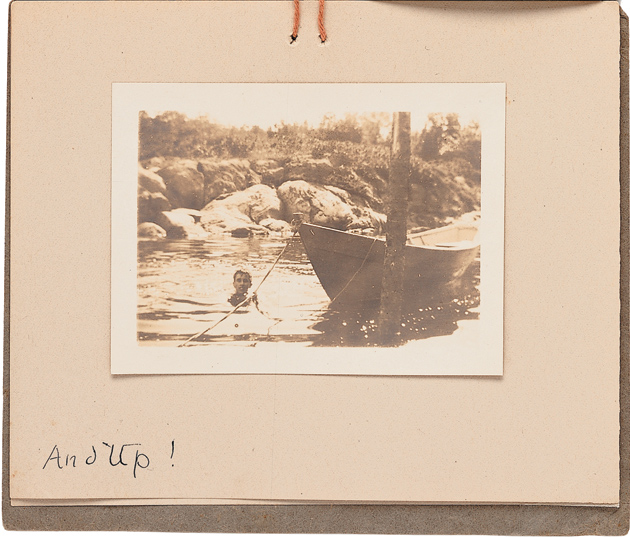

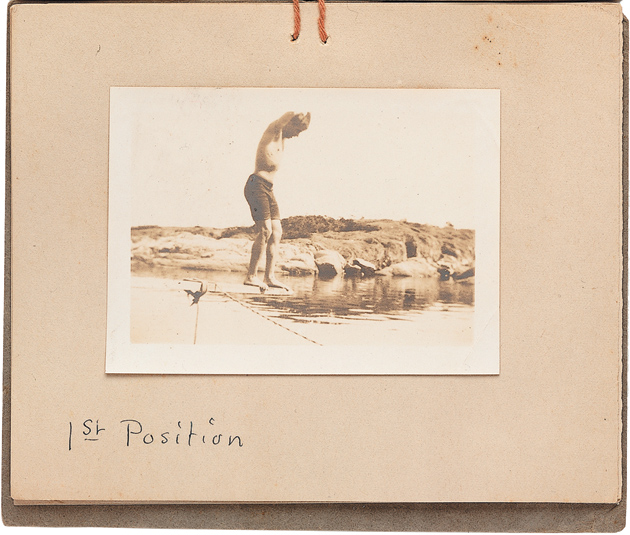

Prints and Photographs Division, the White Collection/Library of Congress

Detail from ‘The Seventh Thousanth and Eighth Hundredth and Sixty Third Performance at the Diving Board L.G.H., 1911,’ an album of snapshots by the photographer F. Holland Day. This photograph and the one on page 58 are from Verna Posever Curtis’s Photographic Memory: The Album in the Age of Photography, which has just been published by Aperture

“Who is that?” Adam asked, pointing at a boy on a swing set. Adam was helping, pasting photographs into an album at the kitchen table. His mother, rolling out a piecrust at the counter, paused to look.

“That’s Uncle Tommy,” she said. “Don’t you get flour on that.”

Next there were some grown-ups sitting on Gramma and Grampa’s couch. Next a lot of people in front of extra-tall corn, kids in front. “Is this Aunt Rosalie?”

“That’s Rosalie all right—look at the hair.”

“Are you there?”

His mother peered over at the snapshot he was studying. “That’s me. The smallest one, over on the end there, with the smocked dress and the pigtails.”

Adam considered the sad-looking little girl. He would have liked to pat the girl’s head, but now she was just a bitsy kernel inside his mother. “Smocked dress. Smocked dress,” he said, stacking the sounds up like the wooden blocks he used to play with. The tallest of the children was blurry. He must have moved. “Who is that boy, at the other end?”

“Let me—oh. That’s Phillip.”

“Phillip?”

“The oldest. Your Uncle Phillip.”

“Oh…” Adam studied the picture and reviewed the jungle of legs he’d clambered about in at the last family occasion, belonging to cousins and aunts and uncles and second cousins and great-aunts and great-uncles. “He was at Gramma and Grampa’s house on Easter?”

“You’ve never met him. He’s far away.”

“Is he older than Uncle Tommy?”

“Yes.”

“Is he older than Uncle Frank?”

“What did I say, Adam? Phillip’s the oldest. Are you going to put that into the album, or are you going to wear it out looking at it?”

Adam bent obediently over his task for a moment. “What was Uncle Phillip like when he was my age?

“I wouldn’t know,” his mother said. “I wasn’t born yet.”

“But…what was he like after you were born?”

She could tell Adam about Uncle Tommy when he was little if he wanted to know, she said, or about Uncle Frank or Aunt Rosalie or Aunt Hazel or Uncle Ray. But given the difference in their ages, she and her brother Phillip might as well have grown up in different households. She rotated the piecrust a severe quarter-turn and bore down on it with the rolling pin. “He went away east to college, and he never came back, except once, when I was twelve, to visit. Daddy—Grandfather Jack—had expected him to take over the farm. Grandfather Jack was heartbroken. He never got over it, even though the rest of us stayed.”

“Oh. Did Grampa Jack yell at Uncle Phillip?”

“Grandfather Jack loved Phillip. We all did. Phillip was the oldest. Phillip was family.”

“Oh. Did he die?”

“Did who die? Of course not. What kind of question is that? He went away to live.”

“Oh.”

Adam kept his trusting gaze trained on his mother, while cautiously attempting, as if he were groping his way along a wall behind him, to locate a door. “Where did Uncle Phillip go away to live?” he said, with cagey nonchalance. “Did he go away to live in Des Moines?”

