punctuated by academic resignations and critical vicissitudes. The critic Hermann Bahr wrote in 1899 of Klimt’s Schubert at the Piano that it was “the finest painting ever done by an Austrian…. I know of no modern that has struck me as so great and pure as this one” and four years later, in 1903, edited an anthology of hostile articles entitled Gegen Klimt (Against Klimt). Klimt relished the role of artist, posing, in photographs, like a priest, with Emilie Flöge or alone, in one of the loose caftans or robes called Reformkleider; a blue one worn by Klimt is on display, stitched with arcane symbols on the shoulders.

Farther along on the Eighty-sixth Street side, a dim chamber holds Klimt drawings from his student days on, almost all of them from the collection of the Galerie’s co-founder, the dealer and collector Serge Sabarsky. They reveal Klimt’s dark secret: he was a superb draftsman in the academic manner, a master of its most rigorous requirements. To become a modern, he had a great deal to unlearn. His two heads of a bearded man, in charcoal with white heightening, gleam with exactitude, from bald pate to gauzy hair-ends; his portrait, also in 1879, of a pre-adolescent girl is softer and more soulful. The two male nudes in pencil from the next year astound us with their photographic accuracy, especially the dramatically reclining pose, with its scrupulously detailed genitals and its startling burst of chin whiskers erupting on the horizon of the foreshortened chest.

By the mid-1880s, collecting visages and costumes for the cooperative murals of the Künstler-Compagnie, Klimt loosened up, sketching and shading with a professional dash. In a profile of a fat man (1897–1898) the slashing strokes of black chalk attained a studied fury. From the same years, the drawing ponderously titled Floating Female Nude in Front of Dark Background arrives at his mature eroticism. The nude is seen, in what will become a habitual point of view, from below, her pubic bush pushed forward in our gaze, her feet eliminated (hence the “floating”), and her belly, waist, breasts, and underarm arrayed in a series of waves that crest in her averted face, eyes closed as if she is ecstatic or drowned or about to be frontally possessed.

Upstairs, later drawings from Sabarsky’s extensive collection are hung in narrow corridors that give the jostling art-viewers, while Viennese waltzes and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony play in the background, a heated sensation of the illicit. Visitors to Klimt’s last studio, an “unadorned garden house” at Feldmühlgasse 11, which he occupied from 1912 until his death of a stroke early in 1918, reported an abundance of naked models, casually disposed in a “voluntary hermitage” that “friends rarely dared enter.” A female visitor, Berta Zuckerkandl, an artistically well-connected journalist who won Klimt’s confidence, said of his models that “there were always several of them waiting in the anteroom, so that he had a continuous and various supply of models available for the theme ‘woman.'” An unnamed visitor left a more specific account of the artist at work,

surrounded by mysterious, naked women who, while he stood silent before his easel, wandered up and down his workshop, sprawled, lazed about, and made the best of the day, always ready at a signal from the master to hold still obediently whenever he spotted a pose, a movement, that attracted his sense of beauty when captured hurriedly in a quick sketch.

To judge by the surviving evidence, there was a great deal of sprawling about, rear end foremost or thighs generously spread. Masturbation, in a supine position (Reclining Nude Facing Right, 1912–1913) or prone (Reclining Female Semi-Nude Facing Right, 1914– 1915), is a frequent theme; some of the more vivid adepts (Seated Woman in Armchair, circa 1913; Seated Woman with Spread Thighs, 1916–1917) are, but for their crotches, completely clothed, as if acting on a sudden inspiration. Marian Bisanz-Prakken, in her essay on the late allegorical works The Virgin and The Bride, delicately but confidently touches on the question of these models’ compliant exhibitionism:

Advertisement

With his sure instinct for the nuances of feminine eroticism, Klimt registered the actions and reactions of women who gave themselves over to this intimate activity before his eyes uninhibitedly (Klimt’s charismatic hold over his models was legendary).

Lesbianism and pregnancy were also depicted by this resolute explorer of “the theme ‘woman.'” As Tobias G. Nater says in his catalog essay on Klimt’s illustrations of an unabridged German translation of Lucian of Samosata’s Dialohe Hetaerae (1905):

Klimt’s drawings made an abundant contribution to the iconography of the forbidden…. Klimt depicted women in onanistic raptures, illustrated the erotic potentials of self-contemplation, and took on the voluptuous theme of lesbianism. In doing so, he managed both to touch on age-old prohibitions and to engage (primarily) male fantasies.

