Frank Rich

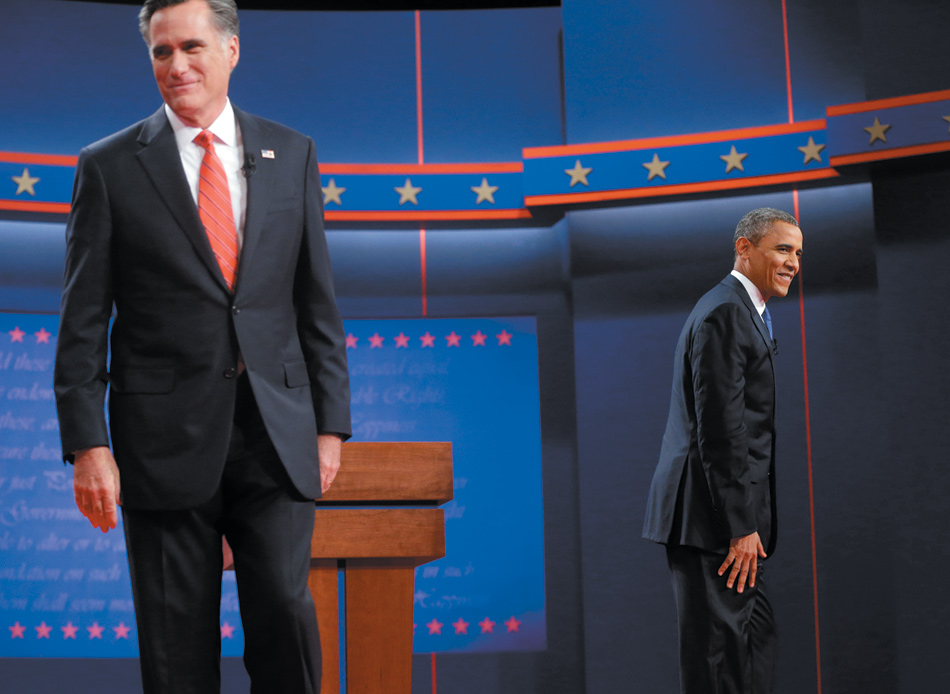

For all the liberal nail-biting about the presidential campaign of 2012, and for all the entertaining journalistic updates on the daily horse race, the fundamental story has remained unchanged (and not terribly suspenseful) all year. The Republican Party’s angry and highly motivated conservative base—possessed by loathing of Barack Obama and his devious schemes to turn America into Sweden—could not find a plausible candidate to lead its crusade. Assuming that Obama retrieves the A game he failed to bring to his convention address and first debate, the right now faces the serious prospect of defeat in what it saw as a can’t-miss election in which a sluggish economic recovery, a much-vilified health care law, and the public’s presumed disenchantment with an incompetent president were all supposed to guarantee victory.

The first draft of history, especially as written by Charles Krauthammer, Peggy Noonan, and their fellow travelers at Fox News, may well tell us that it was all Mitt Romney’s fault. Such an oversimplification would be designed to bury their own embarrassing record of getting behind a nominee whose career-long penchant for political malpractice has not exactly been a state secret. Still, Romney’s early dreadfulness as a candidate was breathtaking. For a while he had the highest negative poll ratings of any major-party presidential nominee in modern polling history. He has no fixed principles, and seemingly no fixed abode. (Can anyone say with authority whether his principal home is in New Hampshire, California, or Massachusetts?) For its part, his campaign has had no compass either, veering off at the slightest distraction from its stated strategy (a laser focus on the unemployment rate and Obama’s failure to ameliorate it).

As a retail campaigner, Romney’s human skills fall somewhere between those of Richard Nixon and Hal the computer in 2001: A Space Odyssey. He does not know how to speak American English (e.g., “sport” for “sports”). And he has remained a mystery man to voters no matter what the full-press efforts to “humanize” him. That’s because three of the four main planks of his biography (his career in equity capital at Bain, his moderate tenure as governor of Massachusetts, and his lifelong devotion to the Church of Latter-Day Saints) were skirted whenever possible by Romney and his handlers out of fear that the details could scare away various sectors of his own base, whether white working-class men, anti-Obamacare zealots, or evangelical Christians. The fourth item on the Romney résumé, his performance in “saving” the 2002 Winter Olympics, was muddied by the candidate when he kicked off his tour abroad by insulting Britain’s conservative leadership on its management of what would prove to be a stellar Summer Olympics in London.

