When Thomas Bernhard died, in 1989, he left a will forbidding any publication or performance of his work in his native Austria. The will, like so many of Bernhard’s writings before it, provoked a huge controversy among his countrymen, confirming the novelist and playwright as a brilliant stage manager of his own legend. No deathbed reconciliation could have ensured the Austrians’ attention as lastingly as this parting slap, which made immortal the feud that he had always carried on with his country.

The episode of Bernhard’s will offered one last reprise of his career’s major theme, which is the paradoxical fate of the satirist, the provocateur, and the nihilist in the modern world. From Leopardi to Dostoevsky to Nietzsche to Beckett—and Bernhard arguably belongs in this tradition—it is precisely the writers who condemn the world most violently whom the world likes to honor most. Yet the very closeness of the embrace in which they are enveloped serves, as in a boxing match, to make further blows impossible. Almost inevitably, their furious challenge is turned into just another literary trope.

Just so, the more ferociously Bernhard blasphemed against Austria, the more he became the one indispensable Austrian writer. By the end of his life, Bernhard’s plays, conceived as frontal attacks on the Austrian theater establishment and playgoing public, were being staged at Vienna’s storied Burgtheater. He was like a rich man who tries to throw his fortune away, only to find all his waste transformed into windfalls. And so, inevitably, the suspicion intrudes that he was really just another canny investor of his fame all along. As Gitta Honegger points out in her biographical study Thomas Bernhard: The Making of an Austrian, by now “Austria has officially reclaimed its nasty problem child as a national treasure alongside that other ungrateful son of Salzburg, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.”1

For this reason, My Prizes, a newly translated book that Bernhard wrote in 1980, is more significant than its slender size and premise might suggest. The volume is made up of short memoirs, each devoted to a different literary prize Bernhard received; and almost all of them culminate in some extravagant act of sabotage or self-sabotage. Take, for example, the occasion in 1971 when Bernhard was given the Grillparzer Prize, one of Austria’s most prestigious literary awards, whose previous recipients included Gerhart Hauptmann, Franz Werfel, and Friedrich Dürrenmatt. It was the hundredth anniversary of the death of the Austrian playwright and poet Franz Grillparzer, and as Bernhard wrote in his description of the occasion in Wittgenstein’s Nephew:

To be singled out for the award…on the hundredth anniversary of the poet’s death seemed to me a signal distinction. I’m now being honored by the Austrians, I thought, by my fellow countrymen, who up to now have done nothing but kick me…. That the Austrians, having previously scorned or ignored me, should be giving me their highest award struck me as a kind of overdue compensation.

Yet when he arrived at the Grillparzer Prize ceremony, he went literally unrecognized: “I walked up and down the entrance hall of the Academy several times with my aunt, but nobody took even the slightest notice of us.” So Bernhard and the woman he calls his aunt—actually his life partner, Hedwig Stavianicek, who was thirty-seven years his senior—decided to simply seat themselves in the middle of the auditorium. Eventually, after much commotion on the dais, someone recognized him in “the tenth or eleventh row,” and a functionary came to tell him to move up to the first row.

But Bernard was not so easily placated: “Naturally I will only go into the first row if President Hunger has requested me personally to do so, it goes without saying only if President Hunger is inviting me personally to do so.” At last, the president of the Academy inched down the crowded row to make a personal plea. When he finally received the award, Bernhard was chagrined to learn that it had no money attached. To add insult to injury, the award certificate was “of a tastelessness, like every other award certificate I have ever received, that was beyond comparison.”

That sentence, with its self-canceling hyperbole—Bernhard says the certificate is beyond comparison, even while comparing it to other certificates—poses in miniature the question raised by My Prizes, and indeed by Bernhard’s work as a whole. Are we supposed to laugh at Bernhard’s histrionics, his exaggerations, his choleric attitudinizing? Or is all this meant quite sincerely, as Bernhard’s appropriate reaction to a country, and a universe, he finds abysmal and absurd? Did Bernhard act unreasonably in refusing to make himself known at the Grillparzer Prize ceremony, or does the blame lie with the Austrian cultural establishment, as he suggests: “I’m not going to go and meet them, I thought, just as (in the deepest sense of the word) they didn’t meet me”?

