Simon Wiesenthal’s legend is well known: the survivor of a succession of concentration camps, he was the Nazi hunter who tracked down Adolf Eichmann and brought to justice such monsters as Franz Stangl, the commandant of Treblinka, the most murderous of death camps, and Hermine Braunsteiner, the whip-wielding “Mare of Majdanek.” He was received by presidents at the White House, and had among his more surprising friends in high places German Chancellor Helmut Kohl and, once he had been released from Spandau prison, Albert Speer.

Countless honors were bestowed on him, among them the first honorary degree granted a Jew by the Jagellonian University in Kraków in its 610 years, the US Congressional Gold Medal, and the Golden Cross of Honor that the president of Austria brought to Wiesenthal’s bedside when he was nearing death. A prolific author of autobiographical texts1 as well as two novels and other writings, he has been the subject of several biographies, the most recent and the most fully documented of which is Tom Segev’s wise and balanced work. An Israeli historian and journalist, Segev had access to previously unavailable materials, including those lodged in the Israeli State Archive. Surprisingly, he was also privy to documents in the possession of the US official Eli M. Rosenbaum, Wiesenthal’s Inspector Javert–like tormentor during the last fifteen years of his life.2

Practically everything known about Wiesenthal up to May 5, 1945, when American troops liberated the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria, where he was a prisoner, is based on what he said in his books and countless articles, speeches, and interviews.3 By then he was thirty-six; he had been through the hell of four camps. The discrepancies in his accounts, however, matched by a tendency to embroider and exaggerate, fed an undercurrent of skepticism about Wiesenthal’s recollections, and opened him to slurs impugning his conduct during the war.

Wiesenthal was born on December 31, 1908, in Buczacz, Galicia, a very small town southeast of the city then called Lemberg. Lemberg became Lwów at the end of World War I, as a Polish city. It is now Ukrainian Lviv. There was no lack of Jews to exterminate in Galicia. Before World War I, some 870,000 Jews lived there, about 20 percent of the population. Buczacz, birthplace of the Hebrew writer S.Y. Agnon as well, had a population of nine thousand, of whom six thousand were Jews,4 the balance divided evenly between Ukrainians and Poles.5 Depending on which biography you read, Wiesenthal’s father was either a local agent for a sugar-manufacturing company or a wholesale commodity merchant dealing mostly in sugar. His uncle was a baker; his grandfather kept an inn.6 After World War II, Wiesenthal claimed that his parents had spoken German to each other, and that it was also the language he used with his mother. It is far more likely that this lower-middle-class family spoke Yiddish at home,7 which would be consistent with little Simon’s having been sent at the age of four to a cheder, a religious school.

Called up as a reservist, Wiesenthal’s father was killed in action in 1915. As the Austrian front crumbled in the east, the advance of Russian troops—and the prospect of pogroms that would attend their arrival—frightened Galician Jews, especially those who lived in small towns like Buczacz. Wiesenthal’s family fled first to Lwów and then to Vienna, where they lived in Leopoldstadt, the heavily Jewish lower-class district. As soon as the war ended, Wiesenthal’s mother decided it was safe to return to Buczacz. At the school he attended in Vienna the classes were in German. Back in Buczacz, he learned or relearned Polish and went to a Polish secondary school where he met Cyla, the girl he was to marry.

At twenty, he passed on the second try the matura, or final examination, that should have entitled him to attend a Polish university. The nearest university was in Lwów but, according to Wiesenthal, Jews taking the entrance examination there were intentionally given failing grades. The solution was to go abroad, in his case to Prague. Since he knew no Czech, he matriculated at the Deutsche Technische Hochschule Prag, where the German language was in use. He studied architecture. In 1932 he returned to Lwów, managed to gain admission to the university, and then to combine study with work for a building firm. In 1936 he married Cyla, and apparently, at the end of 1939, obtained a degree that entitled him to be called Herr Ingenieur, no trifling matter in title-conscious Austria.

German troops, accompanied by Ukrainian auxiliaries, entered Lwów on June 28, 1941, and Wiesenthal and his wife and mother were caught in the vortex of the Holocaust. As Segev puts it, at the time

Advertisement

there were between 160,000 and 170,000 Jews living there. By the time the Russians returned and drove the Germans out three years later, there were 3,400 Jews left, and one of them was Wiesenthal. During the Nazi occupation he lost track of his mother and his wife, but he was alive.

