1.

No one who experienced the elated atmosphere of the American presidential election two years ago and who had also been in London in May 1997 could fail to be reminded of the similar mood when Tony Blair won his first general election. He makes the comparison himself. Just as Blair had once been, Barack Obama was greeted by adoring crowds “giving all that you touch something akin to magic.” Blair’s election had “felt like a release, the birth of something better than what had been before,” he writes, and the word “release” is right. After eighteen years of Tory rule, most British voters badly wanted a new government.

But the personable man who entered Downing Street just before his forty-fourth birthday was in many ways an unlikely figure. Blair’s father, who was born poor in Glasgow (and was a youthful Communist), rose to be a prosperous barrister, had hoped to be a Tory MP before he was incapacitated by a stroke, and gave his son the education he had lacked. After attending Fettes, the Edinburgh public school, and Oxford, Blair became a barrister and joined the Labour Party, although he had no roots in the movement or obvious political convictions. In an aside at the end of his memoir, he remarks that he has always been more interested in religion than politics, and he entered Parliament almost by inadvertence.

When I first came across Blair he was standing unsuccesfully in a by-election in 1982. He was elected the following year in an otherwise disastrous general election for his party—Margaret Thatcher’s second triumph—when “I didn’t really think a Labour victory was the best thing for the country, and I was a Labour candidate!” He joined opposition benches much diminished in talent; soon afterward, the Tory politician and diarist Alan Clark spotted “two bright boys called Brown and Blair” among Labour freshmen, and both their stars steadily rose.

After Labour lost again in 1987 and then in 1992, Neil Kinnock resigned the leadership, and John Smith was elected in his place, although Blair considered Smith the real culprit for the latest defeat. Smith had proposed higher taxes for the better-off, which was “great for the party faithful” but electorally disastrous, thought Blair, who saw the need entirely to remodel Labour, discarding its social democratic heritage and offering a sanitized form of Thatcherism. Even he could scarcely have foreseen that “New Labour” under his leadership would win three elections and that he would serve as prime minister for ten years, or where those years would take him, and us.

2.

Apart from the delightful My Early Life, Churchill wrote no memoirs as such, even if A.J. Balfour wisecracked about his “history” of the Great War that “Winston has written an enormous book about himself and called it World Crisis.” But every other prime minister in office from 1945 down to Blair has written memoirs, and grim reading most of them are, whether by Anthony Eden or Harold Macmillan. Not only did Blair want to write something different, he says, he wanted to write it himself. Alas, those worthy intentions give us a book written in a manner that is not so much conversational as rambling or downright incoherent. It’s like being trapped by the pub bore, who also wants to share his excruciating confidences. Yes, “the prime minister has sex,” he tells us after his wife becomes pregnant; or, of an earlier night, “I needed that love Cherie gave me, selfishly, I devoured it to give me strength, I was an animal following my instinct.”

But then comes an alarmingly dis- concerting turn: Matey Tony becomes Blair Exalted, as he finds his Destiny. Visiting Parliament when young, he “had a complete presentiment…. This was my destiny.” Years later, “I felt a growing inner sense of belief, almost of destiny,” in the way that “an artist suddenly appreciates his own creative genius.” Blair had no reason to know that Smith would die suddenly aged only fifty-five, “except that, in a strange way, I began to think he might.” By now Blair was charged “with this curious sensation of power, of anticipation, of prescience. Then John did die.”

That was 1994, when Brown and Blair were the obvious candidates for the party leadership, but Blair persuaded Brown to stand aside in return for a loose promise that he would later become prime minister after Labour had taken office. As the title of The Third Man unblushingly implies, Peter Mandelson helped create New Labour, supporting first Brown and then Blair, before he was twice appointed to the Blair Cabinet, and twice sacked. Mandelson now acknowledges that the original deal with Brown was a grave error on Blair’s part.

Advertisement

He did not want to compete directly with Brown, Blair writes, because he “was scared of the unpleasantness…of two friends becoming foes.” But why? Until then, Labour had known open, fair contests for the leadership, from 1935, when Clement Attlee defeated Arthur Greenwood and Herbert Morrison (Mandelson’s grandfather), both of whom later served in his Cabinet, until 1976, when James Callaghan defeated five others who all remained in his Cabinet. Far from being pushed aside, Brown should have been obliged to stand against Blair for the party leadership. He would without doubt have been decisively beaten by Blair, and could never have nursed his imaginary but corrosive grievance of having been cheated of a rightful prize.

