I was in Managua, Nicaragua, thirty years ago, recovering from dengue fever, when my editor at The Guardian called from London to say that I should get on the next plane to San Salvador: the archbishop of El Salvador had been gunned down while saying Mass. I remember laughing at the impossibility of this too literary story—murder in the cathedral; of course it wasn’t true!—and then feeling sick. Óscar Arnulfo Romero, a self-effacing, not particularly articulate, stubborn man, who insisted every day on decrying the violence and terror that ruled his country, was, after all, the hierarch of the Catholic Church in El Salvador. Did he not have all the weight of the Vatican behind him, and the natural respect of even the most right-wing zealot for such a holy office? And then there was the act itself: murder at the most sacred moment of the Catholic Mass. Who, in such a Catholic country, would dare to violate the transubstantiation of Christ’s body?

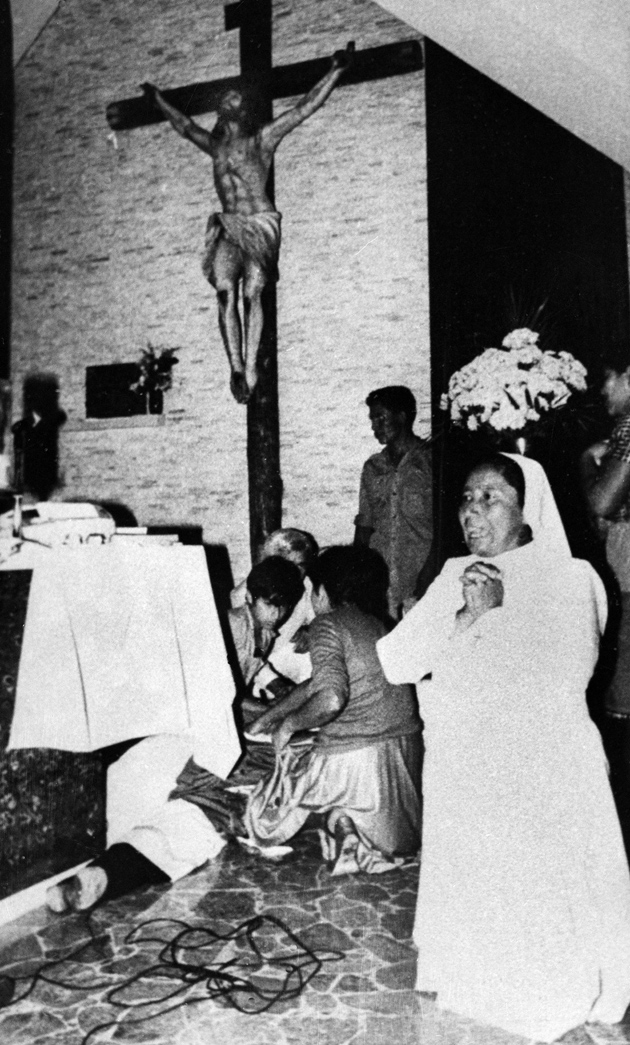

But of course the story was true. Around 6:30 PM on Monday, March 24, 1980, a red Volkswagen Passat drove up to the small, graceful chapel of the Divina Providencia Hospital, a center run by Carmelite nuns where Romero lived. It was, as it almost always is in San Salvador, a hot day, and the wing-shaped chapel’s doors were open. As Romero stood at the altar just after the homily a tall, thin bearded man in the back seat of the Volkswagen raised an assault rifle and fired a single .22 bullet into the archbishop’s heart. Then, in no particular hurry, the car drove away. A grainy black-and-white photograph from that day shows the victim on the floor. As Romero’s heart pumps out the last of its blood, the white-coiffed nuns gather around him like the points of a star, or like the figures at the feet of Christ in Renaissance murals, which were intended simultaneously as representations and as prayers.

Historical turning points are so often the result of stupidity. The Sandinista Revolution, which had triumphed in Nicaragua barely eight months before, had set the dream of revolution flaring across Central America. But Romero’s murder and the mayhem and bloodshed set off by a sharpshooter at his funeral the following Saturday were perhaps the immediate sparks for the bloody twelve-year civil war that started in El Salvador just months later and killed some 70,000 Salvadorans, with the United States providing financial and military backing to the government side. It is hard to overstate how fervently the campesinos of El Salvador believed in Romero and what became known as the Liberation Church. When he was gone, entire villages placed themselves at the disposal of the guerrilla factions, which came together as a united front, the FMLN, a few months later.

The archbishop made a long journey to arrive at his death. During the 1960s and 1970s an assortment of guerrilla groups had attempted to stir poor Salvadorans to revolution, managing only to recruit university students and a smattering of the impoverished working class. Around that same time a great many Catholic nuns and priests, including foreign missionaries, became increasingly radicalized and sympathetic, or even linked to, the guerrilla organizations. By all accounts, the studious Romero was not among them. He was not even attracted to the tenets of what became known as Liberation Theology, the “preferential option for the poor.”

