Hilton Als is a theater critic for The New Yorker, but the two books he has written are not simply, or even primarily, works of criticism. His characteristic form is a kind of essay in which biography, memoir, and literary criticism flow into one another as if it were perfectly natural that they should. The pieces in his new book are about Truman Capote, Louise Brooks, Eminem, Flannery O’Connor, Michael Jackson, and Richard Pryor, among others, and leading the collection is an eighty-four-page personal essay about a romantic friendship that has shaped the last thirty years of Als’s own life and work.

In all of his essays, the life gets as much scrutiny as the work, with an eye to one particular question: How do artists come alive to their ambitions and then proceed to realize them? How does the work get made?

Sometimes it doesn’t. Als’s first book, The Women (1996), is about three people who, out of some combination of necessity and temperament, channeled most of their artistic impulses into the creation of their lives rather than their work. He writes about Dorothy Dean, the black Radcliffe and Harvard graduate whose primary career was social: she was a hostess and “unofficial mascot” to many members of New York’s gay, white male cultural elite of the 1960s and 1970s; and Owen Dodson, his mentor and lover, a playwright who was a minor figure in the Harlem Renaissance but, by the time Als met him, “preferred literary society to writing.”

But Als’s most remarkable subject in The Women is his mother, who emigrated from Barbados to New York at seventeen, worked as a housekeeper, a hairdresser, and an assistant at a nursery school, and raised “six children whom she cared for, more often than not lovingly, though she remained unconvinced that having children was the solution to the issue of isolation.” His mother had a thirty-year-long relationship with a man, Als’s father, whom she refused to marry. “She is so interesting to me—as a kind of living literature. I still envy her allure.”

Alluring is just what she is in this essay: her free and frequent exercise of skepticism, her refusal of euphemism and sanctimony on subjects such as marriage and children, her sensibility regarding books and movies, her support of Als’s childhood ambition to be a writer—all of these are part of her glamour, and part of the strange and original glamour of Als’s world on the page.

Perhaps Als and his siblings were a kind of living literature to their mother too; Als writes that one of her reasons for having children was “her curiosity about how lives get lived.” But she herself did not write. When the relationship with his father ended, she became depressed and was often bed-ridden with a series of maladies whose main physical cause was diabetes. “I think my mother’s long and public illness was the only thing she ever felt she experienced as an accomplishment separate from other people.”

Als, who realizes as a child that he is gay, identifies strongly with the women in his family (his mother as well as his older sisters), but as he grows up he begins to distinguish himself from them by steadily pursuing his ambition: he writes, and with the help of his mother he meets adults who steer him toward a literary education. He describes his mother’s and sisters’ envy as he comes under the influence of people outside the family: “They could not see me as a boy but only as a teenage girl—as their younger girl-selves, in effect. If I did not submit to their view of me, I would become part of the world they hated. I would become a man, replete with a narrative they could not access.” Als’s maleness was presumably not the main reason that he, and not his mother or sisters, became a published writer, but it was not entirely incidental either. What does sex, or race, or any other circumstance of birth have to do with a person’s fate? It’s a question Als often revisits.

The new collection, White Girls, is about people who made it. Richard Pryor, Flannery O’Connor, Michael Jackson, Vogue editor André Leon Talley, Eminem—they’ve had about as much success and fame as a person could reasonably hope for. Most of them achieved it against considerable odds. All of these artists engage in flights of imagination across racial and gender lines, and also get called back, sometimes brutally, to their actual bodies by the expectations and assumptions of other people.

White Girls is looser in conception than Als’s first book (some of the essays have been published in magazines), but in one way or another most of the pieces take up the subject of interracial relationships, especially affinities between black men and white women. “Tristes Tropiques” is a kind of maximalist personal essay about Als’s relationship with a friend whom he calls “Sir or Lady—or SL.” The men are not lovers, but “friendship” does not seem an adequate term for their closeness: “In the three decades or more since [SL] and I have been friends,” Als writes, “I have felt myself becoming him.” Als is gay, SL is straight. Als is in love with SL, and though his feelings are not entirely reciprocated, he thinks of them as a kind of couple. They met in the early 1980s, when Als was in his early twenties and they both worked at The Village Voice. SL is a photographer and filmmaker, a self-styled dandy, a fan of movies with romantic plots. When we first meet him he is describing the details of a movie love story while Als listens rapt: “I…look for myself in every word of it.”

Advertisement

Als and SL, who are black, are both interested in white women, real and fictional. This shared interest is one of the things that brings them together, and later pulls them apart. White women seem to be the only kind that SL goes out with. Als forms passionate friendships with some of SL’s white girlfriends, friendships that are often unstable, undone by envy and resentment on both sides.

