1.

Despite the inherently social nature of architecture and city planning, personal histories of master builders were uncommon before the last century, and are still greatly outnumbered by biographies of painters and sculptors. A turning point in the public’s perception of the building art came with the publication of Frank Lloyd Wright’s An Autobiography of 1932, a picaresque narrative that captivated many who hadn’t the slightest inkling of what architects actually did. Wright’s self-portrait as a heroic individualist served as the prototype for Howard Roark, the architect-protagonist of Ayn Rand’s 1943 best-seller, The Fountainhead. But the novelist transmogrified Wright’s entertaining egotism into Roark’s suffocating megalomania, an image closer to that of another contemporary coprofessional: Le Corbusier, the pseudonymous Swiss-French architect and urbanist born Charles-Édouard Jeanneret in 1887, twenty years after Wright.

Le Corbusier was the only one of Wright’s competitors who matched his flair for self-promotion. However, Le Corbusier’s posthumous influence has outstripped that of the greatest American architect. His schemes were often less specific to their sites than Wright’s, and thus more adaptable elsewhere. Le Corbusier’s work in South America and India won him a third-world following Wright never attracted. And his “Five Points of a New Architecture” of 1926 became a modern “must” list that could be copied by almost anyone, anywhere. It included thin piloti columns on which buildings could be based; ribbon windows; open floor plans; façades freed from load-bearing structure; and roof gardens. Such formularization was also central to the steel-skeleton, glass-skin high-rise format later perfected by a third contemporary, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, but it did not offer the recombinations possible with the “Five Points.”

During Le Corbusier’s lifetime, his reputation did not derive solely from his vast corpus of designs, which still astonishes in its inventiveness and boundless implications. His renown was enormously enhanced by the more than fifty books and pamphlets through which he promulgated his radical vision of a new building art for the modern age—everything from city planning to interior design. For example, to replace the tightly knit, medium-rise urban neighborhoods Le Corbusier deemed insalubrious and oppressive, he proposed residential skyscrapers widely spaced amid parks and highways. To modernize domestic interiors cluttered with ornate furnishings and cocooned in fabric, he advocated rooms as sparse and easy to clean as a tuberculosis ward. And rather than reiterating the dull gray masonry of northern European cityscapes, he favored the gleaming white stucco of Mediterranean villages, regardless of climatic suitability.

Le Corbusier was electrified by the feedback he got when he expounded his controversial proposals in public, whether to lay audiences or fellow practitioners. His need for attention (the source of which is finally established in the first full-length Le Corbusier biography, by Nicholas Fox Weber) was fed by the heavy schedule of speaking engagements he kept up for decades. This important aspect of the architect’s program is analyzed in depth in The Rhetoric of Modernism: Le Corbusier as Lecturer by Tim Benton, the foremost authority on the man he has termed “the architect of the century.”

With customary thoroughness and cogency, Benton presents yet another fascinating facet of an oeuvre that, like Picasso’s, yields more and more the deeper scholars delve into it. Le Corbusier attended many of the symposia convened by supporters of modern architecture to hash out their theories and establish a unified agenda. Those meetings could be contentious, for what we now call “the Modern Movement” was in fact an unruly scrum of competing factions with doctrinaire positions that often divided an allegedly common cause.

Most architects give lectures primarily to advertise themselves, and Le Corbusier was no less shy than his colleagues in basing his talks on his own work. What set his appearances apart was the way they prompted him to reexamine fundamental concepts—from the organization of metropolitan transport to the layout of the workingman’s house—as much for himself as for his listeners. Whatever his announced topic, he emphasized a constant theme: his version of modernism held unique promise for elevating mankind to unprecedented levels of bodily well-being and psychic stimulation.

Despite Le Corbusier’s interest in theory, his discourses were anything but cerebral abstractions, and conveyed a vigorous physicality thanks to the method through which he illustrated his thoughts. His visual aids were low-tech yet high-impact. On the wall behind him, the architect would unroll and pin up a swath of yellow tracing paper as wide as a movie screen. While he spoke, he used varicolored chalks or crayons and sketched a profusion of pictograms, scrawled a welter of catchphrases, and ended up with a dense calligraphic mural like a Cy Twombly drawing avant la lettre. Many such Corbusier lecture backdrops survive, intact or in tatters, thanks to souvenir hunters who swooped in and claimed them the second he exited the stage.