As it was, “the unpleasantness…of friends becoming foes” is horribly ironical. Andrew Rawnsley’s The End of the Party, a fly-on-the-wall account of the later years of the Labour government by the political columnist of the Observer, is dominated by the savage feud between Blair as prime minister and Brown as chancellor of the exchequer, which steadily poisoned relations between them. But then it also dominates The Third Man, and much of A Journey.

Since the prime minister and chancellor are the two most important members of a British Cabinet, a harmonious relationship between them is essential if the government is to function properly. If there’s disharmony, the chancellor usually resigns, or is removed. In 1958 there was a “little local difficulty,” in Harold Macmillan’s misleadingly breezy phrase, when his chancellor, Peter Thorneycroft, resigned in protest at inflationary policies, and in 1989 more than another little difficulty when Nigel Lawson resigned as Margaret Thatcher’s chancellor, to her grave discomfort. An interminable vendetta can only hobble the government, which is what happened.

For years, Blair and Brown were barely on speaking terms, although they were often on screaming terms. Mandelson describes a characteristic meeting in November 2000 with Brown shouting at Blair, “It’s about time you fucking realised that’s all the election is about,” meaning his own supposedly successful conduct of the economy. And so on, and on, until the choicest line in The Third Man: “As Tony dealt with the twin pressures of Gordon and Saddam Hussein…”

While Mandelson gives an indelible portrait of Brown as a man almost unhinged, he also, intentionally or not, portrays Blair as a weakling, quite unable to curb such destructive disloyalty. Blair himself can offer no explanation of his inertia, except that Brown was “an outstanding Chancellor.” Blair seems unaware that, despite the increased prosperity after 1997, the supposed economic miracle now looks much less rosy, following the financial implosion for which Brown, who delighted at the time in the fiscal fruits of unregulated and reckless “casino capitalism,” must bear large responsibility.

And yet there may be another reason. Until becoming prime minister, Blair’s concerns had been entirely domestic, from “tough on crime” to reform of public services and welfare, and he had little interest in (or knowledge of) foreign policy. Finding himself thwarted by Brown at home, Blair turned his gaze abroad.

3.

One day, the feud between Brown and Blair will seem an esoteric episode of British political history. Iraq will not. With his interventions in Kosovo in June 1999 and in Sierra Leone in May 2000, Blair had acquired a new sense of mission—and a relish for military force. Then came September 11, and another vision. “I felt eerily calm” on hearing the news from New York; “there was no other course; no other option; no alternative path. It was war.”

Already imbued with an intense, though historically ignorant, loyalty to the United States, Blair flew to the stricken city and gave a speech on Fifth Avenue that he still quotes with pride: “My father’s generation went through the Blitz…. There was one country and one people which stood by us at that time. That country was America and those people were the American people.” We have become aware of how little history Blair knew, but even he might have heard that the United States remained conspicuously, and profitably, neutral while the Blitz was raging in 1940–1941.

Such ignorance might have been merely risible had it not been for its implications. Ever since Churchill, British policy has been bedeviled by a “special relationship” that was special largely in that only one side knew it existed. Like most great powers, the United States ultimately pursued its own interests, regardless of friends, let alone foes, and the Americans humored the British while ignoring them for practical purposes. It has been the repetitious theme of former ambassadors and other witnesses at the recent Chilcot inquiry into Britain’s part in the Iraq war that Blair gained nothing whatever from the Bush administration in return for his unswerving support, and indeed exerted almost no influence at all in the White House. With Iraq, the special relationship met its nemesis.

Advertisement

But Blair could influence others. More articulate than the President and, unlike him, admired by many liberals or progressives, he could crucially speak to opinion, American as well as British, far beyond the reach of Bush. Back home, he gave, in his own phrase, a visionary speech to his party conference:

The starving, the wretched, the dispossessed, the ignorant, those living in want and squalor from the deserts of Northern Africa to the slums of Gaza, to the mountain ranges of Afghanistan: they too are our cause…. The kaleidoscope has been shaken. The pieces are in flux. Soon they will settle again. Before they do, let us reorder this world around us.