But this is to start in the middle. When Als was a child growing up in East New York and Crown Heights, he would go to the Brooklyn Public Library not only to read but to “listen to recordings by grand actors reading famous poetry, prose, and plays.”

I listen to white girls such as Glenda Jackson as Charlotte Corday in Peter Weiss’s play Marat/Sade, because she is not genteel or cute in the role of the knife-wielding anarchist: she is a gorgeous hysteric…. She contradicts my family for me.

In high school Als had his first “direct experience with white people.” Among those whites, Marie:

She wasn’t technically white—her mother was Puerto Rican and her father Jewish—but she looked the part: camellia-white skin and blonde hair….

The Puerto Rican and Dominican men who leaned against their cars that lined the avenue in front of her apartment building, listening to merengue, to salsa, to Latin disco, waited for her to walk by so they could make rude comments in Spanish as she passed. And those same men fake fainted against their cars when she said, flashing her flat Jewish ass, something equally rude in boriqua Spanish. Did I love her or want to be her? Is there a difference?

Meanwhile, SL, who read a lot as a teenager, discovered an interest in the mostly white, second-wave feminist movement of the Seventies. He

began to hear bits of himself not in Piri Thomas or Eldridge Cleaver but in Shulamith Firestone, and Ti-Grace Atkinson, and Carolee Schneemann, and Robin Morgan: women who were of SL’s class, more or less, and had experienced, growing up, something akin to what he had known at the hands of a father: being subject to emotional violence because they owned you, you were their property.

He improbably ends up joining, for some unspecified amount of time, a lesbian separatist community on a farm in upstate New York. (“He planted burdock, and ate cold griddle cakes, and read Our Bodies, Ourselves.”)

“Tristes Tropiques” is an elegy for Al’s relationship with SL, which eventually came to a painful end. But there’s a second relationship being mourned in the essay. For a decade beginning in college, Als had a boyfriend whom he calls K. According to Als’s taxonomy, K was another of his “white girls,” a term loose enough to accommodate white boys as well. K died of AIDS in 1992. The peculiar platonic attachment between Als and SL, we learn, was in part a reaction to the deranging loss of K; it was a way to love and be loved without going all the way. Over the course of their friendship, SL would often be seeing and living with women, while Als lived alone in a crummy apartment that he calls “a stage set.”

I rarely had guests. How can you host in a theater? But if you looked behind the flats where, variously, my double bed had been sketched, along with a tea cup, shower curtains, and a stove, you’d find the same dull isolated crud you’d see in any number of apartments occupied by men who could not move on from AIDS. In any case, moving on was a ridiculous phrase, given the enormous physical memory of your loved one being stuffed in a black garbage bag; that’s how the city’s health-care workers dealt with the first AIDS victims, stuck them in garbage bags like imperfect pieces of couture….

In any case, “moving on” was a ridiculous phrase in this context, as was the trite idea of closure, and yet I was supposed to be alive, moving on, and what was that? Sometimes I moved on to a few boys who looked like the trashed and bagged loved one—especially around the eyes and feet—but they didn’t lie on my stage set’s double bed without getting paid: actors for hire.

One way that Als conveys his vulnerability is through such precise modulations between scorching wit (“the trashed and bagged loved one”) and the sense of raw emotion (“I was supposed to be alive, moving on, and what was that?”). Another aspect of his vulnerability is the strangeness of the relationship with SL itself. A thirty-year-long obsessive romantic-yet-platonic friendship? In claiming it as a form of couplehood, Als accounts for more human complexity in romantic relationships than we usually acknowledge.

Advertisement

One thing that all of the subjects in White Girls have in common is their flagrant failure at long-term marriage-like relationships. There’s Richard Pryor and his seven wives, Eminem and the bitter divorce he has examined so volubly in his songs, Flannery O’Connor’s apparently lifelong celibacy, the tortured love life, if that’s the term, of Michael Jackson. They seem movingly vulnerable in their aloneness, without the cover of privacy granted by a marriage. Of course long-term, public couplehood, to say nothing of marriage, was a less likely prospect for a gay man before Stonewall (like Capote), and might have involved too many sacrifices for a woman writer in the South in the 1950s (like O’Connor).

Still, whatever their generation, these characters taken together seem to speak to our contemporary predicament: how embarrassing to admit that one has not been able to find a mate in a supposedly egalitarian, sexually liberated, post-Stonewall era so abundant in sexual and romantic possibilities. Yet aloneness is exactly the hazard of being left so much to our own devices—i.e., our own object choices—when it comes to romance.