What’s now half-forgotten in the pileup of Romney’s campaign debacles is just how vehemently voters in his own party have always disliked him and still do. For much of the Republican primary contest, somewhere between three quarters and two thirds of the GOP electorate wanted anyone but Romney, with the bar for “anyone” at times sinking low enough to let in clowns as manifestly unfit for the presidency as Donald Trump and Herman Cain, neither of whom had ever held public office of any kind.

Both before and after Romney secured the nomination by default, he was tireless in pandering to the various GOP constituencies who kept rejecting him. He called for the “self- deportation” of illegal immigrants and vowed to stop funding for Planned Parenthood and Title X. He chose an Ayn Rand disciple as a running mate. He cracked a birther joke. He mouthed a truculent foreign policy under the tutelage of unreconstructed Bush administration neocons. He fully embraced the chimera of supply-side economics to the embarrassing point, especially for a professed data guy, of leaving the numbers blank in his campaign’s tax and budgetary policy proposals.

And yet with the sole (and far from representative) exception of Fox News, many in the conservative camp remained not just skeptical but outright hostile. The critique of the Republican standard-bearer from the right was just as harsh as that from Democrats—and not just because of his botched campaign. During the Republican convention Romney was frequently lacerated on ideological grounds by the popular right-wing radio talk-show hosts Glenn Beck, Michael Savage, Mark Levin, and, on occasion, Rush Limbaugh. Foreign policy analysts at The American Conservative routinely mock Romney’s neocon retinue and his reckless saber-rattling at Iran. When Romney was caught on video in what seemed to be a sincere John Galtish monologue bemoaning the “47 percent” of Americans who are government-dependent deadbeats, the Wall Street Journal editorial page and other true believers criticized Romney not for the political disaster of alienating half the voting public but for not articulating the conservative economic catechism as brilliantly as Journal editorialists.*

Advertisement

Romney is so distrusted and disdained by the mainstream of his own radical right-wing party that in the event he enters the White House, he will serve as a pliant errand boy for the elements in the base he tried and failed to placate throughout the campaign. Grover Norquist spoke for the real powers-that-be in the GOP when he told the Conservative Political Action Committee in February that the GOP candidate’s only function as president would be “to sign the legislation that has already been prepared” by the Republican congressional caucus, starting with the government-slashing Ryan budget.

If Romney loses, he will retreat into whatever state he resides in, fading immediately into oblivion. Historians will forever wonder how a man with no constituency in either political party ever ascended to the top of a national ticket. Romney is but a placeholder in the rightward evolution of the GOP, and his candidacy has been nothing if not a genuine fluke, unlikely to be repeated anytime soon. In his wake, the right will move fast to identify the tribune it has been yearning for, someone like Paul Ryan or Marco Rubio who can give voice to its ideology and rage without frightening swing voters (no Bachmann or Santorum need apply) and who will at last offer the country the uncompromising alternative to Democratic fecklessness that was missing from the top, if not the bottom, of the GOP ticket in 2008 and 2012.

Though the last presidential race and this one have been routinely called “historic” by one side or the other, both elections may yet prove footnotes en route to the showdown that’s in store for our polarized nation in 2016.

David Cole

The one thing this election is not likely to turn on is national security and human rights. Other concerns have dominated the campaign, including the economy, the increasing divide between the wealthy one percent and everyone else, and the responsibilities of government to provide for basic needs such as health care and Social Security. The facts that there has not been a major terrorist attack in the United States since 2001, Osama bin Laden is dead, and many of al-Qaeda’s leaders have been killed or captured have both reduced the salience of terrorism and buttressed President Obama’s credibility. Polls report that more Americans trust President Obama to keep us safe than Mitt Romney.

But while the election is unlikely to turn on national security and human rights, the corollary is not true; national security and human rights almost certainly would be deeply affected by the election results. A Romney administration would risk a return to the immoral, illegal, and counterproductive policies of President George W. Bush. We were painfully reminded of this prospect on September 27, when The New York Times reported on a leaked memo, written by Romney’s national security advisers, urging him to advocate restoration of the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation techniques,” i.e., to return us to the “dark side” of professionally administered torture and physical cruelty.

