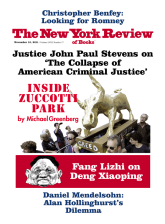

The Occupy Wall Street movement that began in Zuccotti Park in New York’s financial district on September 17 has grown to a degree that seems to have stunned even its organizers and most ardent supporters. From the first days, most news outlets, if they deigned to cover the movement at all, ridiculed the protesters for lacking a specific political agenda or concrete demands. They were “leaderless,” “directionless.” But less in this case has proven to be more: Occupy Wall Street’s vague, open-ended character has been crucial to its success. The catchphrase “We are the 99 percent” has a galvanizing succinctness, speaking directly to a wealth gap that has widened over the past decade to a point not seen since the Great Depression.*

The movement’s official Declaration of Occupation, released on September 29, is little more than a highly generalized incantation of the nation’s ills—“They have taken our houses…. They have poisoned the food supply…. They have continuously sought to strip employees of the right to negotiate.” But the movement’s assertion that it is an ally to “all people who feel wronged by the corporate forces of the world” has made it a blank screen upon which the grievances of a huge swath of the population can be projected.

The most common question asked about the protesters—after what do they want?—is, who are the organizers, who is behind it? Occupy Wall Street is the kind of deliberately elusive movement that, once the question is posed, its very premise is disputed: the word “organizer” is pregnant with just the kind of hierarchical connotations the protesters eschew. Nevertheless, there are organizers, and they are extremely astute, as well as reluctant to put forward their names. To them, “leaderless” is not an insult but an ideal.

By all accounts, the idea for the protest was hatched by Adbusters, a not-for-profit media organization that was founded in Vancouver, British Columbia, in 1989. After subscribing to their magazine, I received the following e-mail:

Dear Culture Jammer,

Thank you for joining our network. You are now part of a 90,000+ strong global network of activists, cultural creative’s [sic] and meme insurgents—a revolutionary force that, with your active involvement, just might reshape how power and meaning flow in the 21st century. Together lets live a little more on the wild side, launch a few telling cultural interventions and pull off some surprising pranks, jams and other essential mental resuscitations.

The antic, Dadaist tone is telling. This is a movement that addresses the mind, not the belly—“mental environmentalism,” the founders of Adbusters dubbed it, an antidote to the “pollution of our minds” by “infotoxins…commercial messaging and the…financial and ethical catastrophes that loom before humanity.” This sounds more like something that was cooked up in a university linguistics class than by conventional grassroots populists. But when combined with anarchism, the hacktivism of the WikiLeaks phenomenon, and the arcane theories of Guy Debord and the so-called Situationists on the May 1968 student demonstrations in Paris, a potently popular recipe appears to have emerged. It is, as Janet Malcolm put it in a different context, yet “another example of the Zeitgeist’s uncanny ways.”

In mid-July, a senior editor at Adbusters, Micah White, floated an e-mail to subscribers with the idea that they “flood into lower Manhattan, set up tents, kitchens, peaceful barricades, and occupy Wall Street for a few months.” As a result, a group of about one hundred people began meeting regularly in Tompkins Square Park to plan the protest, creating the NYC General Assembly, a bold and difficult experiment in direct democracy that has become the ever-expanding decision-making body of Occupy Wall Street. At some point during the summer, the loose collection of hackers known as Anonymous joined the protest. The members of Anonymous are identifiable by the Guy Fawkes masks they wear, and they are known for, among other things, their “denial of service” attacks that involve saturating target websites such as those of banks and credit card payment centers with so many requests that they overload and crash.

Much has been made of Occupy Wall Street’s conscious emulation of the mass protests last January in Cairo’s Tahrir Square—a comparison that a few weeks ago seemed like the height of delusional grandiosity, but that looks slightly less so now. Part of the emulation is strategic: the organizers of Tahrir Square used online networking sites not only to attract new followers, but to stage spontaneous protests that allowed them to stay ahead of the police. This is a new way of demonstrating that labor unions and traditional political organizers know almost nothing about, and that the hacktivists of Anonymous have mastered. Two members of Anonymous involved in the Wall Street protest who go by the names of Jackal and MotorMouth told the reporter Ayesha Kazmi of The Guardian recently of their “online flash mob” techniques of shooting out messages about street-meeting places and then appearing there as others gather.