But to quote the above paragraphs about K is to give a sense only of the essay’s tighter and more conventionally turned passages. The thing about “Tristes Tropiques” is that it’s loose, and one of the effects of the essay is to suggest an unembarrassed self-absorption that most first-person essayists are at pains to deny. This sounds bad but Als has a surprising ability to make it good. “Tristes Tropiques” is a dense, absorbing piece whose atmosphere is stimulating and permissive. Als will seem to be breaking some essential rule of first-person essay-writing in disastrous fashion and then turn the passage inside-out, revealing it to have a different rhetorical function than you originally thought.

Listen to Als on the white women that SL goes out with. He starts out in a mode of arch high-mindedness: “Since I have always preferred to live in the next generation of hope, it was the children of those art-world ladies who worried me.” Oh? Say more?

Living in their male-identified world of having it all, the mothers who toiled in the corridors of photography and literature and the like couldn’t be bothered with feminism because what is feminism but humanism; they didn’t want their children—particularly their girl children—to make the mistake they’d made at Brown or Yale or Berkeley or whatever, which is to say believing feminism and thus humanism had any value at all, and would get them anywhere in this stinking world.

This is not the anthropological scrutiny one expected. This is a massacre. Are the women really like that? Maybe, but this turns out not to be the point for the moment. After pausing to complain about these women’s badly behaved children (“One such little girl told me that if I shaved my beard, I’d look like CeeLo Green. Another little girl told her mother that she didn’t like the way I smelled”), Als winds up for the finish:

These were the children of the mothers SL longed to kiss, and protect, even as my wounds would not heal and shall never heal because now I have the hatred of a white woman and if SL doesn’t think his unconditional love of them and ultimately wary love of me didn’t contribute to the immense loss of our love, he’s crazy.

Oh right—these women are sexual rivals, you suddenly remember. Als is fuming at his ex. Look at how he sacrifices, sixty pages into the essay, his measured appraisal of complex interracial relationships in order to capture the bitterness of the wounded lover. He couldn’t nail the emotional part without first going after the white girls. And he couldn’t take the risk of chasing that exact bitter note if it weren’t for the relaxed expansiveness of the essay as a whole.

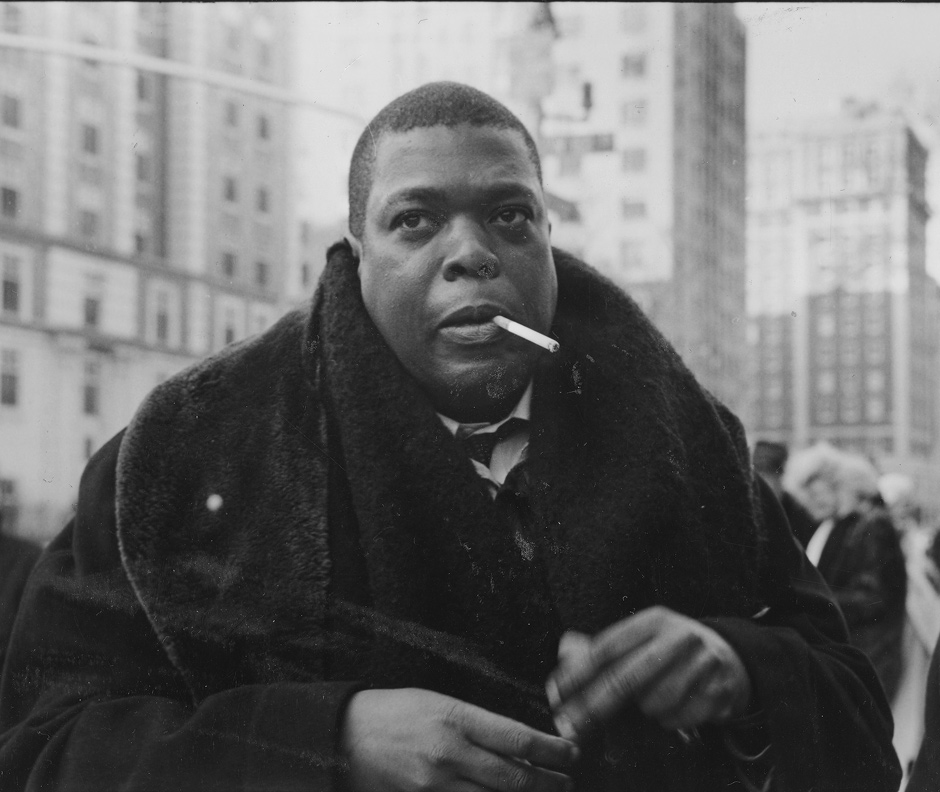

Als goes on to trace many other kinds of relations between white women and black men. In his essay on Richard Pryor, one of the best in White Girls, Als writes that Pryor, who talked much about interracial sex in his routines, “was not only an integrationist but an integrationist of white women and black men, one of the most taboo adult relationships.” Als is that kind of integrationist too, but he expands the idea of relationships beyond sexual ones to include many kinds of personal intimacies as well as artistic and intellectual influences, all of which come up in the course of his biographical sketches. And in one essay, Als touches on the source of the taboo itself.

