One of the indirect consequences of the latest horrifying bloodshed in the Holy Land has been to intensify responses far away. Divisions of opinion have been so acute and arguments so fraught as to threaten relations among friends or within families. To be sure, such divisions have happened before: the Spanish Civil War caused bitter quarrels far from Spain; twenty years later the Suez Crisis caused more angry dissension in England, and so, in the following decade, did the Vietnam War in America.

But no such episode has ever quite matched what history still knows simply as l’Affaire: the controversy provoked by the conviction for treason of the French army captain Alfred Dreyfus in 1894 and the resulting campaign to exonerate him. The Affair rent France, dividing friend from friend, brother from brother, the Dreyfusard Claude Monet from the anti-Dreyfusard Paul Cézanne, Proust’s Duc de Guermantes from his Prince de Guermantes. At its height in 1898 a cartoon by Caran d’Ache entitled “A Family Dinner” had two panels. In the first all the family are sitting harmoniously around the table over the warning words “Above all! Don’t talk about the Dreyfus Affair!”; in the second they’re screaming and brawling over the caption “They mentioned it…” Change “Dreyfus” to “Gaza” and plenty of families would understand that today.

The Affair not only echoed across the world at the time, from Paris to New York to Vienna to Ukraine; it has a strikingly contemporary resonance. Among the correspondents who covered it were Theodor Herzl and Max Nordau. Shortly afterward they launched the Zionist movement, which eventually led to the creation of a Jewish state. It was thus not only the defining episode in the history of the French Third Republic; it acquired huge significance in Jewish history, and even in world history. At its center was a man who never sought any fame or wished to represent any cause, and indeed “would not have wanted to be the subject of this book,” Maurice Samuels writes. His Alfred Dreyfus, in the Yale Jewish Lives series, is an admirable introduction not only to its nominal subject but to those great historical events. It is an irony that, as Samuels writes, “rarely has so private a person been forced to live so public a life.”

That unwilling celebrity was born in 1859 in Mulhouse in Alsace, a province of the Holy Roman Empire until it was conquered by France in the seventeenth century. Louis XIV’s infamous revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, which ended the toleration of Protestants decreed by Henry IV in 1598, didn’t apply in Alsace, where Protestants thrived. By the nineteenth century Mulhouse—“the Manchester of France,” in the slightly exaggerated phrase—had a vigorous textile industry owned by Protestants and some Jews, such as Raphaël Dreyfus. Then, in 1870, Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck slyly maneuvered the absurd Napoleon III into war, and the French armies were routed. Raphaël’s son Alfred was ten at the time, and he said that watching Prussian troops march into Mulhouse was the “first sorrow” of his life.

Military defeat was followed by France relinquishing Alsace to the new German Reich, and Alsatians had to choose whether they wished to remain French or become German. Raphaël decided that his eldest son, Jacques, should remain in Mulhouse running his cotton mill while the rest of the family tried to secure French citizenship. Alfred and his brother were sent to board at the Collège Sainte-Barbe in Paris. A solitary figure who rarely made friends and felt a “sense of isolation throughout his life, whenever he left the intimate circle of his family,” Alfred was nevertheless determined to join the army by way of the École Polytechnique, one of the grandes écoles that were a legacy of the Revolution and that became, and remain, the summit of the French educational system, rather like the Ivy League or Oxbridge, although the French colleges were always more meritocratic and technocratic, not least in their readiness to admit Jews.

Starting in the artillery, Dreyfus enjoyed what seemed at first a promising military career. He was praised by his superiors for his intelligence and diligence. In 1890 the thirty-year-old Captain Dreyfus was accepted into the École Supérieure de Guerre (the French staff college) and got married. His bride, Lucie Hadamard, was the cousin of a classmate and the daughter of a rich Jewish diamond merchant. By the beginning of 1894 Dreyfus’s ability had won him a two-year junior posting on the General Staff under Commandant Georges Picquart, whom he knew already as an instructor. In that position he won more praise: “Officer with a future,” said one commendation with painful dramatic irony, since that was all too true, if not the future anyone could have imagined.

Advertisement

When Dreyfus received an order on Saturday, October 13, 1894, summoning him to the Ministry of War on Monday at 9 AM wearing civilian clothes, he was merely puzzled. He was met by Picquart and led to an office where four unknown men awaited, also in civilian clothes apart from Commandant Armand du Paty de Clam, who asked him to take down a letter he dictated to the chief of the General Staff. Another officer, Commandant Hubert-Joseph Henry, was watching behind a curtain. After he finished dictating, Du Paty de Clam placed his hand on Dreyfus’s shoulder and said, “I arrest you; you are accused of the crime of high treason.” The charge was that Dreyfus’s handwriting on the letter matched that on an incriminating bordereau, a word—meaning a memorandum containing, in this case, military information—that would become internationally famous.

