A year ago British Prime Minister Gordon Brown announced a long-awaited inquiry into Britain’s involvement in the 2003 Iraq war, to coincide with the departure of British troops from the country. The Iraq inquiry would be chaired by a retired senior civil servant, Sir John Chilcot—a “safe pair of hands,” the Guardian called him—and would work behind closed doors under arrangements designed to minimize public disclosure of the underlying documents, many of which were classified as “Secret.” Sir John has summarized the inquiry’s mandate as considering “the UK’s involvement in Iraq, including the way decisions were made and actions taken, to establish, as accurately as possible, what happened and to identify the lessons that can be learned.”

At its launch on July 30, 2009, expectations of the inquiry were—to put it generously—low. The carefully chosen composition of the five-member panel did not lead to a quickening of public interest. One member, the historian Sir Martin Gilbert, had previously suggested that Tony Blair and George W. Bush might eventually bear comparison with Winston Churchill and FDR. Another, the academic Sir Lawrence Freedman, contributed to the preparation of the 1999 Chicago speech in which Tony Blair first expressed the emotional and ahistorical interventionist instincts that later led directly to the Iraq debacle. None of the five has any legal background or qualification, as the examination of witnesses—think Gilbert and Sullivan rather than Old Bailey—has shown. The only member to demonstrate forensic ability is Sir Roderic Lyne, a retired diplomat. Most of the key witnesses, particularly the lawyers, politicians, and diplomats, have been adept at swatting away trouble- some questions. More significantly, the inquiry has been undermined by its inability to refer publicly to documents that it has seen and that contradict or undermine witness testimony. It did not seem that its final report, not expected before the end of the year, would be revelatory or forceful.

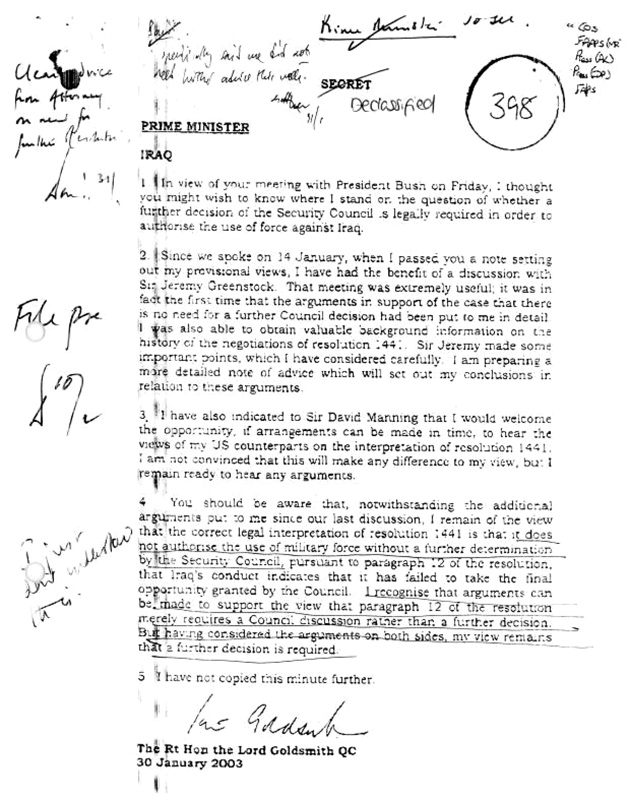

Nevertheless, public and media interest and political pressures have combined to force greater openness than Brown intended. Many—but not all—of the hearings have been public and broadcast on TV and the Internet, and for some appearances—Blair’s and Brown’s in particular—there has been widespread media attention. In recent weeks a growing number of classified documents have been made public by the inquiry, including a damning one-page minute dated January 30, 2003, from Attorney General Lord Peter Goldsmith to Tony Blair. Ending with the words “I have not copied this minute further,” the document is revelatory of the prime minister’s modus operandi, of the tragic weakness of his attorney general, and of the extent to which the British Parliament, Cabinet, and people were misled by these two men. The document, reproduced here on page 56, includes brief, handwritten reactions that are particularly telling. Nothing beats raw material in black and white.

In spite of its limitations, the inquiry has succeeded in teasing out some new information, filling out if not completing a picture the broad lines of which were well known before it commenced. The general conclusions are inevitable and unsurprising: Blair gave Bush an early commitment of support without extracting anything much in return or developing a basis for leverage; he needed to justify his desire to remove Saddam by overstating the very limited and not probative evidence of Saddam’s alleged activity concerning WMDs, and then manipulated its public presentation; he persuaded Bush to go down the UN route, but in so doing he badly undermined his own position by agreeing to a Security Council resolution that his own attorney general told him was an inadequate basis for war; and then he failed to live up to his own expectations of his ability to persuade the Security Council to vote for a second resolution.

As all this was proceeding, and after the invasion took place, he failed to intervene in order to remedy the badly conceived and managed post-conflict situation. Against this background, Blair’s refusal during his public appearance at the inquiry to express any regret whatever for his actions defined a memorable moment. So surprised was Sir John Chilcot that at the end of the session he twice offered Blair an opportunity to express some regret. To the allegations of incompetence, deception, and criminality there are now added the charges of hubris and bad form.