Advertisement

The prolific Benton has also revised and enlarged his definitive 1984 monograph on the houses of the architect’s so-called Heroic Period. The title of this new version, The Villas of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, 1920–1930, has been expanded from that of the first edition to duly credit Pierre Jeanneret, the master’s cousin and collaborator on the nineteen schemes (fifteen of them executed) for sites in or near Paris. When they were new, these starkly unornamented, defiantly uningratiating structures reminded many of factories. Le Corbusier took the analogy as a compliment and duly dubbed his new domestic conception the machine à habiter—“machine for living in.” Today, these houses accord with popular notions of Bauhaus architecture, even though Le Corbusier had no official connection to that German design school.

In tracing the evolution of the Heroic Period houses, Benton shows how the designers extracted a remarkable array of compositional variations from a narrow repertoire of forms—right-angled volumes, flat roofs, windows flush with wall planes—and a limited palette of materials—white-painted stucco, glass, and metal. Le Corbusier and Jeanneret were able to do so much with so little mainly because of the former’s genius for reconceiving space in novel ways, a gift he came into full possession of during this determinative decade.

The climax of the cousins’ astonishing residential sequence was the Villa Savoye of 1928–1929 in Poissy, in my estimation (and that of many others) the ultimate twentieth-century house (see illustration on page 34). Its vivifying counterpoint of geometric rigor (through the ancient proportional system known as the Golden Section) and spatial propulsion (through dynamic ramps in place of stairs) makes the structure exhilarating to move through every step of the way from front door to roof terrace. By the time this job was finished, the architects likely realized that they had pretty much exhausted their formula and could only repeat themselves if they stuck with it.

Le Corbusier soon began to move away from industrial perfectionism and toward its polar opposite in a nascent neoprimitive style, which emerged with his introduction of rough stone walls in several country houses of the 1930s, and culminated with his gloriously anti- rational Ronchamp chapel in France two decades afterward. However, though he abandoned the mechanistic approach of his Heroic Period, the Corbusian vocabulary would become so pervasive that its author’s main contribution might be seen as his codification of the closest to a true lingua franca that ever emerged from the babel we call modern architecture.

2.

It was one thing for Pierre Jeanneret to collaborate with Le Corbusier, but quite another for Le Corbusier to collaborate with the Nazis. Years before France fell in 1940, Hitler’s hatred of modern architecture had spurred a steady emigration of practitioners whose careers in Germany had collapsed. Albert Speer, Hitler’s principal architect, urban planner, and wartime munitions chief, visited Paris to oversee his country’s pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair. After the war he acknowledged being familiar with Le Corbusier’s work, which perhaps informed his megalomaniacal plans to rebuild Berlin on a scale Le Corbusier had envisioned for Paris. But Speer’s Stripped Classicism and Le Corbusier’s minimalist Modernism were too disparate in essence for any middle ground.

Le Corbusier, oblivious (for once) to his international identity as vociferous champion of the very architecture Hitler despised, somehow imagined he could find a position with Marshal Pétain’s government. He moved to the provisional capital of Vichy, where he assiduously but fruitlessly lobbied for work. He was fortunate to have failed, which made it that much easier to hide this shameful episode after the Liberation, when he reopened his office in Paris as though the preceding four years had never happened.

During the second half of Le Corbusier’s career, following World War II, he designed many fewer single-family houses than before. Most important among his later private domestic commissions were the Maisons Jaoul of 1951–1955 in the Paris suburb of Neuilly. That pair of smallish villas, commissioned by a father and son, is the subject of a new monograph by Caroline Maniaque Benton, who is married to Tim Benton and here provides a worthy pendant to her husband’s likewise indispensable study of the Heroic Period houses.

