Michelle Obama’s kitchen garden on the South Lawn of the White House merits a double brava!—apart from calling attention to the nutritional value of eating fresh, organically grown vegetables, it honors their global origins. We are not only a nation of immigrant peoples and cuisines. We are also a country of immigrant plants, trees, and vines. Mrs. Obama’s garden inevitably, if not intentionally, expresses that diversity, with its radishes, rhubarb, and spinach from Asia, its kale, broccoli, lettuce, and oregano from the Mediterranean, its fennel from India and Egypt, and its border marigolds from Mexico.

When European settlers first arrived in North America, they found an abundant garden. Blackberries, raspberries, and blueberries, which are planted about eight feet north of the White House vegetable patch, grew prolifically in the woods. The Indians gathered them from the wild, but they also cultivated corn and sweet potatoes, which had come from Latin America, as well as squash and beans, which they had bred from indigenous plants.

Plant improvement can result from advantageous mutations. It can also arise from sexual crossing, whereby the pollen from the stamens (the male sexual organ) in one plant penetrate the pistil (the female organ) in another, fertilizing it. Such crossing occurs all the time in nature, the pollen being carried by wind, insects, and birds. Like plant breeders since ancient times, the Indians improved their crops by selecting for reproduction the superior progeny produced by mutation or by natural pollination either within one plant variety or between two different varieties planted in proximity to each other. They were ignorant of the mechanism of sexual crossing, believing in cases of mixed varieties that the two somehow mingled their characters through the entanglements of their root systems.

No matter their misunderstanding: their breeding practices were effective. They planted the superior seed, selected superior plants from the next crop, and obtained improved varieties by repeating the process through successive generations. They introduced these varieties to the European newcomers, who were very glad to have them. In 1923, Lyman Carrier, an expert on the origins of American agriculture, noted that “no people anywhere in the world ever made greater strides in plant breeding than did the American Indians,” adding, “Our agriculture is at least one-third native American.”1

However, most of the rest, like almost all the plants in the White House garden, have come from elsewhere on the planet. From the first Spanish arrivals, European conquerors and settlers supplemented the native fruits and edible plants with basic food from the Old World and the southern half of the new one, including wheat, rye, barley, and oats; lettuce, onions, cabbage, and asparagus; eggplant, cucumber, okra, and beets; carrots and cauliflower; celery and parsley; parsnips, peas, and turnips. They also imported pasturage grasses, such as alfalfa, clover, timothy, and bluegrass, to feed their livestock, a type of husbandry that the Indians did not practice.

The colonists took a special interest in fruits, steadily supplementing the bitter-tasting wild crabapple and the few native varieties of plums with fruits from Europe, notably apple, pear, peach, and cherry trees. Farms commonly had an apple orchard, its produce pleasing to the palate and a convenient source of nourishment and sweetening that was preservable for many months in the form of cider. Grown from seeds and seedlings, a few trees yielded, by means of chance cross-pollinations by insects and other agents, particularly tasty fruits—for instance, the Jonathan apple, which was found on a farm in Kingston, New York, and made known by Jonathan Hasbrouck to a local judge, who returned the favor by naming the apple for him.2

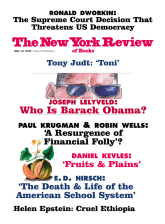

Yet during the first years of the republic, the United States remained a colonial dependency, importing quality fruits, a condition that, as Philip Pauly reveals in his eye-opening Fruits and Plains, helped give rise to a drive for horticultural improvement that persisted into the twentieth century. It helped transform the nation as it stretched across the continent, contributing to the gorgeous abundance that the poet Katharine Lee Bates celebrated in “America the Beautiful,” the homage to which Pauly’s title alludes. Pauly, who died of cancer at the age of fifty-seven in 2008, was a prominent historian who studied the development of biology in the perspective of American culture and politics.

Like his previous works, Fruits and Plains is skilled, authoritative, insightful, and original, a pioneering exploration of innovation in American horticulture and its relationship to the natural environment during the two centuries or so that preceded the recent emergence of agricultural biotechnology. It merits a prime place in the growing historical literature concerning the linked subjects of agricultural development, agribusiness, the environment, biological science, food, and globalization. It is a particularly valuable complement to the recent study by the economic historians Alan L. Olmstead and Paul W. Rhode, Creating Abundance, which convincingly argues that since the early nineteenth century biological innovation has been as important as mechanical invention in dramatically increasing the productivity and variety of American agriculture.3

Advertisement

Pauly brings to life a remarkable cast of characters—in the main gentlemanly and middle-class amateurs, commercial nurserymen, scientists, and government officials. Some, like Thomas Jefferson and Frederick Law Olmsted, are familiar figures, but most, like the Boston plant breeder and nurseryman Charles M. Hovey or the crusading entomologist Charles Marlatt, are not. They were a knowledgeable, hard-headed, and practical lot, in many ways visionary, passionate about trees as such, as well as fruits, and concerned with lawn, pasture, and range grasses. Pauly relegates to “populist folklore” the importance of untutored plantsmen such as John Chapman or Luther Burbank, calling celebrations of them “seriously misleading,” in view of the skills required for the development of American horticulture.