Betsy frowned at her piecrust, now a near-perfect circle. “If Phillip lived in Des Moines he would come to Easter. And Thanksgiving and Christmas. Phillip went to Europe.”

“Europe?”

“You know what Europe is, Adam. It’s across the ocean. It’s a continent, like America. We’ll look on the globe later.”

“Was Uncle Phillip a nice boy?”

“Nice? Well, generous, I suppose. Impractical.” He’d brought her a present, a sweater from France. But it hadn’t gone with any of her clothes, and she had never worn it.

“What—“ Adam began. His mother swiveled around to him, terrifyingly, but then blinked and turned back to her piecrust. “He never did have his feet on the ground. Grandmother Alice gave that thing away to someone who could use it. I would have outgrown it soon enough, anyway.”

The pie was cooling on the ledge. The photographs were pasted carefully onto heavy pages. Adam wandered off into the newly harvested field and stretched out on his back, staring into the shining blue.

So, he had been waiting and waiting, and finally, one interesting thing had happened in his life—he had discovered a secret person. A person who had just slipped right out of the family pictures. The other boys and girls who got caught by the pictures had been turned into his mother and uncles and aunts, but his new Uncle Phillip was far away, beyond the ocean.

Advertisement

He sat up too quickly and closed his eyes to steady himself. Red suns flared across the darkness, and when he opened his eyes again, there was the combine, tiny, shearing off the billowing gold in the next field. The little toy figure driving was probably Uncle Frank.

Just past the combine was the curve of Adam’s great planet, Earth. It was a known fact that Earth was round and that it was spinning in the middle of the sky.

God had created Earth with its vast oceans, which Adam had seen pictures of, and its blue air. But all that spinning of Earth’s was what created the tides and the winds, and it was what created time, too.

Miss Brewer had explained. Earth was never still. It twirled like a lollipop on a stick, so that you looked at the sun and then you looked at the moon, and that was a day. But the lollipop was also swinging in a great, oval loop, like the rim of a platter, around the sun. It always went back right where it had started, but only when one whole year had been pushed out into space for good.

It made you dizzy to think of. Some people might be awake now on the other side of the planet, walking around in dark, upside-down Australia, and yet they would snap back onto Earth with every step they took, as if their feet were magnets. Because the real situation was, the world had no top or bottom, and he was just as upside-down, right now in broad daylight, as those people in nighttime Australia were.

Miss Brewer had told them that they would never fall off Earth. But what if Miss Brewer was mistaken, and something went wrong? What if one of Earth’s parts got broken, the brakes, for example, and Earth started to spin faster—then would they all go flying off? Would the oceans spill all over the place? Would the continent America bump into the continent Europe? Would day and night just be little strips—light dark light dark?

In fact, the wind was picking up this very instant. That was normal, of course…But oh—there went the stick of gum he was just about to unwrap!

Probably no one else was paying much attention, and he was the first to notice. Should he run inside and tell his mother? She would laugh at him, or say he was lying. And anyway, it was too late to do a thing about it—the blue above him was already deeper, more intense than it had been moments ago…

Adam clung to some bits of stubble and closed his eyes. Hang on, he thought, as Earth gained speed and spun recklessly into night—hang on, hang on, hang on!

The cause of death was given as pneumonia. There was to be a memorial in London for people who had known and loved Phillip, but the funeral was back home, strictly for the nearest of kin, who for decades had seen him only in clippings sent by a vigilant cousin living in California. When he arrived in person, the coffin was, of course, already sealed. In his absence, over time, he had brought a certain amount of honor to the tiny town where he’d grown up, and he had become a source of pride by virtue of being admired elsewhere.

Phillip’s friend Vivian knew a bit about his parents, and she had written to them, urging them with just the right degree of warmth to come over for the memorial. They declined, saying that they were in poor health and couldn’t travel. But it seemed that there was one relative who was planning to attend—some nephew of Phillip’s named Adam, who had written her a brief note to say as much.

Squashed into his seat, streaming through the wonderful clouds for the first time in his life, Adam recalled his childhood attempts to commune telepathically with his mysterious uncle, a hazy figure, radiant and beckoning, who saw the best in him, even when others shook their heads and sighed. Too bad he had never actually dared to write a letter…

Day streamed toward the airplane, the plane glided downward, Adam was fitted into flowing channels of people, a train collected then deposited him—improbable as it was—only a few blocks from his destination in a place called Chalk Farm, though it was actually part of London and not a farm at all. The couple—Indian, Adam conjectured—who ran the peculiar little hotel managed to scare up an iron, and he was able to reconstitute the shirt that his pack had turned into a wad.

Advertisement

And a good thing, too—he hadn’t anticipated the elegance of the occasion, he realized as he ascended the wide front steps of the hall where the memorial was to be held. He hadn’t anticipated anything. It was the end of May. He had just finished college and his girlfriend had just broken up with him as well, erasing quite a lot of his envisioned future. His graduate program wouldn’t start until fall, and the summer job he had rounded up in Cincinnati wasn’t to begin for three weeks. He did not mention the memorial to his parents when he called to tell them he had saved up enough to take a trip. Europe? his mother said, as if she’d never heard the word.

In the lobby, Adam’s language floated softly around him, but refracted through the many accents, it sounded unfamiliar. In fact, the similarity between the exotic beings who had convened here and regular people seemed nominal. So many people, from so many different countries, each of whom looked so distinctive, so interesting, so supremely confident of his or her right to occupy space!