The next morning the Tory Daily Telegraph acclaimed “Blair’s Finest Hour”—one of many Churchillian invocations at the time—but more significantly, a columnist in the liberal Guardian saluted the speech as the “moment British politics became vigorously, unashamedly, social democratic. The day it became missionary and almost Swedish in pursuit of universal justice.”

In Washington, the administration was already plotting military action against Iraq—whatever weapons Saddam did or did not possess, with or without the support of the United Nations—as Blair well knew, since President Bush had told him so. And so while Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, and the neoconservatives planned a war for their own purposes, Blair’s task was to sell this war to people who believed in social democracy and liberal values.

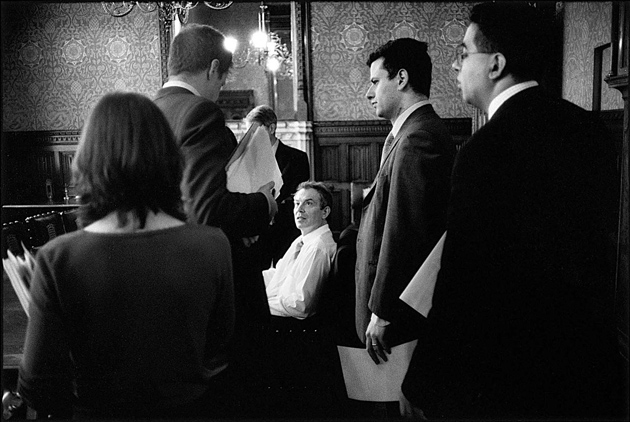

Nick Danzinger/Contact Press Images

Tony Blair with Alastair Campell (second from left) and other aides in the prime minister’s office at the House of Commons, minutes before Blair delivered the speech in which he declared his decision for Britain to join the US in the invasion of Iraq, March 18, 2003

He ardently supported unilateral action, but he also knew that his enthusiasm was not shared by most British people, from the voters—a poll on January 21, 2003, found 30 percent in favor of war and 43 percent against—to his closest colleagues. Andrew Adonis was head of Blair’s policy unit, and Sir Stephen Wall of the Foreign Office was then a senior adviser at Downing Street, “very professional and proficient,” says Blair. He does not add that Wall, like Adonis, was opposed to the invasion, although Wall also knew better than most that “Blair had made up his mind in the middle of 2002 that he was going to war.”

Even the loyal consigliere was skeptical. Traveling in Asia, Mandelson learned for himself that most Muslims saw the coming war as “a crusade of convenience” against an Arab state whose antipathy toward Israel and distrust of America they shared: “This worried me.” But when he said so in the garden of Number 10, Blair rolled his eyes and replied, “For God’s sake, have you been spending all your time with George Galloway?”—the sometime Labour MP who had praised Saddam.

In March 2003, on the eve of the invasion, Robin Cook, who had been Blair’s first foreign secretary, resigned from the Cabinet in protest, and 139 Labour MPs voted against the war, the largest rebellion in a governing party since the Liberals split over Irish Home Rule in 1886. But such forlorn gestures only emphasized the larger breakdown of Cabinet and parliamentary government, which enabled a lone crusader to take his reluctant country to war.

4.

At this point in A Journey, having already switched from rambling raconteur to wild-eyed seer, the author now turns into Mr. A.C.L. Blair, Barrister at Law—a blustering and shifty counsel in his own defense, evasive, devious, and disingenuous, not surprisingly since he knows how thin his case is. His account is at least as notable for what it doesn’t say as for what it does, and to see the missing pieces we need to compare his version with others.

Although Blair disdainfully describes the way Jacques Chirac tried to forestall the invasion, for example, he doesn’t so much as mention his last meeting with the French president before the war began, at Le Touquet. Rawnsley quotes Stephen Wall, who was present. Chirac warned that the Americans and British were deluding themselves if they thought they would be welcomed in Iraq, and asked whether Blair realized that an invasion might precipitate a civil war. As they left the meeting, Blair turned to Wall and said, “Poor old Jacques, he just doesn’t get it, does he?” To which Wall adds drily that Chirac “got it rather better than we did.”