The Maisons Jaoul are stylistically antithetical to the Le Corbusier– Jeanneret residences. Whereas the sleek Villa Savoye, with its main living areas lofted above the terrain on slender pilotis, seems barely tethered to its site, the compacted brick-and-concrete Jaoul houses feel immovably earthbound. The Savoye house, with its peripheral colonnade supporting an entablature-like piano nobile, encouraged comparisons to the Classical tradition; the fortresslike enclosure and monastic gravity of the Maisons Jaoul provoked references to the Medieval.

Advertisement

The Neuilly double houses quickly became touchstones of New Brutalism, a trend among young architects in mid-century Britain. They sought to inject much-needed energy into the waning conventions of High Modernism, as represented by carbon-copy commercial hackwork that sucked the marrow out of Mies’s “skin-and-bones” formula. The New Brutalists saw greater expressive potential in Le Corbusier’s favorite late-career material, concrete, though the effortful crudeness of their chunky forms and rough finishes often seemed little more than macho posturing. Paradoxically, although their hero Le Corbusier built nothing in Britain, he became the presiding spirit among Modernist architects there, especially during the massive postwar reconstruction, exemplified by Hubert Bennett and Jack Whittle’s Hayward Gallery of 1964–1968 on London’s South Bank, an inert concrete blockhouse.

Polarization of critical opinion on this divisive figure is instructively represented in Le Corbusier and Britain: An Anthology, a collection of more than fifty texts assembled by Irena Murray and Julian Osley (respectively, the director of, and a librarian at, London’s Royal Institute of British Architects library). The editors bring together several classic postwar essays—including the historian Colin Rowe’s “The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa: Palladio and Le Corbusier Compared” and the architect James Stirling’s “Garches to Jaoul: Le Corbusier as Domestic Architect in 1927 and 1953″—as well as obscure but impressive writings from the interwar period. Among the latter are Le Corbusier’s impassioned if impressionistic panegyric on Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace of 1850–1851 in London (written a few days after that founding landmark of Modernism was destroyed by fire, in 1936) and the great Classicist Edwin Lutyens’s cautiously appreciative 1928 review of Towards a New Architecture (the English translation of Le Corbusier’s most seminal text, Vers une architecture of 1923).

Lutyens, who resurrected Classicism more convincingly than any other architect since John Soane, knew what he was talking about when he proffered Le Corbusier this collegial admonition:

Architecture, certainly, must have constituents, but lines and diagrams, in two dimensions, are not enough. Architecture is a three-dimensional art. To be a home, the house cannot be a machine. It must be passive, not active, bringing peace to the fluctuation of the human mind from generation to generation. For what charm can a house possess that can never bear a worn threshold, the charred hearth, and the rubbed corner?

The fiercely competitive Le Corbusier was unusually respectful of Lutyens’s consummate triumph—the Viceroy’s House of 1913–1931 in New Delhi—when he visited it in 1951 as he began planning Chandigarh, his new regional capital of 1951–1964 for the Punjab—and he adopted several of the Englishman’s ideas for that evolving scheme. Indeed, Le Corbusier’s eventual volte-face from the machine à habiter of his Heroic Period to the archetypal foyer de famille of his Maisons Jaoul suggests that he took Lutyens’s 1928 critique very much to heart.

Le Corbusier had a size fetish, and made headlines during his 1935 trip to America when he complained that New York’s skyscrapers were too small. He’d adore Le Corbusier Le Grand, a twenty-pound folio-sized tome. When this behemoth is freed from its slipcase and opened, it brings to mind a sports-stadium Jumbotron. The introduction, by the architectural historian Jean-Louis Cohen, and the chapter introductions, by Tim Benton, are lightweight by their high standards, but magisterial in contrast to the book’s shockingly error-riddled picture captions (the unsigned work of other contributors).