Amid what would be so much speculation, obfuscation, and plain mendacity, what was true was that the Germans were spying on the French and the French on the Germans. There was indeed someone in the French army who was passing secret information to the German embassy in Paris. Some of these documents were torn up and thrown in a wastebasket at the embassy, and a cleaning woman passed on the pieces to French military intelligence.

One day the cleaning woman brought her contact the torn-up bordereau. Suspicion fell on Dreyfus, although objectively considered he was a most unlikely culprit. Traitorous spies are motivated sometimes by ideology and sometimes by greed. Dreyfus was an ardent French patriot whose substantial income from the family firm, while it might have been resented by less fortunate officers, made him invulnerable to financial subornation. All that was ignored.

In December Dreyfus was given a brief private court-martial. Other officers testified on his behalf, but the prosecutors had by then found what they considered another damaging piece of evidence. In a twist that a novelist or screenwriter wouldn’t dare make up, the German and Italian military attachés in Paris, Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen and Alessandro Panizzardi, were not only confrères but lovers, exchanging ardent notes addressing each other as “dear little girl” or “bugger.” One of these intercepted billets-doux contained information about plans for French military fortifications that had come from “ce canaille de D” (that scoundrel D). Henry claimed that “D” was “Dreyfus,” although he knew very well it was an officer named Dubois.

