Within hours of the death of Apple Computer CEO Steve Jobs, people began to show up at Apple stores with flowers, candles, and messages of bereavement and gratitude, turning the company’s retail establishments into shrines. It was an oddly fitting tribute to the man who started Apple in his parents’ garage in 1976 and built it up to become, as of last August, the world’s most valuable corporation, one with more cash in its vault than the US Treasury. Where better to lay a wreath than in front of places that were themselves built as shrines to Apple products, and whose glass staircases and Florentine gray stone floors so perfectly articulated Jobs’s “maximum statement through minimalism” aesthetic. And why not publicly mourn the man who had given us our coolest stuff, the iPod, the iPhone, the iPad, and computers that were easy to use and delightful to look at?

According to Martin Lindstrom, a branding expert writing in The New York Times just a week before Jobs’s death, when people hear the ring of their iPhones it activates the insular cortex of the brain, the place where we typically register affection and love. If that’s true, then the syllogism—I love everything about my iPhone; Steve Jobs made this iPhone; therefore, I love Steve Jobs—however faulty, makes a certain kind of emotional sense and suggests why so many people were touched by his death in more than a superficial way.

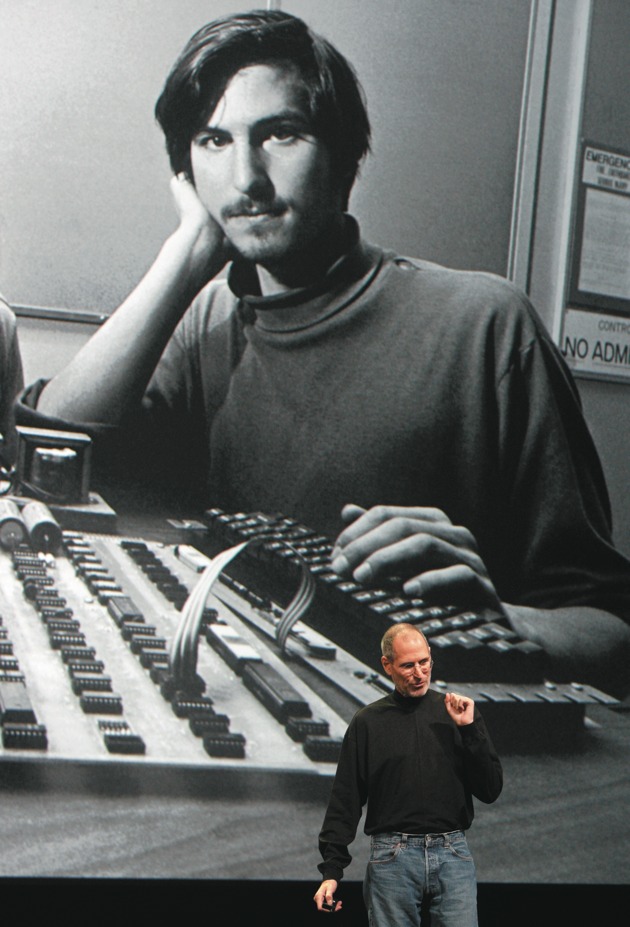

By the time he died in October at age fifty-six, Jobs was as much an icon as the Apple logo or the iPod or the original Macintosh computer themselves. Known for his casual jeans-and-black-turtleneck look, Jobs had branded himself and, by extension, his company. The message was simple: I’m not a suit, and we don’t make products for suits—suits being a euphemism for buttoned-up, submissive conformists. America loves its business heroes—just a few years ago, books about General Electric’s former chief executive Jack Welch, the investor Warren Buffett, and Chrysler’s Lee Iacocca topped best-seller lists—and it also celebrates its iconoclasts, people who buck the system and make it on their own terms. As Walter Isaacson’s perfectly timed biography makes clear, Jobs aspired to be both, living as if there were no contradiction between the corporate and the countercultural, and this, along with the sexy hardware and innovative software he bequeathed us, is at the root of the public’s fascination with him.