Horrors began promptly. They included in Wiesenthal’s case forced labor in the Ostbahn Ausbesserungswerke (OAW; Eastern Railroad Repair Works) yard in Lwów, and imprisonment in the Janowska concentration camp on the city’s outskirts. Segev writes that by a remarkable stroke of luck Wiesenthal was able to establish contact with the Polish underground while he worked for the OAW, and to obtain false Aryan papers for his wife. Cyla had the required Polish look that allowed her to pass during the remaining war years for a Catholic Pole, first in Lwów, then in Warsaw, and, finally in Germany where she was a forced laborer.

Another near miracle to which Segev also gives cautious credence was the benevolent protection of two good Germans who were Wiesenthal’s bosses at the OAW. They made it possible for him to act almost like a free man in the railroad yard; he worked in an office with a telephone, was cut in on the bribes paid to his good Germans by civilian contractors; he obtained weapons for the underground and kept two pistols for himself in the desk drawer of one of his bosses.

One of the good Germans died during the war, but Wiesenthal got in touch with the other afterward, inviting his former labor camp boss to his daughter’s wedding years later. As Segev observes, Wiesenthal had no reason to make up a story showing that he had suffered less than others during the war, which might be construed as evidence of collaboration with the Germans; and Segev found several witnesses who confirmed his account of his job. Still, according to Segev, it seemed “as if the main force driving him after the war was the need to prove that he had not been one of the villains.”

The fourth and last of the concentration camps through which Wiesenthal passed was Mauthausen, located in Upper Austria close to Linz, Hitler’s favorite city, and designed to kill by harsh labor. American troops liberated the camp on May 5, 1945. By then Wiesenthal, by build tall and burly, had been imprisoned since mid-February in the camp’s barracks for sick prisoners and weighed less than a hundred pounds. He saw the first American tanks at about ten in the morning. “People ran up to [them],” he remembered. “I also ran. But I was so weak that I couldn’t walk back. I crawled back, on all fours.”

He recovered his health rapidly and talked his way into jobs with the American military—an army war crimes unit and the local bureau of the counterintelligence corps—and became the head of local refugee groups with important-sounding names, as well as a representative of the Joint Distribution Committee, a Jewish relief organization working with DPs. The American connection, which involved identifying and apprehending war criminals, led directly to his life’s work: creating a database of Nazi criminals, tracking them down, and bringing them to justice. He had thought that Cyla was dead; he learned that in fact she too had survived. They were reunited in the fall of 1945, and their only child, a daughter, was born one year later. Not long afterward, Wiesenthal made a surprising decision: he and his family would live in Linz, in spite of abiding Austrian anti-Semitism, xenophobia, and hostility to refugees living among them. The explanation Wiesenthal gave over the years boiled down to a need to remain near his “his clients,” the war criminals. In September 1947 his connection began with the client who would make him famous, Adolf Eichmann.