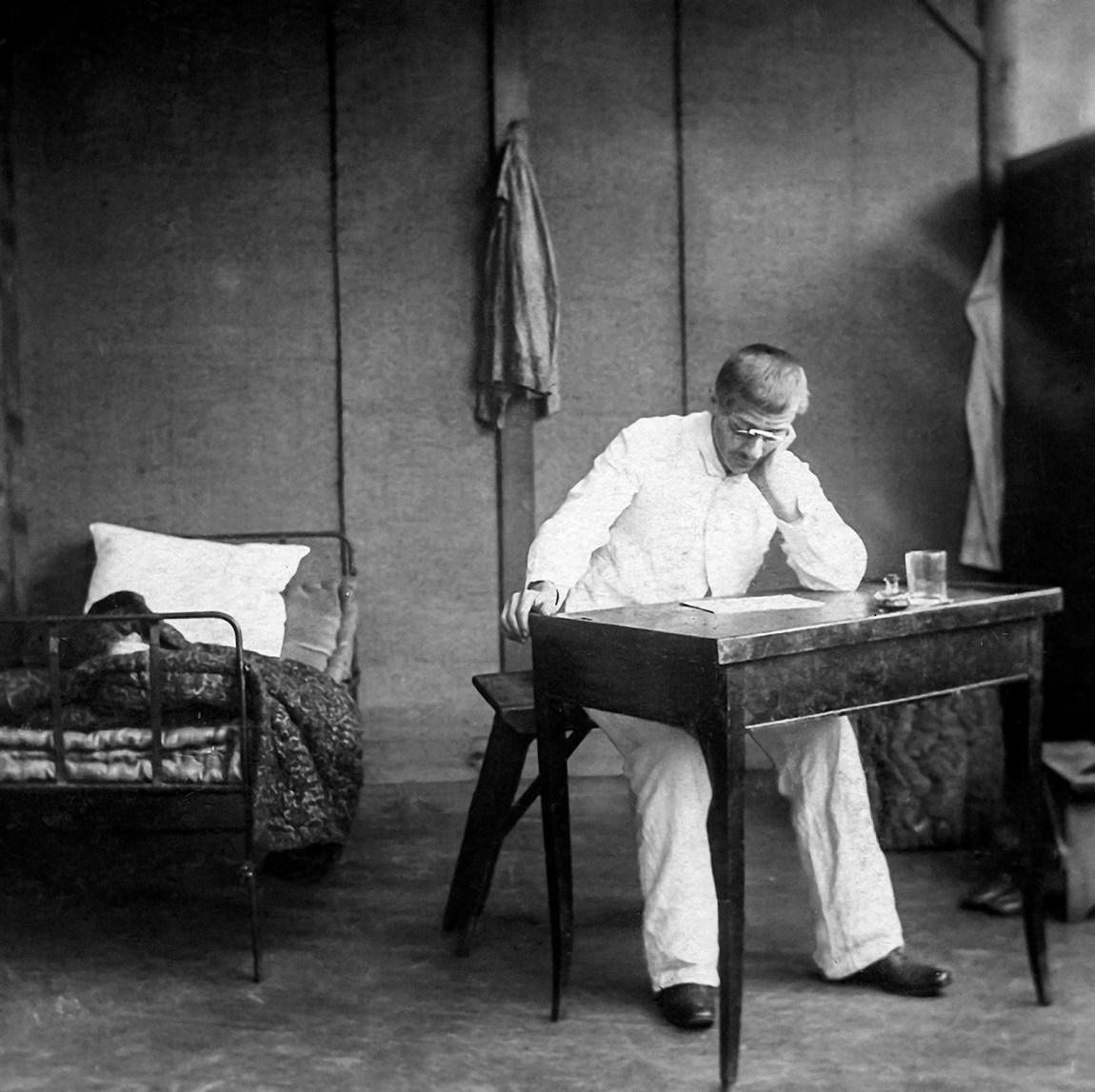

Dreyfus was found guilty. On the morning of January 5, 1895, in the courtyard of the École Militaire, with hundreds of soldiers drawn up and a baying mob outside the gates, he was formally degraded: his officer’s epaulets and stripes were torn off and his sword was taken by a guard and broken over his knee. Though he probably couldn’t be heard over the screams, he shouted, “Soldiers, an innocent man is being dishonored. Vive la France! Vive l’Armée!” He was transported to the penal colony on Devil’s Island, off the coast of French Guiana in South America. Had the death penalty not been abolished for political crimes, Dreyfus might have been shot, but Devil’s Island was the next best—or worst—thing: its climate and the cruelty of the guards meant that there was a very high death rate among inmates.

Although contemporary observers found little imposing or noble about Dreyfus in person, the fortitude and strength of character he displayed during his four years of solitary confinement, afflicted with dysentery and surviving on coarse rations, were surely heroic. In a further torment his guards locked his legs to his bed at night so that he couldn’t move as insects crawled over and bit him. As Samuels rightly says, if France was able in the end to affirm its commitment to human rights, “it was only because of the will of this particular man to resist…extreme physical hardship and material privation.” And the heroine of the story was the marvelous Lucie Dreyfus, Leonore to his Florestan. Her devotion to her husband was total, her work on his behalf unflagging. “It is for you alone that today I resist,” he wrote to her, “it is for you alone, my darling, that I withstand this long martyrdom.”

While Dreyfus suffered on his distant island, the events that transformed an obscure injustice into the world-famous Affair were slowly unfolding in Paris. In March 1896 the army intelligence service was brought a new piece of evidence from the German embassy: a petit bleu, the name for messages written on small pieces of blue paper and sent around Paris by a system of pneumatic tubes. This one, written but apparently never sent, was from Schwartzkoppen to a French army officer, Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy, and it made it clear that Esterhazy was spying for him.

Advertisement

When Dreyfus was convicted, the intelligence service was headed by Lieutenant Colonel Jean Sandherr, who persisted in the imposture until he was incapacitated by tertiary syphilis. He was replaced by Picquart, who had earlier apologized to an officer on the General Staff for “giving him a Jew” when he assigned Dreyfus to him, but if Picquart’s prejudice didn’t distinguish him from many other officers, his sense of duty and honor did. At first he thought there must have been two highly placed spies in the army, until he realized that Esterhazy was the only one and that Dreyfus had been falsely convicted. But when he brought this evidence to Generals Raoul de Boisdeffre and Arthur Gonse, they ordered him to keep the two cases separate. Whatever happened to Esterhazy, the truth about Dreyfus must be suppressed for the honor of the army.

In September 1896 L’Éclair, a Paris paper hostile to Dreyfus, demanded to know the evidence on which he had been convicted, while revealing that crucial evidence had been kept from his lawyers. The wretched Henry responded by fabricating more incriminating evidence. A farmer’s son who had risen through the ranks, Henry was eager to please his aristocratic superiors, but when he proudly showed his handiwork to Boisdeffre and Gonse, they realized their case was unraveling. Worried that Picquart might keep digging for the truth, they eventually posted him to Tunisia, although he astutely gave a number of documents to his lawyer.