Say thank you, say it again, say excuse me, say please, say it louder, not that loud, say grace, don’t get in the lady’s way, ask for seconds it’s polite, don’t take so much, pay a call, bring a gift, don’t overstay your welcome—no one in his family had ever had that look! No one in his family had ever looked like they had the right to be anywhere at all!

Or perhaps his Uncle Phillip had. Adam parked himself next to a column in the corner of the lobby before going into the auditorium, just to gawk. Yes, it was as though aliens from an advanced civilization had cleverly disguised themselves as humans, in order to effect some purpose that had not yet been revealed to him.

Maybe some sort of practical joke. As he gazed around at the drifting crowd forming and reforming into various configurations, one of the aliens detached herself and headed in his direction. “Hullo, great that you could make it, thanks so much, oh—Vivian,” she said, as he glanced over his shoulder for whomever she might be addressing.

“Vivian.” She pointed to herself. “You are Adam, aren’t you? Did you just get in today? You must be knackered.”

Her hair, a candidly artificial red, was chopped into a rough thatch that stood out, shocked, all around her head, though her small, pointy face seemed distantly concentrated, as though she were counting, trying to keep track of little, rolling objects while she spoke.

So this was Vivian. Was she the practical joke? From the letter she’d written to his grandparents, he’d pictured his uncle’s girlfriend as a very proper sort of lady with several chins, but despite the little lines around her heavily made up, tilted green eyes and a slightly worn quality, she looked like a child dressed up in her mother’s chic suit and stiletto heels. A leggy child. The way she spoke was wonderful to his ears, and she wore a number of great big rings on her delicate, mobile hands.

“What,” she said.

Oh—he had been staring. “How did you recognize me?” he said.

There was a little frill of a laugh. “Well, frankly, darling, it’s like seeing a ghost. An old ghost. I mean, well, not old, obviously; a former—no…a what? A ghost of former times. Though, oh dear, I suppose all ghosts are that by definition, aren’t they. Anyway, come, we’ll do the rounds—people are wanting to meet you.”

Evidently, some of his uncle’s friends actually did want to meet him. Or at least to get a look at one of the relatives. He had been told without enthusiasm by his mother and his grandparents that he looked something like his uncle, but the people to whom Vivian was introducing him seemed to find the resemblance both startling and wonderful. The hair and eyes, several of them said—identical. Well, yes, those things of course—every single person in the family had the same shiny wheat-colored hair and gray eyes, nothing special there…In the blur of murmured condolences, it would not have done, he felt, to mention that he had never in fact encountered his uncle.

A group of people, widening and narrowing gently, like a circlet of waves ringing a small island, surrounded a man of close to, Adam estimated, fifty. Olive skin, black hair, cream-colored suit, eyes as pale as a wolf’s…His bearing was painfully dignified, as if he were encased in a layer of some substance that inhibited his motions—shaking a hand, kissing a cheek…”Simon,” Vivian whispered to Adam.

“Who?” Adam whispered back, leaning in toward her.

She patted his hand. “Simon,” she whispered, a little more loudly.

“Ah!” Adam said. He felt himself flush, and for a moment his heart drummed.

They took seats in the auditorium, and a number of people, including Vivian, got up on the stage, one after another, to talk about his uncle or tell a story. The man named Simon introduced the event in a sentence or two but otherwise did not take part.

When his uncle died, Adam learned, building had already begun on his plans for a large museum gallery, entirely devoted to Asian and Islamic calligraphy, a passion of his. There was also a concert hall under construction that he had ardently wished to see completed. But the project he had cared about most of all had been tabled. An experiment, apparently; very improbable sounding—a cluster of homes, with turf on the roofs, and little windmill-type things, and reflectors to snare sunlight, and outlandish rigging so that water could be reused…interesting, of course, but (Adam realized he had been just about to think his mother’s awful word) “impractical.”

Four or five anecdotes diverted quiet sniffles into loud, grateful laughter. A small, unprepossessing man sang a few things—lieder, according to the program—accompanied by a piano, of a loveliness so distilled and potent that Adam felt he was being poisoned.

Several times Adam found himself with tears in his eyes—not of grief, exactly, of course, and yet he seemed to be getting slowly torn to pieces by some clawing thing. So many of these people were, as his uncle had been, people one read about—artists, journalists, scientists—people who were fashioning the world they had received into the world he would be living in. How was it possible that he was here? He had always thought of his uncle as someone he himself had more or less imagined, but perhaps that was backwards; certainly his incorporeal uncle was more vivid than he was—perhaps it was he himself who had been conjured up from a pallid vision of the future, to materialize here…

His mother would be sitting with his grandparents in their kitchen, talking about the television news or the vegetable garden or church or the weather or the neighbors, in somber, brief, ritualized exchanges, the seemly code of his childhood that had to serve for all sorrows, all joys, all fears. It was grotesque that his uncle’s body had been shipped back there to the plains, where, in the uniform sunlight, it pleased God to monitor your soul for any fleck.

The prim, pastel-colored era that had completed his mother and ejected his uncle was long over, but in the region where all the family had grown up, it had been replaced by nothing. The exuberant 1960s were snobbishly passing it by when he was born, and now the venal 1980s were squeezing it dry. And the modest rural life there, with its piecrusts, its kind, tired waitresses in checkered uniforms, its Fourth of July parades, its rapidly abrading veneer of cheerfulness, had come to feel like something preserved in a bottle of chloroform, or a piteous, amateur, overrehearsed reenactment of an Eden that, come to think of it, might have been a little bit junky in the first place.