Advertisement

The swift, almost simultaneous, presence of people on the street, often thanks to online messages, creates its own volatile brand of protest, in which violence of the sort that emerged in the Copenhagen demonstrations in 2009 is explicitly rejected. Kazmi writes that

when it emerged that a handful of activists were prepared to incite rioting and provoke the police days before Occupy Wall Street was to begin, Anonymous developed a Twitter application called URGE, launching an online campaign designed to quell potential violence. Anonymous “culture-jammed” Twitter with messages to keep protests peaceful, using top Twitter trends from around the world.

Tahrir Square also had the powerful advantage of a single unifying demand: the toppling of Mubarak’s government. As of this writing, the protesters of Occupy Wall Street are still debating whether to make a single political demand and what it will be, a tricky proposition that, it seems to me, they have done well to defer. Speaking to protesters in Zuccotti Park recently, I got the sense that they wished people would stop demanding a demand because the idea of one was of little interest to them. It seemed beside the point. What they cared about was the “process,” a way of thinking and interacting exemplified by their daily General Assembly meetings and the crowded, surprisingly well-mannered village they had created on the 33,000 square feet of concrete that comprises Zuccotti Park.

Some spectacular blunders by the police—especially the irresponsible use of pepper spray—placed the protest firmly in the media spotlight. Sympathizers then came streaming into the park in increasing numbers and at all hours of the day to volunteer some form of involvement. This, it seemed, was really the main project of the Occupy Wall Street organizers: to acquaint these new volunteers with their new version of democracy. It was impressive to watch the friendly solemnity of the teachers, if that’s what they were (they had probably volunteered only a few days before themselves), as they explained the protocols of the General Assembly. Why, they asked, curtail the growing mystique of Occupy Wall Street with something as ordinary as a political demand?

Demands could be made, of course. Micah White and other protesters have spoken of the need to reinstate the Glass-Steagall Act that, since 1933, had separated investment and commercial banking. (Glass-Steagall was repealed in 1999 to facilitate the merger of Travelers Group and Citicorp, now Citigroup, setting off what many believe to be a decade of ruinous speculation. Some of the Glass-Steagall provisions are reflected in the Volcker Rule included in the Dodd-Frank Act.) But to argue for Glass-Steagall is to infer that the existing financial institutions are essentially acceptable, when in truth some of the Occupy Wall Street activists apparently don’t believe the current banking system should exist at all. The same is true of tax reform: a tax on Wall Street would go to politicians controlled by Wall Street.

There was, according to this rhetoric, no way out but all the way out: a complete dismantling of the banking system and, as I heard many protesters call for, the abolition of the Federal Reserve. If this were overtly demanded, of course, the movement would collapse, since it proposes a change beyond almost everyone’s imagination, with no clear idea of how money and credit would circulate. What could be offered to the swelling ranks of sympathizers, however, were “mind bombs” and “anti-corporate epiphanies” (to quote from an e-mail Adbusters sent to me), a mental detox right there in Zuccotti Park.

Entering Zuccotti Park on October 4, a Tuesday, I felt as if I had walked into an impromptu forum. The park itself, which was renovated in 2006, is rather festive with its locust trees, its areas of planted chrysanthemums, and, near the southeast corner, an anodyne red sculpture by Mark di Suvero entitled Joie de Vivre that rises seventy feet into the air. The encampment was surprisingly well organized, with a “People’s Library” of plastic bins containing the kind of books you would find in a middle-class beach house. There was a phone-charging station, a medical area, a kitchen, and, along the southern wall of the park, a sleeping zone clumped with blankets, sleeping bags, rain tarps, and various personal belongings. A group of young men swept up refuse and put it in garbage bags. Spontaneous debates broke out among the constantly forming and dissolving clusters of people—about home schooling, vegetarianism, racial profiling on the part of taxi drivers who are racially profiled themselves…

Advertisement

Microphones and cameras were thrust forward without warning, belonging to members of the press or demonstrators, one couldn’t always tell. As often as not they came from a core group of protesters who were live-streaming the activities in the park on a Web network called Global Revolution. Their command post (though they would strongly reject the phrase) comprised the inviolable hub of the encampment: the computer equipment was guarded unthreateningly by the people’s security force who stood ready to form a protective phalanx around the area should trouble arise.