Romney did not write the memo himself, of course, and we do not know precisely how he reacted to it. But it is consistent with his public statements, in which he has criticized President Obama for ending the “enhanced interrogation techniques,” and has maintained, against precedent and common sense, that waterboarding is not torture.

The Romney torture memo is unsigned, but was written by members of a committee of Romney national security advisers that included Steven Bradbury, Cully Stimson, David Rivkin, and Lee Casey. These may not be household names, but they should cause alarm among those who care about the United States’ commitment to the rule of law. Bradbury, as head of the Office of Legal Counsel under Bush, wrote several secret memos in 2005 and 2007 arguing that the CIA’s abusive interrogation practices were not only not torture, but were not cruel, inhuman, or degrading, and did not violate the Geneva Conventions ban on humiliating treatment of detainees. Under these strained arguments, the tactics—which included forced nudity, prolonged sleep deprivation, slamming suspects into walls, painful stress positions, and waterboarding—would be entirely legal if employed against our troops by foreign nations, and would be constitutional even if used against suspects arrested here at home.

John Yoo and Jay Bybee, who wrote the first memos authorizing the CIA program in August 2002, have taken the brunt of public criticism for giving legal cover to patently illegal conduct, but in many ways Bradbury’s memos are even more disturbing. They came years after the fear of the initial 2001 attacks had subsided, and after Congress and the Supreme Court had explicitly rejected administration efforts to avoid the prohibitions on detainee mistreatment. Moreover, Bradbury’s memos ignored an internal CIA investigation that found that the tactics had been regularly abused, had resulted in no information that disrupted any ongoing attacks or “ticking time bombs,” and could not be shown to have obtained any information that could not have been gained through lawful interrogation measures. President Obama rescinded the secret Bradbury memos, and made them public, saying he did so “to ensure that the actions described within them never take place again.” But apparently Bradbury has not given up, and Romney appears to have accepted the gist of his deeply flawed advice.

Advertisement

Romney’s other advisers are just as bad. Cully Stimson is the former Pentagon detainee chief who infamously urged corporate clients to boycott the large law firms that had dared to represent, pro bono, Guantánamo detainees. And Rivkin and Casey, former Reagan administration officials, served throughout the Bush administration as reflexive defenders in Op-Ed pages of every human rights violation the Bush administration committed, including torture, extraordinary rendition, disappearances, and warrantless wiretapping. If these are the people to whom Romney is listening, his election would in all likelihood portend a repetition of the government’s worst post–September 11 mistakes.

Of course, President Obama has not exactly been a beacon of light on such critical rule-of-law issues as transparency and accountability. He has opposed all attempts to assign responsibility for the war crimes committed in the name of the US, including even apologies to the victims, and a public commission that might draw lessons for future policy. He has regularly exercised a secret power to kill suspected terrorists, including US citizens, with remote-controlled drones far from any battlefield, and has refused to disclose all but the most vague parameters of that awesome power. He has sought to block judicial review of many of the government’s most dubious tactics, including the drone program, the sweeping wiretapping of Americans’ international phone calls, and renditions to torture.

Still, as the latest “torture memo” illustrates, President Romney would be far worse. And President Obama deserves credit for closing the CIA’s secret prisons, ending torture, abandoning President Bush’s assertions of unchecked presidential power, and insisting that the struggle against terrorism must be fought within the confines of the rule of law—including both constitutional and international law. Those reforms have made us, from all evidence, more safe, not less, while denying al-Qaeda the anti-US recruitment propaganda that President Bush delivered as if on orders from his adversary.

Will President Obama in a second term make progress on some of the issues on which he has been stymied by congressional opposition, such as the closure of Guantánamo and the trial of terrorists in civilian criminal court? A president concerned less about reelection and more about his historical legacy might well do more to restore the rule of law, and certainly more needs to be done. But one thing should be clear—that’s the question we want to be asking come November, and not what torture tactics Steven Bradbury will be advising President Mitt Romney to authorize behind closed doors.

Ronald Dworkin

Every four years liberals and conservatives declare the coming presidential election the most important in decades. And every four years, in recent years, they have been right. This election is even more critical than the last one because the Republican Party has suddenly bolted to a new and radical right-wing extreme. Its Tea Party platform shows an obtuse commitment to the economic strategies that produced disaster in 2008 and shameless disdain for poor people and for minorities of every kind.