Everyone was filing out. “How are you getting to the house?” Vivian asked.

He looked at her.

“Clifford has a car,” she said. “Come.”

Clifford turned out to be a marvelously ugly, elegant old man who had spoken earlier, caustically and affectionately. It was hard to imagine him doing anything so plebian as driving a car, and indeed, his car turned out to be a glossy, pantherlike vehicle, driven by someone else entirely, a man in a uniform.

Adam was stowed in front, saving him from the strain of immediate new surprises. Engulfed in the purring of the motor as the magnificent city parted around the windshield, he could just hear the murmur of Vivian and Clifford conversing. At one moment, his name seemed to sound in the air, but when he turned, he saw that the two in back were both looking vacantly out the windows, their hands lightly clasped on the seat between them.

The house had chandeliers that looked like they had come from a mermaid’s palace. The floors were as shining as water. Huge mirrors brought the garden inside, with its cascading flowers. Adam stood at the open French doors watching the light splash through the leaves. The day, so fresh and glistening, seemed to contain every summer that had ever been and to promise more, endless more.

There were little, delicious things to eat, and large, fragile glasses of wine. Two musicians in white robes sat cross-legged on embroidered cushions, drawing out from another world a fragile, seeking cable of sound. Each note quivered for a moment in the air, dissolving, causing the walls to dissolve, dissolving the divisions between one thought and another, one feeling and another—rapture and anguish, resignation and yearning, twining together and dissolving…

The house lifted slightly off the ground. Adam clung to Clifford and Vivian. He wanted to say something…”You were friends of my uncle’s for a long time,” he eventually managed, and blushed at the inanity it had taken him so long to formulate.

“We’ve both known him—we both knew him—for around what?” Vivian turned to Clifford. “Oh, decades. Heavens—centuries, eternity. It feels like one second.”

“Young people think it’s some sort of accomplishment to know people for a long time,” Clifford announced. “But after the initial effort, you see, the matter takes care of itself.”

“It must be wonderful to have old friends, though,” Adam said, just as he realized how tactless this was, and in so many ways.

Clifford’s smile was the sort that concludes a dull business transaction. “Oh, you’re bound to find that you’ll have acquired some yourself. When you’ve lived long enough. You don’t even have to like them, not at all! There they are, whether you want them or not. Yes, old friends are marvelous. Stick to your old friends. Old friends are best. Because the things your new friends do to you will be every bit as dreadful.”

Clifford and Vivian chortled absently, and then, to Adam’s surprise, Clifford enfolded Vivian in his arms. Her cheek rested against his jaunty pocket handkerchief and the two of them stood there for a moment, swaying gently until he released her and turned away.

Vivian touched a fingertip to her eye, preventing a tear from spoiling her makeup. “Simon now, yes?” she said after a moment. “Are you up to it?”

Simon had regarded him steadily with the light, wolf’s eyes that seemed to see all the privations of winter forests. “I’ve picked out some of Phillip’s things for you,” he said. “Things I thought he’d especially want you to have. But you must stop by before you leave London and choose whatever you’d fancy.”

Adam emitted a clump of sound, but the weight of his uncle’s absence dropped onto it, crushing out nearly all its meaning. Simon stood courteously, head inclined until Adam had finished, patted Adam’s arm, and returned to the cordoned-off world where Phillip was waiting for him, fading.

Now, Adam had questions for Vivian, which he understood to be shockingly rudimentary. “Was it sudden?” he asked.

“Not sudden, but fairly rapid. We all knew something was wrong, but we didn’t know what, or how serious it was. Simon’s a doctor, though. I guess he pretty much knew what to expect, but he didn’t talk about it. I don’t know how much Phillip knew himself.”

They were at Vivian’s. When Adam had told her where he was staying, she’d said, “Oh, no, darling—you can’t. I mean, you can, of course, but why? I have a perfectly good spare room. You can just pretend it’s a hotel and come and go as you please.”

Come and go? he thought, as he put his pack down in the spare room. Why would he go anywhere? He was exactly where it turned out he wanted to be.

Her apartment, or flat, as she called it, was not far from Simon and Phillip’s house, in a part of London called Notting Hill, that looked like a nursery rhyme. The flat was small, and a little shabby, but everywhere you looked there were pictures or small clusters of toys or ceramic vases. The indigo night sky streamed in, trailing little moons and stars. Two dogs snoozed on a rug, and he had nearly tripped over a cat.

While Vivian went to get sheets and towels for him, Adam examined a cluster of framed photos. A girl in a tutu, her dark hair up in a bun, floated through the air toward another dancer, balanced on the point of his toe shoe, his arms outstretched to receive her. How young the girl was! Her tilted eyes were nearly closed in the bliss of anticipation. And there she was again, the girl, in another picture, wearing leg warmers and a baggy sweatshirt, leaning back, an arm around—yes, that was Simon, definitely it was, and both of them were laughing goofily. And there was Simon again, alone, under a tree, looking out over a misty valley…There were no photos of anyone who could be his uncle.