He is right about Chapman, whose elevation to mythic hero as Johnny Appleseed may be merited by the mystic and selfless nature of his character but not by the consequence of his plantings. Apple trees grown from seed yield qualitatively poor fruit, usually good for cider but not for eating, while trees grown from cuttings of trees bearing quality fruit will produce fruit of comparable merit. But he is too hard on Burbank, whose plant-breeding methods were mysterious but who devised a number of delectable new fruits—for example, the Golden Plum, the Flaming Gold Nectarine, the Black Giant Cherry—and was a successful businessman.4

The drive for horticultural improvement was of course associated with an eagerness to promote economic development. At the outset, horticulture was centered in the northeastern United States, where new lands for cultivation were in short supply and those that were under cultivation were suffering increasing soil depletion. Crop rotation and manure were widely touted as the remedy for the latter, but a strategy of using more productive and higher-quality fruits (as well as animals and other plants) was advanced as a means to use the land more efficiently.5 The improvers were also driven by national pride. Their dependency on foreign fruits rankled, and so did claims by European scientists that plants and animals degenerated in the American environment.

A major element in the strategy of improvement was to find and develop valuable indigenous plants. Among the first successes was Hovey’s Seedling Strawberry, a newcomer for the garden that Charles Hovey, soon America’s leading horticulturist, bred in the mid-1830s. The woods contained tasty wild strawberries, but they were difficult to grow in gardens, and luscious imports from England did not survive the northeastern winters. Hovey developed his strawberry by successively crossing several different varieties—fertilizing one variety with the pollen of another—then planting seed from promising plants. His Seedling Strawberry, which he plucked from the ultimate crop, produced large fruits with shining red flesh and delicious juice.

Pauly points out that horticulture, including plant improvement in the pre-Mendelian nineteenth century, was an important element in the history of American science, though it has largely been unrecognized as such because it was to a great extent “an art…not a science on the academic model.” Hovey’s Seedling Strawberry provides a case in point. The first purchasers of his vines found that they tended to produce few if any fruit. An explanation came from Nicholas Longworth, a lawyer who had accumulated a fortune in real estate in Cincinnati, Ohio, and, like a number of newly rich Americans in the Northeast, had turned to horticulture. Strawberries, he argued, were sexual plants—some male, others female. Hovey’s Seedling Strawberry was female. It would fruit only if it were grown together with a male variety whose pollen would fertilize it.

The issue of whether strawberry plants are sexually distinct had been an undercurrent in European botany for at least a century. Now Longworth’s claim precipitated a debate over what Pauly calls “the great strawberry question” that persisted among American horticulturists for some twenty years until it was eventually resolved in Longworth’s favor. (Longworth went on to greater triumphs, producing the first widely appealing wine—Catawba sparkling wine—made from a native grape and a great-grandson who would become speaker of the House of Representatives and marry Theodore Roosevelt’s daughter Alice.)

Pauly notes that American fruit breeders also debated which of two methods to employ for horticultural improvement. One, advanced by the English horticulturist Thomas Andrew Knight, called for hybridization across different varieties. The other, championed by the Belgian pear breeder J.B. Van Mons, stressed the repeated selection of seeds from specimens of the same variety that grew weakly but that produced soft-skinned and meltingly tasty fruit. Hybridization, however, was a laborious process, and in the mid-nineteenth century American horticulturists seemed, like the Indians, to rely on seed selection from promising varieties that were often the product of natural hybridization by birds and bees.

Advertisement

Ephraim Bull, a nurseryman in Concord, Massachusetts, produced the Concord grape by planting the seeds of a “volunteer”—a plant grown from a seed that had fallen naturally to the ground and germinated—that he found in the corner of his garden. Then after it fruited, in 1843—Bull guessed, plausibly, that the fruit resulted from fertilization by a Catawba grape—he planted the seeds from the fruit and used Van Mons’s rules to select the resulting vines for propagation. Bull’s new variety ripened two weeks earlier than the earliest grape then known and yielded large clusters of delicious fruit, good for the table and for wine. It created a sensation in the horticultural world after it was first exhibited at the Massachusetts Horticultural Society in 1853.