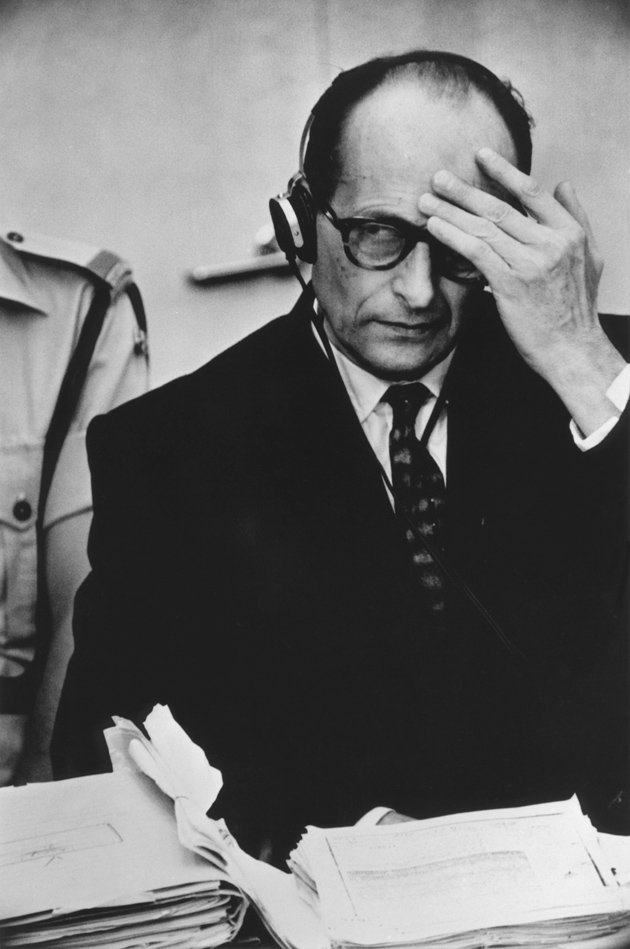

The search for Eichmann defined Wiesenthal as the foremost Nazi hunter, and ultimately embroiled him in bitter disputes about the contribution he had really made to his capture. His first attempt at autobiography was Ich jagte Eichmann (I Hunted Eichmann). He finished the book and found a publisher six weeks before the Eichmann trial started on April 11, 1961. The book was a commercial success and received a great deal of publicity. Wiesenthal, in Segev’s words,

relished finding himself at the center of this tale [of the capture of Eichmann]. But already, less than four weeks after the announcement that Eichmann had been taken [he was kidnapped in a suburb of Buenos Aires by Mossad agents on May 11, 1960], Wiesenthal sensed the stirrings of a future war for the glory, and he was very careful not to ascribe the actual abduction operation to himself. “My part in the final phase of the operation was more than modest,” he wrote to Yad Vashem. “Perhaps the best way to describe my achievement is that last autumn I revived the matter with new evidence.”

In fact, Wiesenthal had done more. Although his early attempts to find Eichmann had failed, in 1947 he learned that Eichmann’s wife had applied to the Austrian local court to have him declared dead—a ploy used by families of war criminals still at large to remove them from “wanted” lists—and he was able to have the application denied.8 Subsequently, on the first day of 1953, one of his contacts told him that Eichmann’s wife and children, who had disappeared from the Austrian town of Altaussee during the summer of 1952, had emigrated to South America, where Eichmann was working at a water plant.

Advertisement

Wiesenthal sent a copy of the contact’s letter to the Israeli consul in Vienna. A year later he found out from a fellow philatelist, an Austrian baron who had served in Wehrmacht intelligence, that one of the baron’s acquaintances had seen twice “that filthy swine Eichmann, who dealt with the Jews. He is living near Buenos Aires and working for a water supply company.” The information turned out to be correct, and Wiesenthal again reported it to the same Israeli consul. Having done so, Wiesenthal expected the Israeli government to take some action, and was disappointed when there was none. As Hannah Arendt observed:

The puzzle is not how it was possible to discover Eichmann’s hideout [in 1960], but, rather, how it was possible not to discover it earlier—provided, of course, that the Israelis had indeed pursued this search through the years. In view of the facts, this seems doubtful.9

The next development came in March 1954, when the Israeli consul came to Linz and told Wiesenthal that Nahum Goldmann, the imperious president of the World Jewish Congress (WJC), wished to receive a report on the status of the search for Eichmann. The consul further revealed that the request had been made some months earlier, that Goldmann had said he was acting at the behest of the CIA, and that he, the consul, had forgotten to do anything about it. Wiesenthal quickly summarized all the information he had, including the probability that Eichmann was in Argentina. Wiesenthal’s report was transmitted to the CIA by the WJC, but Goldmann didn’t acknowledge its receipt.

Instead, some months later, a rabbi working for Goldmann wrote to Wiesenthal asking for Eichmann’s exact address in Argentina. Wiesenthal replied that he didn’t have it, but that if he received a contribution of $500 or perhaps less he would send someone to Buenos Aires who could obtain it. That request was disregarded, and Wiesenthal, feeling slighted, never forgave Goldmann. Finally, in late 1959, Wiesenthal sent to the Israeli ambassador in Vienna a detailed report on Eichmann, and, two months later, he also sent recent photos of Eichmann’s brother Otto, whom he closely resembled. These photographs were given to the Mossad, and one of the agents who took part in the abduction of Eichmann later acknowledged that they had helped him to identify his quarry.

Eichmann’s capture and trial in Jerusalem were a triumph for Israel. The story of the Holocaust as told there on the world stage, and in Raul Hilberg’s Destruction of the European Jews (1961), finally broke through the embarrassed silence surrounding it. It galvanized West German authorities, who moved with spectacular results to prosecute notorious war criminals who had been living peacefully in Germany, some of them having been previously “denazified.” There were parallel developments in other countries, including Poland, the GDR, the USSR, and France.10 It was also a moment of triumph for Wiesenthal, and Segev observes that “the ten years that followed were the most important and the most exciting of his life.”