He was amazingly tired, and yet not quite sleepy. Vivian had made up the bed, and he lay there thinking of home, of the prairie, vast but incommodious, gorgeous and exhausting—the gargantuan farms looming in on his grandfather’s small, old-fashioned one, the daily drama of producing food, the revolve of the seasons, unremitting and grand, disrupted by periodic cataclysms…

Out the window was the charming street, and beyond, the houses and gardens and distant neighborhoods. London articulated itself, on and on, and all of England, then France, Germany—a smidgen of Asia…

Almost every bit of the world was unknown to him; almost every bit of it—past, present, and future—lay beyond the dome of his consciousness, invisible to him and unimagined, and yet just as real as anything his imagination could encompass. A phantom horizon shot out all around him, a sparkling mist of sky and water, in which faint continents were rising…

The planet turned in the sky, dotted everywhere with people and animals. Oop—there went a mastodon, lifting off Earth’s surface into the clouds! There went Uncle Phillip, now someone else, and more and more and more—the stratosphere was thick with balloonlike angels…

A rectangle of faint city light hung in the dark air. He grasped at a wisp of music that had been winding through his dream, but it was gone. The afternoon came back to him, the faces, his uncle…He was in London; that was a window, hanging there. He slid into place and felt around for a switch. A lamp awoke.

Not once, he realized, since he’d boarded the plane had he thought of Carol. Did he miss her? It was only a few weeks ago that they had broken up. Only a day before, he had missed her achingly, had missed making plans with her, meeting her at the café, fixing breakfast with her. He had missed her body, her lilting voice, her copious, glossy, slippy hair.

She had loved to go to the supermarket with him, to go running, to go out to dinner. She was always full of plans and projects, agile in her reasoning, a frighteningly good mimic…She could imitate all the lawyers at the firm where she was interning, and trot them out for his entertainment…They had never spoken of marriage, but still, he pictured a white wooden house near a meadow, where the children could play…

The last morning they spent together had started out with sunlight and pajamas and toothpaste and coffee, smiles and kisses—and then, quite unexpectedly, while he was carefully buttering his toast, there was a quarrel, swelling out of nothing, out of some infinitesimal mote. He wasn’t sufficiently ambitious, she said; it worried her. “I mean, ‘climatology’—what is it, exactly? Like, sometimes it rains, sometimes it doesn’t? I mean, do you want to be one of those guys on TV with the hair?”

He had looked at her, uncomprehending for a minute—was she kidding, or had she never heard a word he had said? Her pretty face was closed.

It was as if someone had thrown a rock through the window with a note tied around it: Someone Else. A partner at the firm, possibly? Possibly even one of the stuffy, swaggering men she had mercilessly lampooned for him—one who, of course, was sufficiently ambitious.

Maybe he had never heard a word she said. He rose to his feet, flinging his piece of toast onto the plate like a losing hand of cards. Her defiant expression had told him that his guess was right, and the indistinct little house in his mind, the indistinct little children, were funneled up from their meadow and spit out into oblivion.

Two AM, according to a clock on the little table next to the bed. He’d been asleep for a few hours, apparently. He shuffled into Vivian’s living room, with an unfocused notion that he might acquire something to drink there. Vivian was lying propped up on the sofa near a coffee table, with a book open in her hands. Her cigarette glowed in the dimness, and the window reflected the changing colors of a traffic light somewhere; it seemed impossible, in this light, that she could have been reading.

He sat down in an armchair on the other side of the table, which held an ashtray, an open bottle of wine, and a wineglass, nearly empty. She glanced at him, roused herself, and came back a few seconds later with another glass.

She poured him some wine and refilled her own glass. “Cigarette?” she said.

The impulse to rebuke her silenced him for a moment.

“Oh, right,” she said, “Well, sorry to break it to you, but all dancers smoke. Drink and smoke. We can’t eat, and we have to do something, don’t we?”

“Oh—“ he said. “But I mean—“

“Well, of course, not anymore. But, still, there it is, old habits…Anyhow, I teach at least. I’ve been lucky. No serious irreme—“ she interrupted herself to yawn “—emediable, pardon me, injuries. And some choreography.”

She had exchanged her glamorous suit for a pair of floppy trousers and a little T-shirt. She still wore her rings…

“It meant really a lot to Simon that you were there today. I don’t know how he got your family’s address out of Phillip. Phillip never spoke about his family, never. But I suppose, in the end, he must have wanted one of you to come over.”

The tip of the cigarette glowed again, like a breathing heart.

“No one told me,” Adam said. “They never would have told me. I went home for the funeral, to my family’s place, and I saw your letter lying with a heap of bills and things in my grandmother’s kitchen. Just completely by chance. I don’t know why it caught my eye.”

“Subliminal clues,” she said. “Great stuff, huh. You know, I tried to imagine it sometimes. What he came out of. God! He was so perfect…”

“There was no place for Phillip,” Adam said. It was like an astonishing proclamation that had just been handed to him to read aloud, and he used the name as if his uncle were an equal, a friend, a child he had looked out for. “Just no place.”

“Please,” she said. “You’re speaking to his niche!”

“I meant there, at home.” Adam sighed. Was there something about him? Did all women consider him a complete idiot?

“Feeble joke, sorry…I asked him once or twice what it was like. I wanted, you know—I wanted to be able to picture it, to see him in his natural…As if that would solve something. But for him, it was just…It was over…”

She shifted, uncomfortably, and as she lifted her head to awkwardly readjust a cushion behind her he saw her anguish, no longer restrained by the exigencies of the day. “It’s been a long time since you slept, I think,” he said. “You should sleep.”

“Look who’s talking,” she said. She shifted again, and lit a new cigarette from her old one.

“How did you meet Phillip?” he said, as if she really had been his uncle’s girlfriend.

“Oh, it was just—I just met him. In a shop. And we started talking. You know.” She grunted faintly, as though she were in pain. “It doesn’t matter.”