The mood was expectant, spirits generally high, though not without a dampening note of ambivalence. Several of New York’s most important unions—including those of health care workers, teachers, transit workers, and communications workers—had organized a march to Foley Square for the following day in support of Occupy Wall Street. The significance of these endorsements was enormous, conferring on the movement an instant legitimacy that many of its most seasoned members had not expected and that some had not wanted at all. Several protesters anxiously told me of their determination “to keep the process pure” in the face of the new outside pressures. “Horizontal, autonomous, leaderless, modified-consensus-based” democracy was still in a delicate, experimental phase. (So said an article, “Occupation for Dummies,” by Nathan Schneider in the movement’s broadsheet paper, The Occupied Wall Street Journal, whose initial print run of 50,000 was paid for by a campaign on the fund-raising site Kickstarter.)

It was impossible, of course, not to be swept up in the explosive rapidity of events. And there was little time to adjust to them. By the weekend of October 8, the tenor of the press coverage of the protest had become noticeably more respectful. And the protesters themselves, living for weeks in an inhospitable city park and withstanding police abuse in the name of ending corporate excess, had taken on to some of the public an aura of heroic innocence.

Seeing me take notes, a tall, elegant, rather knowing man who looked to be in his late forties approached me. He surprised me by introducing himself with his full name—Bill Dobbs. (His e-mail address was “duchamp,” a clue to his mindset.) He told me he had been an AIDS activist in the late 1980s, and for Occupy Wall Street he was involved in “outreach to the press.” When I asked him to characterize the protest, he answered, “It’s an outcry, pure and simple, an outcry that has cut through miles of cynicism.” He knew, he said, that in the absence of identifiable leaders, I could talk to anyone in the movement and that they, in turn, could represent themselves in any way they wished without accountability. This worried him, but only slightly. It was one of the drawbacks of direct democracy, which, “as you can see for yourself works beautifully here on the whole.” I mentioned Proposition 8 in California, an instance of direct democracy that overturned a state supreme court ruling that had legalized same sex marriage.

Bill nodded bleakly. He seemed unexcited about the union support. For years the unions had been organizing demonstrations that both the news media and the government yawningly ignored. The unions stood to benefit from the publicity at least as much as Occupy Wall Street. That this might in some way help the hospital workers, for example, did not seem something he had considered.

He seemed particularly scornful of the Democratic Party, elements of which were currently courting the movement. Paraphrasing Gore Vidal, he said, “There is only one party in the United States, the Property Party, and it has two right wings, Republicans and Democrats.” How, with this view, he expected to get people into positions of power he did not say. He insisted that the only way to run an honest movement was to staff it strictly with volunteers. “As soon as you have not-for-profit organizations their main concern becomes how to keep themselves going. For us, it’s different. No grants, no donors, no worries.”

At 7:30 PM, near the People’s Library, the General Assembly convened. There were about five hundred of us and, as far as I could tell, we were all members for as long as we hung around. From their perch atop the wall on the northeast section of the park, two young women moderated the meeting. “Mike check!” one of the women cried, and with a unison roar the crowd repeated her words. This was “the people’s mike,” used in lieu of bullhorns, megaphones, or other amplification devices that were prohibited because the protesters had no permit. When the crowd has to repeat every word, it shows; for example, during a speech by the Nobel Prize economist Joseph Stiglitz, things slowed down. But in the large crowd the repetition created a kind of euphoria of camaraderie. It also put you in the oddly disturbing position at times of shouting at full voice something you neither agreed with nor would ever have thought on your own.

On the agenda was the march to Foley Square the next day, but first the moderators wanted to know “if there are any concerns about our process.” For newcomers, the process was patiently explained, each phrase shouted back at the speaker as if to cheer her on. Anyone can submit a proposal to the General Assembly. To pass it must have 90 percent support judged by a show of hands, at which point it may be published online or in The Occupied Wall Street Journal. We were coached in the hand gestures that are the silent coded language of the protest. If you raised your hands over your head and wiggled your fingers like a partygoer in a group dance, it meant you agreed with what had just been said. Other gestures conveyed ambivalence, disagreement, and finally the blocking signal—a severe locking of forearms that, we were instructed, should be used only if you had “serious ethical concerns” with what was being proposed.