A question that runs through the narrative concerns the legality of a war that was not (and could not be) justified on the grounds of self-defense. The issue won’t go away, and in the British media the conflict is often referred to as “the illegal Iraq war.” Blair justified the war on the grounds that it was authorized by the Security Council. On March 17, 2003, the attorney general, Lord Goldsmith, answered a parliamentary question on the legal authority for war, which was already by then a lively public issue. Without any hint of ambiguity, Goldsmith apparently indicated to the British Cabinet and then to the House of Lords that military force was unambiguously lawful.

Advertisement

His 337 words of reasoning (an advocacy document for which Lord Goldsmith required the assistance of no fewer than nine lawyers and senior civil servants) have the great merit of simplicity: Security Council Resolution 678 authorized the 1990 Iraq intervention and was “revived” as a result of Saddam’s “material breach” of the terms of the subsequent cease-fire. At the heart of the argument is Resolution 1441, adopted unanimously by the Security Council in November 2002. According to Goldsmith, Resolution 1441 gave Iraq “a final opportunity to comply with its disarmament obligations” and determined that a failure to so comply and cooperate would constitute a further material breach of those obligations. “It is plain,” wrote Lord Goldsmith, “that Iraq has failed so to comply,” thus giving rise to a material breach and the revival of the original authority to use force.

Goldsmith’s parliamentary answer simply skated over the key question: Who decides whether Iraq is in material breach, the Security Council or one or more individual members such as the US or the UK? It is virtually impossible to find any seasoned international lawyer in Britain who agrees with Goldsmith’s conclusion, as expressed in the statement of March 17, 2003, that the Security Council did not have to make this decision in the form of a new resolution. It is now clear that until shortly before he put his name to the 337-word statement, he didn’t agree with it either.

Well before the Chilcot inquiry it was known that the attorney general had changed his mind just days before the war. On March 7, 2003, Lord Goldsmith gave the prime minister a secret, thirteen-page memo that essentially concluded that although a “revival” argument could be made, it would probably not be successful if it were to reach a court of law. In other words, the better view was that the war was unlawful.

The full memo was not put before the Cabinet, which, like Parliament, had no inkling about the attorney general’s serious doubts. The inquiry has teased out that Foreign Secretary Jack Straw talked Goldsmith out of sharing his doubts with the Cabinet, reflecting both men’s lack of backbone and their willingness to mislead. Nor was the Cabinet aware of the decisive role played by senior Bush administration lawyers in contributing to Goldsmith’s change of mind. “We had trouble with your attorney,” the legal adviser to Condoleezza Rice—John Bellinger—later told a visiting British official, “we got him there eventually.” Nor did the Cabinet learn of the terms of the resignation letter of the deputy legal adviser at the Foreign Office, Elizabeth Wilmshurst, that elegantly referred to Lord Goldsmith’s late change of mind without revealing the details.

Lawyers are of course entitled to change their minds, and frequently do. New facts emerge, or new legal arguments come to the fore. Between March 7 and March 17, 2003, there were, however, no new facts and no new legal arguments on which Lord Goldsmith could rely. In the intervening seven years he has not been able to provide a convincing explanation for his change of position to rebut the obvious inference that he succumbed to the political pressures that plainly abounded. When Lord Goldsmith appeared before the Chilcot inquiry on January 27, 2010, he was under pressure to explain. His silky performance did not dispel the doubts. He confirmed that his change of mind was largely due to the persuasive arguments of senior Bush administration lawyers, with whom he had met in early February 2003. Tantalizingly, new information did emerge about the views he had expressed in writing before March 7, 2003. This suggested that the inquiry had before it other documents not publicly available. Without being able to refer to the documents, his inquisitors were barely able to lay a glove on the former attorney general.

Then, in May 2010, the Labour Party lost the general election and a new Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition came to power. This appears to have contributed to a decision to declassify documents for which the inquiry, as the Cabinet secretary put it, had waited for “some time.” On June 25, around its first anniversary, the inquiry quietly published a set of documents that laid bare the clear and consistent legal advice that Lord Goldsmith gave to Tony Blair at key moments, from July 2002 right up to February 12, 2003. The documents paint a devastating picture, principally (but not only) emphasizing the attorney general’s sudden, late, and total change of direction. Following a year of consistent advice, he made a 180-degree turn in the space of a month.

Advertisement

The documents laid an unhappy trail. On July 30, 2002, Lord Goldsmith wrote the prime minister that self-defense and humanitarian intervention were not admissible, and that military action without explicit Security Council authorization would be “highly debatable.” On October 18, 2002, he told Straw that the draft of Security Council Resolution 1441 “did not provide legal authorisation for the use of force,” and that the British government must not “promise the US government that it can do things which the Attorney considers to be unlawful.” On November 11, 2002, immediately after Resolution 1441 was adopted, he told Jonathan Powell (Blair’s chief of staff) that “he was not at all optimistic” that there would be “a sound legal basis for the use of force against Iraq.” At a Downing Street meeting on December 19, 2002, Goldsmith declined to tell those present that they would have a green light for war without a further resolution. On January 14, 2003, he wrote a draft memo that concluded unambiguously that “resolution 1441 does not revive the authorisation to use of force contained in resolution 678 in the absence of a further decision of the Security Council.” These words directly contradict what he would later tell the Cabinet and Parliament.