Another recent book proves that exciting visual treatment of this subject does not depend on inflated dimensions. The sensibly sized Le Corbusier: The Art of Architecture accompanies an excellent exhibition now in London, concluding its two-year European tour. This catalog contains some fine essays, especially those by the show’s organizers—the Swiss architectural historians Stanislaus von Moos and Arthur Rüegg—and Cohen, whose “Sublime, Inevitably Sublime: The Appropriation of Technical Objects” investigates Le Corbusier’s fascination with modern ocean liners and its effect on his conception of large-scale residential schemes, specifically the six Unité d’habitation apartment developments he built in France and West Berlin during his two final decades.

The most bizarre and inexplicable book on this (or any other) architect to appear lately is Le Corbusier and the Occult by J.K. Birksted, who teaches at the Bartlett School of Architecture at University College London. The author maintains that his subject was profoundly affected by Freemasonry, an insight that had eluded scholars for the simple reason that Le Corbusier never joined the Loge L’Amitié—the Masonic chapter in his Swiss hometown of La Chaux-de-Fonds. Undeterred, Birksted insists that the architect was much influenced by several loge illuminati, whom he knew from the hiking group headed by his father, Georges-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris.

Birksted sees validation of his thesis in Le Corbusier’s buildings, early and late. He discerns the hallmark Masonic pyramid motif atop the architect’s Villa Jeanneret-Perret of 1912 in La Chaux-de-Fonds (a house that nearly bankrupted his parents), although the roof is neither purely pyramidal nor a configuration alien to Alpine regions. Le Corbusier discussed everything of any significance to him in his copious and confessional correspondence, and his silence therein about Freemasonry consigns Birksted’s fanciful theory to the realm of baseless speculation.

3.

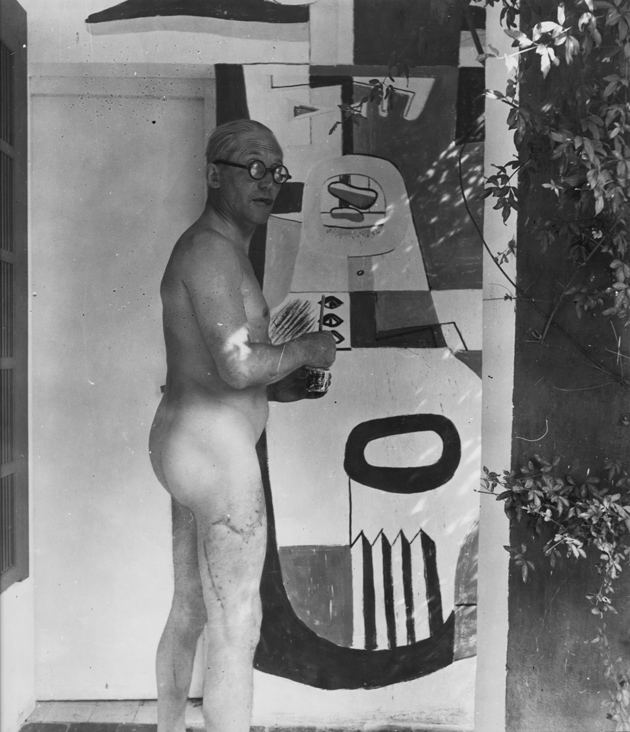

Although Le Corbusier was determined to be well-known, he was also determined not to be known well. He never added an autobiographical memoir to his extensive writings, and he disclosed so few personal details that he seemed to have no private life at all. However, one thing everyone knew about him was his relentless Protestant work ethic, befitting the son of a Calvinist watchmaker. But as Nicholas Fox Weber persuasively argues in his revelatory and absorbing Le Corbusier: A Life, the architect was driven by motivations more primal than compulsive Swiss industriousness.

Weber gets to the heart of the matter by employing Le Corbusier’s own words to document his ceaseless struggle to win the love and affirmation of his mother, Marie Charlotte Amélie Jeanneret, née Perret (no relation to the Belgian-born architects Auguste and Gustave Perret, with whom Le Corbusier apprenticed). Mme Jeanneret, a music teacher, openly preferred her older son, Albert, a musician of middling talent and feckless temperament. Parental approval is seldom swayed by adult achievements of less-favored offspring, and nothing Le Corbusier ever did could alter that family dynamic.