However, conflicting claims about responsibility for Eichmann’s apprehension mired Wiesenthal in bitter controversy, most notably with Isser Harel, who had been at the time the head of Israeli secret services, and with the WJC. Harel was angry because Israel’s denial of any Israeli official involvement in the abduction of Eichmann on Argentinean soil had deprived Israelis of the opportunity to take full credit for the operation. The resentment was no doubt compounded by the Mossad’s embarrassing failure to act on Wiesenthal’s report to Goldmann, a copy of which it had received already in 1954.

Harel denied ever having seen the report; by focusing on minor inconsistencies he picked apart Wiesenthal’s story about information received from the Austrian baron and belittled the importance of the photos of Eichmann’s brother that Wiesenthal had obtained. In a book he wrote on the Eichmann abduction he did not mention Wiesenthal, and in interviews with journalists asserted that Wiesenthal had no part in the efforts to find him. He returned to the charge in an unpublished manuscript that Segev calls “small-minded and quarrelsome.” Harel gave a copy of the manuscript to Eli Rosenbaum, by then the head of the US Office of Special Investigations, who in his Betrayal quoted it as proof that Wiesenthal was an impostor.

Major blunders followed Wiesenthal’s moments of triumph. The first was his poor management of his relations with Bruno Kreisky, the first Jewish chancellor of Austria. The second involved Kurt Waldheim: his election first to the office of secretary-general of the United Nations, and then to the presidency of Austria.

Segev is excellent on the Wiesenthal–Kreisky wars, a row that commenced in 1970 and ended only with the chancellor’s death in 1990.11 Born in 1911 into a wealthy and assimilated Viennese Jewish family in Vienna, Kreisky had had a brilliant political career. He was a lifelong socialist and a member of the Austrian Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ). After spending the war years in Sweden, he became a counselor to the president of Austria and the equivalent of his chief of staff in 1951. Eight years later, he was made the minister of foreign affairs. His party was out of power in the second half of the 1960s, but in 1970 it won a plurality of votes and Kreisky became chancellor at the head of a minority government. Starting then, from election to election, the recurring political question in Austria was whether the SPÖ with Kreisky at the helm would be able to govern alone or would have to enter into a grand coalition with the conservative Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), or a small coalition with the far right Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), whose few seats in the parliament were typically sufficient to give the SPÖ a majority in the parliament.

With many former Nazis at large in Austria and some officials with dubious records in Kreisky’s cabinet, open conflicts broke out between Wiesenthal and Kreisky. Underlying the animosity of the two men—Kreisky believed that he could not be squeamish if he was to govern, while Wiesenthal was determined to unmask Nazi party and SS members—however, was something deeply personal. For Kreisky, Wiesenthal was one of the embarrassingly crude Jews from Eastern Europe whose influx into Austria, Germany, and France had stoked the fire of pre-war anti-Semitism. Wiesenthal, for his part, saw in Kreisky a Jew determined to distance himself from his Jewishness. Their antagonisms and skirmishes turned into open hostilities in 1975, when Wiesenthal learned that Kreisky was negotiating a possible coalition with Friedrich Peter, the head of the FPÖ, offering to make Peter his vice-chancellor. Peter had served in one of the SS brigades whose involvement in mass murders of Jews was fully documented.

In the event, the SPÖ won by a small majority, and no coalition was formed. Nevertheless, directly after the election, although there was nothing that linked Peter personally to any crime, Wiesenthal made his dossier on him public at a well-attended press conference. Kreisky never forgave this gratuitous provocation. In the ensuing row, he accused Wiesenthal of using Mafia tactics and, much more serious and unpardonable, of having survived the war by collaborating with the Gestapo. There was no basis for this heinous charge, which had, apparently, been fabricated by the East German and Polish intelligence services. The libel suits that followed ended with a judgment against Kreisky and an award of substantial damages that were never paid.12

Wiesenthal was untypically negligent in what became the Waldheim Affair. The first instance of his carelessness was his response in December 1971 to the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith, which wanted to know what the new secretary-general of the United Nations had done during the war. Wiesenthal immediately advised the ADL that nothing prejudicial was known in Austria, and that gossip by Waldheim’s political adversaries could not be verified. He added: “I myself know Mr. Kurt Waldheim very well. I personally had only the best impression of Mr. Waldheim during my contacts with him.”