Then again, Blair brushes aside the question of the legal status of the war, and the mysterious manner in which Peter Goldsmith, the attorney general, suddenly changed his opinion in March 2003. There is an “ingrained myth” that the war was illegal, Blair airily says, and “that Peter really thought so and that he was pressured into changing his mind…. The truth is he was, and is, someone of genuine integrity.” It was bad luck for them that A Journey appeared just as Philippe Sands, the eminent English jurist, published his formidable essay in these pages revealing what the attorney general actually wrote,1 and demonstrating from documentary evidence that the “myth” about Goldsmith is the plain truth. Blair does not quote Goldsmith’s first opinion, cited by Sands, stating that there was no legal basis for an attack. Nor does he mention the view of the late, immensely respected law lord Tom Bingham that the war was “a serious violation of international law.”

And so what more have we learned since about Blair’s personal honesty? Although he devotes many sinuous pages to the question of “weapons of mass destruction,” he now seems bored by the whole business. He patronizingly dismisses the UN chief weapons inspector Hans Blix as “a curious fellow” who tried to impose his own tedious conscientious worries on the heroic war leaders. But Blix has courteously shown that what Blair says about the UN inspections is untrue. Blair does not even mention that by March 2003 Blix’s team had made inspections of five hundred sites, including those suggested by intelligence agencies, and found nothing; he asked for “months,” not years, to complete his work, and was soon told by Washington to leave Iraq.

Unlike Blix, David Kelly, a scientist working for the British government, can no longer speak for himself, and his name haunts Blair still, the more so since one devastating detail has been unearthed about the events leading up to Kelly’s death. In September 2002 the first salvo of Downing Street’s propaganda barrage against Iraq was fired with the “dossier” of alleged intelligence. Blair wrote the preface: “The document discloses that [Saddam’s] military planning allows for some of the WMD to be ready within 45 minutes of an order to use them.”

With odious flippancy he now calls this “the infamous forty-five minutes claim,” but says that it was “not even mentioned by me at any time in the future.” That is not simply disingenuous, it is disgraceful. Like the subsequent, grotesque “dodgy dossier,” cobbled together from outdated Internet material, this statement was publicized by Alastair Campbell, Blair’s mephitic and mendacious press officer, whom he ludicrously calls a “genius” with “clanking great balls.” (There’s a lot of that, what with Bush praising Blair’s “cojones,” and Blair also admiring Rupert Murdoch because “he had balls.”)

But of course that one phrase was trumpeted in the press, as Blair and Campbell knew perfectly well it would be: the Evening Standard headline duly shouted “45 Minutes from Attack,” and the Sun announced, “Brits 45 Mins From Doom.” Blair’s wild claim horrified those who knew the truth. Kelly was employed by the government as a leading scientific authority on advanced weaponry. He regarded Saddam as a menace but, having visited Iraq often, he knew how patchy and insubstantial the evidence was that Saddam had by then anything that could be called a WMD program.

It was thus essential for Downing Street to silence anyone who had such well-informed doubts, men like Kelly and Brian Jones, who was then a member of the scientific directorate of the Defence Intelligence Staff and has now given his revealing and angry account in Failing Intelligence. He was foolish to have assumed, Jones writes, that the forty-five-minute phrase “would easily be spotted as extravagantly inflammatory.” But then Jones holds only a Ph.D. for work on alloys used in nuclear reactors, not a spin-doctorate. At the time he did not feel he could intervene, but he now concedes bitterly that “Alastair Campbell was bloody good at his job,” which was to mastermind “the intricate fabrication of a case to support an invasion of Iraq.”

On May 29, some weeks after that invasion had begun, the BBC journalist Andrew Gilligan said that Downing Street had “sexed up” its evidence about WMDs, notably the forty-five-minute claim. Campbell unleashed a campaign to crush the BBC, or to “fuck Gilligan,” as Campbell predictably said, by exposing and denigrating his sources. It was soon learned that Gilligan had spoken to Kelly, who was publicly identified and bullied by a parliamentary committee. With that done, Blair flew to Washington and addressed Congress.