The most destructive intimacy between black men and white women historically was not a real intimacy but a fantasy: the imagined sexual intimacy between black men and white women that became a common pretext for murdering black men. Als wrote “GWTW” (the title refers to the acronym for Gone With the Wind) to accompany a book of photos called Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America (edited by James Allen, 2000). He writes of his ambivalence about having been asked by “largely white editors” to provide a “lyrical” response to pictures of murdered black men. The essay takes him to another childhood encounter with fictional white girls. He recalls going to a revival of Gone With the Wind with his mother and brother. “We ignored the pitiful colored people in the film because we wanted to enjoy ourselves, and in Margaret Mitchell’s revisionist tale of the South, Vivien Leigh was so pretty.” Here, falling under the spell of a white female character is not benign; it means being drawn into the movie’s racist zero-sum logic:

Sitting in the movie theater, watching GWTW for the first time, I was in love with Vivien Leigh and not all those niggers, the most hateful among them being a brown-faced, oily-skinned carpetbagger who looks at our Vivien Leigh with some kind of lust and disgust. I hated him then because he intruded on the beautiful pink world.

One aspect of “white girl” influence that Als does not discuss explicitly, but that hovers over the collection, is the fact that the kind of biographical critical essays he writes became a fiefdom of white women in the Seventies and Eighties. Elizabeth Hardwick (in Seduction and Betrayal), Susan Sontag (in Under the Sign of Saturn), and Janet Malcolm (in some of the pieces recently collected in Forty-One False Starts) have been the authors of some of the best biographical criticism written in this country. They were, in those decades, among relatively few women publishing criticism. Writing in an era just before careers could be taken for granted among college-educated women, these female authors might, like Als, have had a special interest in the question of how ambition gets realized in unlikely circumstances.

The collection’s most unusual piece is “You and Whose Army?,” a monologue from the point of view of Richard Pryor’s sister. It’s not clear whether the monologue is entirely fictional or based on interviews that Als did in the course of writing Pryor’s profile. (Pryor did in fact have a sister, but it’s not clear that she had anything to do with this sketch.) The sixty-four-year-old unnamed narrator is speaking to a reporter who wants to know about the life of her famous brother. She resents his interest in Richard. Heroically self-absorbed, she dilates over the course of many pages on her own limited career as an actress and on the albatross of her brother’s celebrity. (She has read A Room of One’s Own, if you’re wondering, and doesn’t think much of Virginia Woolf’s conceit of Shakespeare’s sister.)

Pryor’s sister supports herself doing the post-production dialogue and sexual sound effects for pornography videos. It is, she insists, a form of acting:

I have appeared—if voices appear, and they do—in everything from Fags in Love, Fags on Vacation (1992) to Mystic’s Pizza (2001). You’ve felt yourself while you’ve felt me doing Polish accents. Or anal discomfort. The old gag and sputter when it comes to oral. I do it all.

She “plays” both men and women, but “there are certain tonal facts about my voice that I can’t ignore. I am a Negress. As such, I have a great deal of bass in my speech that cuts girlishness off at the pass.” Girlishness, that signature style of middle- and upper-class American white women, is unavailable to her even in her mostly disembodied line of work because of the pitch of her speaking voice.

Pryor’s sister’s “half-assed career” suggests the limits of our imaginative flights away from our actual bodies. The working actor may be released from the prison of her own personality, but the actor looking for work is trapped in the prison of a generic body. How many roles could Richard Pryor’s sister ever have gone up for, even if she’s as good as she claims? If Sarah Bernhardt could play Hamlet in her fifties, then so, in theory, might Pryor’s sister. But in fact her career has depended on how many parts get written for someone of roughly her age and sex and race, which is not very many. How much should these categories matter? Do we want more directors to cast wildly against type? Or do we think that most of our Hamlets should, in fact, be played by youngish men? The body has something to do with the character. The question is—what?

This Issue

February 6, 2014

The Whistleblowers

The Most Catastrophic War

On Breaking One’s Neck