Advertisement

Reading My Prizes, the suspicion grows that Bernhard must have been secretly thrilled when he went ungreeted at the ceremony. It spared him the necessity of contriving to be rebuffed, as he famously did at the Austrian State Prize ceremony in 1967. This is the subject of the best piece in the book, thanks to the comic slow burn of Bernhard’s resentment at being awarded only the “small” prize—given for a single book, usually to young writers—rather than the “large” prize, given for a writer’s whole body of work. “What possibly had really been dreamed up by idiots as an honor, to me, the more I thought about it, was a despicable act,” he fumes, “a beheading would be putting it too strongly but even today I feel the best description of it is a despicable act.” Actually, he’s no more enthusiastic about the large prize: “When people asked me who had already won this so-called Big State Prize” (one of Bernhard’s favorite techniques is to add a skeptical “so-called” to perfectly ordinary words),

I always said, All Assholes…what’s more they’re Catholic and National Socialist assholes plus the occasional Jew for window dressing…. It’s a collection of the biggest washouts and bastards.

Financial need compelled him to accept the prize, Bernhard says, but he took his revenge when he gave his acceptance speech. “I hadn’t got to the end of my text before the audience became restive,” he writes with mock naiveté, “I had no idea why, for my text was being spoken quietly by me and the theme was a philosophical one, profound even, I felt, and I had uttered the word State several times.” Since My Prizes includes the text of the speech as an appendix, we’re able to see just how Bernhard referred to the Austrian state: as

a perpetual national prison in which the elements of stupidity and thoughtlessness have become a daily need. The state is a construct eternally on the verge of foundering, the people one that is endlessly condemned to infamy and feeblemindedness, life a state of hopelessness in every philosophy and which will end in universal madness.

Surely he would have been disappointed if the minister of culture had failed to respond as he did—that is, by storming out of the auditorium while cursing Bernhard. To be misunderstood and alienated—a solitary, unappeasable, possibly mad genius—was the essence of Bernhard’s self-conception, as it is the essence of every major character in his fiction. Roithamer, the mad scientist of Correction, who spends his family’s fortune to build an uninhabitable building he calls the Cone, is “reprimanded on all sides for having had such an idea at all in a time opposed to such ideas, a time predisposed against such ideas and their realization.”

The mad prince in Gargoyles, who immures himself in his ancestral estate, thinks the same way:

The prince said he was forever compelled to make a stupid society realize it was stupid, and that he was always doing everything in his power to prove to this stupid society how stupid it was. But sometimes this stupid society would say that he was stupid.

Konrad, in The Lime Works, has “eleven or twelve previous convictions for so-called libel in this country,” because “strictly speaking, you might say that everything he could say about this weird country…could be considered a so-called libel.”

Certainly, everything Bernhard had to say about Austria strove to be actionable. In Concrete, to take just one example, it is

a country whose absolute futility utterly depresses me every single day, whose imbecilities daily threaten to stifle me, and whose idiocies will sooner or later be the end of me, even without my illnesses…. Whose indifference to the intellect has long since ceased to cause the likes of me to despair, but if I am to be truthful only to vomit.

The Austrian countryside, in Bernhard, is like the South in Deliverance—an ignorant, violent backwater plagued by disease, suicide, and sexual abuse. The unspeakable Joseph Fritzl case, in 2008—in which an Austrian man was found to have imprisoned his daughter in his basement for twenty-four years, forcing her to bear seven of his children—must have struck any reader of Bernhard as horribly familiar: incest and imprisonment figure in many of his novels.

About the capital he can be kinder, but only occasionally. In Prose, a collection of seven stories published in 1967 and now translated into English for the first time, Bernhard describes Vienna as

Advertisement

the most dreadful of all old cities of Europe. Vienna is such an old and lifeless city, is such a cemetery, left alone and abandoned by all of Europe and all of the world…what a vast cemetery of crumbling and premodern curiosities!

Prose does not add much to our sense of Bernhard’s achievement, except by confirming that the novel, not the short story, was his ideal genre. Writing stories, Bernhard had a weakness for dramatic, last-minute revelations, to make the trap of the narrative spring shut.