“Of course it matters,” he said. The girl in the photo floated toward her onstage lover’s arms. He split the wine remaining in the bottle between their glasses, and she made room for him as he sat down next to her on the sofa and put his hand against her forehead. She shifted again in exasperation, and he stroked her choppy hair back from her face. No fever…

“Here,” he said, putting his arms around her to calm her sudden, violent trembling. “Oh, God!” she said. She clamped her eyes shut, and a slick of tears slid from between the lids.

Nothing seemed ever to change in the world Phillip and he had come from, he told her, holding her to still the trembling; nothing seemed to happen. Everyone had been plunked down there on the sixth day and that was that—the past was a circle, and the future would be, too. There was only the winter death and spring rebirth, the ecstatic, shimmering summers, the harvest. Nothing broke the curve of the earth, the curve of the golden crops against the blue. Except, and it was an astonishing thing to see, through the wavering film of heat, when one of the storms appeared, marking the infinite sky.

First the air turned yellow. Yellow. And a black sort of veil dropped over it. And then the sooty yellow slowly turned a lush, rippling green. There were streaks of rose.

Then—everything went silent, silent and completely still. Except that way off in the sky, the black veil was spinning itself into a tiny, crazed, spinning black funnel, leaving the sky a clear yellow again, or green, as it twisted itself into shape after shape, skimming along toward you in the silence, like a dancer filled with god, growing larger and larger by the instant. All your senses were aroused and your whole body was alert, as though in expectation of some wonderful arrival.

The universe was poised, waiting. Then—a bird chirped nervously on a branch: a signal! Abruptly, a delicious fragrance released, and all the growing things for miles around started to shimmer and rustle. The air was chattering and filled with the soft thumping and scampering of little animals as they began to run.

It was the voice, especially, that was Phillip’s. Not only the timbre, but also the accent, the cadences—Phillip’s voice, assuming a presence in the room. She had forgotten how it felt, to be so light, to be lying in the sun. Concentrating fiercely, she gripped the glossy, wheat-colored hair in her fingers, and it glistened.

He had been in town once, he was saying, in the silent moment, the moment just before the trees began to groan and sway. And there, on the street where the post office and the shops were, a little fawn had come clop clop clopping, disoriented, out of a stand of trees and then right along the sidewalk. Its hooves rang out against the concrete, striking sparks, and the distant funnel swam in the creature’s great, dark, terrified eyes. An immense roar broke open the enveloping green; grainy darkness poured out, and there he was, the boy, scrambling down into the cellar of Dillard’s Stationery just as the storm ripped the roofs from the houses on the next street and sucked them into the sky!

He was still, thankfully, sleeping heavily when she disentangled herself from him in the morning and got up to feed the dogs and cat; she would be able to have coffee alone in her kitchen, to bathe…

She had made her way during the rest of the night in flickering gradations of sleep and wakefulness through a thick loam, like fallen leaves, of discarded and forgotten sensations.

…The dim afternoon when Laura Empson had been cast as Giselle, and there had been nothing to do but go out and walk in the freezing drizzle. Such desolation! That cold hand that grabs your heart from time to time and squeezes.

Laura was a beautiful dancer, she’d insisted to herself, and better suited to the role. And Laura was much older, Laura was twenty-six, if she didn’t dance the part now, she probably never would. She deserved the role. Lovely Laura. Spot on for that silly girl, Giselle. And besides, there were roles that Vivian was suited for that Laura wasn’t…There was plenty of time for her, yet. Plenty of time…

There was a little jingle of bells as she opened the shop door, and he glanced up from a desk, where he was sitting with his feet up, reading. She looked away instantly, but it was indelible—the impression of the wonderful gray eyes, the broad, handsome, intelligent face, the soft white shirt.

The shop was airy and white. Silk and lace, velvet and beads and chiffon, dresses that would have been worn by lovely women long ago, floated on excellent hangers.

She stood at a rack, moving the hangers methodically, with a tight heart, not seeing the dresses at all.

Was he looking at her? Or was he reading again . . .

She was twenty. There was plenty of time, assuming that her life were, after all, to work out. She was safely out of the corps, dancing less but dancing real roles…Still, so many things could happen—there were so many dangers ahead…

There was another little jingle from the door.

The girl entering the shop had been crying, that was clear, though the cold rain wouldn’t have done much for her appearance, either. Sorrow or weather, her face was red and swollen.

This girl glanced, just as Vivian had, at the man sitting at the desk. She glanced at him and then she stood uncertainly in the middle of the room, incongruous, surrounded by the delicate, lovely, costly clothing. It was unlikely that she could afford a single thing in the whole shop any more than Vivian could.

“Hello,” the man said. “Come in. Have a look around.” His voice was mild, kind rather than cheerful, and he had a wonderful accent, American, but very pure.

The girl went over to a rack on the other side of the room, and started moving the hangers as Vivian herself was continuing to do. She was wearing the shabbiest possible coat, an old, bedraggled fur thing of the sort that was to be found in junk shops at the time for a few pounds. The fur was hanging off, disgustingly, in chunks, as if she had been flayed.

The clicking of the hangers along the racks continued on both sides of the room, slowly and rhythmically, as if two clocks were each pedantically asserting different hypotheses.

While Vivian moved the hangers at her rack, she turned surreptitiously to watch the other fraud, who was also unable or unwilling to leave the shop. There was no doubt about it—the girl’s long, scraggly hair was wet from the rain, but you could tell, from just that bit of her profile, that those were tears sliding slowly down by her ear, her large nose…

Vivian pivoted back to the dresses as the man closed his book and got up from his chair. He disappeared behind a curtain, and returned with a little bottle of something. “Hold still, darling,” he said to the girl, and she did.