Isaacson’s biography—which is nothing if not a comprehensive catalog of Jobs’s steps and missteps as he went from being an arrogant, mediocre engineer who had been relegated to the night shift at Atari because of his poor hygiene to one of the most celebrated people in the world, widely credited with revolutionizing the businesses of personal computing, digital publishing, animated movies, tablet computing, music distribution, and cellular phones—is distinguished from previous books about Jobs by the author’s relationship with his subject. This is a book that Jobs solicited in 2004, approaching Isaacson not long after being diagnosed with cancer, and asking him to write his biography so his kids would know him, he said, after he was gone. Jobs pledged his complete support, which included full access to himself and his family with no interference or overt editorial control.

As was widely reported in the press in the run-up to the book’s release, Isaacson, who was unaware of Jobs’s diagnosis at the time, demurred. Five years later, after Jobs’s second medical leave from Apple, at the urging of both Jobs and his wife, Isaacson took on the project. Two years, forty interviews with the primary subject, and six hundred pages later, it was rushed into print just two weeks after Jobs’s death and a month before its scheduled publication date, which itself had been moved up from March 2012. Upon Jobs’s death, preorders for the book jumped a record 54,000 percent.

When Isaacson asked Jobs why he wanted him to be the one to write his authorized biography, Jobs told him it was because he was “good at getting people to talk.” Isaacson, who had been both the editor of Time magazine and the head of CNN, professed to be pleasantly surprised, maybe because two of his earlier, well-received, popular biographies were of men who could only speak from the grave: Benjamin Franklin and Albert Einstein. More likely, Jobs, who considered himself special, sought out Isaacson because he saw himself on par with Franklin and Einstein. By the time he was finished with the book, Isaacson seemed to think so as well. “So was Mr. Jobs smart?” Isaacson wrote in a coda to the book, published in The New York Times days after it had come out. “Not conventionally. Instead, he was a genius.”

Advertisement

While the whole “who’s a genius” debate is, in general, fraught and unwinnable, since genius itself is always going to be ill-defined, in the case of Steve Jobs it is even more fraught and even more unwinnable. In part, this is because the tech world, where most of us reside simply by owning cell phones and using computers, is not unlike the sports world or the political world: it likes a good rivalry. If, years ago, it was Microsoft versus Apple, these days it’s Apple versus Android, with supporters of one platform calling supporters of the other platform names (“fanboys” is a popular slur) and disparaging their intelligence, among other things. Call Steve Jobs a genius and you’ll hear (loudly) from Apple detractors. Question his genius, and you’ll be roundly attacked by his claque. While there is something endearing about the passions stirred, they suggest the limitations of writing a book about a contemporary figure and making claims for his place among the great men and women in history. Even though Isaacson has written what appears to be a scrupulously fair chronicle of Jobs’s work life, he is in no better position than any of us to know where, in the annals of innovation, that life will end up.

The other reason nominating Jobs to genius status is complicated has to do with the collaborative nature of corporate invention and the muddiness of technological authorship. Jobs did not invent the personal computer—personal computers predate the Apple I, which he did not in any case design. He didn’t invent the graphical interface—the icons we click on when we’re using our computers, for example—that came from engineers at Xerox. He didn’t invent computer animation—he bought into a company that, almost as an afterthought, housed the most creative digital animation pioneers in the world. He didn’t invent the cell phone, or even the smart phone; the first ones in circulation came from IBM and then Nokia. He didn’t invent tablet computers; Alan Kay designed the Dynabook in the 1960s. He didn’t invent the portable MP3 music device; the Listen Up Player won the innovations award at the 1997 Consumer Electronics Show, four years before Jobs introduced the iPod.

What Jobs did instead was to see how each of these products could be made better, or more user-friendly, or more beautiful, or more useful, or more cutting-edge (quite literally: there is a popular YouTube video making the rounds that shows the sleek new MacBook Air being used to slice an apple). A few years ago, in a profile in Salon, Scott Rosenberg called Jobs a digital “auteur,” and that description seems just right.