Pauly stresses that for all the success of Hovey or Bull, one of the horticultural improvers’ principal strategies for eventually achieving American independence from Europe in fruit growing was continued importation and naturalization of promising new species to the American environment. Attempts to develop new fruit trees and vines were beyond the resources of all but a few horticulturists, and the process was risky. (Hovey estimated that “the chance of raising a very superior fruit may be considered as one to five hundred.”6🙂 Like English strawberry plants, arrivals from abroad often failed. New York, for example, might be on the same latitude as Rome, but imported fruit trees and vines fell victim to American soils, insects, and climates, including late spring and early autumn frosts as well as the torrid heat of summer. Thomas Jefferson attempted to develop orchards of diverse fruits, including especially European wine grapes, at Monticello and nearby Colle, thinking that the region resembled a fruit-rich area of Italy, but early spring frost did in most of the trees and the grapevines tended to die after two or three years.

Plant importations were the product of both private and public efforts. Jefferson remained an avid importer, writing in 1800: “The greatest service which can be rendered any country is to add an [sic] useful plant to its culture.” In Massachusetts, well-to-do amateurs obtained fruit trees and vines from nurseries and fanciers in England and France, and cultivated them in their orchards and estates. The private improvers pursued horticulture in a spirit of noblesse oblige, circulating buds and scions for propagation by gift and exchange. (Neither plants nor animals could be patented at the time.7🙂

In 1829, they founded the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, modeled on its counterpart in London, which promoted its purposes in the region by offering prizes for fine fruits displayed at its exhibits and afterward toasting the glories of horticulture in lengthy and bibulous banquets. By the mid-nineteenth century, however, the task of private importation was falling increasingly to commercial nurserymen, members of a rapidly growing industry, who bought seeds, cuttings, and plants by the hundreds from their counterparts in Europe and, as Pauly observes, sold what they imported throughout the country.

The first significant federal effort to import plants originated in the late 1830s in the Patent Office at the initiative of Henry Ellsworth, a son of the second chief justice of the United States. He persuaded Congress to establish an agricultural division in the office (it evolved by 1862 into the Department of Agriculture, or the USDA) and authorized it to seek new plants from abroad. The Patent Office was of course devoted to securing monopoly rights for inventors. Pauly notes that Ellsworth made its activities more palatable to Jacksonian opponents of monopoly, providing imported plants and seeds to members of Congress for testing by distribution to their constituents.

Federal plant importation as well as seed distribution, both located in the Department of Agriculture after 1862, had their ups and downs through the rest of the nineteenth century. Importation thrived when the United States, having acquired western lands from Mexico, sought plants that would do well in an arid environment. Seed distribution lagged when Cleveland Democrats waged war against government extravagances. Along the way, the Department of Agriculture established an experimental garden with greenhouses on the eastern end of the Mall, where it tested imported plants.

Following the Republican victory in 1896 and the Spanish-American War two years later, the government—in keeping with the country’s drive for new markets, new territories, and new resources—embarked on a long-term program to acquire economically advantageous new plants. The prime mover in this agricultural expansiveness was Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson, a successful Iowa politico and, with Henry Wallace, whose son and grandson would also serve in the office, an advocate of agricultural science and modernization. He established a systematic program to seek out plants and seeds from around the world and to test and distribute them in the United States.

The program was headed by David Fairchild, the son of a Kansas abolitionist and president of the state agriculture college. During the 1890s, Fairchild was taken under the wing of Barbour Lathrop, then forty-five, “who had,” Pauly writes, “diffuse interests in agriculture and well-formed young men.” With the vague aim of searching for new plants, Lathrop took him on a tour of the Pacific region in 1896 and of South America in 1899. Fairchild’s friendship with Lathrop transformed him “into a self-confident cosmopolitan,” Pauly notes, and his marriage in 1905 to one of Alexander Graham Bell’s daughters provided him with cachet and connections that served him well in Washington’s agricultural politics.

In 1909, Fairchild proposed that a Japanese “field of cherries” be planted along the Tidal Basin, which was then under construction south of the Washington Monument. The planting took place not long after the conclusion of the so-called Gentleman’s Agreement of 1907, whereby Japan would limit emigration of its working-class nationals to Hawaii and the mainland. The initiative won President Taft’s approval as a gesture of friendship to the Japanese. Pauly observes that “a field of Japanese flowering cherries in Washington was preferable to a settlement of Japanese working families in California.”