Two months later, in November, Bernard Lazare published a pamphlet, “A Judicial Error: The Truth About the Dreyfus Affair,” which was distributed to every member of the Chamber of Deputies as well as leading journalists. What Lazare didn’t know was the identity of the real culprit. Esterhazy was a decayed aristocrat distantly related to the great Hungarian family. With his enormous mustache and foppish manner, he might have been absurd had he not been so sinister. A spendthrift perennially short of money, he had a clear motive for selling his services to the Germans, and the evidence against him was now so clear-cut that it shouldn’t have taken Maigret to nail him. Instead he remained at liberty, while Henry and Du Paty de Clam repeatedly assured him that he had no need to worry. Finally, in January 1898, Esterhazy was court-martialed in what was even more of a travesty than Dreyfus’s trial. After a perfunctory hearing, the judges took three minutes to acquit him. And so, Samuels writes, the army “had not only condemned a man it knew to be innocent but had absolved a man it knew to be a spy.”

But it was too late, as more and more people were persuaded of Dreyfus’s innocence. One was Auguste Scheurer-Kestner, the vice-president of the Senate, who took the case to the French president, Félix Faure. Another was Léon Blum, who would later be leader of the Socialist Party, prime minister, and then a foe of the Vichy regime, but at this time had barely begun his first careers as a lawyer and a literary critic. He had paid little attention to the case before Lucien Herr, the librarian of his alma mater, the École Normale Supérieure, came to see him in the summer of 1897 and said, “Did you know that Dreyfus is innocent?” Blum was astonished—and transformed. In his book Souvenirs sur l’Affaire (Memories of the Affair, 1935), he wrote, “The Affair was a human crisis, less drawn out and less prolonged but just as violent as the French Revolution and the Great War.”

That seems hyperbolic, but the case was turning into a great Kulturkampf. For one side, hostility to Dreyfus was an epitome of larger positions—conservative Catholicism and antirepublican authoritarianism—while on the other side, as Samuels says, “advocacy on behalf of Dreyfus became a way of registering support for the liberal democratic republic.” Other converts joined the cause, from Georges Clemenceau, who later led France to victory in World War I and who now campaigned for Dreyfus in his paper, L’Aurore, to the Socialist leader Jean Jaurès. Jaurès at first ignored the case on the grounds, all too common on the left, that the working-class movement needn’t concern itself with the fate of a rich officer, but he now grasped the truth.

On January 13, 1898, newsboys across Paris shouted “J’Accuse!” as they sold 300,000 copies of L’Aurore. Its front page was Émile Zola’s “Letter to the President of the Republic,” which read, “I accuse Lieutenant Colonel du Paty de Clam of being the diabolical creator of this miscarriage of justice.” Then, over and over again, “I accuse…I accuse,” until:

finally, I accuse the first court-martial of violating the law by convicting the accused on the basis of a document that was kept secret, and I accuse the second court-martial of covering up this illegality, on orders, thus committing the judicial crime of knowingly acquitting a guilty man.

When Dreyfus was being interrogated, he said, “My only crime is being born a Jew,” and the mob at his degradation had screamed “Death to Judas!” and “Down with the Jews!” This seemed all the more shocking in France, the first country in Europe to emancipate the Jews. In 1791 full French citizenship was granted to Jewish men, and over the next century French Jews, barely a fifth of one percent of the population, enjoyed remarkable success, from great financial families such as the Rothschilds and the Pereires to the hugely popular opera composer Fromental Halévy.

In their modest way the Dreyfus family had shared in this success. Alfred’s great-grandfather was a kosher butcher, his grandfather was a peddler as well as a mohel (ritual circumciser), and his father Raphaël began life peddling, then worked as a commission agent for a Mulhouse firm, and finally opened his own mill. By the time of his death in 1893 he was worth a fortune of 800,000 francs. And at a time when Jewish officers were almost unknown in the British and Prussian armies, hundreds of Jews had served as officers in the French army: under the Second Empire and Third Republic at least twenty became generals. As Samuels writes, Alfred Dreyfus was born into a country whose Jews appeared to be “the best integrated in the world.”

But this success had provoked a brutal reaction, as the old religious Jew-contempt was succeeded by a new racial Judeophobia, or antisemitism, a word that emerged in Germany in the 1860s and passed into every European language. In France its leading exponent was Édouard Drumont, whose horrible but widely read book La France juive (Jewish France), published in 1886, claimed that “the Jew alone profited from the French Revolution” and was adorned with charts and lists of Jewish parasites. Drumont launched the antisemitic newspaper La Libre Parole in 1892, and its circulation reached 200,000.