This previously unknown factor in the architect’s psychic makeup is a discovery of immense importance, and Weber is right to give it a prominent place in his well-paced and judiciously balanced narrative. He is also correct to avoid simplistic psychological diagnoses, and lets the primary evidence speak for itself. The results are so convincing that, even without knowing the full contents of the architect’s archive, it seems safe to say that Weber has done an extraordinary job of surveying the long-sequestered papers and has charted a plausible map of the inner man.

Weber, the author of numerous books on art, was the first writer granted unrestricted access to Le Corbusier’s private correspondence, preserved at the Paris foundation he created to guard his legacy. The architect’s executors, who fended off prospective biographers for more than three decades, were wise to choose Weber. Though not a trained architectural historian, he unquestionably likes his subject, and remains unwaveringly sympathetic, often in the face of quite unpleasant evidence. Yet he also indicates why the Fondation Le Corbusier delayed a full biographical accounting for such a scandalously long time.

The architect constructed a public persona of hyperrational control and glacial indifference, which some have seen reflected in the inhumane streak suggested by his drastic urban renewal schemes (most notoriously his Plan Voisin of 1925, which would have razed much of Paris’s Right Bank) and unreciprocated Nazi sympathies. But the infantile tone of his letters to his mother—by turns fawning, petulant, wheedling, flirtatious, obsequious, demanding, hectoring, and every bit as selfish and manipulative as the ghastly matriarch herself—exposes his appalling lack of empathy for anyone but himself and the mother from whom he could never separate.

Weber goes so far as to assert that Le Corbusier’s most acclaimed postwar work—the pilgrimage church of Notre-Dame-du-Haut of 1950–1955 in Ronchamp, France—was less a shrine to Our Lady than his utmost tribute to his maman, also named Marie. Without question, the cavernous biomorphic interiors of this miraculous structure (reckoned the most moving religious building of modern times by many critics, including this one) do indeed echo the sensuous contours of the female anatomy. The words from the Hail Mary that the architect inscribed, in his own hand, on one of the chapel’s jewel-like stained glass windows—bénie entre toutes les femmes (“blessed among all women”)—hint at a devotion beyond any this nonobservant Protestant ever evinced for organized religion, let alone the Blessed Virgin. Even so, it would be a mistake to see Le Corbusier’s transcendent hilltop sanctuary as a womb with a view.

Despite Weber’s fondness for his subject, he unsparingly condemns Le Corbusier’s despicable attempts to abet the Vichy regime. The architect’s chilling remarks disclose attitudes deeper and more disturbing than mere vocational opportunism. Five months into the Occupation, he reported to his mother in neutral Switzerland:

The Jews are going through a very bad time. I am sometimes contrite about it. But it does seem as if their blind thirst for money had corrupted the country.

He was willing to work for anyone—but so was Mies, and many other architects throughout history. However, in this as all else, everything was always about him. Le Corbusier saw wartime destruction not as a human tragedy but as a career opportunity. “There are great demolitions only when a great building site is about to open,” he wrote his mother. And with grotesque effrontery, this expedient Pétainiste postured as if he’d taken up arms with the Maquis: “I will not and cannot leave France after this defeat,” he declared. “I must fight here where I believe it is necessary to put the world of construction on the right track.”

4.

Apart from Le Corbusier’s manie de maman, his most consuming personal relationship was with his wife, Yvonne Gallis. Their three-decade mésalliance was so complex and dispiriting that Weber is understandably baffled by its precise pathologies. One only hopes the sex was good, at least for her. (For his part, the architect was always happy to outsource with independent contractors.) At first glance, this unlikely pairing of a Swiss-French control freak and a Monégasque free spirit appears the proverbial attraction of opposites. However, Le Corbusier was habitually drawn to two very different sorts of women.