Speakers came and went, the unsynchronized human microphones throwing back the words in garbled waves. Everyone could feel he had spoken, even if all he had said was what was on another person’s mind. There was no possiblility for inflection; everything came in one volume and tone. Stuart Applebaum, head of the retail workers union, expressed his support with the air of a man paying tribute to an ally he was not sure he trusted or understood. His statement was brief and he rushed out of the park. To a grand wiggling of upward-held fingers, it was announced that “one hundred transit workers are now refusing to transport arrested protesters.” A woman recited the preamble to the Declaration of Independence until the assembly, in a collective groan in the form of the gesture for “wrap it up,” urged her to step down. A young man asked if acts of civil disobedience were planned for tomorrow’s march and was met with a hard silence. After a pause, a woman with a red bandana hiding her face said, “We are too smart to take the bait and answer this. Don’t give the NYPD what they want.”

Sitting next to me was an intense, exhausted man from Ohio who had been living in the park for eleven days. In a muted voice, he told me of the proposal he intended to present at a future General Assembly meeting. He hoped it would be added to the Declaration of Occupation, the closest thing to an official document the movement has published thus far. “I call it the Declaration of No Party. It’s meant to chase away speculators and opportunists who come down here and try to co-opt our movement.” He opened a spiral notebook and read:

We are not Left, we are not Right. We are the 99%. We are leaderless. Just stay away. We are here to end corporate influence in government. We don’t want to be like the Tea Party which was started by Ron Paul and co-opted by the Republican theocratic Right.

At Foley Square the next day, the unions delivered what they had promised: a large-scale demonstration denouncing corporate malfeasance. We were corralled into the square and gazed out at the police walking along the wide empty street, as if we were watching them on a stage. After a short conversation, a man handed me a sign: “Minor Literary Celebrities for Economic Equality.” A woman complained that there had been no leaflets advertising the march in her neighborhood on the Upper West Side. “Where’s the outreach, for crying out loud.” She obviously wasn’t on the contact list of Anonymous’s online flash mob. In any event, she was concerned that the march would hurt Obama—making her precisely the kind of Democrat some of the Wall Street protesters regarded as obsolete, fretting over the prospects of a President who, they believed, had sold them out but who, as it happened, said of their movement, “I think it expresses the frustrations that the American people feel.” I ducked into a bar with a group of Verizon workers who had nothing but good things to say about “those terrific kids in the park.”

At dusk on October 5, people were pouring into Zuccotti Park, drums pounding. The protest had reached its apotheosis. A girl sat on a sleeping bag feeding trail mix to a squirrel with a rope tied around its neck. A Billy Graham impersonator mock-preached into a megaphone, apparently unaware of the no-amplification rule. Two men held up a sheet projecting the movement’s Facebook page where the number of messages of support ticked higher by the second: 24,842 and rising. Cameras were everywhere—recording, broadcasting, feeding—and the people at the computer hub were hard at work, streaming it all live. The movement was a digitized global brain, a strange melding of the virtual and the actual, one a mirror of the other, both unspooling simultaneously in real time. The filmmaker Michael Moore arrived (it was the third time I had seen him in the park in two days), standing near the di Suvero sculpture, his voice drowned by the echo of the people’s mike, his face lit up in what seemed to be a state of ecstasy. “This movement has come together. Not because of a douche bag organization, but because the people wanted it. Let’s keep it like this. Do not let the politicians co-opt you!”

Protesters compared notes on the New York jails they had been in, sharing the latest rumors about Anthony Bologna, the deputy inspector who pepper sprayed three girls during a march on September 24, launching the movement’s rise. News that Steve Jobs had died circulated. He was the rare one-percenter whose demise provoked a moment of sadness in the park, no matter that Apple had recently surpassed Exxon as the American company with the highest market value.

A handful of protesters scuttled out of the park and headed toward the Stock Exchange on Wall Street. By 8:30 PM, hundreds of police had arrived, setting gray metal barricades along the Broadway entrance to the park, squeezing the crowd back inside. Several protesters slipped out and were immediately handcuffed and hauled into waiting wagons. The protesters inside the park pressed against the metal gates, some wanting to dare the police and charge out toward the Stock Exchange, that mythic fortress two blocks away in the dark. In a panicked voice, a woman attempted to find a consensus, using the General Assembly procedure, opening debate on whether they should cross the line. “We can’t let ourselves turn into a mob!” she shouted.