In “Two Tutors,” for instance, we learn on the last page that the narrator, who has been describing his pathological insomnia, was fired from his last job as a tutor after he shot something from his bedroom window in the middle of the night. He says it was an animal, but his somber, evasive musings—“I heard my name called. A good shot. Naturally, I instantly handed in my resignation”—leave the reader wondering if it wasn’t actually a pupil he killed. What seems uncharacteristic about this is not the grotesquerie or the violence—both of which are Bernhard’s stock-in-trade—but the attempt to create a Poe-like dread. In his novels, by contrast, the madness and guilt of his narrators are not sprung on the reader at the end: they are front-and-center from the beginning, and so lose any glamour. (We learn that Konrad has killed his wife on the second page of The Lime Works.)

The abuse of Vienna, however, shows that as early as Prose, Bernhard already cherished his contempt for Austrian culture. He can never forget that Vienna, once the capital of a vast multinational empire, is now a stage set of vanished grandeur, the swollen head on the shrunken body of the Austrian Republic. The contrast between the city’s pretensions and its reality is a standing offense to Bernhard: “In Vienna today art is nothing but a sickening farce, music a worn-out barrel organ, and literature a nightmare.”

Ironically, in this fierce desire to shatter the Austrian cult of culture, Bernhard is very much the heir of earlier generations of Austro-Hungarian intellectuals. Already in 1908, in his modernist manifesto “Ornament and Crime,” Adolf Loos complained about the Austrian preference for frivolous decoration: “The ornamental epidemic is state-approved and subsidized with public funds.” Loos even sounds rather like Bernhard when he writes feverishly about “the arduous, spoiled sickness of the modern ornament. No one living on our level of culture can create ornament any more.” The austerity Loos prefers—“Soon the streets of cities will glisten like white walls”—is exactly the aesthetic Bernhard associates with exigent genius: Roithamer’s Cone declares its greatness in its geometric purity of line.

One glaring example of hypocritical Austrian ornamentation, writes Gitta Honegger, could be found at Steinhof, the architecturally exquisite insane asylum in Vienna. Famous for its Art Nouveau church designed by Otto Wagner, Steinhof’s rooms featured

bars…discreetly set into the windowpanes to give the impression of wrought-iron ornamental grillwork. Everything was arranged to simulate the continuation of exclusive sophisticated leisure.

Bernhard may have had those iron bars at the back of his mind when he had Konrad, in The Lime Works, announce:

I ripped out the ornamental ironwork and installed functional iron bars…those thick walls and the iron bars sunk into them instantly show that this is a prison.

Steinhof is a recurring, darkly emblematic presence in Bernhard’s work. Most famously, in Wittgenstein’s Nephew, Bernhard writes about his stay in a pulmonary hospital adjacent to Steinhof, where his friend Paul Wittgenstein was being treated for mental illness. In Bernhard’s telling, his own lung disease—which he contracted as a teenager, and which almost killed him on several occasions—was not essentially different from Wittgenstein’s insanity. Both were prices paid for the intensity, the megalomania, that for Bernhard is the essence of an authentic existence:

I had behaved toward myself and everything else with the same unnatural ruthlessness that one day destroyed Paul and will one day destroy me…. Paul never controlled his madness, but I have always controlled mine—which possibly means that my madness is in fact much madder than Paul’s.

The pairing of Paul Wittgenstein—relative of the great philosopher, scion of the same wealthy family, and a legendary bon vivant and eccentric—and Thomas Bernhard—an illegitimate child raised in poverty and misery, as he recorded in his memoir Gathering Evidence—is thus not as surprising as it may seem. In the most moving scene of Wittgenstein’s Nephew, they are shown to be soul-companions because they share the ability to confront ultimate reality, which is terrible and maddening. When they meet halfway between their two hospitals, they are like a real-life Hamm and Clov:

Grotesque, grotesque! he said, and began to weep uncontrollably. For a long time his whole body was convulsed with weeping…. We could have met again, but we never did, because we did not want to expose ourselves to a strain that was almost unendurable.

This vision of the world’s absurdity, futility, and evil is a constant in Bernhard’s work. What varies is the mood or spirit in which the vision is enforced. In the earlier books, there is little intentional comedy: in fact, Bernhard is often an extremely self-serious writer, with something of the dull earnestness of the autodidact. The world is meaningless, he writes again and again:

No doctrine holds water any longer; everything that is said and preached is destined to become ludicrous. It doesn’t even call for my scorn any longer. It doesn’t call for anything, anything at all.