Nothing was more repellent than the involvement of the Roman Catholic Church. In his strange and haunting proto-Zionist tract Rom und Jerusalem (1862), the German Jewish philosopher Moses Hess had written that “ever since Innocent III…Rome was an unconquerable source of poison for the Jews,” and there was poison enough coming from the pages of La Croix, published by the French Assumptionist order: “Jewry…has rotted out everything…it is a horrid cancer…the Jews are vampires…leading France into slavery.” But casual prejudice could be found even among those who took up Dreyfus’s cause. In his 1891 novel L’Argent (Money), Zola had described the Paris Bourse as “a whole filthy Jewish quarter,” one example among many of the way French—as well as English and American—literature of that age reflected instinctive disdain for Jews.

One might suppose that Zola’s great philippic would arouse sympathy for a Jewish victim. The exact opposite happened. For several months in 1898 France was convulsed by a spasm of antisemitic hatred.1 In Paris posters called for a mass demonstration against “the organizers of treason, the accomplices of cosmopolitan Jewry,” and a mob led by Catholic students chanted “Out with Zola! Death to the Jews!” Soon there were riots in Grenoble, Lyon, and Nancy, where a synagogue was surrounded, and in Rennes, where a mob attacked the houses of Jewish professors. The worst violence was in Algeria, directed against the 30,000 Jews, a minority within the minority of white settlers. Synagogues were ransacked, Zola was burned in effigy, Jews were beaten in the streets, and several were killed.

In the autumn this mass hysteria and violence stopped almost as suddenly as it had begun, but not before Zola had been sued for libel. In August Henry confessed his forgeries to a senior officer and was sent to prison, where he cut his throat. At the very beginning of his career as a protofascist and antisemite, Charles Maurras wrote an elegy to Henry as a “man of honor” who had written a “patriotic forgery,” and a subscription raised a large sum for his widow.

Repeated attempts were made to reopen the case before February 1899, when Faure died suddenly (while enjoying the intimate caresses of his mistress, French political legend had it) and was succeeded as president by the Dreyfusard Émile Loubet. That June the Court of Appeals quashed the first verdict on Dreyfus, and a new court-martial was ordered, raising hopes across the world: “A shif aroysgeshikt tsu breyngen Dreyfus” (A ship sent to bring Dreyfus) was the exultant headline in the New York Yiddish daily Forverts. On his return Dreyfus learned that his new court-martial in August would be in Rennes, a center of Catholic reaction.

As if the new court-martial weren’t dramatic enough, Dreyfus’s brilliant young lawyer Fernand Labori was shot in the back while walking to the court but survived. On September 9 Dreyfus was again found guilty, against all possible evidence, but with “extenuating circumstances.” Ten days later Loubet granted Dreyfus a pardon. Some of his supporters thought he shouldn’t accept it, since it implicitly accepted his guilt, but they hadn’t spent four years on Devil’s Island. It wasn’t until 1906 that the Supreme Court of Appeals overturned the Rennes verdict and completely exonerated Dreyfus. He was reinstated to the army and, near the same courtyard where he had once experienced such horror, was made a chevalier of the Légion d’honneur.

Any idea that the Dreyfus Affair was closed for good was illusory: its repercussions were felt long after—maybe even until today. Someone who doesn’t come out well in Samuels’s account is Hannah Arendt. Her criticism of French Jews for their passivity and for abandoning their identity, or even seeking “to assimilate by adopting [their] own brand of antisemitism” by imitating the higher classes, was thoroughly misplaced, and her claim that the Affair “gave birth to the Zionist movement” was simplistic, even wrong.

It’s true that Herzl said, “What made me a Zionist was the Dreyfus trial.” In 1896, the year after the degradation, he published Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State), and in 1897 he organized the first Zionist Congress in Basel. And yet Herzl was a luftmensch (who but a luftmensch would have dreamed his audacious dream?) and not always reliable. In what he actually wrote at the time of the trial for the Neue Freie Presse, the Viennese newspaper he worked for, he appeared to assume that Dreyfus was guilty and didn’t mention antisemitism. There were already reasons enough for Herzl’s concern. France saw only part of the tide of antisemitism throughout Europe, not least in Herzl’s native Budapest and in Vienna, where the Christian Socialist Karl Lueger was four times elected mayor on an antisemitic platform and four times vetoed by Franz Joseph, until he won again and the emperor relented.