Fairchild’s program was in part the product of a shift in plant importation away from Europe and to Asia that had begun during the 1890s. The change had been prompted by word from scientists who had gone to Japan to assist the Meiji modernization that Japanese plants might well flourish in the eastern United States. Fairchild’s principal agent in the Far East was Frank Meyer, an immigrant Dutch gardener whom he hired in 1906. A resilient traveler, competent botanist, hardheaded nurseryman, and skilled deal-maker, Meyer collected plants in China and southern Russia and sent hundreds home. His efforts ended abruptly in 1918 when he drowned in the upper Yangtze River, having fallen, jumped, or been pushed at night from the riverboat on which he was traveling.

Fruits and Plains is an episodic book, but running subtly through it is a reading of “culture” in the American horticultural enterprise as a critique of academic cultural theory, with which Pauly is impatient. He finds that his horticulturists were pragmatists for whom “culture” had multiple meanings. The term referred to the tasks of cultivation—for example, the hard work of planting, hand weeding, and spreading well-rotted manure—that were required to raise fruit trees and vines. It also conveyed a moral purpose, the expectation that the production of exquisite fruits, gorgeous camellias, and velvet greenswards would “lead to higher culture—to the refinement of public taste.”

Culture, in Pauly’s sense, also reflected the tensions in the United States between nativism and cosmopolitanism, between naturalized and alien. The tensions were as palpable in divisions over the importation of plants as they were in conflicts over human immigration. Importation posed not only a cultural but a material threat—the penetration of the nation’s borders by pests that often accompanied the foreign plants. As Pauly writes, the exclusion, suppression, and elimination of destructive agents were essential to the strategy of horticultural independence.

The tensions emerged early in the nation’s history with the arrival of the wheat pest now known scientifically as the gall midge, brought over in British imports of grass from continental Europe to the New York region during the Revolutionary War. By 1786, the midge was destroying wheat and gaining notice. George Morgan, a prominent farmer near Philadelphia, had watched Hessian troops savage the region during the war. Together with a friend he dubbed the midge the “Hessian Fly” even though it had no connection to Hesse. He was eager, as he put it, to express “our Sentiments of the two Animals”—the Hessians and the flies—and “to add, if possible, to the detestation in which the human Insect was generally held by our yeomanry.” The prominent British naturalist Joseph Banks worried that wheat from the United States might bring an infestation to Britain, and successfully urged the Privy Council in 1788 to ban imports of the grain. The next year he justified this order in a report that Jefferson said was a “libel on our wheat.”

Pauly’s account of the dispute, drawing on hitherto unexamined documents from the principals, shows how from the nation’s first years Americans were inclined to perceive threatening pests as “foreign invaders” and to interpret in local terms problems that were global, arising from the movement of people, plants, and insects. Americans were continuously anxious about their future political, economic, intellectual, and botanic independence.

Pests of both foreign and domestic origin continued to threaten American agriculture, but the number of invaders from abroad increased from the late nineteenth century along with the rise in global steamship travel and the expansion of the sources of plant imports. States felt threatened not only by foreign pests but also by those that spread through interstate commerce, which after 1898 included bugs from newly annexed Hawaii. In 1881, California, with its rapidly burgeoning fruit industry, established a State Board of Horticulture with power to suppress infestations—at first of its wine grapes, which were threatened by a root louse (the Phylloxera vastatrix that was wreaking havoc in European vineyards) and then of all commercial fruits. By 1896, fifteen states had passed orchard inspection laws, at least some of which, like California’s board, authorized state agents to spray suspect plants, even against the wishes of the growers.

Pauly notes that state measures to guard against infestations from beyond their borders were made more difficult in the late nineteenth century by the Supreme Court’s increasing protection of interstate commerce from local interference, including the regulation of animal health. Early in the twentieth century, however, Charles Marlatt, who became a high-ranking official in the USDA’s Bureau of Entomology, emerged as a strong advocate for federal regulation of agricultural pests. Like David Fairchild, he came from Kansas, but while Fair- child was a cosmopolitan in his attitudes toward plant importation, Marlatt was a nativist, eager to restrict plant introductions as a safeguard against pests. In 1909, when his bureau found various infestations in the Japanese cherry trees destined for the new Mall, he recommended destruction of the entire shipment, a proposal that Pauly says reflected fears of the Yellow Peril. The trees were burned with President Taft’s approval, but the Japanese sent a new shipment, carefully sanitized, that was accepted and planted in 1912.

That year, largely because of Marlatt’s efforts, Congress passed the Plant Quarantine Act, which gave the USDA unprecedented police powers. As Pauly writes, “its uniformed agents could stop and search individuals, and seize their property, to prevent the spread of pests from one state to another.” Marlatt had been assisted in his cause by mounting concern in California over the arrival from Hawaii of the Mediterranean fruit fly, which feeds on and ruins many different fruits and vegetables. This prompted the state to establish a quarantine division. The federal quarantine act, which included administrative compromises to maintain local control of regulation, contained language specific to the dangerous fly.