Except the very rich: the Tea Party, and Romney—before the fudging during the first debate—promised to lower taxes for them and nevertheless to reduce the federal deficit through an unnamed and mysterious policy of closing loopholes. In fact such tax cuts would either require savage spending cuts on already pared-down welfare programs for the poor and on desperately needed infrastructure repair or—equally likely—force a frightening increase in the already dangerous national debt. The election of Mitt Romney and a Republican Congress could well be a catastrophe for both economic stability and social justice.

The catastrophe might very likely be prolonged, for decades, by Romney appointments to the Supreme Court. Four of the Court’s nine justices—including two of its four moderates—are well into their seventies, and the odds that the next president will have a dramatic and enduring effect on the Court’s composition are strong, particularly if, following established Republican tradition, he appoints justices young enough to stay in power long after the political climate that produced their appointments has disappeared.

The great danger of a strengthened radical right-wing court is sufficiently demonstrated by the rain of legally indefensible and politically retrograde 5–4 decisions in recent years, including Bush v. Gore, which cursed us with George W. Bush, Gonzales v. Carhart, which sustained a cruel federal law outlawing “partial-birth” abortions, Seattle School District and Jefferson County Board of Education, which overturned voluntary, modest, and effective programs aimed at increasing racial diversity in public schools, and the infamous Citizens United ruling that corporations have all the First Amendment rights of real people so that they have an unlimited right to spend their corporate treasuries on television ads opposing candidates whose policies they think against their financial interest.

The deeply corrosive impact of that last decision is already apparent in this election. As The New York Times reported:

This is the first presidential election since the Supreme Court’s decision in the Citizens United case removed the last barriers to campaign spending by corporations and other groups. Analysts are bracing for a tidal wave of money from rich individuals, companies and labor unions that could alter the political landscape and transform American democracy.1

Much of this money comes from groups called Super PACs, which are subject to no restrictions except that they must act independently of the parties’ official campaigns. It is not plain that Romney will raise more money from Super PACs than Obama in this election. Priorities USA, the main group supporting Obama, raised $10 million in August, compared to $7 million by Restore Our Future, the main pro-Romney group, though the latter group had raised much more money earlier. That hardly diminishes the danger to democracy of large and often undisclosed corporate gifts.

The Citizens United decision was plainly wrong in constitutional principle; there is no even remotely plausible interpretation of the First Amendment that justifies it.2 Some commentators declared, when the decision was announced, that though it was wrong as a matter of constitutional law, it would cause little damage because corporations would be wary of taking political positions that might anger some of their consumers.

That sanguine prediction is no longer plausible, as the size of corporate contributions in this election has already shown, partly because corporations and megarich individuals have found a way to give to Super PACs without disclosing their identities. They give to nonprofit institutions that are allowed to contribute to Super PACs without reporting where their own money comes from. Democrats in Congress tried to change the law to require these institutions to disclose the sources of their contributions, but Republicans blocked the change. The US Chamber of Commerce opposed disclosure for exactly the reason that was supposed to limit corporate contributions. Disclosure, it said, could open corporations to “retaliation against unpopular or unfavorable political views, which also infringes constitutional rights.”3 So careful corporations need not fear offending consumers after all.

It is therefore regrettable that the general public takes so little interest in the Supreme Court and that the Obama campaign consequently rarely mentions the issue. It seems impossible to interest the public in the issue. Chief Justice John Roberts’s surprising, apparently last-minute, decision to vote to sustain President Obama’s Affordable Care Act has contributed to the public apathy, and that might help to explain his decision.4 If he had joined the four other right-wing justices in striking down the act, Obama would almost certainly have campaigned against the decision, and perhaps made the Court’s power and politics the issue it should be, a result Roberts presumably wanted to avoid.

If the public had been engaged, it would have been warned about a further decision compromising democracy that the Roberts Court seems poised to make. It seems likely to declare unconstitutional crucial parts of the venerable Voting Rights Act of 1965. Section 5 of that act requires all or some counties in states that have a particularly egregious record of voter discrimination in the past—Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia—to obtain a “preclearance” from the Department of Justice or from a three-judge federal court before they change their voting laws in any way. The act was a celebrated civil rights victory when first adopted, and it has been reenacted by Congress several times since, most recently in 2006 when it was extended for twenty-five years by a large majority of both houses. It places the burden of proof on a covered state to show that any new law would not have the effect of disadvantaging minority voters.