The one thing that escapes being ludicrous, at least partially, is the dedicated artist, whom Bernhard loves to portray as both heroic and hideous. In The Loser, Bernhard writes in the first person about his (invented) friendship with Glenn Gould, turning Gould into yet another demonstration of the artist’s implacable will. When he is practicing the piano, Gould notices an ash tree in front of the house, and it distracts him; rather than draw the curtains, he goes outside and chops down the tree:

If something is in our way we have to get rid of it, Glenn said, even if it’s only an ash. And we don’t even have the right to ask first if we are allowed to chop down the ash, we weaken ourselves that way.

This Nietzscheanism is part of what makes Bernhard seem rather anachronistic in his modernism. By 1983, when The Loser was published, few writers were still so enthralled by the cult of the artist-titan. Nor do we now place such fascinated faith in madness. There is a suggestive contrast to be made between Wittgenstein’s Nephew and Robert Lowell’s Life Studies, with its far more realistic and pitiable portrait of the mentally ill writer. The mid- and late twentieth century, in America, was an age of therapy; while to Bernhard, who cannot accept the reduction of existential terror to neurosis, therapy is another on the long list of modern abominations. “Of all medical practitioners, psychiatrists are the most incompetent, having a closer affinity to the sex killer than to their science,” he writes. “Psychiatrists are the real demons of our age, going about their business with impunity and constrained by neither law nor conscience.”

Is it wrong to find such a passage funny? Or is Bernhard canny and self-skeptical enough to understand the impression that his hyperbole is making, and to connive at it? In the case of psychiatrists, Bernhard’s lifelong hatred and fear of doctors make it hard to tell if he is exaggerating, or how much. But surely he is conscious that his attack on dog owners, in Concrete, sounds manically excessive:

People love animals because they are incapable even of loving themselves. Those with the very basest of souls keep dogs, allowing themselves to be tyrannized and finally ruined by their dogs…. It isn’t as absurd as it may first appear when I say that the world owes its most terrible wars to its rulers’ love of animals. It’s all documented, and one ought to be clear about it at once. Those people—politicians, dictators—are ruled by a dog…. They love a dog and foment a world war in which, because of this one dog, millions of people are killed.

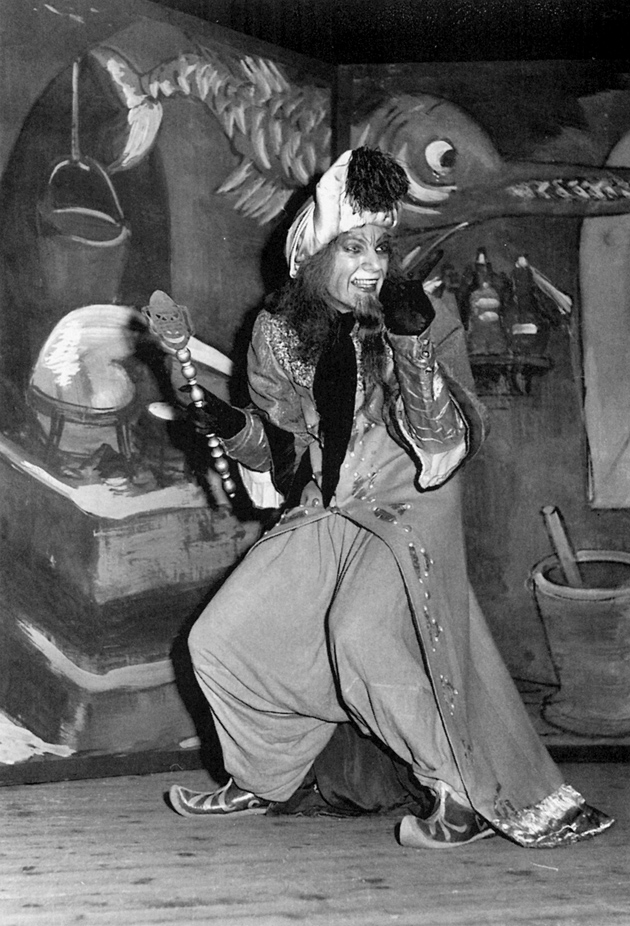

This starts out plausibly, but it ends up as black comedy. And in fact, the quotient of deliberate comedy in Bernhard’s writing seemed to increase steadily throughout his life. The production of his 1986 play Ritter, Dene, Voss, which came briefly to New York this past fall, was at its best when energized by Bernhard’s comic extremism. It offers yet another version of Bernhard’s standard plot: this time, two sisters in a wealthy Vienna family, both actresses, welcome home their mad philosopher brother from Steinhof.