Which brings us to the most devastating document, Goldsmith’s January 30, 2003, one-pager to Blair, written the day before Blair’s meeting with President Bush at the White House. Lord Goldsmith explained that “I thought you might wish to know where I stand on the question of whether a further decision of the Security Council is legally required in order to authorise the use of force against Iraq.” His conclusion? “I remain of the view that the correct legal interpretation of resolution 1441 is that it does not authorise the use of military force without a further determination by the Security Council.” Clear, unambiguous, and without caveat. The published version of this message, reproduced on this page, includes the gloriously graphic handwritten reactions of three key players.

In the top left-hand corner, Sir David Manning, Blair’s principal foreign policy adviser, notes: “Clear advice from Attorney on need for further Resolution.” Alongside, Matthew Rycroft, who served as Blair’s private secretary, sounds irritated: “Specifically said we did not need further advice this week” (apparently confirming allegations that Blair did not want a paper trail of early, unhelpful advice). And on the left-hand side of the minute, with Goldsmith’s damning conclusions underlined by the same hand, these scrawled words: “I just don’t understand this.” The handwriting is Blair’s, and it is difficult to see quite what he might have had trouble understanding. Lord Goldsmith’s words—consistent with every view he had expressed over the previous six months—admit of no doubt, adopting the views taken by the UK since 1990, by the Foreign Office legal advisers, and by virtually every international lawyer in Britain (if not the world, outside of the US). What Blair seems to be saying is that he doesn’t understand why this wretchedly unhelpful view was reduced to writing at that key moment.

The timing could not have been worse. The next day, on January 31, 2003, Blair met Bush, accompanied by Sir David Manning and Matthew Rycroft. Sir David wrote up a widely reported five-page note of the meeting that is before the inquiry but has not yet been made public in full. Sir David records the President telling Blair that the US would put its full weight behind efforts to get another Security Council resolution but if that failed, “military action would follow anyway”; that the “start date for the military campaign was now pencilled in for 10 March,” which was “when the bombing would begin”; and that the “diplomatic strategy had to be arranged around the military planning.”

Sir David then records Blair’s response, stating that he was “solidly” with the President and ready to do whatever it took to disarm Saddam. He wants a second resolution “if we could possibly get one,” because it would make it much easier politically to deal with Saddam, and as an insurance policy “against the unexpected.” According to the memo, the prime minister completely ignores the views of his attorney general, who has told him only the previous day that a further resolution is necessary to act lawfully, not merely desirable.

It is against this background that the attorney general’s sharp change of mind will surely haunt him. After Blair’s meeting with Bush, the attorney general went to the US to meet the Bush administration lawyers (he made no similar trip to any other country, whose lawyers would no doubt have held rather different opinions). He told the Chilcot inquiry that it was their views that caused him to abandon his long-held position. Yet many of the Bush administration’s lawyers with whom he engaged were among the officials who failed to prevent the Bush administration’s descent into serial illegalities in 2001 and 2002: ditching the Geneva Conventions, imprisoning suspects at Guantánamo without granting them minimum rights, and embracing waterboarding and other acts of obvious torture. Goldsmith has spoken out against all these measures. Just why he would find the US lawyers’ views on the use of force any more convincing is a question that seems to admit of only one answer. Many have concluded that he was accommodating the desires of the prime minister.

The Chilcot inquiry has given us all we need on this dismal story: the evasive testimonies and the few but damning documents provide an incontrovertible account. The proceedings of the inquiry decisively expose the lamentable and dysfunctional processes that brought Britain into such disrepute, even if its mandate and its members’ lack of formal legal qualifications necessarily mean that it has no particular authority to express a view on the legality of the war. (In January 2010 a parallel Dutch inquiry chaired by a retired Supreme Court judge and largely composed of lawyers concluded that the war was illegal, contributing to the downfall of the Dutch government.)

In late July, Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg, standing in for Prime Minister David Cameron at the Dispatch Box in Parliament, described the war as “illegal.” When asked for clarification about whether this was now British government policy, the official spokesman conspicuously failed to back Blair and Goldsmith and to defend the war as lawful, indicating instead that the new government would prefer to await the outcome of the Chilcot inquiry. A spokesman for the inquiry was then reported as saying that Sir John would not make a conclusion on whether the war was legal. In British parlance, this is what’s called a dog’s breakfast. In any event, the British have come to be deeply skeptical about such inquiries. In the court of public opinion, for this one in particular, the process and its revelations may be more significant and lasting in their effects than any final report that eventually emerges.

—August 31, 2010

This Issue

September 30, 2010