Section 5 continues to be an important safeguard of electoral fairness. Since 2010, when the Republican Party greatly expanded its power in state governorships and legislatures, it has tried through a variety of means to minimize the electoral impact of citizens likely to vote Democratic or to prevent them from voting at all, and Section 5 has been crucial in blocking the most blatant of these attempts.

When Florida recently decided to reduce the number of early-voting days, which allow people to vote who cannot take time off on Election Day, it was barred from making the change in five counties covered by the preclearance requirement. So it simply exempted those counties from the change. The Department of Justice then objected to different election schedules in different counties and required Florida to negotiate a common voting schedule for the entire state. Freed of the requirements of Section 5, Florida would have had much greater latitude to curtail early voting.

When Texas was recently awarded four additional congressional seats, the state legislature drew the new boundaries so as to reduce the chances that Hispanics would have an impact on elections in mixed districts. The plan was blocked by Section 5: neither the Department of Justice nor a federal court would grant the preclearance the act required. A three-judge federal panel said, unanimously, that the evidence left no doubt that the plan was designed to reduce the overall voting power of Hispanics in the state.

Since 2010, several states (all but one with Republican governors) have enacted laws that require voters to present official identification cards, in many cases with a photo, at the voting booth. The most common ID is a driver’s license; people who do not have one are mostly poor and disproportionately black or Hispanic. Such citizens can obtain substitute ID cards in those eleven states but only after burdensome and in some cases expensive application, often requiring applicants to travel a considerable distance to official card-dispensing offices.

The antidemocratic intent of voter ID laws has barely been disguised. A Pennsylvania Republican official openly declared that that state’s new ID law would help ensure that Romney carried the state.5 Governor Rick Perry of Texas rushed through a particularly strict ID law as “emergency” legislation, bypassing established procedures to ensure that the law would be in place for the coming election. Perry’s law provided that gun permits, among other official certificates, would be acceptable ID cards but that student registration cards would not.

When Republicans defend voter ID laws at all, they claim them necessary to prevent voter impersonation fraud. But there are extremely few documented cases of such fraud in recent years. Pennsylvania, when its law was challenged in federal court, declared that it did not rest its case on any assumption that fraud was a serious problem,6 and an executive of the South Carolina Election Commission conceded, in court, that the new law would not prevent voter fraud.7

Courts have declared several voter ID laws illegal, or postponed their enforcement, after extensive litigation. But Republicans try to adopt such laws shortly before an election so that litigation cannot prevent their immediate use. A Pennsylvania judge refused to enjoin its ID law while it was being tested in the courts; it was finally denied immediate effect on October 2, only weeks before the presidential election. The Pennsylvania judge ruled that people could vote without ID cards, in this election, though they could—pointlessly—still be asked to produce one. The preclearance demanded by Section 5 provides, for the historically most racist states, a much more effective barrier. Texas’s statute could not go into effect without positive clearance, and voter ID laws were refused preclearance in South Carolina.

In the Texas case, a three-judge federal court declared, in a long and painstaking opinion by Judge David Tatel of the D.C. court, that the evidence Texas offered not only failed to prove that its law was not discriminatory, as the act required it to show, but positively proved the opposite: that the law was in fact thoroughly discriminatory.

However, Shelby County, Alabama, which is covered by Section 5, has now asked the Supreme Court to declare Section 5 unconstitutional, and it has been joined by the attorneys general of five states. They were all but invited to sue by Roberts, who, in a related 2009 case, went out of his way to suggest that he thought Section 5 unconstitutional, and that he would vote to strike it down if asked to do so. “Things have changed in the South,” he said. “Voter turnout and registration rates now approach parity. Blatantly discriminatory evasions of federal decrees are rare. And minority candidates hold office at unprecedented levels.”

Justice Clarence Thomas, speaking for himself, was even clearer: “I conclude,” he said, “that the lack of current evidence of intentional discrimination with respect to voting renders Section 5 unconstitutional.” It seems likely that the rest of the right-wing justices will follow this lead and agree to strike down the preclearance requirement, perhaps in yet another 5–4 decision.