Hardworking and conscientious, he rose through the ranks and eventually became bishop of the rural province of San Miguel, maintaining all the while a strict distance from what he called the left’s “mysticism of violence.” By then, however, the insistent defense of human rights by the new generation of radicalized priests and nuns, and the murderous government’s determination to violate those rights, particularly in the case of the landless peasantry, had created a small army of conscripts for the guerrilla organizations, which promised an equal and just world order born of socialist revolution.

During the presidency of General Arturo Molina (1972–1977), the army and security forces were essentially transformed into death squads: Romero watched in horror as campesinos in his parish were displaced, threatened, terrorized, and increasingly shot, stabbed, or hacked to death by underfed, underage soldiers wielding machetes against their own kind. He began speaking out against these atrocities and received his first death threat (from General Molina himself, who wagged a finger at him and warned that cassocks were not bulletproof). And then, in 1977, just weeks after Romero had been ordained archbishop, the Jesuit priest Rutilio Grande, a close friend of Romero’s who had been organizing landless peasants, was shot down on a country road along with two of his parishoners.

Advertisement

All Romero’s contradictory feelings about church and duty, repression and human dignity, his native distrust of radicalism and politics, his caution and, no doubt, his fear appear to have resolved themselves at that moment. With the same methodical determination that seems to have characterized his rise to the archbishopric, he spent the next three years organizing human rights watchdog groups, asking President Jimmy Carter to suspend military aid to the murderous junta, and speaking out—plainly, but never unreasonably—against the government. “It is sad to read that in El Salvador the two main causes of death are first diarrhea, and second murder,” he would say. “Therefore, right after the result of malnourishment, diarrhea, we have the result of crime, murder. These are the two epidemics that are killing off our people.”

Those were the days before the Internet or even faxes, and the lone opposition newspapers, El Independiente and La Cronica del Pueblo, were more or less gagged. (Its publisher and editor, Jorge Pinto, survived three assassination attempts before going into exile.) The murders and disappearances carried out by death squads, army officers, and a notorious security force called, for inexplicable reasons, the Treasury Police were unreported, but Romero took to reading a detailed account of the week’s brutalities—the dozens of cases of torture and murder of peasants that were by then taking place every day—during his Sunday homilies. The sermons were broadcast by the Catholic radio station, and campesinos all over the country gathered around radios to listen to them. So did the military.

The once conservative archbishop, who had been trained and nurtured not in his homeland but in Rome, became the government’s most visible opponent. Later he would say that when he saw the corpse of Father Rutilio Grande a few hours after his murder, he thought, “If they have killed him for doing what he did, then I too have to walk the same path.”

I had a first understanding of the Catholic Church’s relationship with poor Salvadorans one Sunday in 1978. César Jerez, who was then the superior of the Jesuit Order in Central America, suggested that I travel over back roads to a village deep in the craggy hills of Cabañas province. The Church had been organizing there for years creating “Christian Base Communities” in which villagers learned to read, studied the Bible, and gradually became aware of their rights. But this was not all; the priests—and also, on a smaller scale, the female religious—organized schools, soccer teams, and infirmaries. They set up scholarships in the cities for talented students. They heard everyone’s confession. And they taught, according to the tenets of Liberation Theology, that poor peasants like themselves deserved to inherit God’s kingdom right here on this earth. In response to this wave of radical activism the government and the ruling families of El Salvador set up a peasant paramilitary force called ORDEN (Organización Democrática Nacionalista), which worked hand in hand with the Treasury Police.

On my first trip to Cabañas Father Jerez had provided me with a guide—a young Christian activist—and with him I listened and asked questions in whispers as the villagers snuck into a mud-wattle house where we were hiding. The ORDEN snitches, who were members of their own communities, were all around us, they warned, and they were risking their lives by talking to us. One by one, the victims told the stories of how the killers had taken away one woman’s son and slit his throat, and of how another woman had found her husband in a ditch, “chopped into little bits” by the machetes of the killers, so that she could not even bury his body whole. Finally, they produced statements—this was the Jesuit influence at its most distinctive—meticulously written out in pencil, in which they detailed the date and time of each attack, and listed the treasures that “los ORDEN” had pillaged from them. “I was robbed,” a typical statement would say, “of a dozen oranges and four candles. And they cut up the ropes of my cot, so that I have no bed.”

I made many trips to the countryside after this one (I remember seeing men tie themselves to trees, so that they could farm the miserable patch of land they had inherited without tumbling down a mountainside’s steep incline). But it was only two years later, after Romero’s funeral had dissolved into grim chaos, that I had my first real understanding of the feudal ignorance in which Salvadoran campesinos were kept. As red-robed cardinals from abroad milled around the vast unfinished cathedral together with humble worshipers who had lost their shoes, their false teeth, their satchels, or their eyeglasses in the stampede to escape from a sniper’s bullets, everyone trying to understand what had happened and why, a tiny, trembling man approached my friend the photographer Pedro Valtierra. “Please, my daughter’s lost,” he said, and then he repeated several times, until we understood: “Please use your loudspeaker to call out her name.” He was pointing to Valtierra’s camera.