Fatal words: it would have been easy and consistent with Wiesenthal’s normal practice to check into documentary history, and to focus on the telltale omissions in Waldheim’s official record. In the years that followed, Waldheim became openly critical of Israel, condemning, for example, the IDF’s rescue at the Entebbe, Uganda, airport of hijacked passengers aboard an Air France jet. In 1979 Wiesenthal was a asked by his friends at Yad Vashem to scrutinize Waldheim’s past once again. He obtained information from the American-controlled archive in Berlin showing that Waldheim had not belonged to the Nazi party or any other Nazi organization. However, he had also obtained unofficially, through the German publisher Axel Springer, from an archive under French control, a document that described in detail Waldheim’s military service during the war. It showed plainly and conclusively that Waldheim had lied about his wartime record. He had claimed that he had been a doctoral student in Vienna when in fact he served as an intelligence officer in the Balkans.

Had Wiesenthal studied the new information he would have realized that the notorious German army unit with which Waldheim had served had committed war crimes in the Balkans and Greece, transferring civilians to the Gestapo and deporting Greek Jews to death camps, among other crimes. Its commanding general had been convicted after the war by a Yugoslav tribunal and hanged. But Wiesenthal did not report these findings. Instead he telephoned his contact at Yad Vashem and said that Waldheim had not been a Nazi.

The Waldheim scandal probably would not have erupted if, having been denied a third term as secretary-general of the UN, Waldheim had not decided in 1986 to run once more for the office of president of Austria (he had been defeated in the 1971 election), and if the World Jewish Congress had not needed a new cause. Segev points out that, in the mid-1980s, with the cold war ending and the fight for Jewish rights in the Soviet Union losing momentum, the WJC felt the need to energize its Jewish-American constituency; and to do so it backed the campaign against Waldheim. As Eli M. Rosenbaum told it in his book Betrayal, Israel Singer, at the time the secretary-general of the WJC,13 dispatched him to Vienna to look into the Waldheim case.14 Rosenbaum was the newly appointed general counsel of the WJC, having previously served for three years as a lawyer in the Justice Department’s Office of Special Investigations.

Waldheim’s lies were soon uncovered. Eventually, the WJC succeeded in having his name placed on the list of several tens of thousands of suspected war criminals and criminals of all other sorts who are denied entry to the United States. In Waldheim’s case, the cause was his undeniable service as an intelligence officer in a Wehrmacht unit that committed war crimes.

Notwithstanding the WJC’s campaign and Rosenbaum’s investigation, Waldheim was elected president, in a campaign marked by a wave of virulent anti-Semitism that did not recede after the election, and a rise in the votes cast for the FPÖ led by Jörg Haider, a polarizing extreme right figure. Eighteen months later, a panel of five independent historians from Switzerland, Britain, West Germany, and Israel came to the conclusion that although Waldheim had not himself committed war crimes, he had known about them and had not protested, while personally he “had had little practical possibility of influencing events.”15 This squared with the conclusion of the Israeli attorney general, who concluded that the WJC’s evidence merited an investigation but was not sufficient to convict Waldheim under Israel’s Nazi Punishment Law.16

Although ultimately it appeared that Wiesenthal was right—Waldheim was a cynical and shameless liar but not a Nazi or SS officer—the price he paid for his blunders in the Waldheim affair was high. It may have included his having forfeited the chance to receive the Nobel Peace Prize that many believed would be his in 1986. He thought it was more likely that he would have to share it with Elie Wiesel. But Wiesel received the prize alone.

In the late Sixties, Wiesenthal wrote about an incident that took place when he was imprisoned in the Janowska concentration camp. Sent with other prisoners to Lwów on a labor detail, he was put to work moving heavy equipment in the courtyard of the technical university, which had been converted into a military hospital for wounded German soldiers. A German nurse insisted that Wiesenthal follow her upstairs and left him alone in a room with a shape lying on the bed that turned out to be a German soldier wrapped from head to toe in bandages.

The soldier asked whether Wiesenthal was a Jew, and when Wiesenthal said yes, the soldier went on to tell him that he was a member of the SS and that his unit had participated in an atrocity—setting fire to Jews packed into a house—in a village in Ukraine. He asked Wiesenthal to forgive him so that he might die in peace. After a pause for reflection, Wiesenthal left the room without a word.