The template for Jobs’s career was cast in 1975, months before he and his friends set up shop in his parents’ garage in Los Altos, California, near Palo Alto. Jobs, who had dropped out of Reed College and moved back home, was hanging around with his high school buddy Steve Wozniak. Wozniak, a shy, socially awkward engineer at Hewlett-Packard, was drawn to a group of phone hackers and do-it-yourself engineers who called themselves the Homebrew Computer Club. It was at a club meeting that Wozniak saw an Altair, the first personal computer built from a kit, and he had the insight that it might be possible to use a microprocessor to make a stand-alone desktop computer. “This whole vision of a personal computer just popped into my head,” Isaacson quotes Wozniak as saying. “That night, I started to sketch out on paper what would later become known as the Apple I.”

Then he built it, using scrounged-up parts, soldering them onto a motherboard at his desk at night after work, and writing the code that would link keyboard, disk drive, processor, and monitor. Months later he flipped the switch and it worked. “It was Sunday, June 29, 1975,” Isaacson writes, “a milestone for the personal computer. ‘It was the first time in history,” Wozniak later said, ‘anyone had typed a character on a keyboard and seen it show up on their own computer’s screen right in front of them.'”

Wozniak’s impulse was to give away his computer design for free. He subscribed to Homebrew’s hacker ethos of sharing, so this seemed the right thing to do. His friend Steve Jobs, however, instantly grasped the commercial possibilities of Wozniak’s creation, and after much cajoling, convinced Wozniak not to hand out blueprints of the computer’s architecture; he wanted them to market printed circuit boards instead. They got to work in the Jobses’ garage, assembling the boards by hand. As Wozniak recalls it, “It never crossed my mind to sell computers. It was Steve who said, ‘Let’s hold them in the air and sell a few.'” It was also Jobs who pushed his friend to sell the circuit boards with a steep mark-up—Wozniak wanted to sell them at cost—and Jobs’s idea to form a business partnership that would take over the ownership of Wozniak’s design and parlay it into a consumer product. Within a month, they were in the black. Jobs was twenty-two years old. He hadn’t invented the Apple computer, he had invented Apple Computer. In so doing, he set in motion a pattern that would be repeated throughout his career: seeing, with preternatural clarity, the commercial implications and value of someone else’s work.

Advertisement

After the Apple I, whose innovations were all inside its case, Wozniak went to work on the Apple II, which promised to be a more powerful machine. Jobs, however, recognized that its true power would only be realized if personal computing moved beyond the province of hobbyists like the Homebrew crowd. To do that, he believed, the computer needed to be attractive, unintimidating, and simple to use. This was Jobs’s fundamental insight, and it is what has distinguished every Apple product brought to market since and what defines the Apple brand. For the Apple II itself, Jobs envisioned a molded plastic case that would house the whole computer—everything but the keyboard. For inspiration he looked to the Cuisinart food processors he saw at Macy’s. With those in mind he hired a fabricator from the Homebrew Computer Club to make a prototype, and an engineer from Atari to invent a new kind of power supply, one that ensured that the computer would not need a built-in fan; fans were noisy and inelegant.

Thus began Jobs’s obsession with packaging and design. Isaacson reports that when it came time to manufacture the Apple II case, Jobs rejected all two thousand shades of beige in the Pantone company’s palette. None was quite right, and if he hadn’t been stopped, he would have demanded a 2001st. Still, by any measure, the Apple II was a major triumph. Over sixteen years and numerous iterations, nearly six million were sold.

Despite the huge success of the Apple II, it turned out to be the out-of-town tryout for the computer that would become the company’s big show, the Apple Macintosh. (Nearly three decades later, the words “Apple” and “Mac” have become interchangeable in popular conversation.) Jobs jumped aboard the project when it was well under way, after being booted from a group at Apple working on a computer named Lisa that its developers, who had come over from tie-and-jacket Hewlett-Packard, envisioned selling to businesses and large institutions. The Mac, by contrast, with a target price of $1,000, was meant to appeal to the masses. It would be the Volks-computer. By the time it was released in 1984, the price had more than doubled, in part to cover the heavy investment Jobs had made in promoting it, making it one of the more expensive personal computers on the market.