Vivian dropped her pretense of inspecting the clothing and simply watched as the man patiently, moving from one side of the coat to the other, from the top to the bottom, glued patches of peeling fur back onto it. The girl wearing it stood stock still. It was all taking a great deal of time.

“There you go, dear,” the man said, straightening up and patting the coat with the girl in it. “Back in business.”

For a moment the girl didn’t move, but then she…revolved, actually, just turned on one foot and absolutely melted into the man’s arms, sobbing loudly.

How small the bulky girl looked in his arms! While Vivian watched, the man held her, stroking the dreadful fur, stroking the ratty hair, making comforting sounds—just like a veterinarian—until the girl abruptly took control of herself, sniffed wretchedly, wiped her streaming nose on her abused sleeve, and exited without a word. The man returned to his desk and his book without a glance Vivian’s way.

“Excuse me,” Vivian said after a minute, and he looked up. Her voice was hoarse. “If I cry, can I get a hug, too?”

It had been pure luck; the shop wasn’t his—he had just been minding it that afternoon for a friend. They spent the evening together and then the next day, a Sunday, inside by a fire, though it was only September. Out the window, the air was dark gray and vaporous; the light came up from the earth, reflected by the yellow leaves, the rain-gleaming pavement.

He loved dance, as it turned out, and became a privileged fixture at performances. Now and again he would lounge in the dressing room after a performance and watch in the mirror as she stripped off her sylph’s mask and replaced it with a little light street makeup. His presence was calming and festive. They were all mad for him—the company, the musicians, the director, the choreographers…It was as if they had all always found Vivian special.

His work was demanding—he was already beginning to be known. Sometimes he would disappear into it for weeks at a time. And sometimes he would just disappear.

She was dancing radiantly in those days; her body was pure sunlight. They made each other laugh until they reeled like drunks, they walked around the city together at all hours, they lay tangled in her bed with music at top volume. They were like a jigsaw puzzle with only a few critical pieces missing. He never pretended that they could stay together. When someone tells you that he’ll always love you, she’d thought back then, it means he just never loved you enough.

But the 23 percent of him that was heterosexual, he said, had loved her passionately and exclusively. Love, passion, exclusive…Just words. Crack them open and they were empty.

For some time she had evaded Simon, beautiful Simon, who also loved dance, who also loved to watch her, admire her, who perhaps even envied her…So she invited her two indispensible friends to the dress rehearsal of an austere, rather short, superbly effective piece, in which she had the starring role. Afterward, the three of them went for champagne and oysters. She had left off any makeup at all, as if to be invisible while she watched the spectacle that was certain to begin in moments.

She had never remotely expected to be able to take up with Phillip again. After a time, she had chucked all her photos of him into a drawer, and it had been many years since she’d actually longed for him. After the commotion between the three of them, life had settled down to two and one. Eventually, she’d practically become a member of the household. Of course, she had other friends, too, and a few decent love affairs happened along that had consumed her interest at the time…It was sometime in there that her life as a dancer came to an end—the brutal price dancers pay for making beauty with their bodies.

Still, there was always the feeling that one would get around to being young again. And that when one was young again, life would resume the course from which it had deviated.

She cried so rarely. That afternoon in the shop, she had laughed instead as he rose to embrace her. But over the last twenty-four hours she had kept losing herself to an undertow of tears. All yesterday she’d felt brittleness fretting her bones, youth streaming from her in galaxies of sparkly molecules…

As she made her coffee, fed the animals, moved quietly around the kitchen for fear of waking the boy, that sensation started up again, the one that had been plaguing her these days, of counting, counting—measuring the distance she was slowly traveling from Phillip’s death, counting the hours until her next class, when the young dancers would come in, not carefree, of course, but with sorrows that might still be reversed or at least compensated for, counting the years since Phillip had left to move in with Simon, the minutes as they passed, while her little flat filled up with trinkets, toys, mementos…

The fourth—fourth!—speech, a heap of platitudes, flatteries, and bizarre flourishes, was building to an unsteady pinnacle of boringness. Any second now, at least, it was sure to finally topple over, and dessert could be brought out amid the rubble. But no—whole new incoherent embellishments were suddenly being encrusted on! How Phillip would have hated this whole event. How he would have laughed, she and Simon had said.

This current speaker was a professor of architecture, German. His hands were shaking slightly as he read on and on, but his voice was a placid monotone. This was no doubt the rough draft of a paper he was preparing for some academic journal. He himself had translated it, as he had modestly noted in his extensive prefatory remarks—hours and hours earlier.

Adam was at Vivian’s right, head pensively inclined, eyes lowered, arms folded—an attitude of devotional attention. His life, which had turned out, apparently to his surprise, to be one of conferences and dinners more or less of this sort, must have given him plenty of opportunity to perfect these stealth naps.

Across the table, Adam’s adorable wife, Fumiko, was surreptitiously playing with her napkin, and next to her Simon was turned slightly toward the speaker with imperturbable courtesy, eyebrows slightly raised.

As opaque as ever, Simon. What was he really thinking about? About Phillip? About the hospital or his patients or his students? About a rendezvous? One couldn’t think about what the professor was saying—it was impossible to know what on earth it was. The professor had little tears in his eyes now. Either he was deeply moved by his speech, or he was thinking of something else, himself.