One was the self-assured, well- educated young lady of good breeding and independent means—epitomized by the American divorcée Marguerite Tjader Harris, with whom he conducted a fitful three-decade extramarital affair, until he summarily dumped her in the early 1960s, when a commission she tried to broker on his behalf fell through. The other feminine archetype that most aroused him was the Mediterranean peasant girl—intuitive, uninhibited, sensuous, and pleasure-loving—personified by Yvonne. As Le Corbusier wrote in his La Ville radieuse of 1935:

I am attracted to a natural order of things…. And I have noticed that in my flight from city living I wind up in places where society is in the process of organization. I look for primitive man, not for their barbarity but for their wisdom.

In 1929, seven years after he took up with Yvonne and a year before they married, Le Corbusier had a brief but intense romance with Josephine Baker, the African-American chanteuse-vedette, whom he met (along with her complaisant husband) on a trip to Buenos Aires. Superficially, these two international stars might be one of Miguel Covarrubias’s Vanity Fair “Impossible Interviews” (caricatures that coupled Sigmund Freud with Mae West, and Greta Garbo with Calvin Coolidge). But the lovers regarded each other as kindred spirits of childlike simplicity. The architect also saw a potential client, though talk of his designing an orphanage for La Baker in the south of France came to naught.

Without assigning blame, Weber follows Yvonne’s steady, seemingly inexorable disintegration, physical and spiritual—through alcoholism, eating disorders, wartime malnutrition, her husband’s protracted absences, and his emotional neglect—in harrowing detail made more pitiable in contrast to the vivacious young minx she was when Le Corbusier first fell for her. Yvonne had been a mannequin in Monte Carlo, and like many fashion models her soignée looks were belied by her common behavior. She adored juvenile pranks, bawdy repartee, popular amusements, and anything that tweaked bourgeois proprieties. So did her husband, his cool public pose notwithstanding.

Le Corbusier ate up the naughty provocations of his “Vonvon,” which further encouraged her. (She called him “Doudou,” a diminutive of Édouard, as well as baby talk for merde ). At architectural conferences as well as private soirées, she became his surrogate id, blurting out home truths her careerist spouse considered too impolitic to voice personally. Weber recounts a memorable evening chez Corbu when Walter Gropius (then director of the Bauhaus) and his new wife, Ise (successor to the celebrated Alma Mahler), came to dine. Yvonne, bored silly by the stuffy couple, suddenly asked Gropius if he’d seen it. When he inquired what “it” meant, she slapped her rump and brightly exclaimed, ” Mon cul! ”

Reports of Mme Le Corbu-sier’s blistering candor circulated in professional circles for decades. She was as blunt with her husband as with everyone else, which seems not to have bothered him. Decades before the new biography, a rare, evocative personal study of the pair—albeit in miniature—appeared in Charles Jencks’s Le Corbusier and the Tragic View of Architecture of 1973, which Weber’s exhaustive research shows to have been a small masterpiece of induction. Jencks cites Yvonne’s reaction to the glass-walled duplex Le Corbusier created for them atop his small sixteenth-arrondissement apartment house of 1933, the new home he hoped would give them “a new life”:

“All this light is killing me, driving me crazy,” she said…. [Le Corbusier] placed a bidet, that beautifully sculptural “object-type,” right next to their bed. She covered it with a tea cosy.

The architect treated Yvonne appallingly all along, but it is not surprising to learn that her death, in 1957, left him desolate for the eight years that remained to him. The bereft widower made a macabre talisman of one of Vonvon’s vertebrae, which survived her cremation intact. Something essential went out of Le Corbusier in that final phase, when he seemed to withdraw from the world, creatively and personally.

The architect’s sudden death, in 1965, from an apparent heart attack as he swam in the Mediterranean against cardiologist’s orders, led some to wonder if it was a suicide—the architectural equivalent of Joan Crawford striding into the surf to the strains of the Liebestod at the climax of Jean Negulesco’s Humoresque of 1946. Le Corbusier’s implacable mother had died in 1960, just months before her centenary, and he always believed he would live as long as she. Whether his own demise, at seventy-seven, was accidental, intentional, or something in between, the departure of the two women he could neither live with nor live without had left him very much at sea well before the waves closed over him.

This Issue

April 30, 2009