Both the Lisa and the Mac shared one critical trait: they were built around a novel user interface developed by the engineers at Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) that manipulated every pixel on the screen using a process they’d pioneered called bit-mapping. The geeky commands of the text-based DOS operating system that had been necessary to get a computer to move along were gone. Now there could be color and fonts and pictures. Using the metaphor of a desktop, the PARC engineers placed small, graphical representations of documents and file folders on the screen, and they built an external, hand-operated pointing device—called a mouse, since that was sort of what it looked like—to navigate the desktop by pointing and clicking to open and close documents and perform other functions.

When Steve Jobs saw all this demonstrated at the PARC labs, he instantly recognized that PARC’s bit-mapped, graphical interface was the key to making a computer user’s experience nontechnical, simple, fun, and intuitive. Do this, he knew, and it would realign the personal computer universe. “It was like a veil being lifted from my eyes,” Jobs told Isaacson. “I could see what the future of computing was destined to be.”

What Jobs could not see was his own future at the company he’d cofounded. A year after the Macintosh was released, Jobs was ousted from Apple. He cashed out his stock options, walked away with about $100 million, and cast about for something to do. Eventually, he made two investments. One was to found a new, high-concept computer company called NeXT. The other was to buy a small computer animation studio being sold off by the filmmaker George Lucas.

Apple, meanwhile, was foundering. Jobs’s guiding philosophy—that to maximize the user experience it was necessary to control both hardware and software—had led to superior products, but it was out of sync with the marketplace, which wanted cheaper and faster, even if cheaper and faster were unattractive and unwieldy. Microsoft’s CEO Bill Gates understood this and licensed his company’s operating system, MS–DOS, to any number of hardware manufactures, IBM among them, and before long both IBM and Microsoft came to dominate the personal computer world.

With Jobs gone from Apple, the new leadership tried to have it both ways, continuing to sell Apple’s own branded, closed, hardware-software systems like the Mac, while also licensing the Apple operating system to clone makers, but this only served to cannibalize hardware sales. By 1996, Apple’s share of the PC market had dropped from 16 percent to 4 percent, and the company was being written off in the business press.

As Apple was falling apart, Steve Jobs’s two investments were not doing so well, either. His computer company, NeXT, aimed to build affordable, Mac-like workstations powerful enough to be used by universities and other research institutions. Mac-like meant stylish and intuitive. Powerful enough meant having sufficient computing power to perform high-level functions. A small cadre of software engineers, some of whom had come from Apple (prompting a lawsuit), set about developing a new operating system based on UNIX, which had come out of Bell Labs in the late 1960s and was the first operating system that was not machine-dependent. While they did this, Jobs turned his attention to NeXT’s design, which he envisioned as a perfect cube. According to Isaacson, the near impossibility of constructing a perfect cube resulted in outrageous costs, like a $150,000 specially designed sander to round off rough edges, and molds to make the sides that cost $650,000 each.

Though Jobs’s intent with NeXT was to create an affordable research computer, by the time it launched, the NeXT cube cost $6,500, and needed a $2,000 printer and a $2,500 external hard drive because the optical drive Jobs had insisted upon was so slow. At that price, no one was buying. Instead of the ten thousand units the company estimated shipping each month, the number was closer to four hundred. As Isaacson points out, the company was hemorrhaging cash.

It was the same for Jobs’s computer animation studio, which kept needing infusions of money to stay in business. If he could have found a buyer, he would have unloaded it. Instead, he poured $50 million into it—half of what he had made selling his Apple stock. Almost as an afterthought, the company’s animators made a short film as a sales device to show off its unique hardware and software package, which cost well over $120,000. Remarkably, the film was nominated for an Academy Award. This led to other short films, one of which, Tin Toy, did win an Oscar in 1989, and to a deal with Disney for a full-length computer-animated feature film. Released at the end of 1995, Toy Story was the top-grossing film of the year. Betting on the film’s success, Jobs had arranged for the company, which had taken the name Pixar, to go public the week after the movie opened. By the end of the first day of trading, Jobs’s stake in Pixar was worth $1.2 billion.