Many of the drawings, it should be said, are beautiful as well as shameless. They are bigger, with a calmer line, than those of Klimt’s younger contemporary and fellow explorer Egon Schiele. As Nater points out,

Schiele, working at the borderlines between Jugenstil and Expressionism, had a very different, basically self-referential (even self-destructive) approach to his depictions. Klimt, by contrast, was a draftsman in the purest sense.

However hastily scribbled his sketches are, his academically trained conscience does not permit him Schiele’s anatomical distortions, or the undercurrent of desperate unhealth emphasized by Schiele’s splotches of color. Klimt’s hetaerae are healthy, though they doze a lot.

Together, the two men restored genitals to the nonpornographic nude, and sketched sex in something like its melancholy complexity. Vienna in the first decades of the twentieth century was the capital of sexual realism, as Freud, paper by paper, carefully placed the sex drive at the center of the human psyche. Klimt, with his harem of languid models and society portrait subjects (portrait commissions, almost always of women, were his financial mainstay), did his part, and his drawings of nudes broke ground; but drawings are not enough to generate revolution in art, and his ambition was nothing less. The first president of the Viennese Secession, he followed as well as initiated artistic currents. Among the foreign influences to which he exposed himself was that of the art newly imported from Africa. In 1914, his catalog biography notes, “he visits the Brussels Musée du Congo, and is deeply impressed by the sculptures displayed.” Maybe so, but it was Picasso’s impulsive inclusion of African heads in the discordant, unfinished Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) that marks, in most art histories, the beginning of the modern. Picasso, with Cubism and his subsequent radical distortions of human form, dug below the skin of reality; Klimt stayed on the surface with his appliqués of abstract pattern, his gaudy faux fabrics.

Klimt’s awkward position on the threshold of modernism suggests that of James McNeill Whistler, whom Klimt admired and imitated. Both men heard modernism’s call to “make it new,” but didn’t know quite how to answer. As Manu von Miller says in her catalog essay “Embracing Modernism: Gustav Klimt and Sonia Knips,”

Klimt shared with Whistler a penchant for elaborate and effective systems of decoration…. They both had an abiding interest in Far Eastern arts, and were drawn toward creating a break from representational depiction and planar pictorial conventions…. Klimt’s “white women portraits”—Serena Lederer (1899), Gertha Felsövanyi (1902), and Hermine Gallia (1903–04)—recall Whistler’s depictions of girls dressed in white and surrounded by flowers, known as his Symphonies in White (painted between 1862 and 1873).

Both men, he might have said, were combative poseurs, who put into their flamboyant bachelor lives the artistic energy that, toward the end, leaked away in a litter of uncompleted canvases.

As far as paintings at the Neue Galerie go, there are not enough—eight, all told; Hope II (Vision) (1907–1908), a pregnant woman in profile between two slabs of flecked gold, hangs on the third floor in a reconstruction of one of Klimt’s studios—to show the curve of a career. Most of his best pre–Golden Style paintings, such as the luminously tense and feathery portrait of Sonja Knips (1898), are still in Vienna; some, like Schubert at the Piano (1898–1899) were destroyed or lost during the war. The Neue Galerie owns two large-scale portraits and two interesting studies of female heads, but none of the lush aquatic fantasies—Moving Water (1898); Nixies (Silver Fish) (circa 1899); Goldfish (1901–1902); Water Serpents I and II (both 1904–1907)—whereby Klimt illustrated his scandalous enthusiasm for Darwin’s theory of evolution.

His controversial murals defy importation, but a large three-part reproduction of his casein-on-stucco Beethoven Frieze (1902) more than satisfies our appetite for Art Nouveau symbolification. The main panel contains three nude gorgons (Sickness, Mania, and Death), three personified sins (Licentiousness, Intemperance, and Indecency), a cartoon gorilla representing the ancient Greek evil giant Typhon, a human male and female embracing within a transparent amniotic sack, an octopus, and semi-abstract forms that represent primitive organisms and/or evolving geometric order. All this, and allusions to Goethe, too.

The Neue Galerie was founded, on the strength of one man’s passion and fortune, to give a presence, along Manhattan’s Museum Row, to German and Austrian art, particularly that of the early twentieth century. The newly acquired Klimt, notorious for its purchase price, makes, with its attendant exhibition, the requisite stir, and impressively sustains the mission.

This Issue

December 20, 2007