Roberts’s statement was curious. He summarily contradicted Congress on a complex judgment of fact, in spite of the extensive record of continuing discrimination that Congress compiled in renewing the Voting Rights Act in 2006, and in spite of the large majorities that voted for renewal. The recent Texas examples alone, in which obviously discriminatory redistricting plans and voter ID laws were blocked by the preclearance requirement, would seem to indicate that Congress had at least a substantial basis for its decision.

In any case, the coming Supreme Court ruling will be yet another decision testing the integrity of our democracy. From time to time, when a new justice is nominated and Senate hearings are held, the nation’s attention does shift, mildly, to constitutional issues. But these hearings are a sham: candidates say only that they believe in applying the law and senators duly nod approval.

Most politicians apparently assume that the character of the Supreme Court is too abstract an issue to figure in an election campaign. But FDR successfully campaigned against the “nine old men” who were blocking his New Deal, Nixon made the Court’s race decisions the center of his “southern strategy,” and generations of Republicans have been elected by denouncing the Court’s 1973 decision recognizing abortion rights. The record of the Roberts Court is already one of the worst in our history. In pursuing a right-wing agenda it has overruled many precedents. Next term it will probably not just strike down Section 5, but also overrule its own recent decision allowing limited affirmative action. It gives every sign of soon reversing abortion rights. Perhaps it is impossible to make independent voters alert to these dangers. If so, that is a shame.

Russell Baker

Having purged their ranks of liberals, moderates, and many ancient and honorable conservatives whose service antedated the Reagan era, Republicans have whittled themselves down to a reactionary party angry at the modern age, fearful of the future, and terrorized by the radical Tea Party. The Tea Party is not actually a party, of course, but a revolutionary movement of malcontents who seem to despise or fear the way the world is trending and to hold an older generation of Republicans responsible for it. Their response has been to eliminate Republicans whose conservatism they judge to be impure.

What they call conservatism seems a great deal like the sentimental longing for those mythic good old days with which depressed codgers belabor the young on long car trips. In Tea Party types it seems like nostalgia for a past when social security meant ending life in a poorhouse and health care meant knowing a doctor who made house calls. During the past five or six years old-line Republicans whose conservatism failed to meet the new purity standards have found themselves sandbagged in primary elections by cunning Tea Party minorities and replaced by Republicans of the new breed.

This development has been a mighty force in the restructuring of the Republican Party. Its influence is visible in this year’s party platform with its surly attitude toward women’s issues, its barely concealed hostility toward the burgeoning immigrant population, and its subliminal dream of repealing a hundred years of progressive government. The passion for turning back the calendar and revisiting the joys of keeping cool with Coolidge, if not the gloriously tax-free age of Mark Hanna and President McKinley, is not a passion, one suspects, that thrills Mitt Romney to his pragmatic Mormon roots. Indeed, the purified conservatism that now afflicts the Republican Party seems so alien to Romney’s personality, character, and history that his candidacy seems bizarre.

As evidenced by his performance in the first debate with President Obama, Romney clearly decided that—bizarre or not—his career as a devout right-winger was not working, and, ever the pliable politician with a corporate respect for the bottom line, he suddenly presented the public with a new face. This time he became the genial, reasonable business executive who was friend to all mankind, including the 47 percent he had earlier dismissed as moochers.

How long the party will put up with this latest Romney, even if it wins him the White House, is very much an open question. Everyone knows the Republicans didn’t really want him in the first place. As governor of Massachusetts he had been shamelessly moderate. Among other offenses, he had connived with Democrats to create the nation’s first state-run health care program. Worse, Barack Obama’s own health care program—the odious Obamacare, as Republicans christened it—was fashioned in likeness to Romney’s Massachusetts plan. This alone, one might suppose, would have sufficed to guarantee Romney’s expulsion from the party.

Republicans, however, were not so eager to expel a respectable-looking presidential wannabe after they surveyed the field. The nine who took the stage for the Republicans’ first televised debate reminded all America that ours is not a great age for producing statesmen. A pizza magnate led the early polls, Newt Gingrich appeared looking insufferably superior, then a slightly manic woman from Minnesota, and a defeated senator from Pennsylvania seeking another chance at the brass ring. Donald Trump hovered in the wings, a constant threat to turn everything into farce.