In November 1918, in keeping with the spirit of the intensifying immigration restriction movement, Marlatt issued Quarantine 37, an administrative order that, with few exceptions, prohibited entry of foreign nursery stock so as to exclude plant pests and diseases from the United States. The head of the US Forestry Association, which supported the sweeping measure, compared it to the literacy test, calling it the end of the “open door to plant immigrants,” and expressing the hope that “the treasonable activities of these enemy aliens will be curbed.”

Horticulturists and their allies not only established orchards, vines, and grasses in the East, the Midwest, and California but, as Pauly recounts, endowed the hitherto wood-free prairies with timber and fruit trees, developed industries of oranges and semitropical plants in Florida, and sculpted landscaped installations from Hyde Park to Central Park. While some of these episodes are familiar, Pauly breaks new ground by attending less to forests and more to trees—to the decisions made about what to plant and to the cultural values that the decisions revealed.

His examples are telling—for instance, Andrew J. Downing, the influential landscape architect, responded to the Irish immigration in the 1840s by railing against the planting of foreign trees and called on northeasterners to rely on “clean natives.” Harriet Beecher Stowe tried to promote orange groves on the St. John’s River in post–Civil War Florida in the hope of providing an alternative to the slavery-tainted cotton business. In Nebraska, in 1872, J. Sterling Morton, later Grover Cleveland’s secretary of agriculture, initiated what became the nationwide Arbor Day to promote the planting of trees on the prairies for both economic and environmental advantage. J. Horace McFarland, a publisher of horticultural books and magazines, organized a coalition of scientists and amateurs to contest the plant quarantine rules that obstructed their long-standing practice of freely importing and sharing novelties.

The plant quarantine system fell apart in the first half of the 1930s, Pauly points out, undermined in significant part by criticism that it had failed to prevent new pests from entering and spreading throughout the United States. Dutch elm disease came with timber imported from France for furniture veneer. By then the self-conscious drive for horticultural improvement had dissipated, replaced by the penchant of an increasingly suburban nation for gardening and landscape design. In the succeeding decades the United States grew even more globally engaged with plants as with much else.

During the 1990s, Pauly notes, the country was beset by a new wave of apprehension about invasions of “alien species,” a term that implicitly applied to foreigners but that also revived “linguistic links between human immigrants and noxious pests.” In the climate of fear and restriction that enveloped the country, David Fairchild’s response in 1917 to Marlatt’s campaign for what became Quarantine 37 remained apropos: Such exclusions, he said, ran contrary to the “trend of the world…toward greater intercourse, more frequent exchange of commodities, less isolation, and a greater mixture of the plants and plant products over the face of the globe.”

-

1

Lyman Carrier, The Beginnings of Agriculture in America (McGraw-Hill, 1923), p. 41.

↩ -

2

Andrew J. Downing, The Fruits and Fruit Trees of America (Wiley and Putnam, 1845), p. 114.

↩ -

3

Creating Abundance: Biological Innovation and American Agricultural Development (Cambridge University Press, 2008). Other examples of this literature include Deborah Fitzgerald, The Business of Breeding: Hybrid Corn in Illinois, 1890–1940 (Cornell University Press, 1990); Jack R. Kloppenburg Jr., First the Seed: The Political Economy of Plant Biotechnology, 1492–2000 (second edition, Cambridge University Press, 2004); Michael Pollan, The Botany of Desire: A Plant’s-Eye View of the World (Random House, 2001); Steven Stoll, Larding the Lean Earth: Soil and Society in Nineteenth-Century America (Hill and Wang, 2002); Industrializing Organisms: Introducing Evolutionary History, edited by Susan R. Schrepfer and Philip Scranton (Routledge, 2004).

↩ -

4

Jane S. Smith, The Garden of Invention: Luther Burbank and the Business of Breeding Plants (Penguin, 2009).

↩ -

5

On manure, see Steven Stoll, Larding the Lean Earth: Soil and Society in Nineteenth-Century America (Hill and Wang, 2002).

↩ -

6

B. June Hutchinson, “A Taste for Horticulture,” Arnoldia, Vol. 40, No. 1 (January 1980), p. 40.

↩ -

7

Daniel J. Kevles, “Patents, Protections, and Privileges: The Establishment of Intellectual Property in Animals and Plants,” Isis, Vol. 98, No. 2 (June 2007).

↩