Vivian willed a volley of darts Simon’s way and he turned, carefully, to glance at her. Age had treated him well. The lucky bastard was just as attractive—and as casually vain—at over seventy as he had been twenty years earlier! She crossed her eyes and stuck out her tongue so quickly that anyone who happened to look her way would think it was a hallucination. Simon turned back to the speaker with his almost insultingly decorous expression. Oh, that look must drive his colleagues mad!

Truly, she had never expected these plans of Phillip’s to be realized, and despite Simon’s façade of confidence, she doubted that he had either. Homes that supplied their own energy with sunlight and wind, that recycled their water, that returned to the earth what they took from it, and that, despite their humility, were comfortable and pleasing to live in. Phillip’s least glamorous project, the most profoundly ambitious and dearest to his heart, submerged for so many years in a swamp of bureaucracy, ridicule, and opposition, had been hauled back into the light by a firm of idealistic young acolytes.

People had already moved cautiously into the houses, no insoluble problems had yet appeared, the community was being written up in journals and in glossy magazines. The acolytes were no longer so young, and perhaps no longer so idealistic, but it had to be said that they had reason to be looking as pleased with themselves as they did tonight. Or almost as pleased with themselves, anyway.

It had been kind of Adam to take time out of his schedule to come over. He was something of a grand presence in his field these days, it seemed, owing to a few seminal studies he had conducted concerning the environmental impact of different sorts of energy. He himself had spoken tonight, and she had been surprised by a flood of affection for this unassuming young man. Well, he was hardly young, either, of course—he was well into middle age, but he seemed like a shy younger relative whom she was meeting for the first time since his childhood. And when he stood to make his brief remarks, she was warmed by something like pride.

In fact, she had been a little unnerved about the prospect of seeing him after all this time. Of him seeing her, truth be told. Well, but what could you do. She had steeled herself to sit down at the mirror and apply her makeup dispassionately, as if she were a nurse attending to the illness of a stranger. But when the somewhat portly fellow with thinning hair and glasses, who looked nothing at all like Phillip at that age, took his seat next to her, her heart had turned over. It was the glasses. He looked so breakable.

Months earlier, Simon had been asked by the event organizers to go over the guest list, and he had conscripted her. That had been a lovely evening, lolling about with Simon. They’d both pretended to be as snooty as teenagers about the prospect of this ceremonial, and when they finished their chore for the organizers they went out for a late dinner at a lively Lebanese restaurant and polished off quite a bit of wine. Eventually they’d stumbled into a taxi together, weak with laughter, their arms around each other. They saw one another so rarely these days! How to explain it? One never managed to see one’s friends any longer; they all said so. It was as if time, once a broad meadow, had narrowed to a slender isthmus.

“Who was that sitting next to you?” Fumiko asked as she and Adam walked back along Piccadilly. “The daffy old lady on your left? I talked to her for a moment before dinner, but there was so much going on.”

“Ah! Well. Yes, she was a good friend of my uncle’s. Vivian. She used to be a dancer.”

“Oh la la!”

Years ago, when his future seemed to have arrived, astonishingly, in the form of Fumiko, and the two of them had solemnly exchanged their histories, including a certain number of humiliating, ridiculous, or bizarre encounters, it was only Vivian of whom he had been unable to speak, as if at that delicate moment he could have done some damage to the girl in the photo and the mysterious lover toward whom she floated.

“And what about the other one, on your right, the blond in that dress?”

“Someone with money, I gathered. An enthusiast of Phillip. According to her, anyhow, she was instrumental in getting the project off the ground.”

“Well, here’s to the blond lady, then. It’s a fantastic thing.”

“Yes, it is.” Or an irreproachable thing, at least. Possibly if the principles had been widely adopted twenty-five or thirty years earlier, when his uncle had conceived of the project, excellent precedents could have been established and a certain amount of distraction avoided. But a few well-considered houses here and there were hardly going to appease the fierce sunlight and winds that had since been unleashed, or stay the torrential rains and violent floods.

“It’s so beautiful here,” Fumiko said. “I wish we could have brought Nell.”

“So do I. Maybe next year. Spring break.”

“You know there’s a terrible storm at home…”

“She’ll be all right. She doesn’t get frightened.”

“Don’t let’s go back to the hotel yet,” Fumiko said. “Let’s just keep walking and walking, please.”

It was May, just as it was when he’d first seen it, the city in bloom, regal and fresh. Warm, too, for London.

“Oh, wait—“ she said, and took out her phone. “I want a picture of you right there, to send to Nell.”

They were at a great iron gate, the entrance to a mysterious park. He and Vivian had walked exactly here, over twenty years earlier, the night before he’d returned to the States, and they had also stopped. “Has this been too strange?” she’d asked.

At the time he assumed she meant was it too strange to be half her age. It had never occurred to him until a minute or so ago that she meant was it too strange to be a proxy immortal. “No,” he’d said, “just strange enough.” She’d laughed and quickly kissed him. “You really are very sweet, you know. Just like Phillip.”

Tonight at the end of dinner, he’d kissed her powdery cheek. He helped her up from her chair; she seemed to be having some problem with a knee. He had not said, till next time, and neither, of course, had she.

Fumiko was fiddling with her phone. “A little to your left,” she said.

It would be just twilight at home. Their dignified, ethereal Nell would be comforting her pet mouse while the thunder and lightening raged above her. Almost instantly she’d receive a photo of what was just about to be the world’s very latest moment—by then so long elapsed.

“Okay,” Fumiko said. “Don’t move.”