Through it all, debate after debate, month after month that began to feel like year after year, Mitt Romney endured. It gradually became clear that with so many Republicans having been chased out of the party, the only plausible candidate left was Romney. He was not really plausible to a great many Republicans, but he looked plausible. He wore a two-piece suit of conservative cut and wore it well. He could speak coherent sentences, and though he sometimes spoke foolishly he was never idiotic, or clownish, and though we knew he was richer than Croesus and loved money, he never looked as superior as Gingrich looked, and always uttered the foolish piffle and claptrap of politics as though he meant it.

The party must have realized quite early that it was going to have to nominate him. There was simply no one else who even seemed plausible. Many obviously hated him for being inescapable, but what could be done? He could never pass the conservative purity test, even after incessantly insisting that his Massachusetts health care bill had nothing in common—nothing at all, mind you!—with the odious Obamacare.

Everyone could see he was a faker and could accept that because he was such a transparent faker. It’s the polished faker who scares politicians, master fakers like Bill Clinton and Lyndon Johnson. Other politicians famous for cunning know that even they are going be outwitted by fakers of that quality. Nobody was fooled by Romney: he had been a moderate, maybe even close to liberal now and then, and now, declaring his lifelong devotion to conservatism, he was incapable of concealing the reality—that he had no ideology whatever, just a readiness to be whoever or whatever was necessary to become president.

To close the deal he had to accept the full conservative package. This was done symbolically with his choice of the outspoken right-wing congressman Paul Ryan as his vice-presidential candidate. Ryan is a man so obviously itching to throw away the whole twentieth century and a good bit of the twenty-first and get back to the good old days that he is walking certification of Romney’s desire to be an authentic mossback. Together they left the Republican convention sworn to fight hard for tax cuts for the super rich, repeal of the health care program, systematic dismantling of Medicare, and an end to regulations meant to curb profitable corporate abuses. The march backward might now at last begin.

As for President Obama, he is afflicted with the kind of economic letdown that usually means curtains for presidents. The Supreme Court, having developed a taste for presidential politics since it dropped the veil twelve years ago to make George W. Bush our president, has licensed everybody to spend limitless millions on the party of their choice. Since people with limitless millions naturally tend to be Republicans, the Court seems to have done the Grand Old Party another favor.

Moreover, Republicans’ congressional leaders have so brilliantly perfected the art of obstructing the president from doing anything to improve the economy that they are now able to denounce him as a failure who has not got anything done.

The Republicans have been ingenious in using the rickety old congressional legislative machinery as a weapon for destroying the Obama presidency. Historians may find it ironic that the filibuster, one of the major devices used to obstruct Obama’s program in the Senate, was developed originally to perpetuate the nation’s subjection of blacks for almost a hundred years after the Republican Lincoln proclaimed their emancipation.

Presumably Democrats would use it, too, should Romney become president.

-

*

For a detailed account of the conservative critique of Romney, see “My Embed in Red,” New York, September 16, 2012. ↩

-

1

Eduardo Porter, “Unleashing the Campaign Contributions of Corporations,” The New York Times, August 28, 2011. ↩

-

2

See my “The Decision That Threatens Democracy,” The New York Review, May 13, 2010. ↩

-

3

See US Chamber of Commerce, “Letter opposing the latest House and Senate version of the so-called DISCLOSE 2012 Act, S. 3369 and H.R. 4010,” July 12, 2012. ↩

-

4

See my “A Bigger Victory Than We Knew,” The New York Review, August 16, 2012. ↩

-

5

Annie-Rose Strasser, “Pennsylvania Republican: Voter ID Laws Are ‘Gonna Allow Governor Romney to Win,’” ThinkProgress, June 25, 2012. ↩

-

6

Nick Wing, “Pennsylvania Voter ID Law Trial Set to Begin as State Concedes It Has No Proof of In-Person Voter Fraud,” The Huffington Post, July 24, 2012. ↩

-

7

Luke Johnson, “Alan Clemmons, South Carolina Rep, Admits ‘Poorly Considered’ Reply to Racist Email on Voter ID Law,” The Huffington Post, August 29, 2012. ↩