The face-off ended mildly, with twenty-three arrests; an hour later the park had thinned out and most of the police had dispersed. Remarkably, the mums had not been trampled. There was no graffiti anywhere, only handmade signs. In my time in the park, I didn’t see any drugs or alcohol, except for a man discreetly drinking beer from a plastic gallon milk jug.

It’s impossible to predict what will happen to the movement. It seems a delicate, almost ethereal process, designed for small groups, though new General Assemblies are constantly being established—as of October 9, protests had spread to 150 cities. Protestors are continually coming up with new ways to get their anticorporate message across: on October 9, a group of clergymen paraded through Zuccotti Park with a giant papier-mâché effigy of the biblical golden calf, modified to resemble the famous statue of the charging Wall Street bull. Until now, the movement has seemed protected by public opinion. The police have been reluctant to crack down on a group that, incongruously, has won expressions of sympathy, with suitable cautiousness, from President Obama, Ben Bernanke, Nancy Pelosi, and Vice President Biden. Still, in response to Mayor Bloomberg’s announcement on October 12 that the occupants would have to temporarily leave the park for it to be cleaned, confrontation was likely as this article went to press.

Anne-Marie Slaughter, the well-known Princeton professor of international affairs, writing in The New York Times, points out that from the first days of Occupy Wall Street news outlets in the Middle East paid close attention. Referring to the Tunisian vendor whose self-immolation set off the Arab Spring, she writes:

Go to the Web site “We Are the 99 percent” and you will see the Mohamed Bouazizs of the United States, page after page of testimonials from members of the middle class who took out mortgages to pay for education, took out mortgages to buy their houses…worked hard at the jobs they could find, and ended up…on the precipice of financial and social ruin.

The protesters in Zuccotti Park seem to have heralded the membership of a significant portion of our population in a new form of Third World, a development that our media and government appear to have been the last to absorb.

—October 13, 2011

Postscript, Monday Oct. 17: As Occupy Wall Street enters its second month, the status of Zuccotti Park as the symbolic nerve center of the movement seems more established than ever. On the night of Wednesday, October 12, Mayor Bloomberg made a surprise visit to the park, announcing that, at the request of Brookfield Office Properties, which owns and maintains the site, it would be cleared for cleaning. Afterward, protesters would be free to return as long as they obeyed the rules of the park, which include no storing of personal belongings, sleeping, or lying down.

The order, as with almost every attempt by the city to defuse the movement, seemed only to increase public sympathy for the protesters, revealing the depth of their support among some of the city’s highest-ranking elected Democratic officials. After conversations with City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer, and Daniel Squadron, a state senator, among others, Richard Clark, the chief executive of Brookfield, withdrew his request to the mayor for police “assistance” just before midnight on Thursday. Bloomberg appeared somewhat chagrined at Clark’s reversal, claiming on Friday that Clark had succumbed to “threatening” calls from the officials, and warning that in the future, “it will be a little harder…to provide police protection” should Brookfield change its mind.

In fact, it seems that what might have been a serious, possibly violent confrontation was averted. Unaware that the order to dislodge them at 7:00 AM Friday morning had been rescinded the night before, thousands of protesters (including hundreds of union members responding to an e-mail message Thursday night from the AFL-CIO) swarmed the park, planning to form a human chain around its perimeter to keep police from entering.

Their victory provided yet another boost to the protesters’ growing sense of confidence. The following day, Saturday, October 15, they staged a large, mostly peaceful march to Times Square, one of a series of simultaneous demonstrations that took place in eighty countries around the world. For the time being, at least, the protesters’ continued presence in Zuccotti Park seems secure.

This Issue

November 10, 2011

Our ‘Broken System’ of Criminal Justice

The Real Deng

-

*

The Washington Post has calculated that in 2010 the top 1 percent made a minimum of $516,633, with an average total wealth per person of $14 million. See Suzy Khimm, “Who Are the 1 Percent?,” October 6, 2011. ↩