Then, in an even more unlikely turn of events, Jobs’s investment in NeXT also paid off, less in money—though that would eventually come in the form of significant stock options—but in something more valuable: vindication. Apple, which looked to be close to dissolution, made a deal with Jobs to buy NeXT’s operating system, and he came along with it. Eleven years after his ouster, Jobs was back at the company he’d founded.

The next part of the Steve Jobs story—call it act three—is the one that we are most familiar with because it coincides with a key flashpoint in the lives of even those without the means or desire to buy Apple products: the metastatic growth of the Internet. Jobs was prescient in understanding how deeply the Internet could reach into our lives, and that it was not limited just to networking computers. Once the iPod came out, then the iTunes store, then the iPhone, then the App Store, then Apple TV, then the iPad, and the iBookstore, and now iCloud, Jobs and his team at Apple had created an entire, expanding, ensnaring iUniverse. (And now Siri, the recently released natural-language-processing “personal assistant” built into the iPhone 4S, has the potential to contract the competing universe created by Google since it will send fewer and fewer queries through Google’s search engine, which is the core of Google’s business.)

Jobs’s original premise, that Apple needed to manage the user experience by controlling both hardware and software—the premise that nearly destroyed the company in the 1980s and 1990s—was still his guiding philosophy. But this time around it catapulted Apple from niche brand to mass-market phenomenon—in part because once consumers entered the iUniverse there were costs associated with leaving it, and because Jobs made sure it was a pleasant place to be. And even though it became a mass-market brand, it retained its cachet.

The coolness factor set Apple apart from the start. Jobs’s Zen aesthetic (he was a longtime student of Buddhism), his passion for design, his good fortune to hire Jony Ive, who must be the finest industrial designer working today, and his other guiding philosophy—that function should not dictate form but, rather, form and function are integral and symbiotic—resulted in unique-looking products that, almost without exception, worked more smoothly than anyone else’s. And just in case that was not enough incentive for consumers to part with their money, Jobs transformed the product launch into a theatrical production, building suspense in the months and weeks beforehand with leaks and rumors about “revolutionary” and “magical” features, and then renting out large auditoriums, orchestrating the event down to its smallest detail, and, on launch day, holding forth, typically on an empty stage, in his blue jeans and black turtleneck, using the words “revolutionary” and “magical” some more. The original Mac launch took place shortly after a chilling, Ridley Scott–directed ad suggesting that anyone who used an IBM PC was a drone, while Mac users were people who defy conformity, aired during the 1984 Super Bowl, and has become the model for every Apple product launch since:

The television ad and the frenzy of press preview stories were the first two components in what would become the Steve Jobs playbook for making the introduction of a new product seem like an epochal moment in world history. The third component was the public unveiling of the product itself, amid fanfare and flourishes, in front of an audience of adoring faithful mixed with journalists who were primed to be swept up in the excitement.

(It should be noted that Apple product launches are now live-blogged in The New York Times and other major newspapers as if they were sporting events or breaking news.) Jobs was so good at this show-and-tell that it did not feel like he was on the stage selling but, rather, that he was up there offering, and what he was offering was the chance to share in the magic. Who wouldn’t want in?

As others have before him, Isaacson writes about what those who worked with Steve Jobs called his “reality distortion field”—Jobs’s belief that rules did not apply to him, and that the truth was his to create. “In his presence, reality is malleable. He can convince anyone of practically anything,” an Apple colleague told Isaacson. What this meant in practice was that when Jobs told Apple employees that they could do things that had never before been done, like shrinking circuit boards or writing a particular piece of code or extending battery life, they rose to the occasion, often at great personal cost. “It didn’t matter if he was serving purple Kool-Aid,” another employee said. “You drank it.”