“I feel a most urgent sense of mission about today’s world,” he said, adding a sycophantic little joke—he’d been reminded that British troops had burned the Capitol in 1814: “I know this is kind of late, but sorry”—and received one ovation after another. He then flew on to Tokyo, to learn that Kelly’s body had been found in a field near his house, with his wrist cut. Blair was speechless when a reporter asked, “Have you got blood on your hands?” On the subsequent flight to Hong Kong, Blair walked back to talk to the journalists. When one asked, “Why did you authorise the naming of David Kelly?” he answered, “That is completely untrue,” and repeated, “Emphatically not. Nobody was authorised to name David Kelly.”

An inquiry was held under Lord Hutton, whose report in January 2004 seemed to contradict most of the evidence he had heard by exonerating Downing Street and censuring the BBC. Most of the press called this report a whitewash, with polls suggesting that the public agreed, and Blair writes that he is still angry about such “brutal media allegations.” One or two journalists did defend Hutton and Blair, and damned their colleagues, with one particularly vehement column appearing in the Financial Times. It was written by Andrew Gowers, that paper’s editor at the time, and berated Gilligan “for casting doubt on government claims about Iraqi weapons of mass destruction.” Soon after this, Gowers was dismissed from the paper and found his metier in corporate public relations, first for Lehman Brothers and more recently for BP.

But go back to Blair’s statement “Emphatically not. Nobody was authorised to name David Kelly.” Rawnsley has now firmly established that on July 8, less than three weeks before those words were spoken, there was a small secret meeting at Downing Street where it was decided that Kelly’s identity must be revealed. The meeting was chaired by the prime minister, Tony Blair.

5.

In a television interview last December, Blair at last came very close to admitting that the war had been fought on a pretext. Asked whether he would still have supported the invasion “if you had known then that there were no WMD,” he answered: “I would still have thought it right to remove him. I mean obviously you would have had to use and deploy different arguments.” Yes, you would—but where do those words leave those people who had supported the war because they believed his WMD claims, and for that reason alone?

If there’s a poignant line in A Journey, it describes one of the last rows with Brown: “He felt I was ruining his inheritance and I felt he was ruining my legacy.” Brown’s “inheritance” came, with poetic justice, after he had at last taken over from Blair. Some of his achievements were real, but too many of them were exposed by the crash of two years ago, which revealed among other things that, in the fat years of plenty and vast tax revenues, Brown had lost control of public finance.

And Blair’s legacy? He says that Labour lost the election last May because under Brown, who finally replaced him as prime minister in June 2007, “it stopped being New Labour.” Blair doesn’t spend much time in his own country nowadays, as he travels the world, ostensibly bringing different faiths together as well as accumulating a large private fortune. Had he been at the Labour conference of September 2009 he would have found it indeed true that “the age of New Labour is over,” as one commentator observed, adding that the entire party from left to right was at least now united in recognizing that “Blair’s doctrine of ‘liberal interventionism’ is one part of the inheritance that should be dumped.”

Then this September, Labour chose Ed Miliband as leader rather than his elder brother David Miliband, the anointed heir of Blair, in whose office David had worked as an adviser before becoming an MP. This choice was an open repudiation of both Blair and the war, as Ed Miliband made clear in his acceptance speech: “I’ve got to be honest with you about the lessons of Iraq…. I do believe that we were wrong…. Wrong because that war was not a last resort.”

Honesty about the lessons of Iraq is nowhere to be found in A Journey. Blair refuses to express any regrets for the chaos and carnage wrought by the invasion, or to consider that he might ever have been in error. We have recently seen copious and horrible new evidence of the civilian death toll in Iraq, of torture, rape, and murder in which the coalition forces were complicit; and although the refugees from the war are little noticed, some 2.5 million of them live miserably in Syria and Jordan. We see every day that the power of Iran has grown steadily as a result of the war, not only in Iraq but in Lebanon and other parts of the Middle East. But if he apologized for—or even acknowledged—any of that, Blair insists, “those who had opposed the war would rejoice,” and that would never do. Is it any wonder that, if his election as prime minister had once felt like a release, his departure ten years later was even more of one?

Having once been impelled by destiny, Blair now invokes history. Just before the invasion, he said that he was “prepared to be judged by history,” adding in his speech to Congress that, even if the ostensible reasons for the war proved untrue, “that is something I am confident history will forgive.” But when so much dishonesty has caused so much suffering, history can be very unforgiving.

This Issue

December 23, 2010

-

*

See Philippe Sands, “A Very British Deceit,” The New York Review, September 30, 2010. ↩