The brother, Ludwig, is obviously a hybrid of Ludwig and Paul Wittgenstein. Like the former, he has spent time in England and Scandinavia, and writes incomprehensibly brilliant works; like the latter, he has made Steinhof his true home, and his jibes about the greed of the doctors and attendants echo remarks in Wittgenstein’s Nephew. All of Bernhard’s favorite themes are here: the suffocation of family life, the corruption of Austria’s cultural institutions, the identity of genius and madness. Yet in staging a conflict he has often written about, Bernhard emphasizes its farcical elements: when one sister offers Ludwig cream puffs, saying that they are his favorite dessert, he crams them into his mouth and sprays them across the table.

Bernhard’s willingness to see Ludwig as a comic figure, as well as a tragic one, is suggestive of the way his later work evolved. Konrad, in The Lime Works (1970), never writes his magnum opus; he ends up killing his wife instead. Rudolf, in Concrete (1982), also never writes his magnum opus—an essay on Mendelssohn—but his madness takes the ludicrous form of travel mania:

I’ve never succeeded anywhere—in Sicily, on Lake Garda, in Warsaw, in Lisbon or in Mondsee. In all these places and many others I’d repeatedly tried to start work on Mendelssohn Bartholdy; I’d gone to these places for this purpose only and stayed as long as possible, but always in vain.

In My Prizes, Bernhard says explicitly what could easily be deduced from his books, that he too suffered from this kind of restlessness. Bernhard’s characters are always in quest of the perfect house in which to write, and regularly ruin their own lives and the lives of others in the process. But the obsessiveness on display in My Prizes is essentially comic, because the only thing at stake is Bernhard’s prize money. When he gets the Julius Campe Prize, he immediately blows the whole five thousand marks on a sports car, a white Triumph Herald with red leather interior:

Yes, said the salesman, he would arrange for a similar car to be delivered for me in the next few days. No, I said, not in the next few days, now, I said, right away. I said right away the way I’ve always said it, very firmly…. This is the only car I will buy, as is, standing right here.

Even when purchasing a house, with the money from the Bremen Prize as a down payment, Bernhard acts with irrational haste. He insists on buying the first farmhouse he is shown, even though it is totally decrepit, because he is hypnotized by the real estate agent’s description:

The real estate agent kept saying exceptional proportions and the more often he asserted this, the clearer it became to me that he was right, in the end it wasn’t him saying the property had exceptional proportions, it was me saying it, and saying it at every moment.

What makes these anecdotes more than jokes Bernhard tells on himself is the way they enact, and subvert, the very philosophy of life that he expounds quite seriously in his fiction. Bernhard’s impulsive purchases are parodies of fateful decisions, carried out in the same spirit—arbitrary, ruthless, absolute—as any ethical or artistic project must be. The second volume of Bernhard’s autobiography, “The Cellar,” attributes the saving of his whole life to just such a spontaneous, seemingly reckless decision—when, as a teenager, he decided one morning not to go to school, which he despised, but to go to a labor exchange and get a job as a grocer’s apprentice instead.

“Such a moment is crucial for our survival; we simply have to pit ourselves against everything or quite simply cease to exist,” Bernhard writes. If the same kind of obstinacy sometimes leads to buying an unlivable house, or to making a commotion at an award ceremony, that does not mean it is ridiculous. Or perhaps it means that embracing the ridiculous, in himself and in the world, is what enabled Bernhard to tolerate the loneliness he both complained and boasted of:

The language I speak is one which I alone understand, no one else, just as everyone speaks a language which he alone understands. Those who think they understand are either fools or charlatans.

This Issue

February 10, 2011

-

*

Yale University Press, 2001, p. xi; reviewed in these pages by Tim Parks, January 11, 2007. ↩