Having written the story, Wiesenthal asked a number of prominent people whether they thought that what he had done was morally right. Many of them replied, including Hannah Arendt, Günter Grass, Charlie Chaplin, Primo Levi, and Arthur Miller. Subsequently he published the story in a book, The Sunflower (1969), including in it his correspondents’ replies to his question as well as letters of those who did not choose to reply to the question and explained their reasons.17

The book was his third best seller, and it became a textbook used in many schools. Wiesenthal never deviated from his original insistence that the story was true. But many doubts have been voiced about its authenticity, particularly the improbability of a Jewish prisoner appearing at the bedside of a severely wounded SS man. Authentic or not, the story goes to the core of Wiesenthal’s Nazi-hunting enterprise.

Segev quotes a letter from Eva Dukes, an Austrian-American woman with whom Wiesenthal had a long relationship, in which she wrote about the wounded soldier:

You could almost have forgiven him, and as your suffering proves, you were closer to doing so than you realized then. It was largely your guilt toward your comrades and toward the dead that held you back, the dread of disloyalty. Apparently you were close to feeling, although incapable of saying, “Yes I forgive you.”

If Wiesenthal had forgiven the man, Segev believes, he might have been able to forgive himself, “and perhaps he would have shaken off the grip of the Holocaust that pursued him even more relentlessly than he pursued others…. He, who always tried to prevent the innocent from being punished, punished himself for a crime he didn’t commit.” Segev seems to believe that the crime was his having suffered, because of the decency of the two good Germans, considerably less than many other prisoners, indeed owing his life to those Germans. Perhaps that was one of Wiesenthal’s great sorrows; but it’s worth noting that like the survivors of other great catastrophes, Holocaust survivors are apt to be afflicted by feelings of guilt when they remember those around them who seemed more deserving but were lost. It is unlikely that Wiesenthal would have purged himself of that guilt by absolving the SS man of guilt for a crime that could have been forgiven only by his unit’s victims, and they, of course, were dead.

-

1

See Ich jagte Eichmann (Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Lesering, 1961); The Murderers Among Us: The Simon Wiesenthal Memoirs, edited by Joseph Wechsberg (McGraw-Hill, 1967); and Justice, Not Vengeance, translated by Ewald Osers (Grove Weidenfeld, 1989). ↩

-

2

See Eli M. Rosenbaum and William Hoffer, Betrayal: The Untold Story of the Kurt Waldheim Investigation and Cover-Up (St. Martin’s, 1993). ↩

-

3

Sources of information behind the Iron Curtain were as a practical matter unavailable, and the memories of witnesses who had survived the war were not necessarily more reliable than his. ↩

-

4

Wiesenthal, The Murderers Among Us, p. 24. ↩

-

5

Hella Pick, Simon Wiesenthal: A Life in Search of Justice (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1996), p. 29. ↩

-

6

Pick, Simon Wiesenthal, p. 30. ↩

-

7

Pick, Simon Wiesenthal, p. 30. ↩

-

8

Pick, Simon Wiesenthal, pp. 120–121. ↩

-

9

Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, A Report on the Banality of Evil (Penguin, 2006), p. 238. ↩

-

10

Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, pp. 14–15. ↩

-

11

Pick, Simon Wiesenthal, pp. 246–272. ↩

-

12

Pick, Simon Wiesenthal, pp. 241–254, 272–291. ↩

-

13

According to The New York Times, Singer was fired from the organization in March 2007 after a three-year controversy concerning his “lavish travel and other expenses” and “odd transfers” of $1.2 million between accounts in New York, Switzerland, and London. An investigation by the New York attorney general’s office concluded that Singer had violated his fiduciary responsibilities. See Stephanie Strom, “World Jewish Congress Dismisses Leader,” The New York Times, March 16, 2007. See also an earlier report by Amiram Barkat, “Israel Singer Fired from WJC for Allegedly Embezzling Funds,” Haaretz, March 22, 2007. ↩

-

14

Rosenbaum, Betrayal, p. 1. ↩

-

15

Pick, Simon Wiesenthal, p. 304. ↩

-

16

Pick, Simon Wiesenthal, p. 373. ↩

-

17

Simon Wiesenthal, The Sunflower: On the Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness (Schocken, 1997), originally published as Die Sonnenblume (Paris: Opera Mundi, 1969). ↩