Not that Herzl’s project was welcomed by all Jews. In France as in other Western countries, many of them wished to be accepted as a tolerated and emancipated minority, like Roman Catholics in England and Protestants in France. Judaism was for them a religion, not a nationality: they were Frenchmen or women “of the Mosaic persuasion”—a persuasion not necessarily held with any ardent conviction. That was certainly true of Alfred Dreyfus, who would say Kaddish for his mother and, during his imprisonment, take packets of pork fat out of his meager rations and throw them in the sea, but who was at heart a skeptic and a rationalist whose writings never mention Judaism or the Almighty.

“Who has not read about the sad case of Captain Dreyfus?… What Jew is not concerned with his plight?” read the poster for one of many Yiddish plays about the Affair seen by packed immigrant audiences in New York and Chicago. The Affair inspired a vast literature, from plays to polemics to trashy novelettes to stories like Sholem Aleichem’s “Dreyfus in Kasrilevke” (1902), which gently mocks the way the people of a Ukrainian shtetl were obsessed with the case. A recent example is Robert Harris’s excellent novel An Officer and a Spy (2013) and the French film based on it, J’Accuse (2019).

As Samuels observes, different Jews “all found in the Dreyfus Affair confirmation of their answers to the ‘Jewish Question.’” Socialists thought it showed the need for the Jewish left to organize, while Zionists were stimulated by that rage of Jew-hatred to pursue their dream of a homeland of their own. Those whom Samuels calls the integrationists not only could point to the final outcome of the Affair as a vindication of French republican justice; many of them also believed that it was Zionism that endangered their position, by implicitly accepting the antisemites’ case that Jews didn’t belong in the countries where they lived.

One notable family was divided by the Affair: Marcel Proust was a Dreyfusard, as was his Jewish mother, while his gentile father was anti-Dreyfusard. As Samuels says, the Affair echoes through much of À la recherche du temps perdu, but he might have quoted one passage in which the monstrous Baron de Charlus tells the narrator, apropos Bloch, that it’s a good idea to have a few foreigners among one’s friends. When told that Bloch is French, Charlus replies, “I took him to be a Jew.” He goes on still more sarcastically to say that Dreyfus’s supposed crime is nonexistent: “He might have committed a crime if he had betrayed Judea, but what has he to do with France?… Your Dreyfus might rather be convicted of a breach of the laws of hospitality.” That was exactly what many Jews dreaded: as Karl Kraus said in his anti-Zionist polemic Eine Krone für Zion (A Crown for Zion, 1898), Zionists seemed to think that the European Jews were no more than visitors.

After the drama, the participants dispersed. Dreyfus retired from the army but rejoined during the Great War. His son Pierre won the Croix de Guerre serving on the Western Front, where his nephew Émile was killed. For a time Esterhazy arrogantly went about in society: in March 1898 Oscar Wilde, exiled in Paris, wrote, “I was dragged out to meet Esterhazy at dinner.” But he soon shaved off his mustache, changed his name to Jean de Voilemont, and left for exile in England, where he spent the rest of his life.

In 1935 Dreyfus died, aged seventy-five. The following year Blum became prime minister, having recently been beaten almost to death by fascist louts in Paris, and was denounced to his face in the Chamber by a deputy who said that “for the first time this old Gallo-Roman country will be governed…by a Jew.” Four years later the Vichy regime passed its own antisemitic laws, and around 75,000 Jews, a quarter of the total, were deported to the east to be murdered.2 Some of the large Dreyfus family escaped to America, but Lucie remained in France and sheltered in a convent, whose nuns may or may not have known her identity. She died shortly after the end of the war of natural causes, unlike Madeleine Lévy, Alfred’s favorite granddaughter. She was arrested in 1943 and sent to the notorious Drancy camp north of Paris, and thence to Auschwitz, where she was selected for labor and died of typhus in 1944.

“I have the solution of the Jewish Question,” Herzl wrote exultantly in his diary as he began to write The Jewish State. The Dreyfus Affair was a crucial part of that “question,” and the state Herzl dreamed of became a reality. Whether it finally answered that question is another matter.

This Issue

April 18, 2024

The Corruption Playbook

Ufologists, Unite!

Human Resources

-

1

See Pierre Birnbaum, The Anti-Semitic Moment: A Tour of France in 1898 (Hill and Wang, 2002) reviewed in these pages by Julian Barnes, April 10, 2003. ↩

-

2

See my review of Julian Jackson, France on Trial: The Case of Marshal Pétain (Harvard University Press, 2023), in these pages, December 7, 2023. ↩