And so, in many ways, have most of us, and not just by buying what Steve Jobs was selling—the products and the feeling of being a better (smarter, hipper, more creative) person because of them. Through his enchanting theatrics, exquisite marketing, and seductive packaging, Jobs was able to convince millions of people all over the world that the provenance of Apple devices was magical, too. Machina ex deo. How else to explain their popularity despite the fact that they actually come from places that do not make us better people for owning them, the factories in China where more than a dozen young workers have committed suicide, some by jumping; where workers must now sign a pledge stating that they will not try to kill themselves but if they do, their families will not seek damages; where three people died and fifteen were injured when dust exploded; where 137 people exposed to a toxic chemical suffered nerve damage; where Apple offers injured workers no recompense; where workers, some as young as thirteen, according to an article in The New York Times, typically put in seventy-two-hour weeks, sometimes more, with minimal compensation, few breaks, and little food, to satisfy the overwhelming demand generated by the theatrics, the marketing, the packaging, the consummate engineering, and the herd instinct; and where, it goes without saying, the people who make all this cannot afford to buy it?

While it may be convenient to suppose that Apple is no different than any other company doing business in China—which is as fine a textbook example of a logical fallacy as there is—in reality, it is worse. According to a study reported by Bloomberg News last January, Apple ranked at the very bottom of twenty-nine global tech firms “in terms of responsiveness and transparency to health and environmental concerns in China.” Yet walking into the Foxconn factory, where people routinely work six days a week, from early in the morning till late at night standing in enforced silence, Steve Jobs might have entered his biggest reality distortion field of all. “You go into this place and it’s a factory but, my gosh, they’ve got restaurants and movie theaters and hospitals and swimming pools,” he said after being queried by reporters about working conditions there shortly after a spate of suicides. “For a factory, it’s pretty nice.”

Steve Jobs cried a lot. This is one of the salient facts about his subject that Isaacson reveals, and it is salient not because it shows Jobs’s emotional depth, but because it is an example of his stunted character. Steve Jobs cried when he didn’t get his own way. He was a bully, a dissembler, a cheapskate, a deadbeat dad, a manipulator, and sometimes he was very nice. Isaacson does not shy away from any of this, and the trouble is that Jobs comes across as such a repellent man, cruel even to his best friend Steve Wozniak, derisive of almost everyone, ruthless to people who thought they were his friends, indifferent to his daughters, that the book is often hard to read. Friends and former friends speculate that his bad behavior was a consequence of being put up for adoption at birth. A former girlfriend, who went on to work in the mental health field, thought he had Narcissistic Personality Disorder. John Sculley, who orchestrated Jobs’s expulsion from Apple, wondered if he was bipolar. Jobs himself dismissed his excesses with a single word: artist. Artists, he seemed to believe, got a pass on bad behavior. Isaacson seems to think so, too, proving that it is possible to write a hagiography even while exposing the worst in a person.

The designation of someone as an artist, like the designation of someone as a genius, is elastic, and anyone can claim it for himself or herself and for each other. There is no doubt that the products Steve Jobs brilliantly conceived of and oversaw at Apple were elegant and beautiful, but they were, in the end, products. Artists, typically, aim to put something of enduring beauty into the world; consumer electronics companies aim to sell a lot of gadgets, manufacturing desire for this year’s model in the hope that people will discard last year’s.

The day before Jobs died, Apple launched the fifth iteration of the iPhone, the 4S, and four million were sold in the first few days. Next year will bring the iPhone 5, and a new MacBook, and more iPods and iMacs. What this means is that somewhere in the third world, poor people are picking through heaps of electronic waste in an effort to recover bits of gold and other metals and maybe make a dollar or two. Piled high and toxic, it is leaking poisons and carcinogens like lead, cadmium, and mercury that leach into their skin, the ground, the air, the water. Such may be the longest-lasting legacy of Steve Jobs’s art.

This Issue

January 12, 2012

Do the Classics Have a Future?

Convenience

Republicans for Revolution