Advertisement

Thanks to an extraordinary piece of reportage posted last month on the Salvadoran online newspaper El Faro, we know that the tall, skinny shooter who killed Romero was contracted by General Arturo Molina’s son, while the weapon and the getaway car were provided by the drinking buddies and death squad associates of a former army major called Roberto D’Aubuisson. Not that anyone doubted from the moment it happened that the murder was D’Aubuisson’s work. He died of cancer of the esophagus at the age of forty-seven in 1992, but while he lived, this slender, charismatic psychopath was king. Although he was briefly arrested, he was never tried for murder and soon rose to become the head of the Constituent Assembly; he was defeated only narrowly when he ran for president in 1984. Until last year the party he founded, which had its origins in the death squad he also put together, governed El Salvador. (Only this year, after Mauricio Funes, the candidate of the party founded by the guerrillas, the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, won the presidential elections, was there for the first time an official commemoration of Archbishop Romero’s death.)

Over a two-year period, El Faro’s director, Carlos Dada, hunted down and twice interviewed one of the surviving participants in D’Aubuisson’s conspiracy against the archbishop, a former air force pilot by the name of Álvaro Saravia. Four other alleged coconspirators named by Saravia have been killed; another committed suicide. Some, like Mario Molina, General Molina’s son, are enjoying the good life, but Saravia, pursued by his own demons, is living in abject poverty in another Latin American country that is not disclosed in the newspaper’s report. Perhaps out of sheer loneliness, he told his story to El Faro.

Saravia recounts the details about the hit man and Mario Molina’s role in hiring him. He also reveals that an announcement placed in La Prensa Gráfica by Jorge Pinto, the owner of the independent newspaper El Independiente, inadvertently sealed Romero’s fate. Published on the morning of March 24, it informed readers that the archbishop would celebrate a Mass in memory of Pinto’s mother at 6 PM that day, in the Divina Providencia chapel. Hung over after a party with other members of D’Aubuisson’s group, Saravia woke to the news that the boss had ordered Romero’s murder at this conveniently secluded location.

Óscar Romero is one of the four contemporary Christian martyrs depicted above the west door of Westminster Abbey (the others being Mother Elizabeth of Russia, Martin Luther King Jr., and Dietrich Bonhoeffer), and it says something that the admiration of the Anglican Church has been more spontaneous than that of the Vatican.* Karol Wojtyla had been anointed pope in late 1978, and with the assistance of then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger he was busy dismantling the progressive church of Latin America, replacing Liberation Theology bishops with conservative ones, and transferring priests. Pope John Paul II’s response to the crime—he called it “a tragedy”—was hardly as emphatic as his attacks on the pro-Sandinista clergy when he visited Nicaragua four years later. A spontaneous movement in favor of Romero’s canonization has been stalled for years now in Rome.

But for the Church rank and file, Romero has become an extraordinarily meaningful figure, as a quick Internet search of his name can attest. We can find evidence of this in yet another work intended to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of his death: a documentary film, Monseñor: The Last Journey of Óscar Romero, directed by Ana Carrigan and Juliet Weber, and produced by Latin American/North American Church Concerns. The film is, unintentionally perhaps, or at least effortlessly, a hagiography, a record of a saintly life. It is an astonishing compilation of footage from the last three years of Romero’s life, not only of the archbishop himself but of army patrols and mothers of the disappeared and guerrillas on the move—and above all of those unforgettable Masses in which the small, unprepossessing archbishop read out loud the record of the government’s atrocities while hundreds of ragged, persecuted campesinos listened in gratitude, their existence and suffering recognized at last.

I interviewed Romero two or three times before he died, and although I cannot locate any of my notebooks from those dreadful years, I have the distinct recollection that he did not say anything particularly scintillating or inspirational or visionary: he was deeply distrustful of rhetoric and purposefully self-effacing. Instead of words I have the memory of a peculiar ducking gesture he used to make with his head when, after Sunday Mass, he stood outside the cathedral doors shaking hands with the knobby-jointed, malnourished campesinos who came from miles away to hear him, a few coins knotted into their handkerchiefs for the journey back. They would clasp his hand and stare into his face and try to say something about what he meant to them, and he would duck his head and look away: not me, not me.

The day before his murder, on Sunday March 23, after a cropduster had sprayed insecticide on a protest demonstration, and we reporters had gone nearly mad from the obligation to hunt every morning for the mutilated corpses that D’Aubuisson’s people had left at street corners the night before, and distraught mothers lined up every day outside the archbishopric’s legal aid office asking for help in finding their disappeared children, and the waking nightmare of El Salvador clamored to the very heavens for justice, Óscar Arnulfo Romero for the first time spoke in exclamation points in his Sunday homily:

I want to make a special request to the men in the armed forces: brothers, we are from the same country, yet you continually kill your peasant brothers. Before any order given by a man, the law of God must prevail: “You shall not kill!”… In the name of God I pray you, I beseech you, I order you! Let this repression cease!

The next day he was shot.

This Issue

May 27, 2010

-

*

It may have been a shocked archbishop of Canterbury whom I remember in red robes at Romero’s chaotic funeral, as out of place as Santa Claus in the mayhem caused by shots fired into the crowd. ↩