More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

Advertisement

More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

Geoffrey Wheatcroft’s books include The Controversy of Zion, Yo, Blair!, Churchill’s Shadow, and Bloody Panico! or, Whatever Happened to the Tory Party?, which was published in May. (August 2024)

The Unwilling Celebrity

Maurice Samuels’s Alfred Dreyfus is a biography of the very private man at the center of one of the greatest public controversies of modern times.

Alfred Dreyfus: The Man at the Center of the Affair

by Maurice Samuels

April 18, 2024 issue

The Collaborator in Chief

The trial of Marshal Philippe Pétain was also implicitly a trial of the millions of French men and women who may have disliked the German occupation but who compromised with it and obeyed Vichy.

France on Trial: The Case of Marshal Pétain

by Julian Jackson

December 7, 2023 issue

Bloody Panico

The British Conservative Party was once one of the great popular political movements of Europe. What happened?

Tory Nation: How One Party Took Over

by Samuel Earle

Boris Johnson: The Rise and Fall of a Troublemaker at Number 10

by Andrew Gimson

Pandemic Diaries: The Inside Story of Britain’s Battle Against Covid

by Matt Hancock with Isabel Oakeshott

The Fall of Boris Johnson: The Full Story

by Sebastian Payne

Out of the Blue: The Inside Story of the Unexpected Rise and Rapid Fall of Liz Truss

by Harry Cole and James Heale

The Reign: Life in Elizabeth’s Britain, Part 1: The Way It Was, 1952–79

by Matthew Engel

The Worm in the Apple: A History of the Conservative Party and Europe from Churchill to Cameron

by Christopher Tugendhat

March 23, 2023 issue

The Limits of Press Power

To what extent did newspapers influence public opinion in the US and Britain before and during World War II?

The Newspaper Axis: Six Press Barons Who Enabled Hitler

by Kathryn S. Olmsted

The Media Offensive: How the Press and Public Opinion Shaped Allied Strategy During World War II

by Alexander G. Lovelace

November 3, 2022 issue

An Unexpectedly Modern Monarch

Despite his mundane outlook and stiff conventionality, George V may have ensured the survival of the British monarchy in a turbulent century.

George V: Never a Dull Moment

by Jane Ridley

April 7, 2022 issue

Mogul of Mystery

Robert Maxwell's improbable transformation from yeshiva boy to British media baron and outrageous swindler.

Fall: The Mysterious Life and Death of Robert Maxwell, Britain’s Most Notorious Media Baron

by John Preston

October 7, 2021 issue

Europe’s Most Terrible Years

For Germans, World War II began with deceit and cruelty and ended in physical and moral desolation.

Poland 1939: The Outbreak of World War II

by Roger Moorhouse

“Promise Me You’ll Shoot Yourself”: The Mass Suicide of Ordinary Germans in 1945

by Florian Huber, translated from the German by Imogen Taylor

December 17, 2020 issue

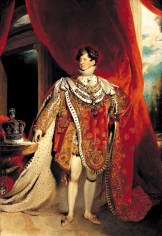

A Discriminating Dissolute

George IV: Art and Spectacle

an exhibition at the Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, London, November 15, 2019–May 3, 2020; and the Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh, October 16, 2020–April 5, 2021

George IV: King in Waiting

by Stella Tillyard

May 28, 2020 issue

‘Feasting with Panthers’

The Happy Prince

a film written and directed by Rupert Everett

Oscar: A Life

by Matthew Sturgis

March 21, 2019 issue

One Hundred Years of Destruction

To have seen devastating bombing as the only way through was forgivable in the dire circumstances of 1940, but by the beginning of 1942 defeat was no longer feared.

RAF: The Birth of the World’s First Air Force

by Richard Overy

Aerial Warfare: The Battle for the Skies

by Frank Ledwidg

December 20, 2018 issue

A Star Is Born

Churchill

a film directed by Jonathan Teplitzky

Darkest Hour

a film directed by Joe Wright

January 18, 2018 issue

Subscribe and save 50%!

Read the latest issue as soon as it’s available, and browse our rich archives. You'll have immediate subscriber-only access to over 1,200 issues and 25,000 articles published since 1963.

Subscribe now